CHAPTER 12

Agents for the treatment of portal hypertension

Introduction

Patients with end stage liver disease will suffer from portal hypertension and the complications associated with portal hypertension. These include variceal bleeding, ascites, hepatorenal syndrome, hyponatremia, and hepatic encephalopathy.

Portal pressure is the product of portal blood inflow and resistance to flow. Portal pressure increases initially secondary to an increased resistance to flow through the scarred-down, cirrhotic liver. In addition, there is an increase in portal venous inflow secondary to the splanchnic arteriolar vasodilatation. Portal hypertension then leads to the formation of porto-systemic collaterals. A hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) of > 10 mmHg will result in the formation of varices, and these will bleed at pressures > 12 mmHg. Pharmacologic agents are selected with the goal to decrease the HVPG to <12 mmHg or 20% from baseline. These include nonselective beta-blockers (propranolol, nadolol, and carvedilol), nitrates, vasopression analogs and somatostatin analogs.

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is a condition in which there is progressive kidney failure in a person with cirrhosis. It is a serious and often life-threatening complication of cirrhosis. Several pharmacological agents have been studied to treat HRS. The best available therapy is the use of vasoconstrictors (terlipressin, midodrine, noradrenaline) along with albumin. The most studied vasoconstrictor is terlipressin. Results from randomized controlled studies and systematic reviews indicate that treatment with terlipressin together with albumin is associated with a response rate of approximately 40–50%. However, terlipressin is not yet available in some countries, including the United States. If terlipressin is not available, most centers use “triple therapy,” that is octreotide given subcutaneously, albumin and midodrine.

Ascites is the most common complication of cirrhosis that leads to hospital admission. Once ascites develops, mortality is 15% in 1 year and 44% in 5 years. The hallmark of the treatment of ascites is the use of oral diuretics and salt restriction. The usual diuretic regimen consists of an oral dose of furosemide and spironolactone. Single-agent spironolactone is recommended for the first episode of ascites, but given its long half-life and the risk of hyperkalemia, it is often combined with furosemide. Furosemide is not used as a single agent in these patients, and most patients will require dual therapy.

Hypervolemic or dilutional hyponatremia, defined as a serum sodium < 130meq/L, is usually seen in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. It is seldom morbid unless it is rapidly corrected. It is estimated that 22% of patients with advanced cirrhosis have serum sodium levels < 130 mEq/L; however, in patients with refractory ascites or HRS, this proportion may increase to more than 50%. First-line treatment of hyponatremia is free water restriction and discontinuation of diuretics. If these do not work, one could consider an aquaretic medication such as tolvaptan.

Hepatic encephalopathy is the occurrence of confusion, altered level of consciousness and/or coma as a result of liver disease. It is caused by the accumulation in the bloodstream of toxic substances that are normally removed by the liver. It is generally precipitated by an infection, medication noncompliance, gastrointestinal bleeding, dehydration, electrolyte disturbance, shunt placement, or the use of medications that suppress the central nervous system (i.e., narcotics or benzodiazepines). Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy relies on suppressing the production of the toxic substances in the intestine and is generally done with the laxative lactulose or with nonabsorbable antibiotics.

This chapter will focus on drug therapies for patients with complications of portal hypertension.

Nonselective beta-blockers (NSBB)

Mechanism of action/pharmacology

Propranolol and nadolol are nonselective beta-blockers that block both β1 and β2 receptors competitively. In the treatment of portal hypertension, they act principally on β2 receptors, resulting in splanchnic vasoconstriction and a reduction in portal inflow. Carvedilol is a nonselective beta blocker as well as an α1 blocker. It is proposed that in addition to its β2 effects causing splanchnic vasoconstriction, it also has an additional effect by reducing intrahepatic portal resistance. For this reason, it is a more potent reducer of the HVPG than propranolol and nadolol.

NSBBs are almost completely absorbed following oral administration. Much of the administered drug is metabolized by the liver during its first passage through the portal circulation. However, somewhat less of the drug is removed during the first circulation through the liver after repeated administration, which accounts for a gradual increase in half-life of the drug after chronic oral administration.

Clinical effectiveness

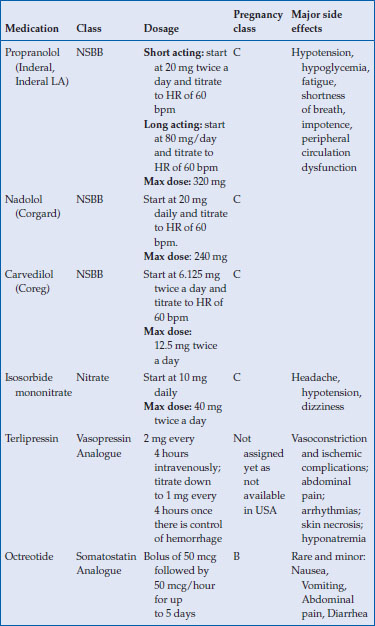

NSBBs are recommended for both primary prophylaxis and secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding. Patients who have survived a variceal bleed, should be treated with NSBBs and endoscopic band ligation to prevent rebleeding (secondary prophylaxis). Primary prophylaxis should be offered to patients with medium to large varices and those patients with small varices that are Childs B/C class or have red wale marks on their varices. Patients without varices should not be prescribed a NSBB, as a large multicenter placebo-controlled double-blind trial failed to show any benefit in the prevention of varix formation in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension but no varices at the time of enrollment. Dosages of specific agents are listed in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1 Medications used in the treatment of variceal prevention and bleeding

Toxicity

Although relatively well tolerated, there are some side effects of NSBBs that need to be mentioned. There will be a reduction in heart rate and blood pressure; the goal in treating patients is to maintain a heart rate of 55–60 beats per minute. If heart rate is continually <50 beats per minute and/or the systolic blood pressure is < 85 mm Hg then the NSBB should be discontinued. There also is a possible increase in airway resistance, making the presence of asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease a contraindication to the use of a NSBB. These agents also augment the hypoglycemic action of insulin and so patients who are susceptible for hypoglycemia should be educated about the warning signs of hypoglycemia.

NSBBs have been assigned a pregnancy class C by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These agents can lead to intrauterine growth retardation, neonatal hypoglycemia, hypotension and bradycardia. Only a small amount is expressed in breast milk if the patient is considering breastfeeding.

It should be noted that there is the potential for deleterious effects in patients with refractory ascites. In one single center study, 151 patients with refractory ascites were studied; 51% of patients were treated with NSBB. The median survival was 20 months in patients without a NSBB and only 5 months in patients receiving a NSBB. These authors have proposed that NSBB are contraindicated in patients with refractory ascites.

Nitrates

Mechanism of action/pharmacology

Isosorbide mononitrate (ISMN) is an organic nitrate and is a potent venodilator. Venodilators theoretically act by decreasing intrahepatic and/or portocollateral resistance. There is also a systemic hypotensive effect and the decrease in portal pressure may be more related to a decrease in flow secondary to the systemic hypotension rather than a decrease in resistance. ISMN has excellent bioavailability following oral administration.

Clinical effectiveness

NSBB are first line in the treatment of varices but nitrates can be used if there is a contraindication to a NSBB. Dosage of ISMN is listed in Table 12.1.

Toxicity

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree