It is hard, if not impossible, to envisage management of patients without recourse to liver biopsy, and yet it is a procedure that is often feared by patients, and when done incorrectly can have devastating complications. There is, however, a significant body of evidence to guide the clinician with respect to technique, complications and contraindications.

Selection and Preparation of the Patient

Most biopsies are performed as day case procedures because of patient preference and reduction of costs. The majority of complications occur within 3 h of biopsy, but may occur up to 24 h after the procedure. In 1989, the American Gastroenterological Association and subsequently the British Society of Gastroenterology [5] published consensus statements on out-patient percutaneous liver biopsy, recommending that patients undergoing this procedure should have no conditions that might increase the risk of the biopsy including: encephalopathy, ascites, hepatic failure with severe jaundice or evidence of significant extrahepatic biliary obstruction, significant coagulopathies or serious diseases involving other organs such as severe congestive heart failure or advanced age.

The consensus statements also recommended that the place where the biopsy is performed should have easy access to a laboratory, blood bank and in-patient facilities should the need arise, and there should be staff to observe the patients for 6 h. The patient should be hospitalized if there is any significant complication, including pain requiring more than one dose of analgesic in the 4 h following liver biopsy. The patient should also be able to return easily to the hospital where the biopsy was undertaken within 30 min, and should have a reliable individual to stay with them on the first postbiopsy night. These recommendations are eminently sensible and should form the backbone of any local biopsy policy. Out-patient biopsies should ideally be performed in the early morning so that, should complications occur, the vast majority of patients will be still in hospital.

The method of biopsy is dictated by coagulation indices and indication. Percutaneous biopsies should not be performed if the one-stage prothrombin time is more than 3 s prolonged over control values. Whilst fresh frozen plasma is frequently used to correct coagulation indices, there is little evidence it reduces the risk of haemorrhage [5]. Again, although recombinant factor VIIa can correct prothrombin time, a reduced risk of bleeding has not been shown—in addition, its major drawback is expense.

Evidence-based guidelines on safe platelet thresholds do not exist [5]; in thrombocytopenic patients the risk of haemorrhage depends on the function of the platelets rather than on their numbers. A patient with ‘hypersplenism’ and a platelet count of less than 50 000 is much less likely to bleed than one with leukaemia, who may have a higher platelet count. This distinction particularly arises in patients with haematological problems or after organ transplants where the effects on the bone marrow of cytotoxic therapy, viruses and other infective agents and of possible graft-versus-host reaction may lead to significant abnormalities of platelet function. Alternative techniques to percutaneous biopsy are often used in patients with a platelet count less than 80 000, and some centres 50 000 [5].

Additional risk factors have identified patients with an increased incidence of complications following standard percutaneous biopsy (the alternative techniques are in parentheses): the unco-operative patient (sedation, transvenous or real-time ultrasound-guided), extrahepatic biliary obstruction (real-time ultrasound-guided), ascites (transvenous), cystic lesions (real-time ultrasound-guided), hepatic amyloidosis (transvenous), obesity (transvenous or real-time ultrasound-guided), sickle hepatopathy (transvenous), chronic renal failure (transvenous), and valvular heart disease (consider antibiotic prophylaxis). There is an increased risk of bleeding in patients with malignancy but often these biopsies are real-time ultrasound-guided using thinner needles, with less risk of complications.

All patients being considered for liver biopsy should undergo a prebiopsy ultrasound in order to exclude anatomical variation associated with increased risk of visceral perforation—such as the presence of small bowel between a shrunken liver and the abdominal wall (Chilaiditi’s syndrome), or an intrahepatic gall bladder. Ultrasound also permits the detection of focal lesions such as haemangioma, which may be asymptomatic and may not have been suspected.

Informed Consent

Informed consent should be obtained in writing prior to the biopsy procedure in accordance with individual hospital policies. The consent form should clearly document the morbidity and mortality associated with the route of biopsy, and preferably this should also be documented in the patients notes when the biopsy is initially being discussed, so that the patient can be given sufficient time to refuse the procedure.

Techniques

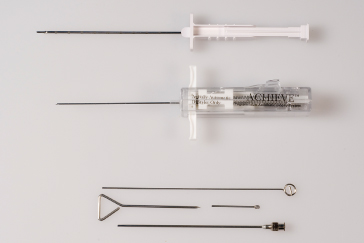

The Menghini needle obtains a specimen by aspiration [6], whilst the sheathed ‘Trucut’ uses a cutting technique (Figs 3.1, 3.2) [7]. Fragmentation of the biopsy is greater with the Menghini method, but the procedure is quicker, easier, has fewer complications [8] and can provide longer specimens in comparison with the standard Trucut specimen [9]. Furthermore, the Menghini needle is cheaper. Pain associated with the procedure is often due to the operator applying insufficient local anaesthetic in the skin, and none in the capsule/ parenchyma. Sufficient 1–2% lignocaine solution should be used.

Fig. 3.1. Three biopsy devices—a standard Trucut needle, an automated Trucut device and a Menghini needle.

Fig. 3.2. (a,b,c) The cutting bevel of the Trucut needle which must be advanced forward, over the tissue in the recession in the needle.

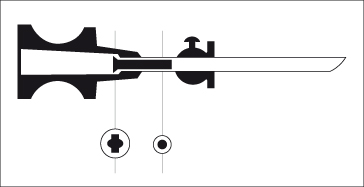

Menghini ‘One Second’ Needle Biopsy (Fig. 3.3).

The 1.4-mm diameter needle is used routinely. A shorter needle is available for paediatric use. The tip of the needle is oblique and slightly convex towards the outside. The needle is fitted within its shaft with a blunt nail. This internal block prevents the biopsy from being fragmented or distorted by violent aspiration into the syringe. The original publication [6] documented a width measured on the slide (fixed tissue) of 0.75 mm using a 15 G needle.

Fig. 3.3. Longitudinal section of the Menghini liver biopsy needle. Note the nail in the shaft of the needle.

Sterile saline (5 mL or more) is drawn into the syringe, which is inserted through the anaesthetized track down to, but not through, the intercostal space. To clear the needle of any skin fragments, 1 to 2 mL of solution are injected. Aspiration is now commenced and maintained. This is the slow part of the procedure. With the patient holding their breath in expiration, the needle is rapidly introduced perpendicularly to the skin into the liver substance and extracted. This is the quick part of the procedure. The tip of the needle is now placed on sterile paper and some of the remaining saline flushed through the needle to deposit the biopsy gently onto the paper. The tissue is transferred into fixative.

Trucut Needle.

This involves a three-stage process, requiring greater operator skill and patient compliance. The patient holds their breath in expiration whilst the needle is advanced along the anaesthetized tract into the parenchyma. The needle tip is then extended, followed by the cutting bevel. To avoid a scissoring action, there needs to be a slight forward force, so that the cutting bevel actually moves forward, slicing liver, as opposed to pulling the needle tip back. This needle results in less fragmentation, and a more reliable specimen in fibrotic livers.

Newer generations of narrower gauge (18 or 20 G) spring loaded Trucut needles require less skill, but are more expensive. The maximum length is determined by the fixed length of the trough in the needle (2 cm) [9].

The intercostal approach is the most frequently used method [8]. Care must be taken to assess the borders of the liver either by percussion or by ultrasound. The liver may be higher than expected (particularly in transplant patients) or lower, such as in patients with chronic lung disease. If there is any doubt with respect to percussion, ultrasound should be used. Some centres use ultrasound at the time of the biopsy in all patients. It does minimize the likelihood of obtaining inadequate specimens, but has not been shown conclusively to reduce major complications [10]. New generation, portable ultrasound equipment is becoming less expensive and the better performance of a liver biopsy can make this cost-effective [11]. In any case, many biopsies are being performed by radiologists who routinely use ultrasound.

If an epigastric mass is present or imaging indicates left lobe disease, an anterior approach is used.

Transjugular (Transvenous Liver Biopsy) [12].

A special Trucut needle (18 or 19 G, Quickcore) is inserted through a catheter placed in the hepatic vein via the jugular vein under fluoroscopic guidance. The needle is then introduced into the liver tissue by transfixing the hepatic venous wall (Fig. 3.4). In patients with advanced liver disease, it has the advantage of facilitating measurement of wedged and free hepatic venous pressure and of opacifying the hepatic vein (Table 3.2). A review of 7000 biopsies [12] indicated that the transjugular technique provided samples of similar quality to those from the percutaneous approach. Biopsies are thinner than with the intercostal technique. Providing four passes are performed, biopsies are adequate to stage chronic viral hepatitis [13,14].

Table 3.2. Indications for transjugular liver biopsy

| Coagulation defects and congenital clotting disorders |

| Acute liver failure pre-transplant |

| Massive ascites |

| Small liver |

| Measurement of hepatic venous pressure gradient |

| Unco-operative patient |

| Severe obesity |

Fig. 3.4. Transvenous liver biopsy. Transvenous liver biopsy. The catheter is in the hepatic vein and the Quick-Core needle is taking the liver biopsy.

Directed (Guided Biopsy).

This involves simultaneous imaging of the lesion in the liver and the advancing biopsy needle tip. Ultrasound is commonly employed, but computed tomography (CT) may be required if the lesion is not visible on ultrasound. Spring-loaded Trucut needles are preferred, and, in patients with poor coagulation, a gel foam plug may be injected through the outer cannula of the Trucut needle after the inner cutting needle, once its contained specimen has been removed [15]. This can be effective in preventing major bleeding.

In chronic liver disease, the blind technique yields sufficient diagnostic material 81% of the time, but this can be raised to 95% if a laparoscopic directed liver biopsy is used [16].

Fine-Needle Guided Biopsy.

Using a 22 G (0.7 mm) needle adds to the safety. It is particularly useful for the diagnosis of focal lesions, although diagnostic accuracy may not be improved [17]. Because of the size, fine-needle biopsy is not so useful in generalized disease such as chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis. Cytological examination of the aspirate is useful for tumour typing [18] and this technique will allow introduction of local therapies such as ethanol or acetic acid.

After Care

Observations should be frequent (quarter hourly for 2 h, half hourly for 2 h and hourly for 2 h) and analgesia should be prescribed [5]. During the puncture the patient may complain of a drawing feeling across the epigastrium. Afterwards some patients have a slight ache in the right side for about 24 h and some complain of pain referred from the diaphragm to the right shoulder—this often indicates a capsular haematoma.

Number of Passes

It has been demonstrated that taking more than one core of liver at biopsy can increase the diagnostic yield [19], but more passes increase the incidence of complications of percutaneous biopsy [8,20,21]. If an adequate specimen is not obtained after two passes, an alternative approach should be employed after a suitable period of observation.

Risks and Complications

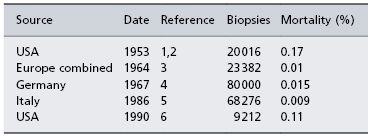

Major and minor complications occur in up to 6% of patients and can be fatal in 0.04 to 0.11% [8,20] (Table 3.3). Major complications of transjugular liver biopsy are reported in 0.6%, with intraperitoneal bleeding in 0.2% due to capsular perforation; mortality is 0.09% [12]. Paediatric cases have higher complication rates with transjugular biopsy [12].

Table 3.3. Fatalities from needle liver biopsy

1 Zamcheck. N. Engl. J. Med. 1953; 249: 1020.

2 Zamcheck. N. Engl. J. Med. 1953; 249: 1062.

3 Thaler. Wien. Klin. Wchschr. 1964; 29: 533.

4 Lindner. Dtsch. Med. Wschr. 1967; 92: 1751.

5 Piccinino. J. Hepatol. 1986; 2: 165 [8].

6 McGill. Gastroenterology 1990; 99: 1396 [20].

Prospective evaluation does not show differences in bleeding between Menghini and Trucut needles [22], but retrospective studies suggest more complications with Trucut needles [8]. No studies have compared the newer (but more expensive) spring loaded Trucut needles (e.g. Temno, Quikcore) with the Menghini needle.

The usual indicators of complications following biopsy are severe pain (either shoulder tip or abdominal) unrelieved by a single injection of pethidine, hypotension and tachycardia. The presence of all or some of the signs should prompt the physician to recommend the patient is observed overnight and if ongoing, investigate and treat. Bleeding may be a life-threatening event, particularly if not detected immediately, so that prompt recognition is essential (see below).

Pleurisy and Perihepatitis

A friction rub caused by fibrinous perihepatitis or pleurisy may be heard on the next day. It is of little consequence and pain subsides with analgesics. A chest X-ray may show a small pneumothorax.

Haemorrhage (Fig. 3.5)

In a series of 9212 biopsies, there were 10 (0.11%) fatal and 22 (0.24%) non-fatal haemorrhages [20]. Malignancy, age, female sex and number of passes were the only predictable factors for bleeding. Bleeding might be related to factors other than clotting diathesis, such as the failure of mechanical compression of the needle tract by elastic tissue [23].

Fig. 3.5. A CT scan showing a bleed following a biopsy. A sharp, white area of contrast is present within the parenchyma of the pseudoaneurysm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree