Fig. 1.1

Anal canal

The “anatomic” or “embryologic” anal canal is only 2.0 cm long, extending from the anal verge to the dentate line, the level that corresponds to the proctodeal membrane. The “surgical” or “functional” anal canal is longer, extending for approximately 4.0 cm (in men) from the anal verge to the anorectal ring (levator ani).

The anorectal ring is at the level of the distal end of the ampullary part of the rectum and forms the anorectal angle and the beginning of a region of higher intraluminal pressure. Therefore, this definition correlates with digital, manometric, and sonographic examinations.

Anatomic Relations of the Anal Canal

Posteriorly, the anal canal is related to the coccyx and anteriorly to the perineal body and the lowest part of the posterior vaginal wall in the female and to the urethra in the male. The ischium and the ischiorectal fossa are situated on either side. The fossa ischiorectal contains fat and the inferior rectal vessels and nerves, which cross it to enter the wall of the anal canal.

Muscles of the Anal Canal

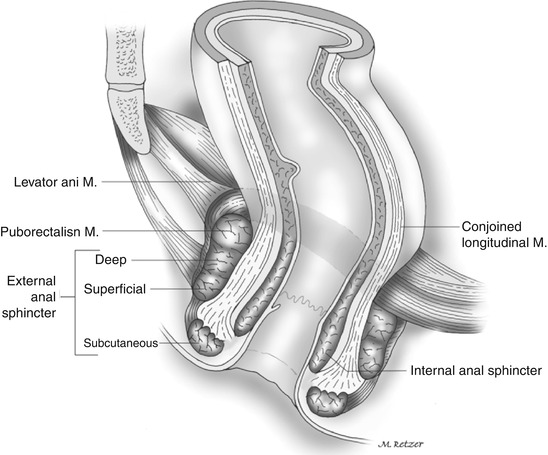

The muscular component of the mechanism of continence can be stratified into three functional groups: lateral compression from the pubococcygeus, circumferential closure from the internal and external anal sphincter, and angulation from the puborectalis (Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2

Muscles of the anal canal

Internal Anal Sphincter

The internal anal sphincter represents the distal 2.5- to 4.0-cm condensation of the circular muscle layer of the rectum. As a consequence of both intrinsic myogenic and extrinsic autonomic neurogenic properties, the internal anal sphincter is a smooth muscle in a state of continuous maximal contraction and represents a natural barrier to the involuntary loss of stool and gas.

The lower rounded edge of the internal anal sphincter can be felt on physical examination, about 1.2 cm distal to the dentate line. The groove between the internal and external anal sphincter, the intersphincteric sulcus, can be visualized or easily palpated.

Endosonographically, the internal anal sphincter is a 2- to 3-mm-thick circular band and shows a uniform hypoechogenicity.

External Anal Sphincter

The external anal sphincter is the elliptical cylinder of striated muscle that envelops the entire length of the inner tube of smooth muscle, but it ends slightly more distal than the internal anal sphincter.

The deepest part of the external anal sphincter is intimately related to the puborectalis muscle, which can actually be considered a component of both the levator ani and the external anal sphincter muscle complexes.

In the male, the upper half of the external anal sphincter is enveloped anteriorly by the conjoined longitudinal muscle, whereas the lower half is crossed by it.

In the female, the entire external anal sphincter is encapsulated by a mixture of fibers derived from both longitudinal and internal anal sphincter muscles.

The automatic continence mechanism is formed by the resting tone, maintained by the internal anal sphincter, and magnified by voluntary, reflex, and resting external anal sphincter contractile activities.

In response to conditions of threatened incontinence, such as increased intra-abdominal pressure and rectal distension, the external anal sphincter and puborectalis reflexively and voluntarily contract further to prevent fecal leakage.

The external anal sphincter and the pelvic floor muscles, unlike other skeletal muscles, which are usually inactive at rest, maintain unconscious resting electrical tone through a reflex arc at the cauda equina level.

Conjoined Longitudinal Muscle

Whereas the inner circular layer of the rectum gives rise to the internal anal sphincter, the outer longitudinal layer, at the level of the anorectal ring, mixes with fibers of the levator ani muscle to form the conjoined longitudinal muscle. This muscle descends between the internal and external anal sphincter, and ultimately some of its fibers, referred to as the corrugator cutis ani muscle, traverse the lowermost part of the external anal sphincter to insert into the perianal skin.

Possible functions of the conjoined longitudinal muscle include attaching the anorectum to the pelvis and acting as a skeleton that supports and binds the internal and external sphincter complex together.

Epithelium of the Anal Canal

The lining of the anal canal consists of an upper mucosal (endoderm) and a lower cutaneous (ectoderm) segment (Fig. 1.1).

The dentate (pectinate) line is the “saw-toothed” junction between these two distinct origins of venous and lymphatic drainage, nerve supply, and epithelial lining. Above this level, the intestine is innervated by the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, with venous, arterial, and lymphatic drainage to and from the hypogastric vessels. Distal to the dentate line, the anal canal is innervated by the somatic nervous system, with blood supply and drainage from the inferior hemorrhoidal system. These differences are important when the classification and treatment of hemorrhoids are considered.

The pectinate or dentate line corresponds to a line of anal valves that represent remnants of the proctodeal membrane. Above each valve, there is a little pocket known as an anal sinus or crypt. These crypts are connected to a variable number of glands, in average 6 (range, 3–12).

More than one gland may open into the same crypt, whereas half the crypts have no communication.

The anal gland ducts, in an outward and downward route, enter the submucosa; two-thirds enter the internal anal sphincter, and half of them terminate in the intersphincteric plane. Obstruction of these ducts, presumably by accumulation of foreign material in the crypts, may lead to perianal abscesses and fistulas.

Cephalad to the dentate line, 8–14 longitudinal folds, known as the rectal columns (columns of Morgagni), have their bases connected in pairs to each valve at the dentate line.

At the lower end of the columns are the anal papillae. The mucosa in the area of the columns consists of several layers of cuboidal cells and has a deep purple color because of the underlying internal hemorrhoidal plexus. This 0.5- to 1.0-cm strip of mucosa above the dentate line is known as the anal transition or cloacogenic zone. Cephalad to this area, the epithelium changes to a single layer of columnar cells and macroscopically acquires the characteristic pink color of the rectal mucosa.

The cutaneous part of the anal canal consists of modified squamous epithelium that is thin, smooth, pale, stretched, and devoid of hair and glands.

Rectum

Both proximal and distal limits of the rectum are controversial: the rectosigmoid junction is considered to be at the level of the third sacral vertebra by anatomists but at the sacral promontory by surgeons, and likewise the distal limit is regarded to be the muscular anorectal ring by surgeons and the dentate line by anatomists.

The rectum measures 12–15 cm in length and has three lateral curves: the upper and lower are convex to the right and the middle is convex to the left. These curves correspond intraluminally to the folds or valves of Houston. The two left-sided folds are usually noted at 7–8 cm and at 12–13 cm, respectively, and the one on the right is generally at 9–11 cm. The middle valve (Kohlrausch’s plica) is the most consistent in presence and location and corresponds to the level of the anterior peritoneal reflection.

Although the rectal valves do not contain all muscle wall layers from a clinical point of view, they are a good location for performing rectal biopsies, because they are readily accessible with minimal risk for perforation.

The rectum is characterized by its wide, easily distensible lumen and the absence of taeniae, epiploic appendices, haustra, or a well-defined mesentery.

The word “mesorectum” has gained widespread popularity among surgeons to address the perirectal areolar tissue, which is thicker posteriorly, containing terminal branches of the inferior mesenteric artery and enclosed by the fascia propria.

The “mesorectum” may be a metastatic site for a rectal cancer and is removed during surgery for rectal cancer without neurologic sequelae because no functionally significant nerves pass through it.

The upper third of the rectum is anteriorly and laterally invested by peritoneum; the middle third is covered by peritoneum on its anterior aspect only. Finally, the lower third of the rectum is entirely extraperitoneal, because the anterior peritoneal reflection occurs at 9.0–7.0 cm from the anal verge in men and at 7.5–5.0 cm from the anal verge in women.

Anatomic Relations of the Rectum

The rectum occupies the sacral concavity and ends 2–3 cm anteroinferiorly from the tip of the coccyx. At this point, it angulates backward sharply to pass through the levators and becomes the anal canal. Anteriorly, in women, the rectum is closely related to the uterine cervix and posterior vaginal wall; in men, it lies behind the bladder, vas deferens, seminal vesicles, and prostate. Posterior to the rectum lie the median sacral vessels and the roots of the sacral nerve plexus.

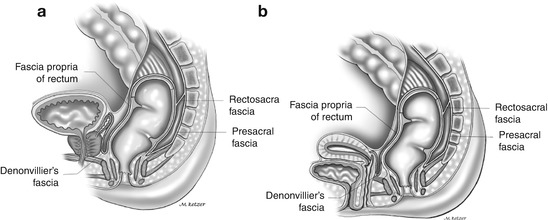

Fascial Relationships of the Rectum

The parietal endopelvic fascia lines the walls and floor of the pelvis and continues on the internal organs as a visceral pelvic fascia (Fig. 1.3a, b).

Fig. 1.3

Fascial relationships of the rectum: (a) male, (b) female

The lateral ligaments or stalks of the rectum are distal condensations of the pelvic fascia that form a roughly triangular structure with a base on the lateral pelvic wall and an apex attached to the lateral aspect of the rectum.

The lateral stalks are comprised essentially of connective tissue and nerves, and the middle rectal artery does not traverse them. Branches, however, course through in approximately 25 % of cases. Consequently, division of the lateral stalks during rectal mobilization is associated with a 25 % risk for bleeding.

One theoretical concern in ligation of the stalks is leaving behind the lateral mesorectal tissue, which may limit adequate lateral or mesorectal margins during cancer surgery.

The presacral fascia is a thickened part of the parietal endopelvic fascia that covers the concavity of the sacrum and coccyx, nerves, the middle sacral artery, and presacral veins. Operative dissection deep to the presacral fascia may cause troublesome bleeding from the underlying presacral veins.

Presacral hemorrhage occurs as frequently as 4.6–7.0 % of resections for rectal neoplasms, and despite its venous nature, can be life threatening. This is a consequence of two factors: the difficulty in securing control because of retraction of the vascular stump into the sacral foramen and the high hydrostatic pressure of the presacral venous system.

The rectosacral fascia is an anteroinferiorly directed thick fascial reflection from the presacral fascia at the S4 level to the fascia propria of the rectum just above the anorectal ring. The rectosacral fascia, classically known as the fascia of Waldeyer, is an important landmark during posterior rectal dissection.

The visceral pelvic fascia of Denonvilliers is a tough fascial investment that separates the extraperitoneal rectum anteriorly from the prostate and seminal vesicles or vagina.

Urogenital Considerations

Identification of the ureters is advisable to avoid injury to their abdominal or pelvic portions during colorectal operations. On both sides, the ureters rest on the psoas muscle in their inferomedial course; they are crossed obliquely by the spermatic vessels anteriorly and the genitofemoral nerve posteriorly. In its pelvic portion, the ureter crosses the pelvic brim in front of or a little lateral to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery and descends abruptly between the peritoneum and the internal iliac artery.

In the female, as the ureter traverses the posterior layer of the broad ligament and the parametrium close to the side of the neck of the uterus and upper part of the vagina, it is enveloped by the vesical and vaginal venous plexuses and is crossed above and lateromedially by the uterine artery.

Arterial Supply of the Rectum and Anal Canal

The superior hemorrhoidal artery is the continuation of the inferior mesenteric artery, once it crosses the left iliac vessels. The artery descends in the sigmoid mesocolon to the level of S3 and then to the posterior aspect of the rectum. In 80 % of cases, it bifurcates into right, usually wider, and left terminal branches; multiple branches are present in 17 %. These divisions, once within the submucosa of the rectum, run straight downward to supply the lower rectum and the anal canal.

The superior and inferior hemorrhoidal arteries represent the major blood supply to the anorectum. In addition, it is also supplied by the internal iliac arteries.

The contribution of the middle hemorrhoidal artery varies with the size of the superior hemorrhoidal artery; this may explain its controversial anatomy. Some authors report absence of the middle hemorrhoidal artery in 40–88 %, whereas others identify it in 94–100 % of specimens.

The middle hemorrhoidal artery is more prone to be injured during low anterior resection, when anterolateral dissection of the rectum is performed close to the pelvic floor and the prostate and seminal vesicles or upper part of the vagina are being separated.

The anorectum has a profuse intramural anastomotic network, which probably accounts for the fact that division of both superior and middle hemorrhoidal arteries does not result in necrosis of the rectum.

The paired inferior hemorrhoidal arteries are branches of the internal pudendal artery, which in turn is a branch of the internal iliac artery.

Venous Drainage and Lymphatic Drainage of the Rectum and Anal Canal

The anorectum also drains, via middle and inferior hemorrhoidal veins, to the internal iliac vein and then to the inferior vena cava.

The external hemorrhoidal plexus, situated subcutaneously around the anal canal below the dentate line, constitutes when dilated the external hemorrhoids.

The internal hemorrhoidal plexus is situated submucosally, around the upper anal canal and above the dentate line. The internal hemorrhoids originate from this plexus.

Lymph from the upper two-thirds of the rectum drains exclusively upward to the inferior mesenteric nodes and then to the para-aortic nodes.

Lymphatic drainage from the lower third of the rectum occurs not only cephalad, along the superior hemorrhoidal and inferior mesentery arteries, but also laterally, along the middle hemorrhoidal vessels to the internal iliac nodes.

In the anal canal, the dentate line is the landmark for two different systems of lymphatic drainage: above, to the inferior mesenteric and internal iliac nodes, and below, along the inferior rectal lymphatics to the superficial inguinal nodes, or less frequently along the inferior hemorrhoidal artery.

In the female, drainage at 5 cm above the anal verge in the lymphatic may also spread to the posterior vaginal wall, uterus, cervix, broad ligament, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and cul-de-sac, and at 10 cm above the anal verge, spread seems to occur only to the broad ligament and cul-de-sac.

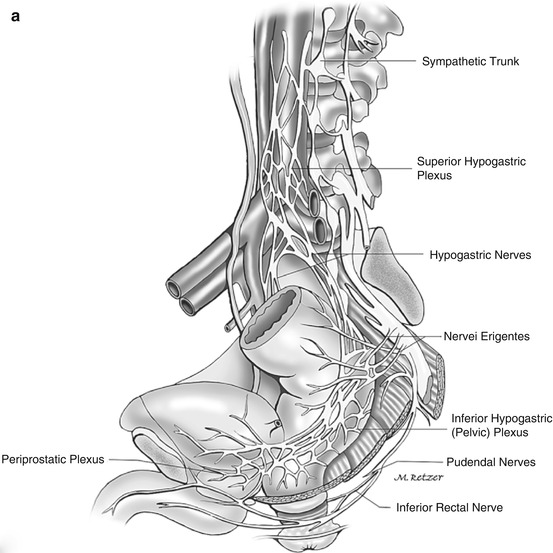

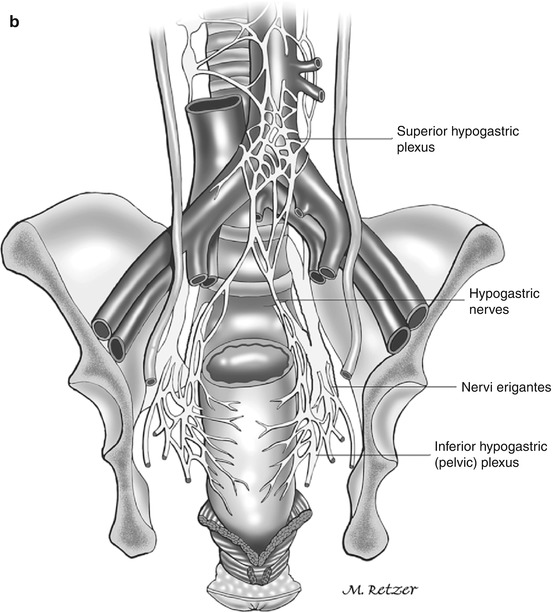

Innervation of the Rectum and Anal Canal

Innervation of the Rectum

The sympathetic supply of the rectum and the left colon arises from L1, L2, and L3 (Fig. 1.4a, b).

Fig. 1.4

(a, b) Innervation of the colon, rectum, and anal canal

Two main hypogastric nerves, on either side of the rectum, carry sympathetic innervation from the hypogastric plexus to the pelvic plexus.

The parasympathetic fibers to the rectum and anal canal emerge through the sacral foramen and are called the nervi erigentes (S2, S3, and S4).

The periprostatic plexus, a subdivision of the pelvic plexus situated on Denonvilliers’ fascia, supplies the prostate, seminal vesicles, corpora cavernosa, vas deferens, urethra, ejaculatory ducts, and bulbourethral glands.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree