Anal Fissure

Sanjay P. Jobanputra

Wisdom is nothing more than healed pain.

—ROBERT E. LEE

Anal fissure (fissure-in-ano) is a common anorectal condition, which is also one of the most painful. It can be very troubling because, if acute, the severity of patient discomfort and extent of disability far exceed that which would be expected from a seemingly trivial lesion.

An anal fissure is a cut or crack in the anal canal or anal verge that may extend from the mucocutaneous junction to the dentate line. It can be acute or chronic. It may occur at any age (it is the most common cause of rectal bleeding in infants) but is usually a condition of young adults, with both sexes being affected equally. Anal fissures are most commonly found in the posterior midline. However, in 10% of women it will be seen in the anterior midline.37 This compares with only 1% incidence in men in this location.37 Abramowitz and colleagues prospectively studied 165 consecutive women during their last 3 months of pregnancy and following delivery and noted that one-third develop thrombosed external hemorrhoids or anal fissures.3 They attributed the most important predisposing factor to that of dyschezia (difficult or painful evacuation).

▶ ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Anal fissure has been attributed to constipation or to straining at stool; theoretically, the passage of a hard fecal bolus through a relatively tight anal sphincter is thought to crack the anal canal. Patients will often remember the exact time the fissure developed based on the symptoms. Classically, this will almost always be associated with an episode of constipation. To identify risk factors for the development of an anal fissure, Jensen studied 174 patients with chronic anal fissure and compared them with controls with respect to diet, beverage consumption, occupational exposures, and medical/surgical history.47 A decreased risk was associated with increased consumption of raw fruits, vegetables, and whole grain bread. A significantly increased risk was noted with frequent consumption of white bread, sauces thickened with a roux, bacon, and sausage. Risk was not related to consumption of coffee, tea, or alcohol.

Even though usually associated with constipation, anal fissure can also be a consequence of frequent defecation and diarrhea. It may be noted with nonspecific inflammatory bowel disease and must be considered in the differential diagnosis of certain specific inflammatory conditions (e.g., syphilis, tuberculosis, gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, herpes, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS], carcinoma, and others). If there is cause for concern as to the true nature of the ulcer or fissure, biopsy, stool culture, serology, and gastrointestinal evaluation may be indicated. When anal fissure occurs in an unusual location, especially laterally, the physician must entertain the possibility that the patient harbors nonspecific inflammatory bowel disease, likely Crohn’s disease.

Why the fissure is most commonly located in the posterior anal canal is a subject of some controversy. Lockhart-Mummery believed that the explanation can be found in the structure of the external sphincter.63 The lower portion of this muscle is not truly circular but rather consists of a band of muscle fibers that pass from posterior to anterior and split around the anus. He postulated that the anal mucosa is, therefore, best supported laterally and is weakest posteriorly. The decreased anterior support in women is believed to account for the greater occurrence in this location than in men. Additional evidence reinforcing the Lockhart-Mummery concept may be apparent when the physician inserts an anal retractor too vigorously at the time of hemorrhoid surgery. The split

that may occur is almost invariably located posteriorly. Likewise, if the sphincter is stretched in the cadaver, tearing almost always occurs posteriorly.64

that may occur is almost invariably located posteriorly. Likewise, if the sphincter is stretched in the cadaver, tearing almost always occurs posteriorly.64

JOHN PERCY LOCKHART-MUMMERY (1875-1957)

|

Lockhart-Mummery was born at Islip Manor, Northolt, England, the eldest son of a distinguished dental surgeon. He was educated at Leys School and Caius College, Cambridge. He was an outstanding student and in 1897 was appointed an assistant demonstrator in anatomy at his alma mater. In 1900, he became a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons and subsequently received several hospital appointments. In 1903, having developed a special interest in proctology, he was appointed assistant surgeon at St. Mark’s Hospital. In 1904, he was Hunterian professor at the Royal College of Surgeons, and in 1909, he was Jacksonian prizewinner at the college. He contributed extensively to the literature throughout his career. Among his writings were six books on colorectal surgery, in addition to two collections of essays on nonmedical subjects. He was a very energetic man, even “hopping up the steps to the hospital”—a rather relevant observation; while a student at Cambridge, he had undergone a leg amputation for sarcoma by Lord Lister himself. He was the first secretary of the British Proctological Society and was instrumental in establishing it as an independent section of the Royal Society of Medicine. In 1937, he was elected as a fellow of the American College of Surgeons. In 1940, after 37 years at St. Mark’s Hospital, Lockhart-Mummery was made an honorary consulting surgeon. (Lockhart-Mummery P. Fissure-in-ano. In: Diseases of the Rectum and Anus: A Practical Handbook. New York, NY: William Wood; 1944:169.)

Another theory that has been suggested is related to the blood supply to the area. Klosterhalfen and associates visualized the inferior rectal artery by means of postmortem angiography, by manual preparations, and by histologic study following vascular injection.56 They determined that in 85% of specimens, the posterior commissure is less well perfused than other areas of the anal canal. Hence, ischemia may be an important etiologic factor in causing anal fissure, especially in the posterior location. The authors further suggest that the blood supply, which is already tenuous, may be further compromised by compression and contusion as the branch of the inferior rectal artery passes through the internal anal sphincter. Others have confirmed in cadaveric studies that there is a significant trend to an increasing number of arterioles from posterior to anterior in the subanodermal space at all levels.67

Schouten and colleagues assessed microvascular perfusion of the anoderm by means of Doppler flowmetry in 27 patients.104 Anodermal blood flow at the fissure site was significantly lower at the posterior commissure of the controls. Reduction of anal pressure by sphincterotomy improved anodermal blood flow, resulting in healing of the fissure. These observations lend further support to the concept that ischemia is the etiologic factor that contributes to the development of fissure disease. A later study by the same authors, this time involving 178 subjects, confirmed that anodermal blood flow was less in the posterior midline than in other segments of the anal canal.105

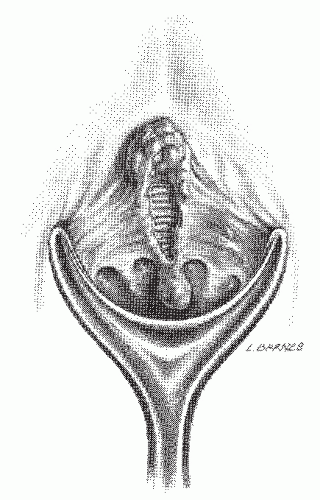

Why some fissures heal spontaneously and others become chronic is an unresolved question. Ischemia, infection, or lymphatic obstruction secondary to persistent inflammation may be responsible. A characteristic skin tag (i.e., a sentinel pile) may develop distally, whereas proximally, a hypertrophied anal papilla may be seen (Figures 12-1,12-2 and 12-3). If one wishes to attempt an anthropomorphic explanation for

the occurrence of skin tags and papillae, it is as if healing cannot take place across the defect produced by the fissure, so the body attempts to heal it through overgrowth on the proximal and distal ends of the defect. One often observes that the internal anal sphincter muscle fibers can be seen at the base of the open wound (Figures 12-1 and 12-4).

the occurrence of skin tags and papillae, it is as if healing cannot take place across the defect produced by the fissure, so the body attempts to heal it through overgrowth on the proximal and distal ends of the defect. One often observes that the internal anal sphincter muscle fibers can be seen at the base of the open wound (Figures 12-1 and 12-4).

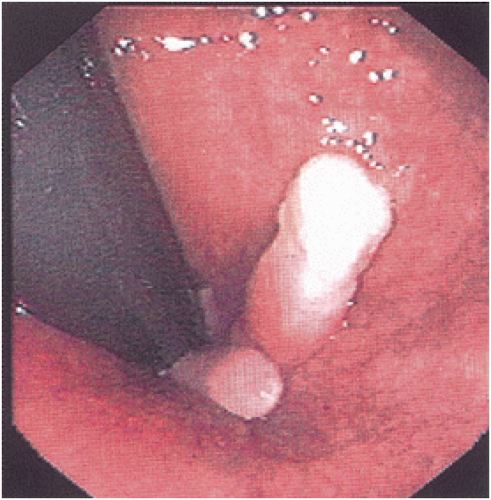

FIGURE 12-2. Prolapsed, hypertrophied anal papilla associated with anal fissure. This condition must be distinguished from an external hemorrhoid in order to provide the appropriate treatment. |

▶ PHYSIOLOGIC STUDIES

Anal manometric pressure studies in patients with anal fissure have interested investigators for some time. Duthie and Bennett in 1964 were among the earliest who measured anal canal pressures. They used an open-ended tube connected to a recording device by a strain gauge.21 Although all patients had demonstrable spasm of the sphincter based on digital examination, no increase in the resting pressure was found when they were compared with control subjects. When sphincter stretch was performed, a moderate fall in pressure was noted, but it returned virtually to normal by the eighth postoperative day. It appeared to the authors that the therapeutic effect of sphincter stretch was not related so much to reduction in anal pressure as to prevention of the spasm.21 Others have observed a similar pattern in which the pressure falls after internal anal sphincterotomy.5,14,41,105

FIGURE 12-4. Artist’s concept of chronic posterior anal fissure with skin tag and hypertrophied anal papilla. Note fibers of the internal anal sphincter at the base of the wound. |

However, Gibbons and Read employed perfusion probes of varying diameters in patients with chronic anal fissure.34 Resting pressures were elevated in all subjects when compared with controls, irrespective of probe size. They, therefore, postulated that resting pressures are indeed elevated in individuals with an anal fissure and that this observed phenomenon is not caused by spasm. They postulated that ischemia of the anal canal mucosa may be the cause of pain and the failure of fissures to heal.

Nothmann and Schuster performed balloon rectosphincteric manometry on patients with anal fissure.84 Resting pressures were twice as high as those measured in control subjects. Technique is important, however. One must recognize that resting pressures measured with an open-tipped tube in patients with anal fissure may be normal, whereas those measured by balloon catheter are usually elevated.106 Following distension of the rectum by the balloon, there is the expected internal sphincter relaxation, but this is followed by a marked and prolonged contraction above the initial baseline, termed the “overshoot” phenomenon.84 Nothmann and Schuster concluded that this reflexively stimulated sphincter spasm is involved in the etiology of the condition.84

Keck and colleagues examined manometric findings in patients with anal fissure by the use of a computer-assisted system.53 They concluded that the primary abnormality in fissure is persistent hypertonia affecting the entire internal sphincter.

One can add another possibility to the theories and observations of the ameliorative effect of sphincterotomy. Abcarian and associates, by their manometric evaluation of patients with anal fissure, concluded that the benefit is really the consequence of an anatomic widening of the anal canal that occurs during sphincterotomy.2

Roe and coworkers have described a technique for quantifying anal canal sensation by means of two platinum electrodes placed 1 cm apart and connected to copper wires passed to a constant current generator.99 Patients with acute anal fissure exhibited a lower threshold of sensation at the site of the fissure. The authors propose that the findings may reflect stimulation of exposed nerve endings at the base of the fissure rather than actual heightened sensory awareness in this group of patients. The value of this experimental modality in the diagnosis and therapy of patients with anorectal disorders, particularly incontinence, has yet to be determined.

Another potentially useful investigative study is that of anal canal ultrasonography. Reissman believes that this investigation may be important in identifying unrecognized obstetrically related sphincteric injuries before performance of internal anal sphincterotomy.95 Although it is recognized that anal ultrasound may be rather difficult to perform in the presence of an acute, painful fissure, one could consider the advisability of identifying such at-risk individuals. Ultrasound

may also be considered in patients who have had previous internal sphincterotomy and present with recurrent fissure.

may also be considered in patients who have had previous internal sphincterotomy and present with recurrent fissure.

▶ HISTOPATHOLOGY

Nothing in particular is histologically diagnostic of an anal fissure (Figure 12-5). If the lesion is excised and submitted for pathologic examination, usually typical nonspecific inflammatory changes are observed. Brown and colleagues prospectively studied 18 consecutive patients who underwent internal anal sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure and took a biopsy specimen from the base and also from the muscle before division.13 Histologic evaluation confirmed the presence of fibrosis throughout the internal sphincter, but no such finding was identified in controls.

▶ SYMPTOMS

The diagnosis of an anal fissure can usually be made based on the history alone. The characteristic complaints of a patient with an acute anal fissure are pain and bleeding. The pain usually occurs with and immediately after defecation. One usually describes the pain as severe and sharp, often stating he or she feels as if glass is cutting the person during the act of defecation. Often, the pain ceases in a few minutes, but occasionally it may persist for hours. The patient often relates that constipation is the antecedent event, but once pain develops, the fear of the act of defecation and refusal of the call to stool can exacerbate this problem. This anxiety leads to fecal impaction, particularly in children and in the elderly. Bleeding is usually minimal and frequently occurs only on the toilet paper, but sometimes blood will be seen in the toilet bowl. It is not uncommon for patients to report no evidence of bleeding.

The pain of anal fissure can be differentiated from that of proctalgia fugax (see Chapter 20) in that the latter condition produces discomfort, which is usually not related to bowel action. In addition, the patient with a fissure feels the discomfort in the anal area; the pain of proctalgia fugax is higher and more deep-seated. The other anal condition that commonly produces pain is a thrombosed hemorrhoid (see Chapter 11), but with this complaint, the patient also reports feeling a lump. This will not be present if an acute anal fissure is the cause of the pain.

Those individuals with a long-standing (i.e., chronic) anal fissure will present with a different symptom complex. They may complain of a lump representing the sentinel tag, drainage or discharge from the open wound, pruritus, or a combination of several symptoms. Bleeding may or may not be present, and pain is usually mild and frequently absent. Problems with micturition (e.g., retention, urgency, frequency) and dyspareunia occasionally accompany the symptoms of both acute and chronic fissure.

EXAMINATION

Acute Fissure

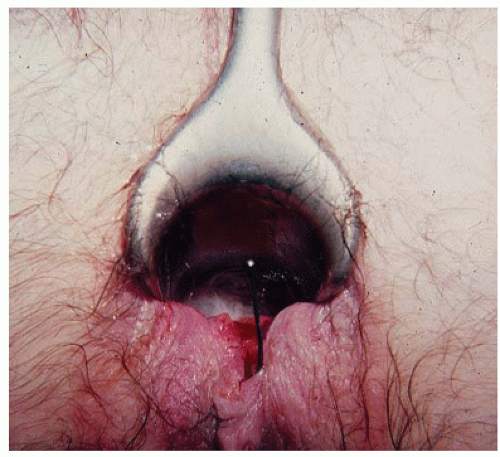

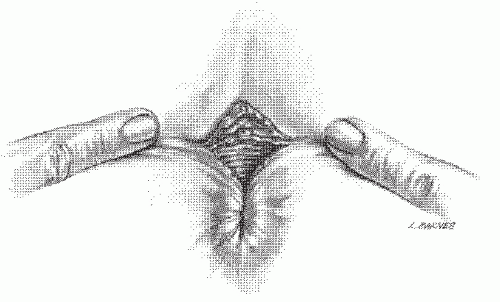

As suggested, the patient’s history is usually so characteristic that the diagnosis can be easily established. By mere inspection or gentle retraction of the perianal skin, the open wound often can be seen (Figure 12-6). If the physician is unable to pry the buttocks apart to view the area, the presence of an acute anal fissure is a virtual certainty. However, other pathologic entities such as abscess should be entertained. Under such circumstances, to attempt digital examination or to insert an instrument is usually unnecessary, counterproductive, and an inhumane exercise. Careful visual inspection of the area will often reveal the fissure, especially in the classic posterior midline. Appropriate treatment may be initiated without more specific confirmatory evidence. It is, however, important that follow-up by means of a more thorough anorectal examination when symptoms improve should be accomplished to rule out other pathologic entities, including distal anorectal carcinoma.

FIGURE 12-5. This anal fissure is an elongated defect surrounded by granulation tissue on one side and acanthotic squamous epithelium on the other. (Original magnification × 180.) |

FIGURE 12-6. Artist’s concept of a “sentinel pile,” or skin tab, at the lower edge of an anal fissure. These can easily be recognized without instrumentation. |

Examination may still be possible if the examiner is so committed and the patient is forbearing. A topical anesthetic jelly may be usefully employed. Palpation will usually demonstrate a spastic anal sphincter or a tight anal canal, and, of course, the examination will exacerbate the patient’s discomfort. The open wound is often not appreciated by the examining finger in an individual with an acute anal fissure. Because the cut is relatively superficial, there is usually no fibrosis.

Anoscopic examination, if possible, confirms the location of the fissure. The ability to perform this examination, however, may reflect the chronicity of the problem. As previously mentioned, ideally, proctosigmoidoscopic examination should be carried out prior to performing any surgical procedure to establish that the rectum, at least, is not involved by inflammatory bowel disease or any other pathologic entity. This should be a self-evident policy when an examination under anesthesia is performed. However, the clinical picture is usually so characteristic that most physicians appropriately tend to omit or defer this examination. However, if anoscopy and sigmoidoscopy are to be attempted, it is suggested that narrow-caliber instruments be used.

Chronic Fissure

There is no real agreement as to what constitutes a chronic anal fissure.90 One definition is that a fissure is chronic when it has become a clearly recognized, well-circumscribed ulcer.83 Others suggest that it is a fissure that has been present for at least 2 months. Many physicians subscribe to the rationale that is perhaps analogous to the comment made by the U.S. Supreme Court justice, Potter Stewart, when he offered his opinion with respect to a ruling on pornography. It is as follows: “… [in certain cases one is] faced with the task of trying to define what may be indefinable…. But I know it when I see it.” As with Justice Potter, surgeons seem to know it (chronic anal fissure) when they see it.

Examination of the patient with a chronic anal fissure often reveals the characteristic sentinel pile. This can at times become rather large (i.e., 3 to 4 cm). Digital examination characteristically permits palpation of the fissure, open wound, induration, and fibrosis. A hypertrophied anal papilla often can be felt at the apex of the ulcer; sometimes it may be mistaken for a tumor (Figures 12-2,12-3 and 12-4).

Because pain and tenderness are generally minimal or absent, anoscopy frequently can be accomplished without difficulty. However, scarring may result in some degree of narrowing of the anal canal, and it may be necessary to use a narrow-diameter anoscope. Characteristically, the internal anal sphincter fibers are clearly seen at the base of a chronic anal fissure. Proctosigmoidoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy should be performed to rule out the possibility of a concurrent tumor or distal inflammatory bowel disease.

Occasionally, the base of the fissure may become infected and form an abscess that may discharge as a fistula (Figure 12-7; see Chapter 14). When it occurs, the fistula is inevitably superficial—in fact, truly subcutaneous. Examination may reveal an external opening, virtually always in the midline, usually no more than 1 or 2 cm distal to the skin tag. Purulent material may be noted. A probe passed from the external opening emerges at the distal end of the fissure; usually, the internal anal sphincter is not traversed.

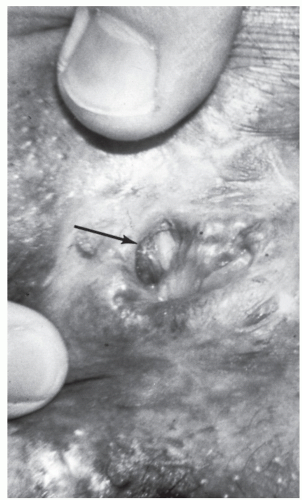

As suggested, chronic anal fissure may sometimes be associated with anal stenosis, particularly if the fissure is the result of prior anal surgery (e.g., hemorrhoidectomy

[ Figure 12-8]). Under this circumstance, treatment may require an anoplasty (see Chapter 11).

[ Figure 12-8]). Under this circumstance, treatment may require an anoplasty (see Chapter 11).

FIGURE 12-8. An anal fissure (arrow) resulting from stenosis following hemorrhoidectomy. (Courtesy of Daniel Rosenthal, MD.) |

▶ TREATMENT

Medical Management

In 2010, the Standards Practice Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons published guidelines for the management of anal fissure.89 The statement cautioned, however, that “ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure must be made by the physician in light of all the circumstances presented by the individual patient.” Those with a history suggestive of anal fissure of relatively recent onset are usually successfully treated by conservative measures, such as stool softeners (e.g., docusate sodium), bulking agents (e.g., psyllium), a high-fiber diet, increased water intake, and sitz baths. Preparations containing mineral oil are not advised because of difficulty in cleansing the area following defecation. Suppositories also are not recommended because they do not act effectively within the anal canal. Inserting any one of several proprietary creams (i.e., hydrocortisone-based creams and ointments in the area, with or without a local anesthetic) may offer some transient relief. To prevent recurrence, the patient should be encouraged to continue with the diet and bulk laxative agent, even after symptoms have resolved.

Topical anesthetic preparations (i.e., lidocaine 5% cream or ointment) that are applied just before defecation and/or afterward may offer transient relief of pain. Injection of a longacting local anesthetic may also afford temporary relief and may permit examination, but its use on an ambulatory basis is impractical. Anal dilators should not be employed (see later), and the application of silver nitrate without a local anesthetic will usually succeed in clearing the physician’s waiting room, so dramatic is the patient’s response. The task force concludes that nonoperative treatment continues to be safe, has few side effects, and should usually be the first step in therapy.

Sclerotherapy

Periodic reports have surfaced in the literature concerning the use of sclerotherapy with that of a local anesthetic. In a nonrandomized, noncontrolled study, Antebi and colleagues treated acute anal fissure by injection of Sotradecol (i.e., sodium tetradecyl sulfate) directly into the fissure.4 In 96 patients with a 1-year follow-up, 80% were free of symptoms and had no evidence of fissure. These investigators recommended the technique for those individuals who fail to respond to conservative management. However, this approach seems to have faded in both clinical practice and in the literature.

Solcoderm

Chen and coworkers reported the topical use of Solcoderm (Solco, Basel, Switzerland) in the treatment of anal fissure.15 The product has been employed for the management of a variety of skin diseases. In a controlled study involving 25 patients in each group, a statistically significantly better healing rate was shown with the drug at 1 month (84% vs. 28%) and at 1 year (84% vs. 44%).

Comment

This is another treatment method that has never gained much popularity in clinical practice and has virtually disappeared from current literature.

Hyperbaric Oxygen

On the theory that hypoxia is an important factor leading to the development of an anal fissure, Cundall and colleagues treated eight patients in whom conservative treatment, including glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) ointment (see later), had failed.20 Each patient received 15 hyperbaric treatments over 3 weeks. This consisted of 90 minutes of breathing 100% oxygen at 2.3 atmospheres. At the end of 3 months, five had healed. There were no side effects.

Comment

This approach to the medical management of a fissure has likewise disappeared from the literature, probably as a consequence of its considerable cost as well as compliance issues. Fundamentally, this treatment and others have been supplanted by the availability of other treatment options.

Glyceryl Trinitrate Ointment

The concept of a “chemical sphincterotomy” through the use of a nitric acid donor, topical nitroglycerine (GTN), has been the subject of numerous articles and considerable debate in both the medical literature and the lay press in recent years.39,46,65,66,68,71,89,114 Nitric oxide is a neurotransmitter that leads to relaxation of the internal sphincter. When applied

topically to the anal canal, GTN diffuses across the mucosa causing a reduction in internal anal sphincter pressure.71 This leads to improvement of anal blood flow with the consequence of increased likelihood for healing of the fissure.

topically to the anal canal, GTN diffuses across the mucosa causing a reduction in internal anal sphincter pressure.71 This leads to improvement of anal blood flow with the consequence of increased likelihood for healing of the fissure.

McLeod and Evans, in an article published in 2002, identified a total of nine randomized, controlled trials in which the efficacy of GTN was studied.71 Lund and Scholefield randomized 80 consecutive patients to receive treatments with topical 0.2% GTN ointment or a placebo.68 After 8 weeks, healing was observed in 26 of 38 patients treated with GTN (68%) but in only 3 of 39 treated with the placebo (8%). These differences were highly significant. The authors concluded that topical GTN provides rapid, sustained relief of pain in individuals with anal fissure. A multi-institutional investigation was conducted in 17 centers with the aim of determining the optimal dosage and dosing interval for the use of GTN.6 There were no significant differences observed in fissure healing among any of the treatment groups, but those who received 0.4% (1.5 mg) GTN ointment had a statistically significant decrease in pain intensity. The primary side effect was headache. Pitt and colleagues treated 1,998 patients with 0.2% GTN ointment.91 They found that the presence of a sentinel pile adversely affected the outcome. To put it another way, the longer the fissure is present, the less likely GTN will be helpful. In a systematic review by Poh et al., healing rates for GTN range from 40.4% to 68%, with the most common concentration used being 0.2%.92 Reported recurrence rates were 7.9% to 50%, with the most common complication being headaches. The frequency of this complication ranged from 5.9% to 56.4%. As would be expected, incontinence was not a significant issue in the reviewed studies.

Emami and coworkers applied a 0.2% GTN suppository for the management/healing of chronic anal fissure.25 However, the long-term results were not statistically different.

Karanlik and associates used GTN following hemorrhoidectomy in a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.52 They observed that GTN ointment significantly decreased postoperative pain following this procedure as well as reducing analgesic requirements in the immediate postoperative period. The use of the ointment also appeared to achieve more rapid wound healing. The aforementioned Standards Practice Task Force opined that anal fissures may be treated with topical nitrates, although nitrates are (only) marginally superior to placebo with respect to healing.

Calcium Channel Blockers

Calcium ions are important for smooth muscle contraction. It has, therefore, been suggested that calcium channel blockers may be an effective treatment for anal fissure. This represents a second method for relaxing the internal anal sphincter.

Nifedipine and diltiazem have been shown to be effective calcium channel antagonists. Cook and coworkers undertook a study with oral nifedipine in healthy volunteers and in 15 patients with chronic anal fissure.18 A highly significant decrease in maximum resting pressure was observed along with a reduction in pain scores. Nine patients experienced complete healing after 8 weeks. Side effects included flushing and mild headache. Perotti and colleagues employed topical nifedipine (0.3%) with lidocaine ointment (1.5%) every 12 hours for 6 weeks in a prospective, randomized, doubleblind study.88 The control group received topical lidocaine ointment (1.5%) with hydrocortisone acetate (1%). They found a 94.5% incidence of healing in the nifedipine group but only 16.4% of the controls had healed. A total of 110 patients with chronic anal fissure were entered into the trial.88

Diltiazem (DTZ) is another calcium channel blocker that has been proffered as an alternative for the treatment of chronic anal fissure. In a prospective assessment of 71 such patients, Knight and coworkers found a rate of healing of 75%.57 They concluded that topical 2% DTZ has a high success rate. Jonas and colleagues employed DTZ in patients in whom GTN had failed.49 Thirty-nine individuals were treated, with 49% healing within 8 weeks. Side effects included headache, drowsiness, mood swings, and perianal itching. The same group compared oral versus topical DTZ and noted that the topical application is more effective and is associated with fewer side effects.48 Kocher and associates performed a randomized trial in which the side effects of GTN were compared with those of DTZ.58 These investigators found no difference in healing rates, but because of much fewer side effects associated with DTZ (especially headache), they opined that DTZ “may be the preferred firstline treatment for chronic anal fissure.”58

Despite the similar rates of healing between GTN and calcium channel blockers, Jonas and associates found 2% diltiazem ointment to be an effective treatment in patients who failed GTN treatment.49 They found 44% healing in this group. The Standards Practice Task Force felt that anal fissures may be treated with topical calcium channel blockers, with (the expectation of) a lower incidence of adverse effects than topical nitrates. However, there are insufficient data to conclude whether they are superior to placebo in healing anal fissures.89

Botulinum Toxin

In 1993, Jost and Schimrigk, in a letter to the editor, originally reported the injection of botulinum toxin (BNT) into the anal sphincter as a new mode of treatment for anal fissure.50 In a subsequent report involving 12 patients, two doses (each consisting of 0.1 mL of diluted toxin corresponding to 2.5 E BoTox; BoTox Allergan, Irvine, CA) were injected into the external anal sphincter on both sides lateral to the fissure.51 Maria and coworkers conducted a double-blind, placebocontrolled study in 30 patients, with the use of saline injections for the control group.69 They used 20 U of botulinum A for the treatment group. After 2 months, 11 individuals in the treated group had healed, whereas only 2 in the control group were healed (P = .003).

BNT is a powerful poison that inhibits neuromuscular transmission. While acting through a different mechanism than GTN, its beneficial effect should be to increase blood flow to the area. Some have warned that this drug needs greater regulation, with a careful review of the risks and benefits.12 Although not common, side effects of its various applications have included increased urinary residual volume, heart block, skin and allergic reactions, muscle weakness, postural hypotension, and changes in heart rate and blood pressure.12 A case of Fournier’s gangrene has been reported after an injection of BNT.117 Transient incontinence for flatus is not unusual.

Lindsey and colleagues employed BNT in a highconcentration, low-volume solution in the treatment of patients in whom GTN therapy had failed.62 Two milliliters of 0.9% saline were injected into a 100-U vial of BNT, and a 0.4-mL aliquot was drawn into a 1-mL syringe. With the use of a 27-gauge needle, a solution of 0.2 mL was injected into the internal sphincter on either side but at some distance from the fissure.62 With this “second-line therapy,” approximately one-half of the

fissures healed. The authors concluded as follows: “A policy of first line GTN and second line BNT… avoids surgical sphincterotomy and its risks in the short term [italics mine] in almost 90 percent of cases.”62 Others have concluded that although GTN and BNT have negligible side effects, the success rates are no better than 80% initially, dropping to 55% with longer term follow-up.3 Samim et al. performed a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial in which BNT had a higher healing rate than that of topical diltiazem in the short term.103 However, at 3 months, both groups were found to have equal rates of healing, and there were also no significant differences in pain reduction in either group. They concluded that there was not a significant advantage of one treatment over the other. In the systematic review by Poh et al., the healing rates with BNT in the literature range from 27% to 96%, with most studies reporting dosing between 20 and 25 U.92 A systematic review by Yiannakopoulou concluded that BNT should be considered a treatment option for anal fissure.117 However, he further stated that “well designed randomized trials are needed for the valid estimation of the efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin in this therapeutic indication.”117

fissures healed. The authors concluded as follows: “A policy of first line GTN and second line BNT… avoids surgical sphincterotomy and its risks in the short term [italics mine] in almost 90 percent of cases.”62 Others have concluded that although GTN and BNT have negligible side effects, the success rates are no better than 80% initially, dropping to 55% with longer term follow-up.3 Samim et al. performed a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial in which BNT had a higher healing rate than that of topical diltiazem in the short term.103 However, at 3 months, both groups were found to have equal rates of healing, and there were also no significant differences in pain reduction in either group. They concluded that there was not a significant advantage of one treatment over the other. In the systematic review by Poh et al., the healing rates with BNT in the literature range from 27% to 96%, with most studies reporting dosing between 20 and 25 U.92 A systematic review by Yiannakopoulou concluded that BNT should be considered a treatment option for anal fissure.117 However, he further stated that “well designed randomized trials are needed for the valid estimation of the efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin in this therapeutic indication.”117

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree