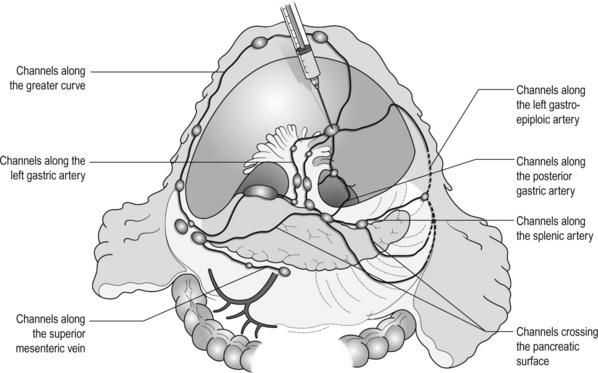

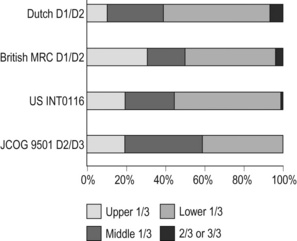

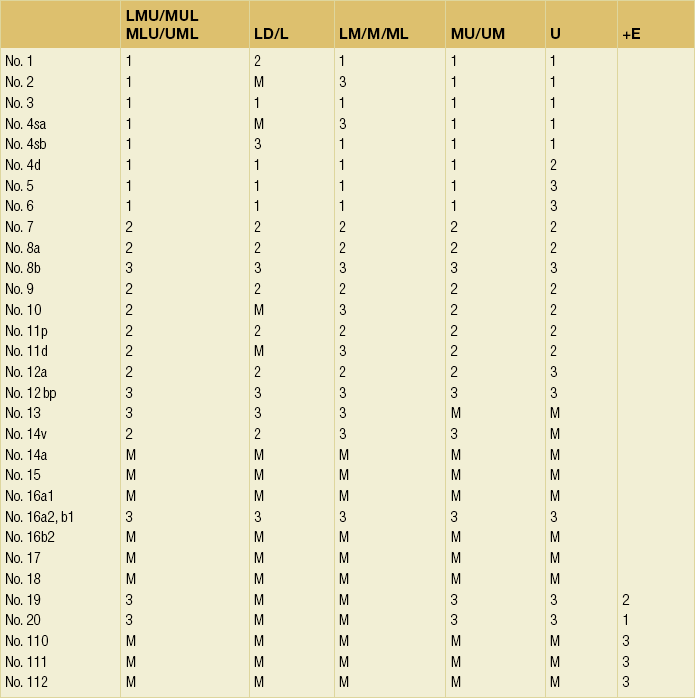

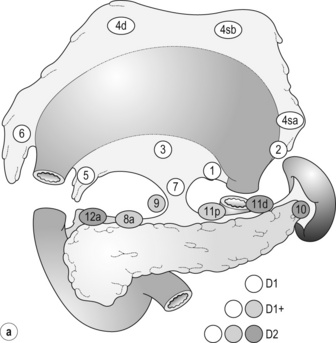

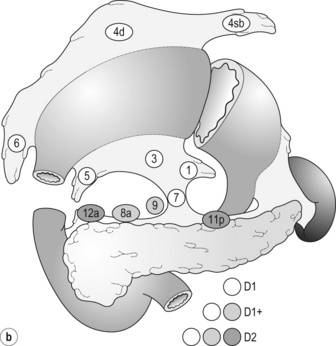

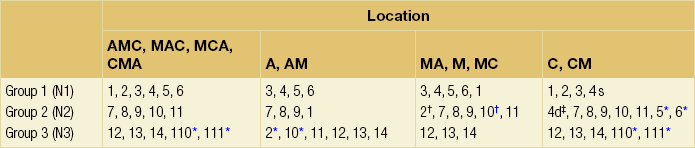

7 In addition, it should be noted that the patterns of failure after gastric cancer surgery have been variously reported using similar classifications but with different definitions. An example is shown in Table 7.1: hepatic and lymph node recurrences are categorised as distant and local failure respectively in the Dutch D1/D2 trial,1,2 but as regional failure in the Intergroup 0116 study.3 Table 7.1 Different definitions of patterns of failure in the Dutch and American trials on gastric cancer surgery Lymphatic spread is the most common mode of dissemination in gastric cancer. Lymph node metastasis is histologically proven in 10% of T1 tumours, and the rate increases as the invasion deepens, up to 80% of T4a tumours.4,5 The lymphatic drainage system from the stomach has been well demonstrated in lymphography studies (Fig. 7.1). Unlike other parts of the digestive tract, the stomach has multidimensional mesenteries that contain dense lymphatic networks. Cancer cells can flow out of the stomach through any of these routes and by way of the nearby perigastric nodes, to reach the nodes around the coeliac artery. They then enter the para-aortic nodes and finally flow into the thoracic duct and systemic circulation. Systemic metastasis can occur via this route. In particular, bone marrow carcinomatosis occurs most frequently in cases with extensive nodal disease.6,7 The stomach has the largest number of ‘regional lymph nodes’ of any organ in the human body. After a total gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy, more than 40 lymph nodes can usually be collected with careful retrieval. Of the malignant tumours listed in the UICC/TNM classification,8 stomach cancer requires the largest number of nodes to be removed as a minimal requirement to allow a pN0 diagnosis (16 nodes) and the largest number of positive nodes for the highest N category (pN3b, 16 or more positive nodes).This suggests that lymphatic metastasis from gastric cancer may remain in the dense lymphatic filters for some time and that patients with nodal metastasis can still be cured by adequate dissection. Peritoneal metastasis is the most common type of failure after radical surgery for gastric cancer.9 Once the tumour penetrates the serosal surface (T4a), cancer cells may be scattered in the peritoneal space. They can be implanted in the gastric bed or any part of the peritoneal cavity and subsequently cause intestinal obstruction or ascites. Peritoneal metastasis is much more common in diffuse-type cancers than the intestinal type10 and later causes peritonitis carcinomatosa, a characteristic recurrent pattern of gastric cancer, which is relatively uncommon in colorectal adenocarcinomas that are mostly of the intestinal type. Peritoneal lavage cytology is a sensitive test for this metastasis. Almost all patients with positive cytology subsequently develop peritoneal recurrence even after macroscopically curative surgery. In the UICC/TNM 7th edition,8 positive cytology (‘cy+’) has been included in the definition of pM1. Peritoneal metastasis is refractory to systemic chemotherapy. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy with or without hyperthermia is being vigorously tested in various centres. Some promising results have been reported,11 but the evidence is not yet compelling. Liver metastasis is relatively uncommon at the time of diagnosis of gastric cancer, but is commonly seen as a part of systemic failure. In the 15-year follow-up report of the Dutch D1/D2 trial, liver metastasis was found, either as the sole site or with other sites in 102 of 319 deaths with recurrence.12 It occurs predominantly in intestinal-type tumours. Unlike in colorectal cancer, liver metastasis from gastric cancer is usually multiple and associated with other modes of spread. Resection is rarely indicated and, even if it is carried out, the prognosis is poor. Gastric cancer penetrating the serosa sometimes extends to the adjacent organs or structures. When the operation is potentially curative, these may be excised en bloc with the stomach. It is of note that, in a considerable proportion of apparent T4b cases, pathological assessment shows only inflammatory adhesion without direct tumour invasion.13 Even serosa-negative tumours can recur in the peritoneal cavity after surgery. These cases are usually associated with lymph node metastasis. A possible explanation for this is that during lymph node dissection lymphatic channels were broken and cancer cells in the lymph nodes spilled out. This was proven in a unique study from Korea,14 though it has not been confirmed whether these spilled cells are implanted and grow. These intraoperative spillages of cancer cells might be prevented by careful non-touch isolation techniques and/or by use of clips or vessel-sealing devices. However, the simplest means to prevent cancer cell implantation during surgery will be peritoneal wash with a large volume of saline before abdominal closure. A small-scale randomised study showed a significant survival benefit of extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage (EIPL) in gastric cancer patients with positive cytology.15 The incidence of gastric cancer in Japan is among the highest in the world. Approximately 100 000 new cases are diagnosed every year, accounting for 11% of all cases in the world.16 The age- standardised incidence, however, has been rapidly decreasing as in other countries in the world, probably due to the decreasing infection of Helicobacter pylori. The peak incidence was in the 1950s (male 71, female 37 per 105 population), the time when the mass screening programme was planned and the basic style of radical D2 gastrectomy was proposed (for reference, the incidences in 2010 were 12.4 and 7.1 respectively). The Japanese documentation system and excellent treatment results influenced the Western concept of radical surgery for gastric cancer. Some surgeons visited Japanese institutions to convince themselves of the feasibility and efficacy of the technique and have successfully reproduced the results in the West.17,18 However, most non-specialist surgeons could not overcome their scepticism and were reluctant to practise this aggressive surgery in their patients. An important obstacle is the difficulty in directly comparing the results between Japan and the West due to the following two issues. A hypothesis that gastric cancer in the West may be a different disease to that in Japan prevails and prevents positive discussion to advance optimal treatment for gastric cancer patients on a global level. In the studies biologically analysing and comparing surgical specimens, no evidence has been shown to support the hypothesis.19,20 The following are the currently discussed differences. Proximal location: It has been repeatedly highlighted that Western gastric cancers are predominantly located in the proximal stomach while Japanese tumours are found mostly in the distal stomach. This might suggest that these are different diseases. However, this needs careful consideration. Adenocarcinoma of the lower oesophagus and the oesophagogastric junction is one of the most rapidly increasing malignant tumours in the West, especially among white males.21 This trend, together with the rapid decrease of distal gastric cancers, makes it plausible that Western gastric cancer arises mostly in the proximal stomach. However, the lower oesophageal adenocarcinoma is a new, distinct disease with a different aetiology and contrasting patient backgrounds,22 and therefore should be considered separately from ‘classical’ gastric cancer. In the three large-scale Western surgical trials, the Dutch D1/D2,1 the British MRC D1/D223 and United States INT0116 studies,3 the proportion of proximal third tumours was 10.3%, 30.5% and 19.5% respectively, and was not significantly different from that (19.1%) in the Japanese D2/D3 study24 (Fig. 7.2). This suggests that, as far as surgically targeted gastric cancers are concerned, tumour location is not largely different between the West and Japan. The apparent predominance of proximal tumours in the West may be a simple reflection of the mixture of different diseases, i.e. increasing oesophageal and decreasing gastric adenocarcinomas. Patient factor: Western patients with gastric cancer are on average 10 years older, much more likely to be obese and more frequently have comorbidities, especially of cardiovascular diseases, than their Japanese counterparts.25 Although this does not mean that the disease is different, it certainly affects surgical process and outcomes. In particular, obesity hampers the completion of extended lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer, even in specialist Japanese centres. It has been shown to be an independent risk factor for postoperative morbidity.26 Due to the decreased incidence and the technically demanding therapeutic requirements, gastric cancer in the West is today considered as a disease that should be treated in specialist centres. Several studies have shown relationships between the hospital/surgeon volume of gastric cancer treatment and operative mortality.27 Given the accelerated ‘proximal shift’ of the disease and the increasing surgical risks in Western patients, the trend of centralisation will further progress. Proximal resection margin is the main determinant in selecting a total or distal gastrectomy. During surgery for T2 or deeper tumours, the resection line should be determined with a sufficient margin from the palpable edge of the tumour. A 5-cm margin has traditionally been recommended.30 In some guidelines, even 8 cm is recommended for diffuse-type tumours,31 but this would necessitate most tumours of the gastric body requiring a total gastrectomy or oesophagogastrectomy. Common types of gastrectomy for gastric cancer are as follows. Total gastrectomy: This involves removal of the whole stomach including the cardia (oesophagogastric junction) and the pylorus. It is indicated for tumours arising at or invading the proximal stomach. Distal (subtotal) gastrectomy: This involves removal of the stomach including the pylorus but preserving the cardia. Two-thirds or more of the stomach is usually removed for gastric cancer. It is indicated for middle or lower third tumours with sufficient resection margins mentioned above. Proximal gastrectomy: This involves removal of the stomach including the cardia but preserving the pylorus. It is indicated for proximal tumours with or without oesophageal invasion, where more than half of the distal stomach can be preserved. Other resections for T1 tumours: Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG) is indicated for T1 tumours in the gastric body having negligible possibility of metastasis to the peripyloric lymph nodes. About a 3-cm pyloric cuff with the right gastric artery is preserved. Total gastrectomy ‘de principe’ for distal cancers: Some European surgeons have argued that all cancers of the stomach, even those in the distal third, should be treated by total gastrectomy. This principle is based on the experience of frequent involvement of proximal resection margin and consequent anastomotic local recurrence. Theoretically, total gastrectomy ensures more certain negative margins and sufficient lymphadenectomy. In addition, the possible occurrence of multicentric cancer in the gastric stump can be prevented. On the other hand, total gastrectomy is associated with a higher operative morbidity and mortality, increased risk of long-term nutritional problems and impaired quality of life as compared to distal gastrectomy. The policy of total gastrectomy de principe should be abandoned for the following reasons: 1. Provided the rules on safe margins of resection listed above are adhered to, a positive proximal resection margin is rare. If the margins are still positive, this usually indicates an aggressive and extensive malignancy and the resection line involvement will not be a major determinant of prognosis. 2. The lymph nodes that can be removed only by total gastrectomy, station nos. 2 (left cardia), 4sa (upper greater curve), 10 (splenic hilum) and 11d (distal splenic artery), are seldom involved in distal gastric cancers. If they are involved, again this indicates an aggressive malignancy and extended surgery would not alter survival outcome. 3. The incidence of second primary cancer in the gastric stump is low. Long-term surveillance by endoscopy may detect a new lesion that can be removed by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Lymph node metastasis is the most common mode of spread in gastric cancer. Histological nodal metastasis has been proven in 80% of T4a/T4b tumours, and even T1 tumours have a 10% probability of lymph node metastasis (T1a 3%, T1b 18%).4,5 Unlike hepatic and other distant metastases, lymph node metastasis from gastric cancer can be surgically removed for potential cure as long as it is confined to the regional area.The optimal extent of lymphadenectomy, however, has been controversial. Japanese surgeons and pathologists have extensively investigated the distribution of lymph node metastasis. They have recorded it using standardised anatomical station numbers (Fig. 7.3). They then classified the stations into three groups, basically according to the incidence of metastasis (N groups 1–3). As the pattern of lymph node metastasis varies with the location of the primary tumour, N groups 1–3 were separately defined depending on the primary tumour location. These numbers of nodal groups were also used to express the grade of nodal disease (N1–3) and the extent of lymphadenectomy (D1–3), e.g. cancer with metastasis to a node in the second group was designated as N2, and complete dissection of up to the second group nodes was defined as D2. Figure 7.3 Station numbers of lymph nodes around the stomach. Modified from the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma, 3rd English edn.39 ACM, A. colica media; AGB, Aa. gastrica breves; AGES, A. gastroepiploica sinistra; AHC, A. hepatica communis; AJ, A. jejunalis; APIS, A. phrenic inferior sinistra; TGC, truncus gastrocolicus; VCD, V. colica dextra; VCDA, V. colica dextra accessoria; VCM: V. colica media; VGED, V. vastroepiploica dextra; VJ:V. jejunalis; VL, V. lienalis; VMS, V. mesenterica superior; VP, V. portae; VPDSA, V. pancreaticoduodenalis inferior anterior. Since its first edition published in 1962, the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma (JCGC) has undergone periodic revisions, and each time the definitions of the lymph node groups have been slightly modified. The Dutch and MRC D1/D2 trials were conducted using the N and D (‘R’ at that time) definitions of the 11th edition of the JCGC34 (Table 7.2), while the Taipei D1/D3 trial35 and the Japanese D2/D3 trial24 used the 12th edition,36 in which the lymph nodes were grouped from N1 to N4. In the 13th edition,37 the nodal grouping was completed, with four groups (N1–3 and ‘M’) in five categories of the primary tumour location (Table 7.3). This definition was based on the ‘dissection efficiency index’ of each lymph node station,38 calculated using the incidence of metastasis and survival data of a large number of patients. As compared to the 11th edition, D2 lymphadenectomy defined in the 13th edition required more extensive dissection, e.g. for distal third tumours, station nos. 11p, 12a and 14v were included as N2 nodes. Table 7.2 Lymph node groups used in the Dutch and MRC D1/D2 trials (Japanese classification, 11th edn) A, lower third; M, middle third; C, upper third. *Resection or non-resection of these nodes does not affect the D number. †These nodes should be excised if the primary tumour site is the MC. If the primary tumour site is MA or M, removal is optional. ‡In proximal gastrectomy, non-resection of these nodes does not affect the D number. Outside Japan, it is widely believed that Japanese N1 nodes are perigastric and N2 nodes are those along the coeliac artery and its branches. Although this expression roughly reflects the nodal groups, it is apparently incorrect in terms of the original concept of grouping based on the primary tumour location. The misunderstanding seems to be due to the over-complicated definitions of the JCGC. In the latest 14th edition (third English edition39), the traditional nodal grouping system has been abandoned, and the simplified ‘D’ has been defined according to the type of gastrectomy (Fig. 7.4). The new ‘D’ definitions in the Japanese Treatment Guidelines32 are simple, practical and mostly compatible with those in the 13th edition, with only some exceptions. D1, D1 + and D2 (D3 is no longer included) are defined for the two major types of gastrectomy, total and distal, regardless of the tumour location. It should be noted that the lymph nodes along the left gastric artery (no. 7), which used to be classified as N2 for tumours in any location, are now included in the D1 category for any type of gastrectomy. This is based not only on the previously mentioned efficacy index analysis, but also on the view that surgery for gastric carcinoma should as a minimum include the division of the left gastric artery at its origin. In Japan, the benefits of D2 over less extensive dissections have never been tested in a randomised study. Instead, D2 was compared with more extensive surgery, D2 plus para-aortic nodal dissection (PAND), in a well-designed, multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT).24 This confirmed that D2 and D2 + PAND were performed with low operative mortality (0.8%) by specialist surgeons,40 but failed to show a survival benefit of PAND. They have abandoned this super-extended lymphadenectomy as a means of prophylaxis, but they still never consider that D2 may not be superior to D1. A single institutional RCT in Taipei showed a significant survival benefit of D2/3 over D1,35 and this is so far the only RCT that showed superiority of extended lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer. In these trials, total gastrectomy in the D2 arm was performed with pancreatosplenectomy, which caused high morbidity and mortality. Despite these negative results for D2, the Dutch group continued the follow-up of the patients for 15 years and finally published remarkable results.12 They compared the recurrence of gastric cancer in both arms on the basis of autopsy findings and found a significantly lower rate of gastric cancer death in D2 than in D1 patients. They concluded the study by stating that D2 should be performed as potentially curative surgery for gastric cancer. In the Western literature, the definition of extent of lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer is often ambiguous. The number of retrieved lymph nodes is sometimes used as a surrogate for ‘D’, e.g. extended lymphadenectomy means retrieval of 25 or more nodes.41 This is a useful method to retrospectively assess the volume of lymphadenectomy in a gastrectomy where anatomical information of dissected lymph nodes is unavailable. 1. Who picked up the nodes from which condition of the specimen for what goal. More nodes are retrieved when a surgeon tries to pick up as many nodes as possible in a fresh specimen than when a pathologist picks up swollen nodes from a formalin-fixed specimen up to the minimal requirement number. 2. Disease stage. In advanced disease with multiple lymph node metastases, the nodes are hard and easily recognised, even if they are small. 3. Patient factor. In obese patients, the lymph nodes are not easily recognised. Proximal gastric cancer may metastasise to the splenic hilar nodes (no. 10) via the gastrosplenic ligament (no. 4sa) and/or the left gastroepiploic lymphatics (no. 4sb). The incidence of no. 10 metastasis increases up to 25–30% when the tumour invades the greater curvature of the upper gastric body.38 These can be completely cleared by splenectomy, and up to 25% of the patients having positive no. 10 nodes survive more than 5 years. Total gastrectomy with splenectomy can be performed by specialist surgeons without increasing mortality.40 In this situation the author advocates gastrectomy with splenectomy. Although a number of observational studies have demonstrated a lack of survival benefit or even a negative prognostic effect of splenectomy,43,44 these are all heavily biased, retrospective comparisons and cannot advocate spleen preservation. Medium-sized RCTs were conducted in Chile46 (N = 187) and Korea47 (N = 207) to compare total gastrectomy (TG) and TG + splenectomy (TGS). In both studies, TGS did not increase operative mortality by experienced surgeons, and although the 5-year survival rate of TGS was higher than that of TG, the difference was not statistically significant. They concluded that splenectomy was not justified. These are negative studies, but are still unconvincing. In a multicentre RCT conducted in Japan,48 503 patients with proximal gastric cancer were randomised to receive TG or TGS during a curative operation, and are currently being followed up until the final survival analysis with complete 5-year results, which is scheduled in 2014. The TGS showed higher operative morbidity (23.6%) than TG (16.7%), but similar mortality (0.4% vs. 0.8%).49

Surgery for cancer of the stomach

Modes of spread and areas of potential failure after gastric cancer surgery

Pattern of failure

Dutch D1/D2 trial1,2

US Intergroup 01163

Local

Gastric bed, anastomosis, regional lymph nodes

Gastric bed, anastomosis, residual stomach

Regional

Peritoneal carcinomatosa

Liver, lymph nodes, peritoneal carcinomatosa

Distant

Liver, lung, ovary and other organs

Outside the peritoneal cavity

Metastatic pathway

Peritoneal spread

Haematogenous spread

Direct extension

Intraoperative spillage

The concept of radical gastric cancer surgery

Gastric cancer surgery in Japan

Development of gastric cancer surgery in the West

Different disease hypotheses

Role of radical surgery in Western practice

Principles of radical gastric cancer surgery

Resection margins

Type of gastrectomy

Lymphadenectomy

Lymph node groups in the former Japanese classifications

New definition of lymphadenectomy

D2 lymphadenectomy – evidence

Number of lymph nodes and extent of lymphadenectomy

Splenectomy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Surgery for cancer of the stomach