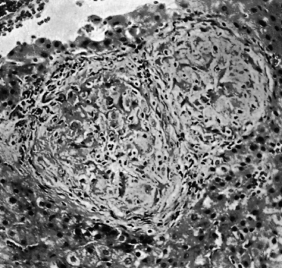

Fig. 31.2. Healing hepatic sarcoid. Two adjacent lesions are acquiring a structureless hyaline appearance and are surrounded by a connective tissue capsule. (H & E, ×90.)

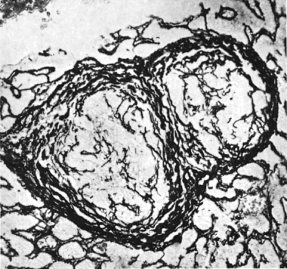

Fig. 31.3. Same section as in Fig. 31.2 stained to show reticulin formation around the granulomas. (Modified silver, ×90.)

There are some specific findings and subtypes of granulomas with suggestive diagnostic features:

- Sarcoid-type granulomas are small, well formed and discrete. Multinucleated giant cells may be present (see Fig. 31.1), and occasionally a central area of eosinophilic necrosis. Caseation is absent.

- Necrotizing or caseating granulomas are small to large, well formed with a necrotic centre. The histiocytic rim may have a palisade pattern and fibrosis is variable. They are associated with fungal infections and rarely with tuberculosis or Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

- Lipogranulomas comprise poorly formed perivenular aggregates of histiocytes and macrophages, some containing fat. They are often associated with fatty liver. They are due to deposition of mineral oils used in the food industry.

- Microgranulomas consist only of a cluster of six or less histiocytes. They have many associations and probably represent a non-specific reaction to cell necrosis.

- Fibrin-ring granulomas are typical of Q fever, but are also seen as drug reactions (e.g. carbamazepine, allopurinol). They are also described with acute hepatitis A.

In addition to the routine haematoxylin and eosin and reticulin staining of liver biopsies to assess liver architecture, finding granulomas may prompt further specific staining, for example Ziehl–Neelsen and diastase–PAS for acid-fast bacilli and fungi. Positive findings with these are very helpful, but negative findings do not exclude the infections.

Clinical Syndrome of Hepatic Granulomas

Granulomas are usually asymptomatic. The liver is palpable in only 20% of patients. Very rarely the picture is of active liver disease with marked functional disturbance and liver cell destruction and fibrosis on liver biopsy, or of the rare syndrome of ‘granulomatous hepatitis’. Serum alkaline phosphatase elevations are the commonest biochemical abnormality and bilirubin levels usually normal. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme is increased, a finding not specific for sarcoidosis.

Table 31.1 shows the investigations that are likely to establish the aetiology when granulomas have been found on biopsy; the precise diagnostic path will be modified by clinical acumen and epidemiological probabilities.

Specific Causes and Syndromes

Infections

Granulomas can occur with almost all types of infection. The most frequent are tuberculosis, brucellosis, toxoplasmosis, atypical mycobacteriosis, fungal diseases, syphilis, leishmaniasis and the infestations, schistosomiasis and toxocariasis (Table 31.2). In many instances, the granulomas are ill formed.

Table 31.2. Hepatic granulomas associated with infections

| Mycobacteria | M. tuberculosis |

| M. avium-intracellulare | |

| Leprosy | |

| Bacteria | Brucella |

| Spirochaetes | T. pallidum |

| Fungi | Histoplasmosis |

| Coccidioidomycosis | |

| Blastomycosis | |

| Protozoa | Toxoplasmosis |

| Helminths | Schistosomiasis |

| Toxocara canis | |

| Fasciola hepatica | |

| Ascaris lumbricades | |

| Rickettsiae | Q fever |

| Viruses | Hepatitis A |

| Hepatitis C | |

| Cytomegalovirus |

Mycobacteria

Miliary dissemination accompanies the primary complex of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and is also common with chronic adult tuberculosis. Liver biopsies in patients with tuberculosis have shown positive results in about 25%—providing a useful diagnostic tool in tuberculous meningitis when other methods have failed, and in miliary tuberculosis at the stage of an indeterminate pyrexia. In such cases Ziehl–Neelsen stains should be performed, an unfixed portion of the biopsy cultured for tubercle bacilli and PCR analysis for mycobacterial DNA has been advocated. Importantly, the Ziehl–Neelsen technique is insensitive—although specific—and a negative result does not rule out mycobacterial infection.

In western practice, the diagnostic distinction is often from sarcoidosis. The granulomas may be indistinguishable. Acid-fast bacilli are often difficult to find in mycobacteria-affected livers. Destruction of the reticulin framework, irregularity of the contour with a particularly dense cuff of lymphocytes and less numerous lesions with a tendency to coalesce all suggest tuberculosis.

Rarely, fulminant liver failure can result from tuberculosis. Granulomas are found after BCG vaccination, especially in the immunosuppressed.

Leprosy

Hepatic granulomas indistinguishable from those of sarcoidosis may be found in 62% of patients with lepromatous leprosy compared with the tuberculoid form, when only 21% are positive. Mycobacterium leprae bacilli are sometimes present.

Other Bacteria

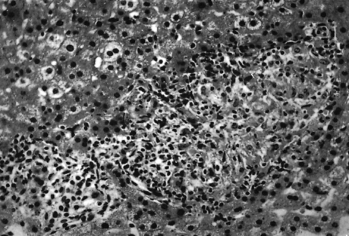

Brucella abortus infection may be complicated by granulomas. Hepatic tenderness and mild elevations of transaminases and alkaline phosphatase may be found in the acute stage. Histology shows a non-specific reactive hepatitis. Granulomas resemble those of sarcoidosis although they tend to be smaller and less demarcated (Fig. 31.4). Healing results in scarring. Necrotizing microgranulomas may be found in the bone marrow.

Fig. 31.4. Brucellosis. Granulomas in the liver; the smaller is little more than a collection of round cells. (H & E, ×170.)

Spirochaetes

In the secondary septicaemic stage of syphilis, spirochaetes invade the liver with production of miliary granulomas.

Fungal Infections

In histoplasmosis the liver is second only to the spleen in frequency of involvement. In the granulomatous form, the lesions are histologically identical with those of sarcoidosis, except for the presence of intracellular fungus in the Kupffer cells. Liver biopsy can be used for diagnosis, both staining for Histoplasma capsulatum and by culture. Histoplasmosis leads to discrete hepatic calcification.

Coccidioidomycosis and blastomycosis also produce sarcoid-like granulomas and the organisms may be demonstrated.

Protozoa

Toxoplasmosis may be associated with granulomas, usually without giant cells [30].

Helminths

The hepatic granulomatous reaction to the Schistosoma ovum is of delayed hypersensitivity type, related to antigen released by the egg. Eggs or their remnants are seen in 94% of liver biopsies. The remnants of eggs are of diagnostic importance.

Toxocara canis is spread by cats and dogs. The second stage can infect the liver of man forming granulomas.

With Fasciola hepatica the clinical picture in the acute stage is of cholangitis with fever, right upper quadrant pain and hepatomegaly. Eosinophilia and raised serum alkaline phosphatase are noted. Hepatic granulomas and ova in the liver may occasionally be seen.

Ascariasis is particularly common in the Far East, India and South Africa. Ova of the round worm Ascaris lumbricoides reach the liver by retrograde passage up the bile ducts. The adult worm may lodge in the common bile duct, producing partial bile duct obstruction and secondary cholangitic abscesses.

Rickettsia

Q fever has predominantly pulmonary manifestations but, occasionally, hepatitis may be prominent and clinically may mimic anicteric viral hepatitis. The granulomas have a characteristic ring of fibrinoid necrosis surrounded by lymphocytes and histiocytes, with a clear space in the centre of the granuloma giving a doughnut appearance.

Viruses

Hepatitis A.

In liver biopsies during the acute hepatitis, occasionally fibrin-ring granulomas may be found.

Hepatitis C.

Epithelioid granulomas are in approximately 10% of surgical transplant liver specimens from patients with hepatitis C-related cirrhosis, less commonly in needle biopsies [31]. Hepatitis B does not do this.

Cytomegalovirus.

Acute infection produces a mononucleosis syndrome. Transient well-formed hepatic granulomas may be associated.

Hepatic Granulomas in the Patient with AIDS (See Chapter 22)

In HIV-AIDS, liver granulomas are frequent and have multiple causes (Table 31.3) [32,33], and these vary geographically and with the concurrent use of antiretroviral agents. Liver biopsy is particularly helpful in showing M. tuberculosis or M. avium-intracellulare. The granulomas tend to be poorly formed without lymphocyte cupping, giant cells or central caseation. Acid-fast bacilli are present in large numbers in clusters of foamy histiocytes or within Kupffer cells. Cytomegalovirus and Herpes simplex infections may also be associated with hepatic granulomas.

Table 31.3. Hepatic granulomas in patients with AIDS

| Infections | Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | |

| Cytomegalovirus | |

| Histoplasmosis | |

| Toxoplasmosis | |

| Cryptococcosis | |

| Neoplasms | Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| Drugs | Sulfonamides |

| Antibiotics | |

| Antifungals | |

| Isoniazid |

Fungal infections may disseminate and initiate granuloma formation. They include Cryptococcus neoformans, histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis and Candida albicans.

Granulomas may also be related to drug therapy. Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole is a common offender, causing granulomatous hepatitis and jaundice. In patients with HIV undergoing treatment there are, of course, many potential drug effects on the liver [34,35].

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a disease of unknown aetiology, characterized by granulomatous lesions involving most organs. Involvement of lungs, lymph nodes, eyes, skin and the neurological system may be associated with well-recognized clinical features, although this is not always so. The liver is frequently affected, although granulomas are often asymptomatic.

Hepatic Histology

Classical sarcoid granulomas are repetitively monotonous, all being at the same stage of development; though small they may coalesce. As the granuloma heals, reticulin fibres are deposited and it is replaced or surrounded by a fibrous reaction (Fig. 31.2). Eventually, the granuloma may disappear or only be seen as a nodule of collagen (Fig. 31.3) or an acellular mass of hyaline material with a fibrous capsule.

Since the hepatic lesions are focal, and fibrosis is restricted to healing lesions, sarcoidosis does not produce the diffuse fibrosis and nodular regeneration of cirrhosis. An association with jaundice and hepatic failure is very rare.

Clinical Features

Overt liver disease is rare. The liver is palpable in only 20% of patients. Occasionally, there is active liver disease with marked hepatic functional abnormalities and liver cell destruction, and fibrosis on liver biopsy [36]. Typically, however, the evidence of hepatic involvement arises not from the clinical picture but from the result of liver biopsy. This shows typical features in about 60% of patients with sarcoid manifestations elsewhere [37,38]. Liver biopsy is indicated as a diagnostic approach when another more accessible tissue, such as lymph gland or skin, is not appropriate.

Biochemical changes—an elevated alkaline phosphatase is the most characteristic liver function test abnormality. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme is increased but not diagnostic.

CT scanning shows discrete upper abdominal lymph node enlargement in about 60% of patients with sarcoidosis. Hepatic CT changes are found only in 38% of those with known hepatic involvement with multiple, small low-attenuation areas on contrast-enhanced scans.

MRI shows multiple, diffuse, densely packed islands of isointense or slightly hyperintense parenchyma on proton density images and corresponding foci of hypointensity on T2-weighted images—contrasting with the hyperintense T2-weighted images characteristic of metastatic or inflammatory disease.

Treatment

In most cases the hepatic involvement does not require treatment—and in any case the response to corticosteroid therapy is poor with little improvement in liver function tests [39]. Improvement seems to be limited to those with mild disease where such improvement in biochemical tests is of doubtful clinical significance. Associated symptoms of sarcoidosis elsewhere in the body, and systemic symptoms such as fatigue, may necessitate treatment.

If there is significant liver disease the following clinical patterns are recognized [40]:

Portal Hypertension.

Young, black people of either sex, appear more susceptible to this manifestation. Portal hypertension is presinusoidal due to portal (zone 1) granulomas. Sinusoidal block may be superimposed due to fibrosis [41]. Rarely, oesophageal bleeding is a real problem. These patients tolerate shunts well. Corticosteroids do not prevent the portal hypertension.

Budd–Chiari Syndrome.

Sarcoidosis has been reported in association with hepatic vein occlusion [42].

Cholestasis.

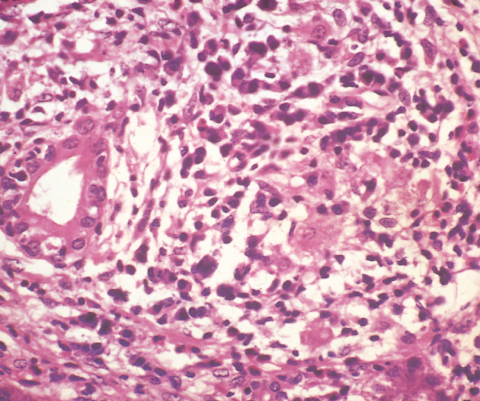

Rarely patients with sarcoidosis, usually male and black, show features of chronic intrahepatic cholestasis. They present with fever, malaise, weight loss, jaundice and usually pruritus. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels are very high and transaminases increased about two to five times. Hepatosplenomegaly is usual. Liver biopsy usually shows granulomas. Portal areas show damaged or even absence of bile ducts [43] (Fig. 31.5). Sequential liver biopsies show relentless progression of the fibrosis and bile duct loss. The prognosis is poor. The patients usually die within 2–18 years from the onset. Corticosteroids are not helpful. Ursodeoxycholic acid may be used to control pruritus. Liver transplantation may be necessary. However, post-transplant multiple hepatic granulomas can recur, but without clinical deterioration [44 ]. The condition may resemble and even be indistinguishable from PBC [45].

Fig. 31.5. Chronic cholestasis in sarcoidosis. A damaged bile duct is surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate including lymphocytes. (H & E, ×160.)

Extrahepatic cholestasis [46] due to bile duct inflammation or portal hilar lymphadenopathy, and diffuse stricturing resembling primary sclerosing cholangitis, or indeed an overlap syndrome, may also occur [47].

‘Granulomatous Hepatitis’

Hepatic granulomas may be associated with a prolonged, febrile syndrome [48,49]. Some patients are eventually diagnosed as having an infection, such as tuberculosis, histoplasmosis or Q fever, or a lymphoma. Those that defy diagnosis are labelled ‘granulomatous hepatitis’. The sufferer is often a middle-aged or elderly male. The granulomas are not widespread. Biochemical tests of liver function are moderately impaired with increases in serum alkaline phosphatase, and slight increases in serum transaminases and globulins. Serum bilirubin is normal. The condition may subside spontaneously or necessitate short- or long-term prednisolone treatment. The ultimate prognosis is excellent [48,50]. Those not responding to, or unwilling to take, corticosteroids may benefit from azathioprine or low-dose, oral pulse methotrexate.

Granulomatous Drug Reactions (See Chapter 24)

Drugs are rare causes of hepatic granulomas, but identification of a granuloma in a liver biopsy should always raise the possibility that it is drug related and not the underlying disease. Typically such granulomas are part of a general hypersensitivity reaction, developing 10 days to 4 months after starting the drug. They may be associated with fever, rash, lymphadenopathy and arthritis.

Serum biochemistry shows increases in alkaline phosphatase and γ-GT. Transaminases may be modestly increased. A rise in serum bilirubin is unusual with a simple granulomatous reaction.

Liver histology shows predominant granulomas. Caseation is absent. Tissue eosinophilia is found in about 70%. Fatty change, portal zone inflammation and bile duct injury are occasionally present. The lesion heals without concentric fibrosis. Such findings with cholestasis should always suggest a drug reaction.

Prognosis is usually excellent with recovery within 6 weeks of withdrawing the drug. Rarely, severe reactions may lead to consideration of corticosteroid therapy.

An enormous number of drugs may be implicated. Drugs that can cause a predominantly granulomatous reaction are listed in Table 31.4. Allopurinol, carbamazepine, glibenclamide and sulphonamides are the most common culprits. Recently, tumour necrosis factor receptor blockers have been added to the list [51]. They are all rare reactions but can be fatal. In all, the histological picture is mixed granulomatous, hepatocellular, cholangitic and vasculitic elements. Carbamazepine and allopurinol are associated with fibrin-ring granulomas [52].

Table 31.4. Important causes of granulomatous drug reactions

| Allopurinol |

| Carbamazepine |

| Diltiazem |

| Glibenclamide |

| Hydralazine |

| Quinidine/quinine |

| Sulfonamides |

Industrial Causes

Beryllium poisoning leads to pulmonary granulomas. Hepatic involvement consists of miliary sarcoid-like granulomas. Pulmonary and hepatic granulomas may be due to inhalation of cement and mica dust, and to copper in vineyard sprayers.

Other Conditions with Hepatic Granulomas

In the early stages of PBC the liver may show widespread hepatic granulomas with a histological picture indistinguishable from sarcoidosis. Whipple’s disease, due to Trophyrema whippelii may be accompanied by hepatic granulomas with bacillary inclusions.

Non-Specific Reticuloendothelial Proliferations: ‘Reactive Hepatitis’

Focal accumulations of mononuclear and epithelioid cells are found in many diseases—perhaps most frequent in viral infections, including infectious mononucleosis, during the recovery phase of viral hepatitis when they contain iron, and in influenza. Occasionally, they are noted in pyogenic infections and septicaemias where polymorphonuclear leucocytes are also present. Their distinction from small sarcoid granulomas may be difficult. If such an accumulation of cells is found in a liver biopsy section, the whole block should be sectioned serially to identify typical granulomas.

Generalized proliferation of Kupffer cells is another frequent finding occurring in infections and in malignant disease.

The Liver in Diabetes Mellitus

Clinical Features

Type 1 Diabetes

There are usually no clinical features referable to the liver. Occasionally, however, the liver is greatly enlarged, firm and with a smooth, tender edge, and this may fluctuate dramatically. Some of the nausea, abdominal pain and vomiting of diabetic ketosis may be due to this. Hepatomegaly is present in around 10% of well-controlled diabetics and in 60% of uncontrolled diabetics. The enlargement is due to increased glycogen. Insulin therapy in the presence of a very high blood sugar level augments the glycogen content of the liver and, in the initial stages of treatment, hepatomegaly may increase.

Type 2 Diabetes

The liver may be enlarged with a firm, smooth, non-tender edge. Enlargement is due to steatosis; the rising incidence of non-alcoholic steatosis and steatohepatitis is well recognized, and Type 2 diabetes is a key feature of the metabolic syndrome that predisposes to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Biochemistry

In well-controlled diabetics, routine tests are usually normal. Acidosis may produce mild changes including hyperglobulinaemia and a slightly raised serum bilirubin level, returning to normal with diabetic control. Eighty per cent of diabetics with fatty liver have abnormal serum biochemical tests—such as transaminases, alkaline phosphatase and γ-GT. Hepatomegaly, whether due to increased amounts of glycogen in type 1 diabetes or to fatty change in type 2, does not correlate with the results of the liver function tests.

Sulphonylurea therapy can be complicated by cholestatic or granulomatous liver disease.

Hepatic Histology

In Type 1 diabetes, histopathology shows normal or increased glycogen in the livers of severe untreated diabetes. Glycogenic infiltration of the liver cell nuclei (Fig. 31.6) appears as vacuolization.

Fig. 31.6. Glycogen infiltration of a hepatic nucleus. Cells contain much glycogen. (Best’s carmine for glycogen, ×1150.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree