ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

* Not licensed yet.

Pathology

Changes in the Liver

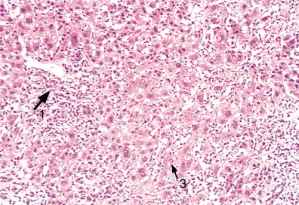

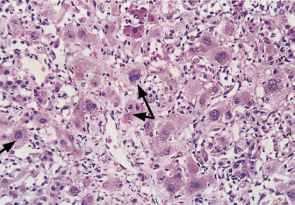

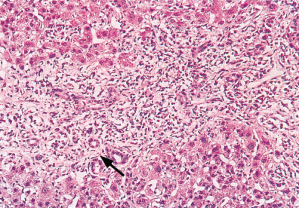

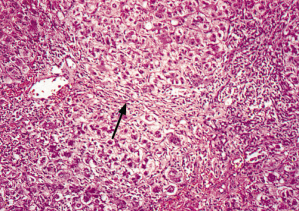

All forms of viral hepatitis have some common histological features. The essential lesion is an acute inflammation of the entire liver [2]. Hepatic cell necrosis is associated with leucocytic infiltration and histiocytic reaction and infiltration. Zone 3 shows the necrosis most markedly and the portal tracts the greatest cellularity (Figs 17.1, 17.2, 17.3). The sinusoids show mononuclear cellular infiltration, polymorphs and eosinophils. Fatty change is rare. Zone 3 liver cells may show eosinophilic change (acidophil bodies), ballooning and giant multinucleated cells may be present. Mitoses are sometimes prominent. Zone 3 cholestasis may be found. Focal ‘spotty’ necrosis may be seen. Bile duct proliferation is usual and damage is an occasional feature [3].

Fig. 17.1. Viral hepatitis: zone 3 (central) (thin arrow) shows marked loss of liver cells. Zone 1 (portal) (thick arrow) shows expansion with cellular infiltration and bile duct proliferation. (H & E, ×40.)

Fig. 17.2. Viral hepatitis: zone 3 shows swollen cells (arrow), mitoses (double arrow) and acidophilic bodies. (H & E, ×80.)

Fig. 17.3. Viral hepatitis: zone 1 (portal tract) shows an acute inflammatory reaction with ductular proliferation (arrow). (H & E, ×50.)

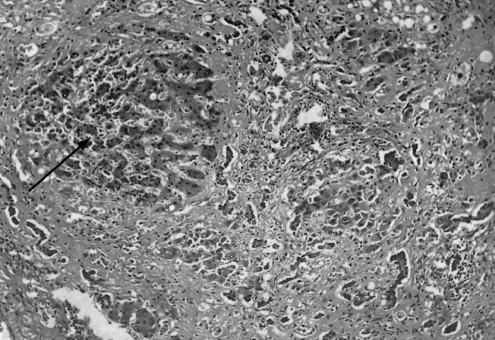

The reticulin network is usually well preserved. Inflammatory cells disappear gradually, and some new zone 1 portal connective tissue can often be found for many months (Fig. 17.4). During recovery reticuloendothelial activity increases throughout. The Kupffer cells contain lipofuscin pigment and iron.

Fig. 17.4. Residual portal zone scarring seen 33 days after the onset of jaundice. (Best’s carmine, ×100). From Sherlock S, Walshe VM [10].

Occasionally, the necrosis may be confluent (submassive), affecting substantial groups of adjacent liver cells, usually in zone 3.

In massive fulminant necrosis the whole acinus is involved. The liver is reduced in size, being smallest in those who die the soonest. Nodular regeneration is seen in those surviving for more than 2 weeks (Fig. 17.5). The cut surface shows a ‘nutmeg’ appearance, red areas of haemorrhage alternating with yellow patches of necrosis.

Fig. 17.5. Acute viral hepatitis. Subacute massive necrosis with nodular regeneration (arrow). (H & E, ×120.)

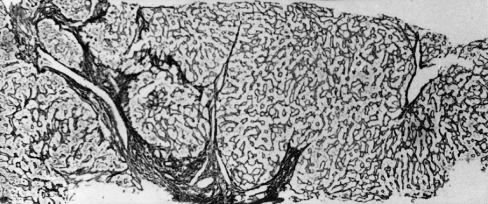

If the necrosis extends from zone 3 to zone 1 the reticulum collapses leaving connective tissue septa. This is termed bridging (Fig. 17.6). This may be followed by the development of active fibrous septa, nodules and cirrhosis in the case of hepatitis B and C. More usually it is followed by scar formation (postnecrotic scarring) (Fig. 17.7).

Fig. 17.6. Acute viral hepatitis. A septum (bridge) has formed between zones 1 and 2 (arrow). (H & E, ×40.)

Fig. 17.7. Postnecrotic scarring. The liver biopsy specimen shows scarring, involving and extending from portal tracts. (Reticulin, ×34.)

Changes in Other Organs

Regional lymph nodes enlarge. Splenomegaly is related to cellular proliferation and venous congestion secondary to increased portal venous pressure as a result of necroinflammatory changes in the liver. The bone marrow is moderately hypoplastic, but maturation is usually normal.

The brain shows an acute non-specific degeneration of ganglion cells. Occasionally, acute pancreatitis and myocarditis have been noted. These changes are rare and only seen in very severe/fulminant cases.

Clinical Types

Acute Hepatitis

Important diagnostic clues can be found in the clinical history. Note is taken of ethnic origin, contacts, recent travel, injections, tattooing, dental treatment, transfusions, sexual preference and ingestion of shellfish. All drugs taken in the previous 2 months are listed.

In general, type A and E hepatitis run the same clinical course often exhibiting a cholestatic phase. Hepatitis B and C may be associated with a serum sickness-like syndrome.

The mildest attack is without symptoms and marked only by a rise in serum transaminase levels. Alternatively, the patient may be anicteric but suffer gastrointestinal and influenza-like symptoms. Such patients are likely to remain undiagnosed unless there is a clear history of exposure. Increasing grades of severity are then encountered, ranging from the icteric, from which recovery is usual, through to fulminant, fatal viral hepatitis.

The usual icteric attack in the adult is marked by a prodromal period, usually about 3 or 4 days, even up to several weeks, during which the patient feels generally unwell, suffers digestive symptoms, particularly anorexia and nausea, and may, in the later stages, have mild pyrexia. An ache or feeling of fullness develops in the right upper abdomen. There is loss of desire to smoke or to drink alcohol. Malaise is profound.

Occasionally, fever and headache may be severe and, in children, its association with neck rigidity may suggest meningitis. Protein and lymphocytes in the cerebrospinal fluid may be raised.

The prodromal period is followed by darkening of the urine and lightening of the faeces. This heralds the development of jaundice and symptoms decrease in severity. Pruritus, indicating a cholestatic phase, may appear transiently for a few days. Persistent vomiting and/or drowsiness or confusion indicate urgent hospital referral because they may reflect worsening liver function and incipient liver failure.

The liver is palpable with a smooth, tender edge in 70% of patients. The spleen is palpable in about 20% of patients. A few vascular spiders may appear transiently.

After an icteric period of about 1–4 weeks the adult patient usually makes an uninterrupted recovery. In children, improvement is particularly rapid and jaundice mild or absent. After apparent recovery, lassitude and fatigue persist for some weeks. Clinical and biochemical recovery is usual within 6 months of onset.

Neurological complications, including the Guillain–Barré syndrome, can complicate all forms of viral hepatitis [4].

Prolonged Cholestasis

Jaundice appears and deepens, and within 3 weeks the patient starts to itch. After the first few weeks the patient feels well and there are no physical signs apart from icterus and slight hepatomegaly. Jaundice persists for 8–29 weeks and recovery is then complete. It is particularly associated with hepatitis A [5] (7.6% in elderly patients) and E (up to 50% of cases). Liver biopsy shows conspicuous cholestasis which tends to mask the definite, usually mild, hepatitis.

This type must be differentiated from surgical obstructive jaundice [5]. Cholestatic drug jaundice is excluded by the history. If doubt remains, ultrasound and liver biopsy are helpful. The need for liver biopsy should be rare.

The prognosis is usually excellent with complete clinical recovery and restitution of a normal liver [6].

Relapses

These occur in 1.8–15% of cases, particularly with hepatitis A infection. In some the original attack is duplicated, usually in a milder form. More often, the relapse is simply shown by an increase in serum transaminases and sometimes bilirubin. Arthritis, vasculitis and cryoglobulinaemia may be present. Multiple episodes may occur, but recovery is usually complete.

Acute Liver Failure (Fulminant Hepatitis)

(See Chapter 5)This rare form of the disease usually overwhelms the patient within 10 days. It may develop so rapidly that jaundice is inconspicuous. More often, the patient, after a typical acute onset, becomes deeply jaundiced. Ominous signs are repeated vomiting, fetor hepaticus, confusion and drowsiness. The ‘flapping’ tremor may be only transient. Coma supervenes rapidly. Temperature rises, jaundice deepens and the liver shrinks. Widespread haemorrhages may develop.

Leucocytosis may be found in contrast to the usual leucopenia of viral hepatitis. The biochemical changes are those of acute liver failure (Chapter 5). The height of the serum bilirubin and transaminase are poor indicators of prognosis. Transaminase levels may actually fall as the patient’s clinical condition worsens. Blood coagulation is grossly deranged and prothrombin and factor V are the best indicators of prognosis.

The time course depends on whether the cause is A, B, C, D, E or non-A-E hepatitis [7]. Fulminant hepatitis is most often associated with viruses A, B/D and E and rarely hepatitis C. In the USA and Europe, fulminant hepatitis may be due to another cause, presumably viral but not yet identified [8].

When hepatitis E occurs in pregnant women a fulminant course is not infrequent.

There are clinical differences in the fulminant course of the three main types [7]. Pyrexia is most frequent with hepatitis A. The duration of illness before encephalopathy is longer with hepatitis non-A-E. The prothrombin time is greatest with hepatitis B. The bad prognosis in those with a longer duration from onset of illness to encephalopathy is probably related to the greater number of non-A-E hepatitis patients in that group. Acute hepatitis A is more likely to run a fulminant course in persons with underlying chronic hepatitis C than B (41 vs. 0%) [9], including those who are not cirrhotic patients.

Posthepatitis Syndrome

Adult patients feel below par for variable periods after acute hepatitis. Usually, this is a matter of weeks but it may extend to months [10]. Features are anxiety, fatigue, failure to regain weight, anorexia and alcohol intolerance, and right upper abdominal discomfort. The liver edge may be palpable and tender.

Treatment consists of reassurance after full investigation. If the acute attack has been type A, chronicity is excluded; if type E, recovery is the normal outcome unless occurring in the context of liver transplantation when viral persistence has been described.

If liver function test abnormalities persist after hepatitis A or E, another cause must be sought. An isolated elevation of unconjugated bilirubin after clinical recovery is usual in patients with coexistence of Gilbert’s syndrome. Persistent transaminase elevation may be due to non-alcohol or alcohol-related steatosis or steatohepatitis, or underlying chronic hepatitis B or C.

Investigations

Urine and Faeces

Conjugated bilirubin appears in the urine before jaundice, giving a brown coloration. Later it disappears although serum levels remain elevated. Urobilinogenuria is found in the late preicteric phase. At the height of the jaundice, very little bilirubin reaches the intestine, so urobilinogen disappears. Its reappearance indicates commencing recovery. The onset of jaundice is marked by lightening of the faeces due to very little bilirubin entering the intestine, resulting in reduced formation of stercobilinogen in the stool. Reappearance of stool colour denotes impending recovery.

Biochemical Changes

Total serum bilirubin levels range widely. Deep jaundice generally implies a prolonged clinical course. An increase in conjugated bilirubin is early, even when the total bilirubin level is still normal.

Serum alkaline phosphatase level is usually less than three times the upper limit of normal and indicates a cholestatic component to the hepatitis, which is fairly common in hepatitis A and E. Serum albumin and globulin are quantitatively unchanged. The serum iron and ferritin levels are raised.

Serum transaminase estimations are useful in early diagnosis, in detecting the anicteric case and for detection of inapparent cases in epidemics. The peak level is found 1 or 2 days before or after onset of jaundice. Later in the course the level falls, even if the clinical condition is worsening. The estimation cannot be used prognostically. Values may remain elevated for 3 to 6 months in those recovering completely.

Haematological Changes

The preicteric stage is marked by leucopenia. These revert towards normal as jaundice appears. Some 5–28% of patients show atypical lymphocytes, resembling those seen in infectious mononucleosis. Acute Coombs’ test-positive haemolytic anaemia is a rare complication. Haemolysis may develop [11], especially in those with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency [12].

Aplastic anaemia is very rare. It appears weeks or months after the acute episode and is particularly severe and irreversible. It is not usually associated with A, B/D, C or E infection and may be due to a hitherto unidentified non-A-E hepatitis.

The prothrombin time is lengthened in the more severe cases and does not return completely to normal with vitamin K therapy.

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is high in the preicteric phase, falls to normal with jaundice and rises again when the jaundice subsides. It returns to normal with complete recovery.

Needle Liver Biopsy

This is rarely indicated in the acute stage. It may be used to diagnose co-existent second pathology, such as steatosis, causing persistent abnormality of liver function tests continuing for more than 6 months after resolution of the clinical hepatitis A or E.

Differential Diagnosis

In the preicteric stage, hepatitis can be confused with other acute infectious diseases, with acute surgical abdomen, especially acute appendicitis, and with acute gastroenteritis. Bile in the urine, tender enlargement of the liver and a rise in serum transaminase values are the most helpful points. Viral markers are essential.

In the icteric stage, the diagnosis must be made from obstructive jaundice. This is outlined in Chapter 11.

The diagnosis of acute viral hepatitis from drug reactions depends largely on the history and then on the serology. There is real advantage in rapid availability of diagnostic tests for HAV and HEV infections which obviates the need for further testing, particularly ultrasound imaging to exclude biliary obstruction and liver biopsy.

Needle liver biopsy is valuable in the problem case. Attempts at a surgical diagnosis are disastrous.

In the posticteric stage, the continuation of transaminase abnormalities necessitates investigations for the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis.

Prognosis

In a survey of 1675 cases of fulminant hepatitis in a group of Boston hospitals, one in eight sufferers from transfusion hepatitis (B and C) succumbed whereas only one in 200 died with type A disease. Since many non-icteric cases are not included in the statistics, the overall mortality rate is undoubtedly very much lower. In the UK, non-A-E hepatitis has the poorest survival [7].

Those who are elderly or in poor general health have a poor prognosis. Fulminant hepatitis is rare in those less than 15 years old. The survival rate is the same for males as for females. The incidence of icteric disease is higher and the prognosis worse in older patients and those with underlying, chronic liver disease.

Treatment

Prevention

Compulsory notification leads to earlier detection and identification of modes of transmission and source of outbreaks, for instance food or water contamination, sexual spread or carriage by blood donors. Vaccination is discussed below.

Treatment of the Acute Attack

Treatment has little effect in altering the course. At the outset this is unpredictable and it is wise to treat all attacks as potentially serious and to recommend adequate rest.

The traditional low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet is popular because it has proved the most palatable to the anorexic patient. Apart from this, no benefit accrues from a rigid insistence upon a low-fat diet. Supplementary vitamins, amino acids and lipotropic agents are not necessary.

Corticosteroids do not accelerate the rate of healing in viral hepatitis: the usual course of hepatitis A and E is towards spontaneous recovery and any benefit of steroids is not sufficient to justify their use, except occasionally in protracted cholestatic hepatitis A. The steroid whitewash improves the morale of both patient and physician but probably has little effect on the healing process.

Patients with severe nausea or vomiting must be hydrated if necessary with intravenous fluids. Those showing signs of acute hepatocellular failure with coagulopathy or encephalopathy require more active measures and the regimen described in Chapter 5 must be instituted.

Follow-Up

The patient should be monitored until symptoms are resolved and liver function tests return to normal. Special attention should be paid to recurrence of jaundice.

Exercise can be undertaken within the limits of fatigue. Alcohol must be denied for 3 to 6 months. Diet can be unrestricted.

Hepatitis A Virus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree