The four types of adenoma are: hepatocyte nuclear factor-1α (HNF-1α) inactivated, β-catenin activated, inflammatory and unclassified. HNF-1α-inactivated adenomas show steatosis, absence of significant inflammation and decreased staining for liver fatty acid binding protein. In β-catenin-activated adenoma, nuclear atypia and pseudoglandular differentiation are frequent and tumour cells stain for glutamine synthetase and β-catenin. The inflammatory type often has ductular differentiation adjacent to the arterial supply, inflammatory infiltration, sinusoidal dilatation (accounting for an earlier designation as ‘telangiectatic adenoma’) and staining with serum amyloid A protein and C-reactive protein.

Clinical Features

Women are affected more than men, usually within the childbearing years. The patient may present with a right upper quadrant mass. Hepatic tenderness and abdominal pain are associated with intratumoural haemorrhage; this may be followed by rupture and intraperitoneal haemorrhage. Serum biochemical tests may be normal. In the presence of tumour necrosis, transaminases and alkaline phosphatase may be elevated. Serum α-fetoprotein is normal. Progression to hepatocellular carcinoma occurs in up to 8% of all patients with adenoma [8–10]. The risk of malignant transformation in men is 40–50%.

Most patients have a recognizable risk factor, especially long-standing exposure to oral contraceptives in approximately 90% of cases. Other risk factors include anabolic steroid or danazol use and glycogen storage disease (type 1 and 3). HNF-1α-inactivated adenomas occur almost exclusively in women and are associated with maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 3 (MODY3) diabetes. Most cases of adenomatosis are of this type. β-catenin-activated adenomas are often associated with glycogenosis, male hormone administration and male gender, and increased risk of malignant transformation. Inflammatory adenoma is often associated with elevated serum C-reactive protein, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and, rarely, with fever and anaemia. This type has an increased risk of haemorrhage; malignant transformation may occur.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis is usually that of focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) because of the similar demographic profiles. Clinical imaging techniques can distinguish these two lesions in the majority of cases. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography is particularly effective in this differential [4]. Magnetic resonance imaging is especially useful to detect steatosis or haemorrhage [9].

Malignant transformation of adenoma can be suspected if there is a nodule-in-nodule imaging pattern or there is rapid clinical growth; most cases with malignant change are found in lesions greater than 8 cm diameter. Serum α-fetoprotein is usually not elevated in these cases.

Histologically, FNH almost always has some evidence of ductular proliferation. Central degenerative changes may cause adenoma to mimic FNH clinically and histologically. The pattern of glutamine synthetase staining differs in FNH and adenoma. Hepatocellular carcinoma is suggested by wide or irregular plates and mitotic figures. A histologically low-grade hepatocellular nodule in a cirrhotic liver is unlikely to be an adenoma; in this context the lesion is more likely to be a dysplastic nodule, well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma or arterialized regenerative nodule.

Management

Adenoma is a usually a stimulated lesion. Thus, hormones and other stimuli must be stopped. In many cases the lesions will regress. Control of glycogen storage disease may also allow regression. Surgical excision should be considered for lesions that are symptomatic or measure greater than 5 cm diameter. Adenomas in men should always be excised because of the high risk of malignant transformation [9,10]. The risk of haemorrhagic complication in pregnancy appears to be low but enlargement may occur [9]. Bleeding adenomas may be controlled by arterial embolization, decreasing the morbidity of subsequent excision [11]. When lesions are multiple, complete excision may not be possible; however, this is not an indication for transplantation [9].

Dysplastic Nodule

Dysplastic nodules are early neoplastic precursors of hepatocellular carcinoma [2,12]. They are asymptomatic anomalies, less than 2 cm in diameter, found in cirrhotic livers during imaging or macroscopic examination. The serum α-fetoprotein level is usually less than 200 ng/mL. Malignant transformation occurs in 50% of biopsy proven high-grade dysplastic nodules followed for 2 years [13]. Malignant transformation is suggested by imaging features of hypervascularity, increasing size or nodule-in-nodule configuration.

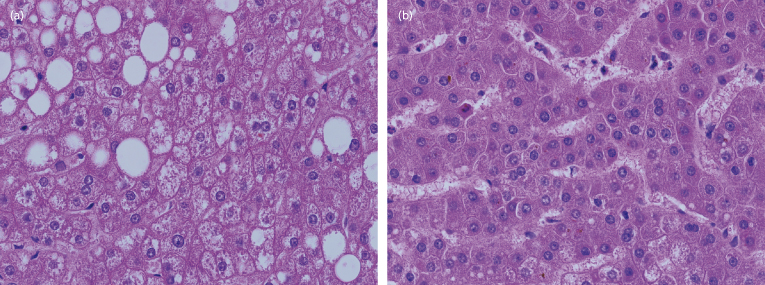

By definition, dysplastic nodules show histological atypia that is insufficient for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (Fig. 34.2). The atypical changes are part of a gradual spectrum so that histological diagnosis is difficult. The immunohistochemical profile is useful to detect the transition to malignancy [14].

Fig. 34.2. Dysplastic nodule (a) and well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (b), both from the same liver. The dysplastic nodule shows low N/C ratio and plates one to two cells in thickness. The carcinoma shows increased N/C ratio with plates two to four cells in thickness.

The differential diagnosis of space-occupying lesions in cirrhotic livers includes dysplastic nodule, hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, haemangioma, simple cyst, metastasis, arterialized regenerative nodule and regional parenchymal extinction.

Dysplastic nodules are not histologically uniform. Thus, needle biopsy diagnosis is susceptible to sampling error and complete excision is necessary to exclude focal carcinoma. Nevertheless, biopsy can be definitive and is useful to expedite therapy. In selected patients, it may be appropriate to treat the lesion with alcohol- or radiofrequency ablation immediately following the biopsy. Ablation without prior biopsy is not recommended.

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is a benign nodule composed of hepatocytes with a characteristic appearance on imaging and histology. FNH is the second most frequent benign liver nodule (after haemangioma), occurring in 0.8% of the adult population [15] with a 10 : 1 female to male ratio. Although women usually present in their reproductive years and the majority have taken oral contraceptives, a pathogenic role of hormones has not been proven [10,16]. Most lesions are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. Large lesions may present with pain or an abdominal mass.

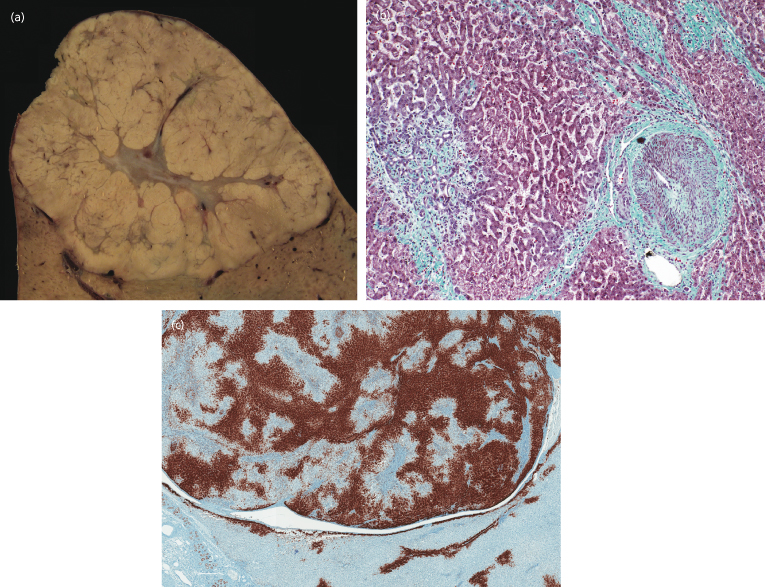

Most lesions are less than 2 cm in diameter but may be as large as 10 cm or more (Fig. 34.3). Lesions are multiple in a third of patients. Pedunculated lesions are not rare. Histologically, the lesion consists of normal hepatocytes with regions of fibrous tissue containing large arteries and proliferating bile ducts. The background liver is usually normal, although hepatic haemangioma is found in 20% of cases.

Fig. 34.3. Focal nodular hyperplasia. (a) Cut section of a 6-cm lesion showing fibrous septation and central scar. (b) Microscopic view. The lesion is composed of benign-appearing hepatocytes supplied by altered portal tracts. Note a thick-walled dystrophic vessel (right) and proliferating bile ducts (left). (c) Focal nodular hyperplasia at low magnification stained to show glutamine synthetase. This enzyme is strongly expressed near hepatic veins but not in periarterial regions, giving the classic map-like pattern. Outside the lesion (bottom) a normal, perivenous staining pattern is seen.

FNH is thought to be a hyperplastic response to an artery-to-portal vein shunt [17]. Although usually cryptogenic, FNH may be initiated by local trauma or other cause of venous injury in an otherwise normal liver [18]. Classical FNH and other arterialized regenerative nodules can occur with abnormalities such as portal vein agenesis, portal vein thrombosis, patent ductus venosus, hepatic vein thrombosis and hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia [19]. Molecular studies have usually demonstrated a polyclonal pattern, as would be expected in a reactive lesion [20,21].

Interpretation of small biopsies is occasionally difficult using routine stains. However, the recent introduction of the glutamine synthetase stain allows for much improved diagnostic accuracy (Fig. 34.3c).

Diagnosis

A confident diagnosis can be made by imaging when there is a hypervascular mass supplied with a single central artery and centrifugal blood flow [4]. These features are most easily identified on contrast enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS). A central scar is seen in 60% of lesions on imaging. In its absence, confusion with hepatocellular adenoma or hepatocellular carcinoma may occur. Liver biopsy is not usually necessary but is very useful when diagnosis is in doubt, especially when CEUS is not available or a central scar is not identified.

Clinical Behaviour and Management

FNH is a static lesion; if there is growth, an alternate diagnosis should be entertained [22,23]. Rupture and malignant transformation have been reported only rarely and need to be confirmed. FNH should be treated conservatively without surgery. However, exceptions may be considered when the diagnosis is not certain or if the lesion is large, pedunculated or symptomatic. The presence of FNH is not a contraindication to hormone therapy or pregnancy.

Arterialized Regenerative Nodule

This category of nodules includes FNH but also similar lesions that lack some of the classical features of FNH. These lesions have been reported with various designations including incomplete FNH, pre-FNH, FNH-like nodules in cirrhosis, regenerative nodules in Budd–Chiari syndrome, nodular hyperplasia in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia, hyperplasia adjacent to metastatic tumour (peritumoural hyperplasia) and large regenerative nodule in nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH). Their common characteristics are benign hepatocytes, arterialized (CD34 positive) sinusoids, and hypervascularity on various imaging modalities. This category is useful when a lesion has not been fully characterized or when some features of FNH are lacking on histological examination.

Nodular Regenerative Hyperplasia

This condition is defined histologically by the presence of micronodules 1–2 mm in diameter delineated by regions of atrophy and without fibrous septa [24,25].

NRH is a non-specific response to irregular obliteration of small portal veins. This obliteration is usually caused by local portal tract inflammation of any cause, especially with systemic arteritis (rheumatoid arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis), portal vein thrombosis (myeloproliferative diseases, hypercoagulable states), neoplastic infiltration (especially lymphoma), early stage primary biliary cirrhosis and toxic injury (e.g. methotrexate, azathiooprine, oxaliplatin) [26]. NRH and non-cirrhotic portal hypertension rarely occurs after liver transplantation. These events are explained in many cases by portal vein thrombosis or anastomotic stricture [27].

The lesions may be asymptomatic or associated with portal hypertension. Patients with portal hypertension present with splenomegaly and varices, and less often with ascites [28]. The liver is enlarged if there is underlying myeloproliferative disease. Hepatic vein wedge pressure may be moderately elevated. Liver function is normal but alkaline phosphatase is commonly elevated. Portocaval shunting procedures are well tolerated.

Imaging usually shows minimal, non-specific changes. There may be features of arterialization and collateral drainage. Occasionally, livers with NRH contain larger nodules that are visible on imaging studies. These are usually coexistent arterialized regenerative nodules [29]. However, the possibility of hepatocellular or metastatic carcinoma should be considered.

Liver biopsy is useful when the clinical situation demands exclusion of cirrhosis. A needle biopsy less than 2 cm in length may not be sufficient to exclude macronodular cirrhosis and incomplete septal cirrhosis.

Focal Fatty Change and Focal Fatty Sparing

Regional variation in amount of liver cell fat can produce entities called pseudolesions or pseudotumours, usually discovered during imaging [30–32]. Focal fatty change generally occurs near the hilum, possibly as a response to insulin delivery from a pancreatic vein into the peribiliary plexus [33]. The reverse effect of focal fatty sparing in an otherwise fatty liver can occur when a region near the hilum is perfused with low-insulin blood from a pyloric vein [34]. Because focal fatty sparing can only occur in the presence of fatty liver disease, most of these patients have alcoholism or obesity.

Focal fatty change also occurs under the hepatic capsule in patients receiving insulin into the peritonal cavity as part of peritoneal dialysis therapy [35]. This was the original observation leading to the discovery that hyperinsulinaemia is the key to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Biliary and Cystic Lesions

Bile Duct Adenoma

This is a subcapsular nodule composed of small uniform duct-like glands [36]. It has been suggested that this lesion is a hamartoma arising from peribiliary gland elements [37]. The lesion is commonly mistaken for metastatic carcinoma. The absence of atypia and glandular variation helps make the diagnosis. A variant with clear cell morphology closely mimics renal cell carcinoma [38].

Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm (Formerly Biliary Cystadenoma)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree