Fig. 20.1

(a, b) Terminology for location of anal and perianal lesions. Tumors A, B, and C represent ANAL lesions that are not visible or are incompletely visible while gentle traction is placed on the buttocks. Tumor D is a perianal tumor because it is completely visible with gentle traction on the buttocks and lesion E is a skin cancer

Anal canal lesions are lesions that cannot be visualized at all, or are incompletely visualized, with gentle traction placed on the buttocks.

Perianal lesions are completely visible and fall within a 5 cm radius of the anal opening when gentle traction is placed on the buttocks.

Skin lesions fall outside of the 5 cm radius of the anal opening.

A key component of this classification system is that all clinicians, including gastroenterologists, surgeons, nurse practitioners, and medical and radiation oncologists, can perform this simple exam in their offices without the aid of an anoscope or a clear understanding of the anatomic landmarks (dentate line and anal verge) of the region.

Identification of a new zone, the transformation zone, was also proposed to help clinicians and pathologists understand how anal squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) may be found 6, 8, or even 10 cm proximal to the dentate line in the anatomic rectum.

The transition zone is a well-known region. It is an area, 0–12 mm in length beginning at the dentate line, where a “transitional urothelium-like” epithelium may be found in the rectal mucosa instead of the standard columnar mucosa of the rectum.

The transformation zone of the rectum is a region in which squamous metaplasia may be found overlying the normal columnar mucosa. This immature metaplastic tissue may extend up to the rectum in a fluid and dynamic fashion involving at times 10 cm or more of distal rectal mucosa.

The transformation zone is an important region, where metaplastic tissue susceptible to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, in particular HPV 16, may be found.

Terminology

The terminology used by pathologists when reporting premalignant lesions of the anus and perineum is often confusing to the treating clinicians.

The terms squamous cell carcinoma in situ (CIS), anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN), anal dysplasia, squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL), and Bowen’s disease may all be used to refer to the same histopathology.

AIN (a cytologic diagnosis) and dysplasia have both historically been broken into AIN I, II, and III and low-, moderate-, and high-grade dysplasia. However, as with other pathological staging systems, the intra- and interobserver variability is too high with this many categories. Therefore, when referring to anal canal, perianal, and skin lesions of the buttock, the tissue should be classified histologically, as either normal, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), or invasive cancer as is done in the AJCC Staging Manual.

Lymphatic Drainage

Lymphatic drainage above the dentate line occurs via the superior rectal lymphatics to the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes and laterally to the internal iliac nodes. Below the dentate line, drainage is primarily to the inguinal nodes but may also involve the inferior or superior rectal lymph nodes.

Etiology and Pathogenesis of Anal Dysplasia and Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The HPV is a necessary but not sufficient cause for the development of anal SCC and SIL. HPV is a DNA papovavirus with an 8 kb genome and is the most common viral sexually transmitted infection.

Although most patients clear the virus with only 1 % of the patients developing genital warts with low oncogenic potential (HPV serotypes 6 and 11), an estimated 10–46 % of patients develop subclinical infections that may harbor malignant potential (HPV serotypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 35).

Transmission is not prevented by condoms as the virus pools at the base of the penis and scrotum. Thus, abstinence is the only effective means of prevention. In women, the virus may pool and extend from the vagina to the anus.

Anoreceptive intercourse may be associated with the development of intra-anal disease, but the presence of condylomata or dysplasia within the anus does not indicate that anoreceptive intercourse has occurred.

Fortunately, the angiogenic changes associated with the development of anal HSIL are also visible with the aid of acetic acid and Lugol’s solution in the perianal skin, anus, and distal rectum through an operative microscope, colposcope, or loupes in the office or operating room (Fig. 20.2a–d). Targeted destruction is safe and may result in the same decrease in anal cancer incidence as was seen with cervical cancer when cervical Pap smears and targeted destruction were introduced for cervical disease.

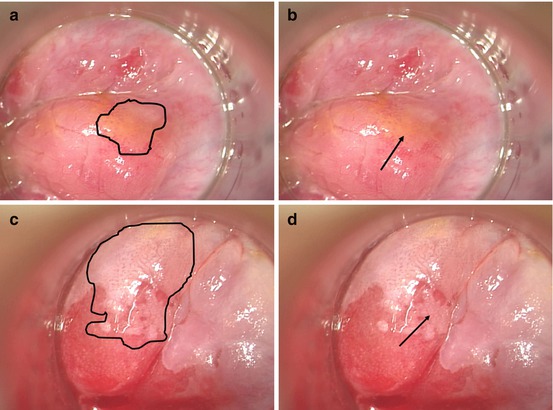

Fig. 20.2

LSIL and HSIL visualized in the office with a colposcope after the application of acetic acid. The arrows in both images depict where the biopsy of the lesion was taken. (a, b) Anal LSIL in the distal rectal mucosa with subtle punctate vessel changes. The geography of the lesion in highlighted in the left frame. (c, d) Anal HSIL in the distal rectal mucosa with the left image highlighting serpiginous, cerebriform vessels and the outline of the entire lesion and the right image highlighting the mosaic pattern created by the vessels in the acetowhite background

The cost-effectiveness of anal cytology screening system to prevent anal cancer has been demonstrated using an economic model in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM).

These studies demonstrated that screening to identify patients with HSIL to be referred for treatment would be cost-effective if performed annually for HIV-positive MSM and every 2–3 years for HIV-negative MSM.

Although the association of MSM and anal cancer is clear, the association of HIV with the development and progression of anal cancer has been hard to separate from other confounding factors. Initial studies accumulating anal cancer rates from the pre-HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) era failed to show a correlation presumably because patients succumbed to complications of the HIV.

HPV is an indolent infection that leads to cancer in a minority of patients who generally suffer from a long-term infection. Thus, as might be expected, more recent studies reporting anal cancer rates in patients who are now surviving longer with effective HAART suggest an association with HIV and anal cancer. Supporting this association is the observed rise in anal cancer and dysplasia rates seen in HIV-positive MSM and HIV-positive heterosexual men and women who do not report anoreceptive intercourse.

Further, HIV-positive patients are more likely to have HSIL and are more likely to progress from LSIL to HSIL over a 2-year time period, and both of these findings are increased in the patients with a lower CD4 count (<200 cells/mm).

Low CD4 counts are a surrogate measure for immunosuppression from the HIV infection, and it is therefore suggested that HIV infection is associated with an increased risk of progression of anal disease.

Data is accumulating that suggests that as men and women live longer in the HAART era, the indolent HPV infection results in an increased risk for the development of anal cancer, and this effect is the most significant in the most immunocompromised patients.

Epidemiology

The incidence of anal SCC has been increasing in frequency in over the last 30 years in the United States, Europe, and South America.

Anal Canal and Perianal High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions (Formerly Bowen’s Disease)

The distinction between Bowen’s disease and HSIL is unclear and appears to have more to do with the pathologist’s training and histopathologic versus cytopathologic terminology, than any biologic difference.

Bowen’s disease is anal SCC in situ, AIN II and III, and HSIL.

The term Bowen’s disease is applied to SCC in situ in both keratinizing and nonkeratinizing tissues. Thus, we feel the term is archaic and confusing, and should be abandoned in favor of HSIL. Throughout this chapter, we use the term HSIL to refer to what has previously been termed Bowen’s disease.

HSIL is commonly found as an incidental histologic finding after surgery for an unrelated problem, often hemorrhoids. The lesion is clinically unapparent, but histologic assessment of the specimen reveals HSIL (Fig. 20.3). Alternatively, patients may present with complaints of perianal burning, pruritus, or pain. Physical examination may reveal scaly, discrete, erythematous, or pigmented lesions (Fig. 20.4).

Fig. 20.3

Perianal HSIL (With permission from Beck DE, Wexner SD. Anal neoplasms. In: Beck DE, Wexner SD, editors. Fundamentals of anorectal surgery. London: W.B. Saunders; 1998. p. 261–277)

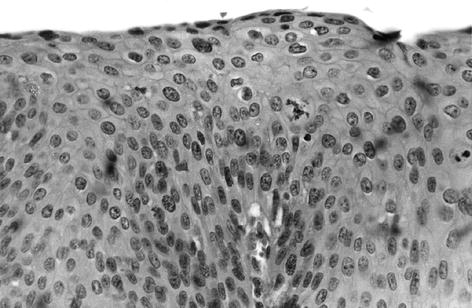

Fig. 20.4

Perianal HSIL (Photomicrograph hematoxylin and eosin ×400) (With permission from Beck DE, Wexner SD. Anal neoplasms. In: Beck DE, Wexner SD, editors. Fundamentals of anorectal surgery. London: W. B. Saunders; 1998. p. 261–277)

The natural history of HSIL is poorly defined.

In the immunocompetent, fewer than 10 % progress to cancer.

However, in immunocompromised patients, the progression rate appears greater as evidenced by the higher rates of anal cancers observed in the HIV (+) and immunosuppressed transplant patients.

As we are as yet unable to identify those patients that progress, the authors favor treatment of HSIL.

An exception to this recommendation would be patients with advanced AIDS with poor performance statuses despite maximal medical therapy. The other exception might be the elderly patient with an asymptomatic lesion and a short life expectancy.

The preferred treatment is controversial and should be tailored to the given patient. An older recommendation for the unsuspected lesion found after hemorrhoidectomy is to return the patient to the operating room for random biopsies taken at 1 cm intervals starting at the dentate line and around the anus in a clocklike fashion.

Frozen sections establish the presence of HSIL and these areas are widely locally excised with 1 cm margins. Large defects are covered with flaps of gluteal and perianal skin. Although this technique has been shown to provide excellent local control, it does not prevent recurrences. Recurrence rates in one series were as high as 23 % despite this radical approach. Although no cancers developed in this group, HIV status was not noted and complications, including incontinence, stenosis, and sexual function, were not reported. In another study of wide local excision, the authors noted a 63 % persistence rate at 1 year and a 13 % recurrence rate at 3 years. Eleven percent of the patients developed incontinence or stenosis. The unknown risk of disease progression, high recurrence rate, and the significant morbidity associated with extensive wide excisions have led many authorities (including the authors and a few editors) to rarely use or recommend this option.

A less radical approach involves taking patients to the operating room to perform high resolution anoscopy (HRA) with the aid of an operating microscope, acetic acid, and Lugol’s solution. The lesions are visualized and targeted for electrocautery destruction. Like cervical disease, the HSIL is visible because of its characteristic vascular pattern identifying the at-risk tissue for selective destruction (Fig. 20.2). This technique minimizes the morbidity of the procedure and saves the normal anal mucosa and perianal skin that would otherwise be sacrificed. Postoperative pain is significant as with any perianal procedure. HSIL identified with HRA may also simply be locally excised taking care to stay close to the lesion margin directly visualized with the operative microscope. The deep margin is kept equally close as wide local excision seems of limited benefit and increases morbidity. The resulting minimal defects heal in secondarily. High-risk patients, the immunocompromised, and patients practicing anoreceptive intercourse should be followed with Pap smears at yearly and 3 yearly intervals for the immunocompromised and immunocompetent, respectively.

Other therapeutic modalities include topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream, imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, radiation therapy, laser therapy, and combinations of the above. The reports are generally small series with limited follow-up, but there may be anecdotal success with each approach, and the options may be kept in mind for challenging cases.

Perianal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Formerly Anal Margin)

SCC arises from both the perianal skin and the anal canal.

The distinction between the two locations has become more important as they are increasingly considered different entities with separate treatments and prognosis. Immunohistochemical studies of squamous cell tumors from the anal margin and anal canal demonstrate differences in expression of cadherin, cytokeratins, and p53 confirming that these tumors are of distinct histogenetic origin.

Perianal lesions are completely visible and fall within a 5 cm radius of the anal opening when gentle traction is placed on the buttocks.

Clinical Characteristics

Perianal tumors resemble SCC of other areas of skin and are therefore staged and often treated in a similar fashion.

They have rolled, everted edges with central ulceration, and may have a palpable component in the subcutaneous tissues although the sphincter complex is not usually involved.

Patients present in the seventh decade of life with equal incidence in men and women.

Presenting symptoms include a painful lump, bleeding, pruritus, tenesmus, discharge, or even fecal incontinence. In general, perianal tumors are characterized by a delay in diagnosis due to their location and indistinct features, and SCC is no exception.

Staging

The staging of perianal SCC is based on the size of the tumor and lymph node involvement, both of which correlate with prognosis.

Lymphatic drainage of the perianal skin extends to the femoral and inguinal nodes and then to the external and common iliac nodes. Venous drainage occurs through the inferior rectal vein. Lymph node involvement is associated with the size and differentiation of the tumor.

Distant visceral metastasis at presentation is rare but should be evaluated with a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis to assess for liver metastases, as well as the presence of nodal disease. A chest X-ray or CT may be performed to evaluate for lung metastases. These tumors are generally slow growing and histologically are well differentiated with well-developed patterns of keratinization. The AJCC staging system is described in Table 20.1.

Table 20.1

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

Primary tumor (T)

Tx

Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0

No evidence of primary tumor

Tis

Carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), anal intraepithelial neoplasia II–III (AIN II–III)

T1

Tumor ≤2 cm in greatest dimension

T2

Tumor 2–5 cm in greatest dimension

T3

Tumor ≥5 cm in greatest dimension

T4

Tumor of any size invades adjacent organ(s), e.g., vagina, urethra, bladdera

Nodal status (N)

Nx

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

N0

No regional lymph node metastasis

N1

Metastasis in perirectal lymph node(s)

N2

Metastasis in unilateral internal iliac and/or inguinal lymph node(s)

N3

Metastasis in perirectal and inguinal lymph nodes and/or bilateral internal iliac and/or inguinal lymph nodes

Distant metastasis (M)

M0

No distant metastasis

M1

Distant metastasis present

Stage grouping

Stage 0

Tis

N0

M0

Stage I

T1

N0

M0

Stage II

T2,3

N0

M0

Stage IIIA

T1,2,3

N1

M0

Or T4 N0 M0

Stage IIIB

Any T

N2,3

M0

Or T4 N1 M0

Stage IV

Any T

Any N

M1

Treatment Options

Treatment of perianal SCC traditionally consisted of surgical resection with wide local excision for smaller-sized tumors and abdominoperineal resection (APR) for larger, invasive tumors.

However, it is well documented that wide local excision alone results in high locoregional recurrence rates (18–63 %) (Table 20.2) and should be reserved for those lesions that can be excised with a 1 cm margin, are Tis or T1, and do not involve enough sphincter to compromise function. A series of 27 patients with Tis and T1 lesions treated with wide local excision had a 100 % 5-year survival, and in another study, all patients with small or superficial tumors locally excised had a survival of 100 %, whereas those with deep invasion did not survive 5 years.

Table 20.2

Results of local excision of perianal tumors

Author

Year

N

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access