Anal Canal

6.1 Papillary endothelial hyperplasia in hemorrhoidal vessels vs. Angiosarcoma

6.2 Condyloma lata vs. Squamous cell carcinoma

6.3 Condyloma vs. Fibroepithelial polyp (anal tag)

6.4 Stromal changes in fibroepithelial polyp vs. Sarcoma

6.5 Reactive squamous changes vs. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia

6.7 Sexually transmitted proctitis vs. Inflammatory bowel disease involving the anus

6.8 Hidradenoma papilliferum vs. Adenocarcinoma, especially of female genital tract

6.9 Squamous cell carcinoma vs. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia

6.10 Squamous cell carcinoma vs. Skin appendage tumors

6.11 Paget disease vs. Pagetoid extension of colorectal carcinoma

6.12 Anal duct carcinoma vs. Spread of tumors from other sites

6.1 Papillary endothelial hyperplasia in hemorrhoidal vessels vs. Angiosarcoma

| Papillary Endothelial Hyperplasia in Hemorrhoidal Vessels | Angiosarcoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Any age but usually in adults in hemorrhoids. No gender predominance | Adults; male predominance |

| Location | In large hemorrhoidal vessels that have thrombosed. Sometimes, radiation treatment prompts this response in patients with rectal, gynecologic, or prostate cancers | Very rare in the anal canal and in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract in general—most cases reported have been associated with the small bowel and are deep lesions that extend into the GI tract. These tend to be epithelioid |

| Symptoms | Anal pain | For the rare anal area examples, a mass is usually detected but in general angiosarcomas of the gastrointestinal tract affect the small bowel and present with symptoms of obstruction |

| Signs | Cherry-like mass in anal canal | Nonspecific and related to the site of the mass |

| Etiology | Papillary endothelial hyperplasia is an exaggerated form of organization in thrombi | Some cases associated with ionizing radiation and some with various toxins (polyvinyl chloride, arsenic compounds, thorium compounds), but these tend to be in the liver |

| Histology | ||

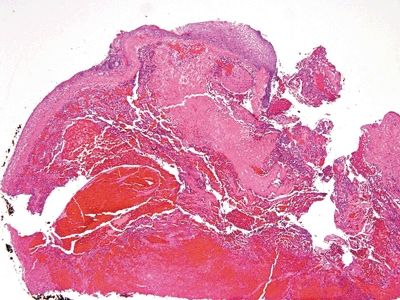

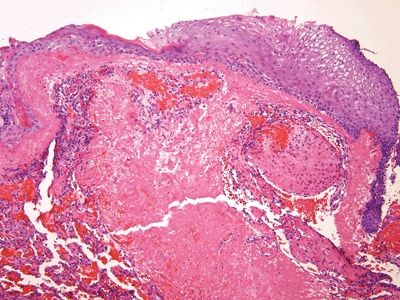

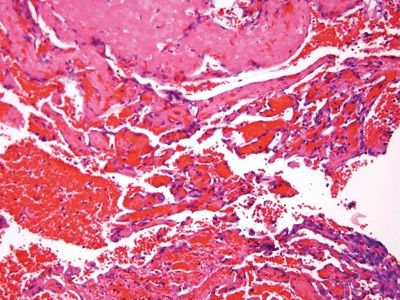

| 1. Enlarged vessels containing thrombi (Fig. 6.1.1) 2. Areas of endothelial cells coating fibrin cores in a monolayer (Figs. 6.1.2–6.1.4) 3. In radiated patients, the presence of abundant fibrinoid change of the stroma is a clue that the changes are radiation induced rather than neoplastic (Fig. 6.1.5) | 1. Overtly malignant proliferation with variable vasoformation (Fig. 6.1.6) 2. Can be solid sheets of cells and areas of epithelioid features (Figs. 6.1.7–6.1.9) 3. Multilayered endothelial cells (Fig. 6.1.10) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Removal of the hemorrhoids if they are symptomatic or interfering with personal hygiene | Surgery and sometimes chemotherapy |

| Prognosis | Benign process | Generally poor. Some low-grade lesions can be treated with good outcome |

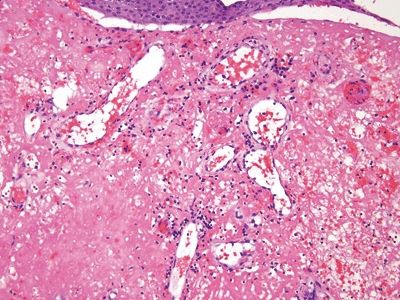

Figure 6.1.1 Papillary endothelial hyperplasia. This lesion arose in a hemorrhoidal area in a patient who had undergone radiation treatment for cervical squamous carcinoma. There is hemorrhage and amorphous debris.

Figure 6.1.2 Papillary endothelial hyperplasia. There is abundant fibrin deposition.

Figure 6.1.3 Papillary endothelial hyperplasia. There are cores of fibrin coated by a monolayer of endothelial cells.

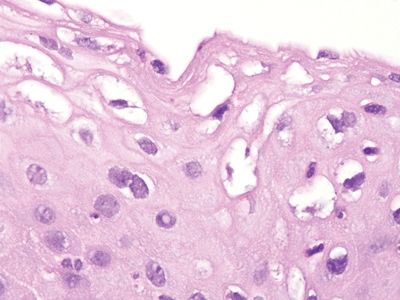

Figure 6.1.4 Papillary endothelial hyperplasia. At high magnification, the endothelial cells are not large. Compare them to the lymphocyte at the upper right.

Figure 6.1.5 Papillary endothelial hyperplasia. The amorphous fibrin debris in this field probably reflects prior radiation treatment.

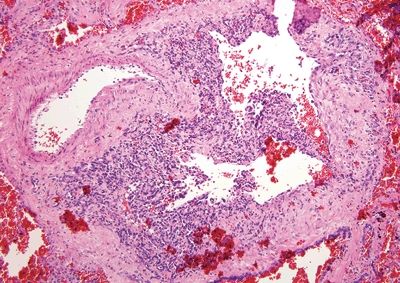

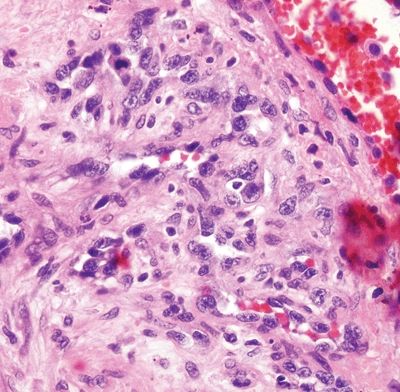

Figure 6.1.6 Angiosarcoma. This is a solid proliferation of atypical cells.

Figure 6.1.7 Angiosarcoma. There is some vasoformation, but the nuclei are enlarged compared to the adipocyte nuclei in the field.

Figure 6.1.8 Angiosarcoma. This example extends along a preexisting vessel. The malignant cells are hyperchromatic.

Figure 6.1.9 Angiosarcoma. Note the hyperchromatic nuclei.

Figure 6.1.10 Angiosarcoma. The nuclei form a monolayer on the right but are “piled up” on the left.

6.2 Condyloma lata vs. Squamous cell carcinoma

| Condyloma Lata | Squamous Cell Carcinoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Adults. A male predominance reflects the proclivity for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected persons to also harbor syphilis | Male predominance, usually middle-aged males |

| Location | Anorectum and genital region | Anal canal or perianal area |

| Symptoms | Mass, anal discharge, anal pain | Mass effect, anal pain, pain while defecating, local hemorrhage |

| Signs | Mass, friable hemorrhagic mucosa or perianal skin. Ulcers | Mass lesion |

| Etiology | Infection with Treponema pallidum | Most cases associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) |

| Histology | ||

| 1. Rich lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with striking pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Fig. 6.2.1) 2. Mild squamous atypia (Fig. 6.2.2) | 1. Marked squamous atypia with desmoplastic response but limited inflammation (Figs. 6.2.4–6.2.6) 2. Abnormal keratinization 3. Adjoining squamous mucosa may show HPV-related changes | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Antibiotics | Chemoradiation |

| Prognosis | Excellent with treatment. Masses and ulcers disappear with treatment, but the underlying HIV must still be managed | Overall good and stage dependent. Patients tend to present early with low-stage lesions because of early symptoms. Remember that anal lesions are staged by size rather than depth of invasion |

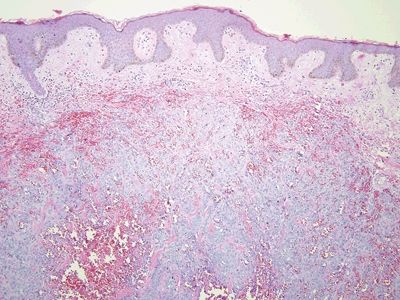

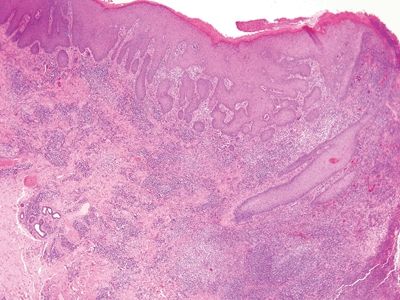

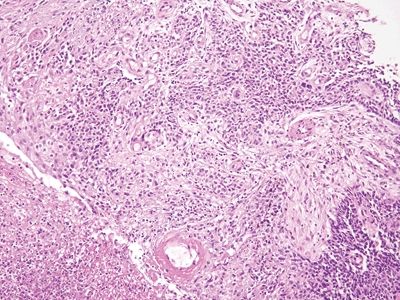

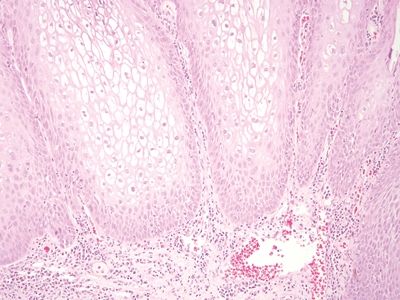

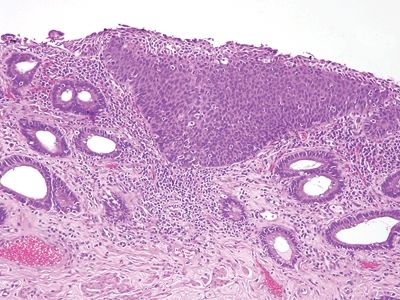

Figure 6.2.1 Condyloma lata. The eye-catching feature in this image is the dense chronic inflammation. Even at this magnification, it appears lymphoplasmacytic. There is pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia at the right.

Figure 6.2.2 The squamous epithelium appears reparative, and intercellular bridges can be seen in the basal layer.

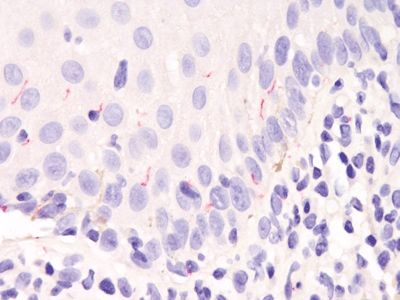

Figure 6.2.3 Condyloma lata. This is an immunostain for treponemal organisms. It is fairly specific (it also reacts with the organisms responsible for intestinal spirochetosis) but not terribly sensitive. As such, patients should be tested serologically, and the immunostain is not necessary.

Figure 6.2.4 Squamous cell carcinoma. There is ulceration but little chronic inflammation. There is desmoplasia in this field.

Figure 6.2.5 Squamous cell carcinoma. There is no in situ component in this example, but it shows necrosis. There is minimal chronic inflammation.

Figure 6.2.6 Squamous cell carcinoma. This basaloid example has invaded through the muscularis mucosae. There is some colorectal-type mucosa at the left. Many squamous cell carcinomas of the anal region arise at the junction of the squamous and columnar mucosa.

6.3 Condyloma vs. Fibroepithelial polyp (anal tag)

| Condyloma | Fibroepithelial Polyp (anal tag) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Adults/male predominance | Typically adults, no gender predilection |

| Location | Anal canal and perianal skin | At the junction between the anal canal and the skin |

| Symptoms | Patients note exophytic lesion or lesions. May interfere with hygiene | Patient notes small masses. Removal is suggested when they interfere with hygiene since removal is painful |

| Signs | Cauliflower-like lesions | May be local hemorrhage |

| Etiology | Human papillomavirus (HPV) | May be related to mucosal prolapse, constipation, and anal fissures. More common in obese patients and persons with Crohn disease |

| Histology | ||

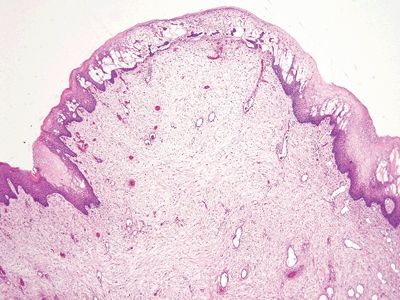

| 1. Exophytic polypoid lesions with proliferation of the epithelium with atypical nuclei restricted to the bottom half of the epithelium (Fig. 6.3.1) 2. Koilocytic atypia in nuclei (Fig. 6.3.2) 3. Minimal stromal proliferation (Fig. 6.3.3) | 1. The subepithelial layer shows prominent proliferation and mild inflammation, but the overlying squamous epithelium forms a monolayer (Fig. 6.3.4) 2. Generally, the squamous epithelium appears reactive (Fig. 6.3.5) 3. Of course, these polyps should be examined carefully as they occasionally display flat intraepithelial neoplasia (Fig. 6.3.6) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Excisional biopsy, cryotherapy, chemical ablation | Removal if they interfere with hygiene or are embarrassing to the patient |

| Prognosis | Overall good. Only a small minority progress to squamous cell carcinoma | Excellent |

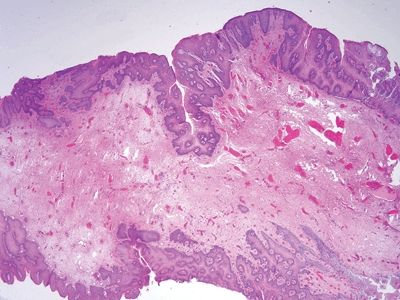

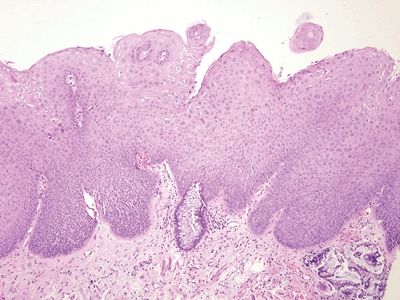

Figure 6.3.1 Condyloma. Note that most of the lesion is composed of epithelium rather than stroma. The epithelium is quite thick.

Figure 6.3.2 Condyloma. This image shows enlarged nuclei and koilocytic atypia in which there is a large perinuclear halo around many nuclei. Condyloma acuminatum is equivalent to anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN1/low-grade AIN/mild dysplasia).

Figure 6.3.3 Condyloma. As noted above, the stromal component is a minor one.

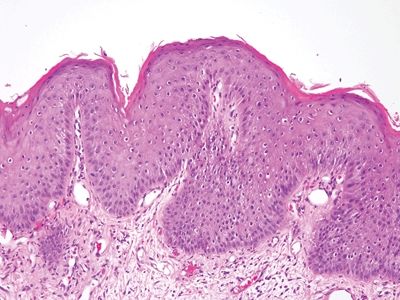

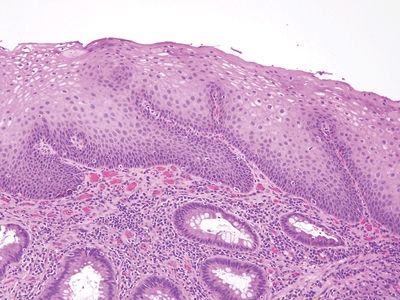

Figure 6.3.4 Fibroepithelial polyp (anal tag). This lesion is “all stroma,” with a coating of reactive squamous epithelium.

Figure 6.3.5 Fibroepithelial polyp (anal tag). These are reactive surface changes. The vacuoles around some of the squamous cells are small compared to the perinuclear halos that characterize condylomas.

Figure 6.3.6 Fibroepithelial polyp (anal tag). This example had a focus of AIN3, high-grade AIN on its surface. It is important to check the surface of even the most mundane-appearing squamous areas in the anus, including the surface of hemorrhoids.

6.4 Stromal changes in fibroepithelial polyp vs. Sarcoma

| Stromal Changes in Fibroepithelial Polyps | Sarcoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adults, no gender predilection | Adults—overall anal area sarcomas are extremely rare and can be associated with perianal skin |

| Location | At the junction between the anal canal and the skin | Anal canal or perianal skin |

| Symptoms | Patient notes small masses. Removal is suggested when they interfere with hygiene since removal is painful | Pain while defecating or patient notes mass |

| Signs | May be local hemorrhage | Mass |

| Etiology | May be related to mucosal prolapse, constipation, and anal fissures. More common in obese patients and persons with Crohn disease | Various but generally not known, depending on sarcoma type |

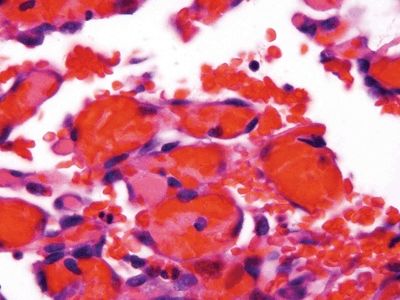

| Histology | ||

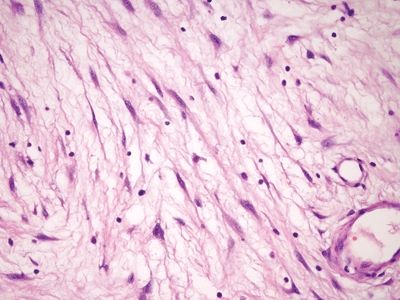

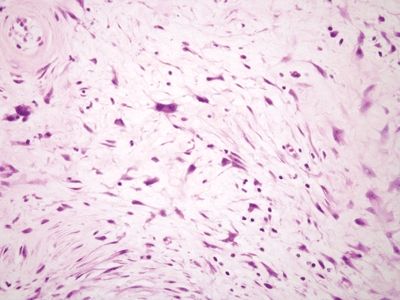

| 1. The subepithelial layer shows prominent proliferation and mild inflammation, but the overlying squamous epithelium forms a monolayer. There are enlarged atypical nuclei in the subepithelial tissue (Fig. 6.4.1) 2. The atypical stromal cells are scattered throughout an otherwise edematous stroma, and there is not much mitotic activity (Figs. 6.4.2 and 6.4.3) | 1. Variable according to sarcoma type but more cellular than stroma of anal tag (Figs. 6.4.4–6.4.6) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Removal if they interfere with hygiene or are embarrassing to the patient | Depends on sarcoma type |

| Prognosis | Excellent | Depends on sarcoma type |

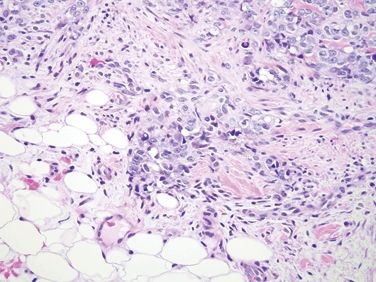

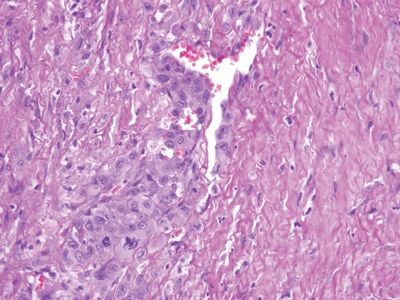

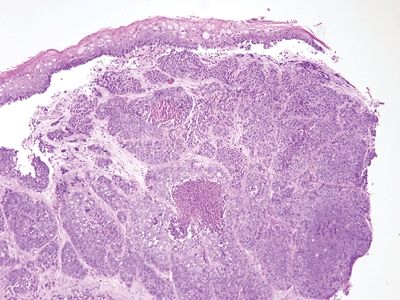

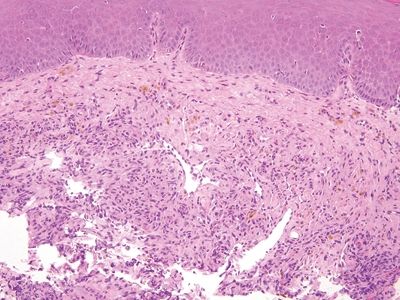

Figure 6.4.1 Stromal changes in fibroepithelial polyps. Since such lesions are constantly traumatized, they are prone to both reparative epithelial changes as well as reactive stromal changes. This lesion has squamous epithelial edema and a cellular stroma.

Figure 6.4.2 Stromal changes in fibroepithelial polyps. Higher magnification of the lesion shown in Figure 6.4.1.

Figure 6.4.3 Stromal changes in fibroepithelial polyps. This polyp has rather striking changes, but there is no mitotic activity, and the peculiar large fibroblasts have low nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios.

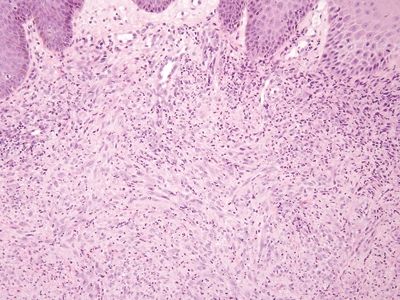

Figure 6.4.4 Kaposi sarcoma involving the anal canal. The hemosiderin and cellularity are both clues.

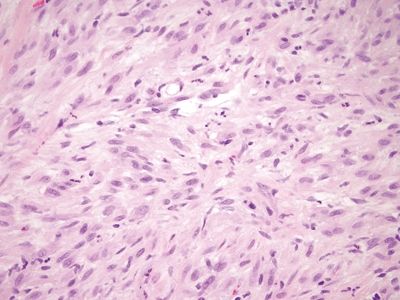

Figure 6.4.5 Epithelioid sarcoma–like hemangioendothelioma/pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma involving the anal area. Even if one is not familiar with this rare tumor, it clearly is far more cellular than the pseudosarcomatous change seen in Figure 6.4.3.

Figure 6.4.6 Epithelioid sarcoma–like hemangioendothelioma/pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma involving the anal area. Higher magnification of the tumor shown in Figure 6.4.5.

6.5 Reactive squamous changes vs. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia

| Reactive Squamous Changes | Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (AIN) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Typically adult | Adults, male predominance since so common in HIV-positive men who have sex with men |

| Location | Anal canal or perianal area | Most examples are found at the junction between the squamous mucosa and the rectal-type mucosa |

| Symptoms | None attributable to the reactive changes per se. The underlying etiology that caused the changes | None attributable to AIN |

| Signs | Not applicable | Can appear as a red plaque at colonoscopy but in high-risk patients, some undergo periodic anal screening with anal cytology. Reddish plaques can be seen that fail to retain Lugol iodine |

| Etiology | Various causes | Human papillomavirus (HPV) |

| Histology | ||

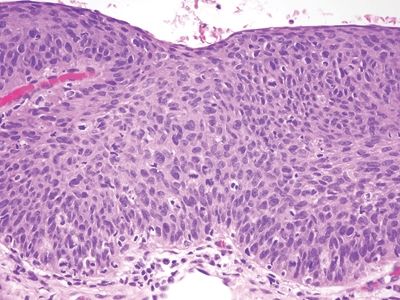

| 1. The squamous epithelium may be inflamed, and there may be erosions or ulcers (Fig. 6.5.1) 2. At high magnification, it is usually possible to see intercellular bridges (Fig. 6.5.2) 3. Cytoplasm is usually apparent with gradual maturation to the surface (Fig. 6.5.3) | 1. There is variable thickness replacement of the normal squamous epithelium with squamous epithelial cells displaying nuclear hyperchromasia (Figs. 6.5.4–6.5.6). The borders between the dysplastic cells are not sharp (squamous bridges not seen well). Most examples lack nucleoli in the cells in question 2. AIN can be graded by dividing the thickness of the neoplasia into the thirds of the thickness of the epithelium (AINI, AIN2, AIN3). There is controversy over whether to include AIN2 in low- or high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or high-grade neoplasia. P16 immunolabeling may be useful to stratify AIN2 into low- and high-risk groups (such that reactive cases be included in high-grade dysplasia). In our practice, we include AIN2 in high-grade AIN | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | None | Cryotherapy, chemical ablation |

| Prognosis | Generally excellent | Progression to invasive squamous cell carcinoma is uncommon, but patients are at risk for progression |

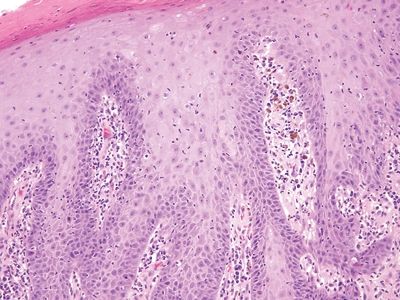

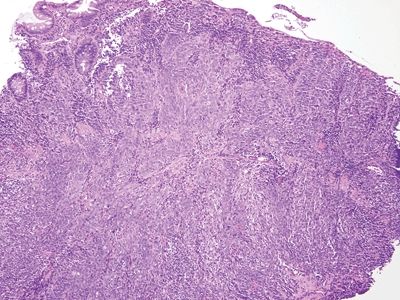

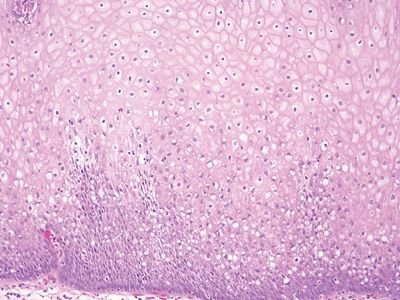

Figure 6.5.1 Reactive squamous changes. The nuclei lack hyperchromasia and mature toward the surface.

Figure 6.5.2 Reactive squamous changes. Well-glycogenized mucosa showing maturation.

Figure 6.5.3 Reactive squamous changes. The basal layer is expanded and mitotically active as part of reactive changes, but note that there is edema such that the intercellular bridges are readily apparent. They are difficult to see in nonreparative basal cells.

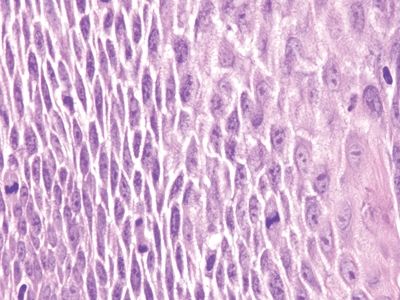

Figure 6.5.4 Anal intraepithelial neoplasia. This example is at the transition with colorectal-type mucosa. In this example of low-grade dysplasia, enlarged nuclei are easily identified even at low magnification.

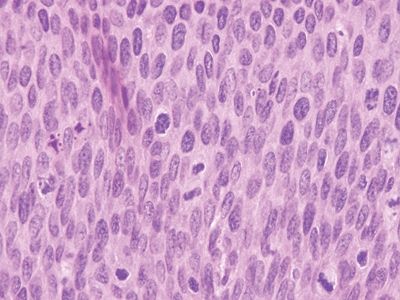

Figure 6.5.5 Anal intraepithelial neoplasia. This high-grade example is quite hyperchromatic.

Figure 6.5.6 Anal intraepithelial neoplasia. At high magnification, it is impossible to see squamous bridges.

6.6 Anal intraepithelial neoplasia extending into colorectal glands vs. Invasive squamous cell carcinoma

| Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (AIN) Extending into Colorectal Glands | Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/Gender | Adults with male predominance since so common in HIV-positive men who have sex with men | Adults with male predominance |

| Location | Most examples are found at the junction between the squamous mucosa and the rectal-type mucosa | Anal canal |

| Symptoms | None attributable to AIN | Anal pain, blood in stool |

| Signs | Can appear as a red plaque at colonoscopy but in high-risk patients, some undergo periodic anal screening with anal cytology. Reddish plaques can be seen that fail to retain Lugol iodine | Anal mass |

| Etiology | Human papillomavirus (HPV) | Most anal squamous cancers are related to human papillomavirus (HPV) |

| Histology | ||

| 1. The lesion is usually high-grade AIN, and a sharp demarcation between the AIN and the colorectal-type epithelium is apparent (Figs. 6.6.1 and 6.6.2) 2. The lamina propria is not sclerotic, and there is no typical keratinization in the AIN (Fig. 6.6.3) | 1. Anal squamous carcinomas appear similar to squamous cancers elsewhere 2. They are associated with desmoplasia and “paradoxical maturation with nucleoli and abnormal keratinization” (Figs. 6.6.4 and 6.6.5). The lamina propria is sclerotic and “overrun” by the tumor 3. Basaloid examples can be difficult to recognize but are associated with a desmoplastic response (Fig. 6.6.6) | |

| Special studies |

|

|

| Treatment | Cryotherapy, chemical ablation | Chemoradiation. Often, surgery is not needed |

| Prognosis | Progression to invasive squamous cell carcinoma is uncommon, but patients are at risk for progression | Overall, good and stage dependent. Patients tend to present early with low-stage lesions because of early symptoms. Remember that anal lesions are staged by size rather than depth of invasion |