Recurrent HCV infection is universal after transplantation in viraemic recipients [2]. Recurrent HBV infection occurs in 80% of patients in the absence of prophylactic therapies and, in the absence of specific therapeutic interventions, graft losses due to recurrent disease are frequent [3,4]. Therapeutic strategies for HBV have evolved over the past decade to the point that prevention of recurrent infection is now the norm for HBV patients undergoing LT. In contrast, for patients with HCV infection, therapies to prevent infection are not available and treatment of recurrent hepatitis after transplantation is only modestly effective.

HIV infection was previously regarded as a contraindication for liver transplantation. This is no longer the case due, in large part, to advances in antiretroviral therapy and prevention of opportunistic infections. With the increased longevity of HIV-infected patients, deaths due to the complications of end-stage liver disease have emerged as a major cause of mortality [5,6]. End-stage liver disease secondary to HCV and HBV are the most frequent indications for LT in HIV-infected individuals.

Hepatitis B and Liver Transplantation

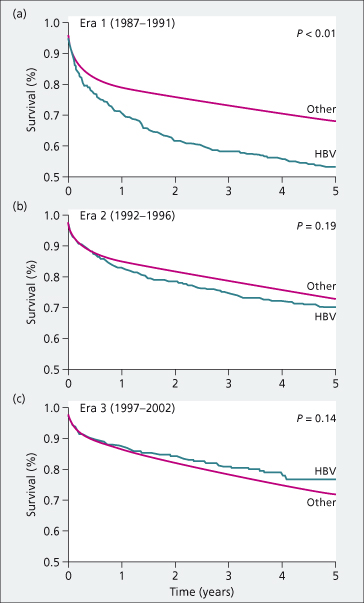

Historically, HBV-related liver disease was considered a relative contraindication for liver transplantation (LT) due of high rates of HBV recurrence, accelerated disease progression and patient survival rates of only 50% at 5 years [4]. Advances in HBV therapies in the mid-late 1990s improved outcomes dramatically (Fig. 37.2). With use of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) and nucleos(t)ide analogues, recurrent infection can be prevented in the majority of patients. The current 5-year survival rates for patients transplanted for HBV are approximately 80% [7]. Moreover, the widespread use of antiviral therapy for decompensated cirrhosis has resulted in fewer patients requiring LT for decompensated cirrhosis [1]. The primary indication for LT in HBV patients in most countries is HCC [1,8].

Fig. 37.2. Patient survival of US adult liver transplant recipients with HBV versus other indications in three different eras: Era 1 (1987–1991), Era 2 (1992–1996) and Era 3 (1997–2002). Survival was significantly improved in Eras 2 and 3 compared to Era 1.

Source [7].

Natural History and Factors Affecting Disease Recurrence

In the absence of prophylactic therapies, the risk of HBV reinfection after LT is approximately 80% overall, and related largely to the level of HBV replication at the time of transplantation [3]. Patients with fulminant hepatitis B, delta coinfection and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative chronic HBV have lower rates of recurrence than patients with HBeAg-positive chronic HBV. Recurrent infection has an accelerated course post-LT with cirrhosis developing within the first 3 years in the majority [3,4]. Both enhanced HBV replication and reduced host immune responses presumably contribute to the rapid disease progression. Additionally, there is a unique fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis variant, first described in HBV-infected transplant recipients in the early 1990s, characterized by high intrahepatic levels of HBV DNA, hepatocyte ballooning with cholestasis and a paucity of inflammatory cells [9]. Prior to the availability of effective antivirals, this represented the most severe and uniformly fatal form of recurrent HBV infection.

In the current era of prophylactic therapy, recurrent infection is infrequently seen. The factors associated with failure of prophylactic therapy are pre-LT HBV DNA levels and presence of drug-resistant HBV [10,11]. Additionally, two recent studies found HCC recurrence post-LT to be a significant risk factor for recurrent HBV infection [12,13], hypothesized to be due to micrometastatic HCC cells repopulating the new liver graft and inducing recurrence of both HBV infection and HCC after LT.

Low levels of HBV DNA in liver and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) has been reported in serum HBsAg-negative transplant recipients on long-term prophylactic therapy [14,15]. Clinically evident disease is absent. The clinical relevance of this low-level virus is unclear but these extrahepatic reservoirs may be a source of graft reinfection, supporting the need for life-long prophylaxis.

Treatment of Patients with HBV on the Waiting List

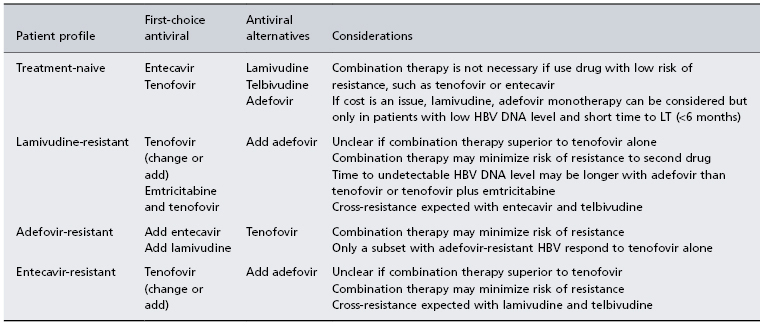

The goals of therapy in patients on the waiting list are the achievement of a low or undetectable HBV DNA level and avoidance of drug resistance. Treatment is long term and the choice of nucleos(t)ide analogue(s) used depends primarily on prior drug experience (Table 37.1). In treatment-naïve patients, the preferred drugs are those with potent antiviral activity and low risk of resistance, such as entecavir or tenofovir. Since all nucleos(t)ide analogues are renally cleared, doses need to be adjusted to renal function. Nephrotoxicity has been described with tenofovir and close monitoring for this complication is recommended. Interferon is contraindicated in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and not recommended in those with compensated cirrhosis since safer oral alternatives are available. Inhibition of viral replication prior to LT reduces the risk of reinfection of the graft post-LT. Achievement of sustained viral suppression pre-LT is associated with stabilization of liver disease, delay in need for LT and improved pre-LT survival [16,17]. Patients with HBV DNA levels above 10 000 IU/mL at time of LT and those with drug-resistant HBV pre-LT have a higher risk of recurrent HBV despite prophylaxis [11]. Since virological breakthrough in patients with underlying cirrhosis can result in worsening of liver function and even death from rapidly progressive liver failure, close monitoring for the development of resistance is important. If salvage therapy is initiated early after virological breakthrough is identified, clinical outcomes are not affected [18,19]. For those patients failing to achieve an undetectable HBV DNA level with single-drug therapy or who have drug resistance, combination antiviral treatment is recommended [20].

Table 37.1. Antiviral therapy in HBV-infected patients on the waiting list

Preventing HBV Recurrence Post-Transplantation

Preventive therapy begins from the time of transplantation and continues life long. The combination of HBIG and one or more nucleos(t)ide analogues is a highly effective prophylactic therapy [21]. HBV recurrence is reported in 10% or less of patients receiving combination HBIG and lamivudine with up to 5 years’ follow-up [10,22]. The published literature on the efficacy and safety of other nucleos(t)ide analogues such as entecavir and tenofovir in combination with HBIG are sparse, but are predicted to be effective (possibly more effective because of lower risk of resistance). The doses of HBIG given vary greatly from centre to centre. Early protocols using HBIG alone provided doses of 5000–10 000 IU monthly to maintain anti-HBs titres of above 500 IU/L during the first week post-LT, above 250 IU/L during weeks 2–12 post-LT, and above 100 IU/L after week 12, as these levels best predict success of prophylaxis [23]. Lower doses of HBIG can be used when combined with nucleos(t)ide analogues, especially if patients have an undetectable HBV DNA level at time of LT. The Australasian Liver Transplant Study Group used intramuscular HBIG dosed at 400 to 800 IU daily for the first week, weekly for the first month, and then monthly thereafter in combination with lamivudine. In this study, more than 50% of patients had undetectable HBV DNA at the time of LT and 96% success in preventing recurrent HBV at 5 years was reported [10].

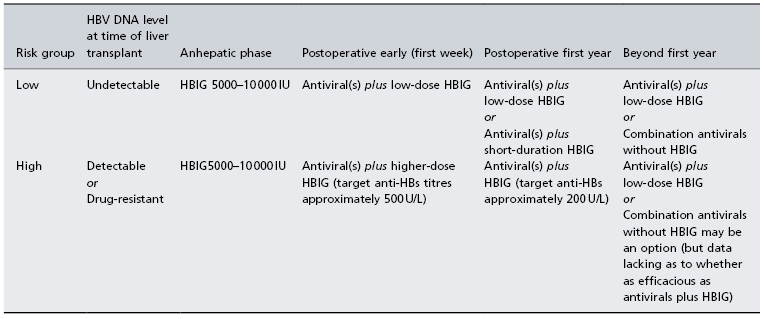

Factors associated with failure of prophylaxis include pre-LT HBV DNA levels and history of drug-resistant HBV. Prophylactic strategies should be tailored to the replication status of the patient at the time of transplantation and history of drug resistance (Table 37.2). HBIG use is limited by cost and the need for parenteral administration. Prophylactic regimens using lower doses of HBIG, less frequently administrated and/or given by the intramuscular route are preferable to minimize exposure to human blood products and increase convenience. Protocols using limited-duration HBIG or replacement of HBIG by another nucleos(t)ide analogue with complementary resistance profile have been associated with low rates of recurrence with 2–4 years’ follow-up [24–26]. Combined nucleoside and nucleotide analogue therapy may also be an alternative, especially after the first year when risk of recurrence is low [26].

Table 37.2. Prevention strategies for HBV in liver transplant recipients*

*Approach suggested by the author based upon available retrospective data.

HBIG, hepatitis B immune globulin.

Anti-HBc Positive Donors

Anti-HBc positive donors are routinely utilized in many transplant programmes, especially in countries where HBV is endemic [27]. These organs are a recognized source of ‘de novo’ HBV in transplant recipients and the risk of post-LT infection correlates with the antibody status of the recipient [28,29]. Recipients lacking both anti-HBs and anti-HBc have a 60–70% risk of HBV infection, those with anti-HBc or anti-HBs alone have a risk of 10–20%, and those with anti-HBc and anti-HBs have the lowest risk, 0–5% [28]. When possible, anti-HBc-positive organs are best used in HBV-infected transplant recipients, as prophylaxis is already provided. In HBsAg-negative recipients, prophylactic therapy is recommended to prevent de novo infection [29].

A recent survey of LT programmes in the USA, Canada, Europe and Asia found that nucleos(t)ide analogues given for an indefinite duration was the most common prophylactic approach, with lamivudine used by the majority [30]. Approximately 60% of LT programmes also used HBIG for variable periods post-LT, and whether HBIG added to nucleos(t)ide analogues therapy reduces the risk of prophylaxis failure is unknown. The least costly form of prophylaxis is lamivudine monotherapy. Antivirals with a lower rate of resistance, such as tenofovir or entecavir, may be considered although the risk of virological breakthrough in this setting is predicted to be very low [28].

Management of Recurrent HBV in Liver Transplant Recipients

HBV recurrence after liver transplantation is usually the result of failed prophylaxis, either due to non-compliance or the emergence of drug-resistant HBV. Recurrence of HBV infection has been traditionally defined by reappearance of HBsAg in serum. However, with use of sensitive PCR assays, recurrence may be first manifested as reappearance of HBV DNA in serum in the absence of HBsAg. Serological evidence of recurrence is accompanied by elevated levels of HBV DNA in serum followed by clinical evidence (elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels and hepatitis on biopsy) of recurrent disease.

To minimize fibrosis progression and graft loss due to recurrent disease, life-long control of viral replication is essential post-LT. The availability of safe and effective antivirals has allowed the majority of patients with recurrent HBV infection to survive without graft loss from recurrent disease. There is no role for HBIG once serum HBsAg becomes persistently detectable. The choice of antivirals is guided by prior antiviral history and drug resistance profiles. Lamivudine, adefovir or telbivudine are not recommended as a single-drug therapy due to the high risk of resistance but may be used as part of a combination regimen. In patients with drug-resistant HBV, a nucleoside analogue (lamivudine, telbivudine, entecavir, emtricitabine) combined with a nucleotide analogue (adefovir or tenofovir) offers the best option for long-term suppression [20]. Regardless of the therapy chosen, close monitoring for initial response and subsequent virological breakthrough is essential to prevent disease progression and flares of hepatitis. Patients with a suboptimal response to a specific drug therapy, warrant a change of drug(s), with add-on therapy generally recommended over sequential, single-drug therapy.

Retransplantation

Retransplantation for graft failure due to recurrent disease is infrequent in the current era of HBV therapeutics. Retransplantation is not contraindicated in patients with recurrent HBV disease and outcomes are expected to be good, if effective prophylactic therapy can be provided [31,32]. Since most patients who require retransplantation have failed prior antiviral therapies, testing for drug resistance mutations prior to transplantation will help select an effective antiviral therapy. In this higher-risk group, combination prophylaxis of antivirals and HBIG is recommended.

Hepatitis C and Liver Transplantation

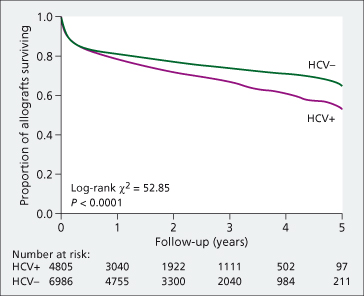

HCV is the most common indication for LT in the USA and Europe, with a growing proportion undergoing LT for the primary indication of HCC [1]. Graft survival is reduced in HCV-infected transplant recipients compared with non-HCV patients, with a 23% increased risk of death at 5 years post-LT [33] (Fig. 37.3). In the European Liver Transplant Database, the patient survival rate for HCV patients is 66% at 5 years and 54% at 10 years (personal communication V. Karam, European Liver Transplant Registry, March 2009). Recurrent HCV disease is the most common cause of graft loss.

Fig. 37.3. Graft survival of US adult liver transplant recipients with and without HCV. Anti-HCV-positive transplant recipients had a significantly lower rate of survival than transplant recipient without HCV with 1, 3 and 5-year survival rates of 76.9%, 66.4% and 56.8% compared to 80.1%, 73.3% and 67.7% respectively (P < 0.001).

Source [33].

Natural History and Factors Associated with Severe Recurrent Disease

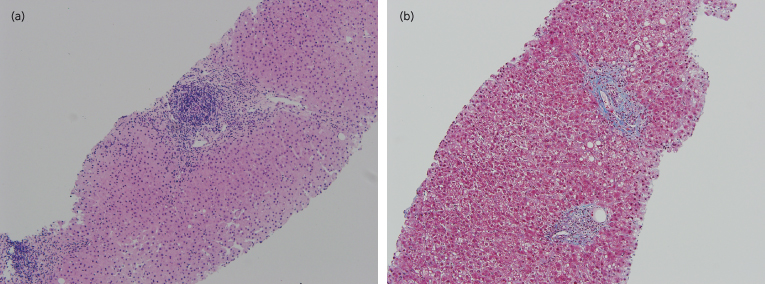

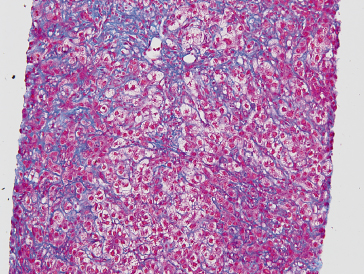

Recurrence of hepatitis C typically presents with elevated liver tests or histological findings of hepatitis within the first year post-LT [34]. HCV RNA levels are, on average, approximately 1−log10 IU/mL higher post-LT compared to pre-LT. HCV RNA levels correlate poorly with disease severity [35]. Chronic hepatitis (Fig. 37.4) evolves to cirrhosis at a variable rate but more rapidly than in non-transplant patients. The cholestatic variant of hepatitis C is the most severe presentation of HCV recurrence, and is frequently associated with high HCV viral levels and the rapid development of graft failure (Fig. 37.5) [36]. Several donor, recipient and transplant-related factors have been associated with poor post-transplant outcomes (Table 37.3). Potentially modifiable factors include donor age, prolonged cold ischaemia time, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, acute rejection requiring treatment and post-transplant insulin-resistance or diabetes.

Table 37.3. Factors associated with higher risk of recurrent cirrhosis in HCV patients

| Category | Specifics | Strength of association |

| Recipient-related | HIV coinfection African-American race Female gender | +++ + + |

| Donor-related | Older donor age Longer cold ischaemia time Longer warm ischaemia time | +++ +++ + |

| HCV-related | HCV genotype 1 High HCV viral load pre-liver transplantation | +/− + |

| Transplant-related | Treated acute rejection Cytomegalovirus infection Insulin-resistance/ diabetes Steatosis | +++ +++ +++ + |

Fig. 37.4. Photomicrographs of recurrent chronic HCV disease. (a) Photomicrograph showing a mild portal-based lymphocytic infiltrate and mild interface activity. The bile ducts are intact. (H&E stain) (b) Early fibrosis surrounding portal tracts with a few short fibrous septa. (Trichrome stain)

Courtesy of Dr Vivian Tan, University of California San Francisco.

Fig. 37.5. Photomicrograph of cholestatic variant of recurrent hepatitis. This trichrome stain highlights the centrilobular hepatocellular ballooning with pericellular fibrosis and minimal portal or lobular inflammation.

Courtesy of Dr Vivian Tan, University of California San Francisco.

Older donors are associated with a higher rate of graft loss but HCV-infected patients are affected more than non-HCV patients. The risk of graft loss in HCV-infected recipients with donors aged between 41 and 50, 51 and 60, and over 60 years of age are 67% (HR = 1.67, 95% CI: 1.34–2.09), 86% (HR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.48–2.34) and 221% higher (HR 2.21, 95% CI: 1.73–2.81) respectively, than those recipients with donor under age 40 years [37]. The increase in graft loss reflects the heightened rate of progression to cirrhosis in those with older donors [38–40]. A recent consensus conference on use of extended criteria donors, recommended that ‘elderly donors’ not be utilized in HCV-infected patients [41].

There is a strong positive association between treated acute rejection (≥1 episode) and risk of recurrent cirrhosis [42]. In recognition of this association, experts recommend a conservative approach to treatment of rejection, with avoidance of corticosteroid boluses and lymphocyte-depleting drugs when possible [43]. The goal is to provide sufficient immunosuppression to prevent moderate to severe rejection while simultaneously avoiding excessive immunosuppression.

Prolonged cold ischaemia time (≥12 hours) [44,45] is associated with higher rates of graft loss and risk of developing severe fibrosis. Prolonged warm ischaemia time (≥90 minutes) has been linked with worse outcomes in one study [46]. CMV infection, though an infrequent post-transplant complication, is a strong risk factor for more severe fibrosis in patients with HCV infection [47–50]. CMV may affect HCV disease progression via its immunomodulatory effects and cytokine-mediated profibrogenic effects. Post-LT diabetes, insulin resistance and steatosis have been variably associated with a higher risk of advanced fibrosis and probably reflect overlapping metabolic risks [51–53]. Both CMV infection and post-LT diabetes are factors that are potentially modifiable. Since HCV-infected transplant recipients have a higher prevalence of de novo post-transplant diabetes compared to non-HCV patients [54–56], immunosuppressive regimens with less diabetogenic potential may reduce the risk of both diabetes and fibrosis progression.

Initial studies suggested post-LT outcomes for living donor recipients with HCV are worse compared to deceased donor liver transplant recipients with HCV [57–59]. Subsequently, studies showed similar graft and patient survival once centres had experience with living donor liver transplantation [60]. Additionally, there are no significant differences in the time to development of HCV recurrence, severity of HCV recurrence or fibrosis progression rates between living versus deceased donor recipients with follow-up periods up to 2 years [61–64].

Anti-HCV-Positive Donors

Overall patient and graft survival are not affected by use of anti-HCV-positive donors [65–68]. One study reported significantly worse survival with older (>50 years of age) anti-HCV-positive donors compared to older anti-HCV-negative donors, though this finding requires confirmation [65]. In a detailed virological study of 14 patients with genotype 1 who received HCV-infected genotype 1 livers, an approximately equal proportion of patients had persistence of the recipient strain versus superinfection and takeover of the donor strain post-transplantation [69]. The rate of histological disease progression appears to be comparable in patients receiving an anti-HCV-positive versus anti-HCV-negative donor, with one study finding a longer disease-free survival when the donor strain dominated post-LT [70]. Additional recommendations regarding use of anti-HCV-positive donors include informed consent of recipients regarding potential risks and the use of liver biopsy to exclude donor organs with any evidence of fibrosis or more than minimal inflammation [41,66].

Overview of Management of HCV Infection in Transplant Recipients

Approach to Immunosuppression

Despite many studies, there are few definitive recommendations that can be made regarding the ‘best’ immunosuppression for HCV-infected patients. Areas of controversy include the type of calcineurin inhibitor (ciclosporin versus tacrolimus), type of antiproliferative drug (azathioprine versus mycophenolate mofetil), and the risk–benefit of corticosteroids. Since acute rejection requiring treatment with corticosteroid boluses and lymphocyte-depleting drugs is associated with a higher risk of severe post-transplant HCV disease, the goal of immunosuppression is to provide sufficient immunosuppression to avoid acute rejection that requires treatment with these drugs.

Ciclosporin has anti-HCV effects in vitro [71]. However, studies have not firmly established a benefit of ciclosporin over tacrolimus in HCV-infected transplant recipients. A systematic review of five studies (366 patients total) found no statistically significant difference in graft survival (RR = 0.86; 95% CI: 0.61–1.21) between tacrolimus versus ciclosporin-based immunosuppression but the quality of the studies was insufficient to evaluate the relationship between type of calcineurin inhibitor and risk of recurrent cirrhosis [72].

Retrospective studies also suggest azathioprine may be better for HCV-infected patients than mycophenolate mofetil, even though mycophenolate mofetil shares some mechanisms of action to ribavirin (inhibition of inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase). A recent systematic review concluded data were insufficient to recommend one antiproliferative drug over the other [73]. In the prospective HCV-3 study, there were no differences in HCV disease severity after 2 years in patients receiving tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone for immunosuppression compared to those receiving tacrolimus and prednisone [74].

The strongest link between lymphocyte-depleting agents and risk of recurrent cirrhosis is within the context of treating acute rejection. Interleukin-receptor antagonists are not a risk factor [74], except alemtuzumab, which has been associated severe recurrent HCV [75]. Finally, while corticosteroid boluses for treatment of acute rejection are associated with a higher risk of cirrhosis, there are conflicting data on the risks of maintenance corticosteroids. There is no difference in severity of HCV disease in patients receiving steroid-free immunosuppression compared to corticosteroid-containing immunosuppression [68].

Pretransplant Treatment of HCV-Infected Patients on the Waiting List (Table 37.4)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree