The term ‘secondary sclerosing cholangitis’ is used for a disease where there are similar radiological and histologic features to PSC, but where another cause for the biliary disease can be identified (Table 16.1).

Table 16.1. Causes and mimics of secondary sclerosing cholangitis

| Causes |

| Surgical trauma to bile ducts (with associated cholangitis) |

| Ischaemic injury, e.g. hepatic artery thrombosis after transplantation, or trans arterial chemotherapy, HHT, PVT |

| Bile duct gallstones (may be due to MDR3 mutation) |

| Viral or bacterial infection, e.g. CMV or cryptosporidiosis, severe sepsis |

| Caustic injury, e.g. formalin treatment of hydatid cyst |

| IgG4 associated autoimmune pancreatitis |

| Mimics on cholangiography |

| Malignancy, e.g. metastatic carcinoma |

| Hypereosinophilic syndrome |

| Polycystic liver disease |

| Cystic fibrosis |

| Cirrhosis |

HHT, hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia; PVT, portal vein thrombosis.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Epidemiology

Little is known about the incidence and prevalence of PSC, as good epidemiological studies are extremely difficult to perform.

The true prevalence of PSC associated with IBD is unknown; the estimated prevalence of PSC in patients with ulcerative colitis is 2.5–7.5%. In the USA, based on a prevalence of ulcerative colitis of 40-225 cases per 100000, the prevalence of PSC has been estimated by extrapolation to be two to seven cases per 100 000 population. These figures, however, probably underestimate the actual prevalence of PSC, as the disease can occur in patients with normal serum levels of alkaline phosphatase, and 20–30% of patients with PSC have no associated IBD.

Population studies from the Northern Hemisphere have shown an annual incidence of PSC of 0.9–1.3/100 000 person-years and point prevalence of 8.5–13.6/100 000. This figure appears to be increasing [1–3]. The study from a population in Olmstead County, Minnesota, USA, estimated a prevalence of 20.9 per 100 000 men and 6.3 per 100 000 women. In a similar report from South Wales, UK, the point prevalence was 12.7 cases per 100 000 persons and the annual incidence was calculated at 0.91 cases per 100 000, both very similar to the US data [2].

The higher prevalence of PSC found in more recent studies might be attributed to a more complete capture of incident and prevalent cases, and to a higher rate of liver transplantation among prevalent cases (ascertainment bias). It may not reflect a true increase in prevalence. Also easier access to cholangiography provided by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) scanning may be playing a part.

Small-duct PSC occurs in about 10% of a PSC population (see below). A study in Canada has shown an incidence of small-duct PSC as 0.15/100 000 [4].

Smoking

Cigarette smoking has been recognized as a protective factor against the development of ulcerative colitis. It may also protect against the development of PSC, unlike primary biliary cirrhosis [1]. This protective effect was more marked in patients with PSC than ulcerative colitis, and interestingly was observed in patients with and without IBD. The mechanism of protection in both disorders remains unknown.

Prevalence of IBD in PSC, and PSC in IBD

In Scandinavia, UK and the USA, 70–80% of those with PSC also have coexisting IBD. In reports from Spain, Italy, India and Japan the prevalence of IBD in PSC is 37–50% although very few underwent total colonoscopy and colonic biopsy [5–8].

Conversely, only 2–7.5% of those with IBD have PSC [9]. However, this is very likely to be an underestimate. As pointed out above, patients with PSC proven on radiological imaging may have normal liver biochemical tests.

Both the development of PSC and its outcome are independent of the activity of colitis. PSC may even occur after proctocolectomy. Similarly IBD may present many years after liver transplant for PSC. The natural history of IBD in patients with PSC, although usually involving the whole colon, has a more benign course than in those patients with IBD alone [10].

Colitis associated with PSC may be a separate disease entity as there is a higher prevalence of rectal sparing in those with PSC (52%) than in those with ulcerative colitis alone (6%). Moreover backwash ileitis occurs in 51% of patients with colitis and PSC, versus only 7% for those with colitis alone [11,12].

It is not known why patients with PSC who have undergone pouch surgery for their ulcerative colitis have a higher rate of pouchitis than those without PSC (63 versus 32%) [13]. Likewise, why colonic resection prior to liver transplant eliminates the risk of recurrent PSC is unknown.

Aetiology and Pathogenesis

Immunogenic Factors

It has been suggested that PSC results from a maladaptive immune/ autoimmune response. This hypothesis is supported by the association with specific human leucocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes; polymorphisms of other genes involved in the immune response; autoantibodies in serum; and the link with IBD and the consequent ‘leaking gut’ syndrome [14].

There is an increased frequency of the HLA A1 B8 DR3 DRW 52A haplotype in PSC compared with healthy controls. HLA DR2 and HLA DR6 are also associated with PSC. HLA DR4 appears to be less common in PSC populations and may be protective (Table 16.2).

Table 16.2. Key HLA haplotypes associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) [1,17]

| Haplotype | Association with disease |

| B8-TNF*2-DRB3*0101-DRB1*0301-DQA1*0501-DQB1*0201 | Strong with susceptibility |

| DRB3*0101-DRB1*1301- DQA1*0103-DQB1*0603 | Strong with susceptibility |

| DRB5*0101-DRB1*1501- DQA1*0102-DQB1*0602 | Weak with susceptibility |

| DRB4*0103-DRB1*0401-DQA1*03-DQB1*0302 | Strong with protection against disease |

| MICA*008 | Strong with susceptibility |

There are other genes outside the HLA region that may play a role in the pathogenesis of PSC. Genome-wide association studies are in progress to identify possible susceptibility genes.

No specific autoantigens have been identified in relation to PSC, although smooth muscle antibodies, antinuclear antibodies and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA) are often detected in serum (Table 16.3). A high prevalence of pANCA (33–88%) has been found in patients with PSC, but this autoantibody is not specific to PSC [14]. pANCA is found in ulcerative colitis alone (60–87%), in patients with type I autoimmune hepatitis (50–96%) [15,16] and in primary biliary cirrhosis. Thus it is unlikely that this antibody is involved in the pathogenesis of PSC, and it is not a useful screening test.

Table 16.3. Serum autoantibodies in primary sclerosing cholangitis

| Antibody* | Prevalence (%) |

| Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies | 33–88 |

| Antinuclear antibody | 7–77 |

| Antismooth muscle antibody | 13–20 |

| Antiendothelial cell antibody | 35 |

| Anticardiolipin antibody | 4–66 |

| Thyroperoxidase | 7–16 |

| Thyroglobulin | 4 |

| Rheumatoid factor | 15 |

* Antimitochondrial antibody is only rarely detected in PSC (<1%). This is useful in differentiating primary sclerosing cholangitis from primary biliary cirrhosis.

PSC is associated, in 25% of patients, with other autoimmune conditions such as diabetes mellitus, celiac and autoimmune thyroid disease (Graves’ disease). Rheumatoid arthritis has also been described in association with PSC and may be a clinical marker for those at high risk of rapid progression to cirrhosis [17].

One hypothesis to explain the association between colonic and liver disease is that PSC is mediated by long-lived memory T cells derived from the inflamed gut, which enter the portal circulation and thence reach the liver [14,18]. Aberrant expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules on hepatic endothelial cells may recruit these T cells to the liver. This, in turn, may lead to biliary inflammation, fibrosis and bile duct stricturing.

Infections

Potentially, infectious agents could lead to the development of PSC but to date there is no secure evidence for any of the putative infectious agent studied, including viruses and parasites.

The association of PSC with IBD led to the hypothesis that colonic bacteria plus activated lymphocytes enter the portal circulation through a leaky diseased mucosa [14,18]. Chemokines and cytokines released from within the liver attract macrophages/ monocytes, lymphocytes, activated neutrophils and fibroblasts to the site of inflammation. In genetically susceptible individuals, bacterial antigens may act as molecular mimics and cause an immune reaction responsible for initiating PSC.

Clinical Features

Nowadays, most individuals with PSC are asymptomatic. Symptoms, when present, are non-specific and relate to cholestasis, for example pruritus, right upper abdominal quadrant pain, fatigue and weight loss. In a few, episodes of fever and chills are predominant. A minority present for the first time with decompensated cirrhosis and portal hypertension, that is ascites and variceal haemorrhage. Nevertheless, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly are the most frequent abnormal physical findings on clinical examination at the time of diagnosis.

Osteopenic bone disease is both a complication of advanced PSC and IBD. Steatorrhoea and malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins occur only with prolonged cholestasis with jaundice. Presentation with jaundice is uncommon and it is often associated with the presence of underlying cholangocarcinoma. IgG4-associated sclerosing cholangitis often presents with jaundice, and should be actively excluded by serology and/or histological assessment.

Diagnosis

Laboratory Investigations

The finding of cholestatic liver biochemistries, an elevated alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, in an asymptomatic individual with IBD is suggestive of PSC. Blood tests typically fluctuate over time and some may even return completely to normal.

Autoantibody tests (see above) are of little diagnostic significance. IgM concentrations are increased in about 50% of patients with advanced PSC. The IgG4 level should be measured in all patients with suspected PSC; raised levels are detected in about 10% and associated with a worse outcome if left unrecognized and thus untreated [19].

Radiological Features

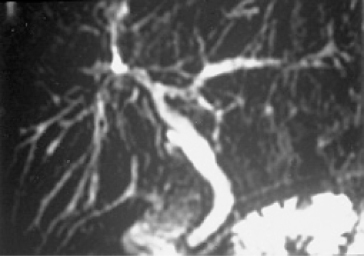

The diagnosis of PSC depends on typical abnormalities shown on cholangiography. These are diffuse stricturing of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts with dilatation of the areas between strictures, causing a ‘beaded’ appearance of the biliary tree. MRCP is the investigation of choice over endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (Fig. 16.2). MRCP is non-invasive, does not involve radiation and is comparable to ERCP for diagnosis of PSC with good interobserver agreement [20–22]. ERCP should be reserved for either therapeutic purposes or to facilitate diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma in those with ‘suspicious’ lesions on MRCP. ERCP may still have a place in patients where the diagnosis remains uncertain after MRCP. Note that the cholangiographic characteristics can be identical in secondary sclerosing cholangitis, and the clinician should be alert to this possibility, even though unusual.

Fig. 16.2. Magnetic resonance cholangiogram showing multiple stricturing and dilatation, the typical changes of sclerosing cholangitis.

Histology

Histological examination of the liver is not required to make a diagnosis of primary or secondary cholangitis if the radiological findings show the typical changes described above.

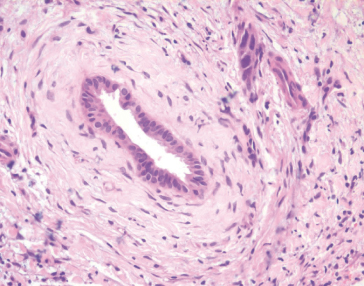

The characteristic early pathological findings of PSC are periductal ‘onion-skin’ fibrosis and inflammation, with portal oedema and bile ductular proliferation resulting in expansion of portal tracts (Fig. 16.3). The early changes of any cause of sclerosing cholangitis may be focal and non-specific. Later, the fibrotic process progresses, leading to the end-stage of biliary cirrhosis. The severity of fibrosis, however, varies throughout the liver and thus ‘staging’ degree of fibrosis with liver biopsy is very unreliable [23]. In advanced cases, loss of bile ducts can lead to a ‘vanishing bile duct syndrome’. Histology is diagnostic in only one–third, although in another third there may be findings suggestive of biliary disease. Patients with small-duct sclerosing cholangitis have normal cholangiograms with characteristic liver histology of PSC.

Fig. 16.3. Histology: liver biopsy showing ‘onion skin’ periductal fibrosis, typical of sclerosing cholangitis.

Colonoscopy

Since coexisting IBD may be asymptomatic, all patients given a diagnosis of PSC and not already known to have IBD should undergo colonoscopy with multiple biopsies.

Special Populations

Small-Duct PSC

Patients who have cholestatic liver biochemistries and features consistent with a diagnosis of sclerosing cholangitis on liver biopsy, but who have a normal cholangiogram, are described as having small-duct PSC. Of the PSC population 6–16% have small-duct disease [24–26]. For the most part, the course of their disease is milder than for large-duct disease. There is a more favourable prognosis with regard to patient survival, need for transplantation and the development of cholangiocarcinoma. To date, no cases of cholangiocarcinoma have been reported in association with small-duct disease. Over a 10-year follow-up, a quarter of these patients develop typical changes of large-duct PSC on cholangiography [27–31].

Autoimmune Hepatitis and Sclerosing Cholangitis

Patients with simultaneous or sequential PSC and autoimmune hepatitis have been described [32,33]. This has been reported more often in children than adults. Overlap should be considered if the transaminases are greater than twice the upper limit of normal and the serum IgG is elevated. Liver histology will show the diagnostic feature of prominent interface hepatitis. Immunosuppression, particularly in children, appears to be helpful [19,34,35].

IgG4-Associated Cholangitis

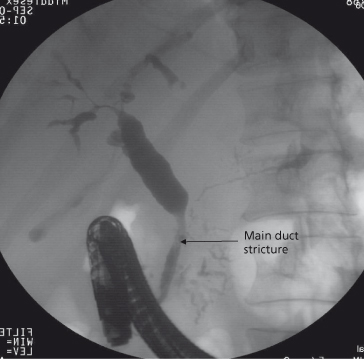

IgG4 associated disease is a multisystem disorder which may involve the pancreas, kidneys, lungs, thyroid, retroperitoneal lymph nodes, salivary glands and aorta. Some patients with IgG4 associated autoimmune pancreatitis have biliary strictures. These are often distal but may involve the entire biliary tree similar to PSC (IgG4-associated cholangiography) (Fig. 16.4) [36]. In this male-predominant disease, serum IgG4 levels are variably increased. Importantly, the disease is responsive to steroids. A retrospective study has shown elevated IgG4 levels in a small (9%) proportion of patients with PSC. This untreated subgroup appear to have a more severe disease course with higher bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase, and shorter time to transplant, than PSC patients with a normal IgG4 level. It is possible that these patients really have IgG4-associated systemic disease and therefore may respond to corticosteroid therapy, but this needs further study [19].

Fig. 16.4. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram showing long distal biliary stricture (arrow) with intrahepatic stricturing and dilatation, the typical appearance of IgG4 associated cholangitis.

Management of Complications

The management of the non-hepatic complications of cholestasis that may occur in PSC (pruritus, fatigue and osteoporosis) are discussed elsewhere (see Chapter 11).

Dysplasia and Cancer

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree