Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a highly prevalent disorder characterized by nonspecific symptoms that can mimic other common medical conditions. A careful history and physical examination may reveal clues that suggest a coexisting or alternative diagnosis, such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth or celiac disease (CD). Testing for bacterial overgrowth has limitations, but emerging data suggest that antibiotics may be of some benefit in patients with IBS with diarrhea and bloating. CD seems to have a higher prevalence in patients with IBS. Some patients with IBS may have symptomatic improvement on gluten-restricted diets, without histologic or serologic evidence of CD.

A 33-year-old woman presents for a second opinion after recently being diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) by her primary care physician. She never had gastrointestinal problems until going on a vacation to South America 2 years ago. During the trip, both she and her husband had an episode of food poisoning from which he recovered uneventfully within several days. However, since that time she has had persistent abdominal cramping, bloating, and intermittent episodes of diarrhea. After reading about IBS on the Internet, she altered her diet to include more fresh fruits and vegetables and began taking fiber supplements. Despite these dietary modifications, she has had little symptomatic improvement. Her medical history is notable for 2 miscarriages and anemia. In your office her physical examination is normal, and the results of a recently ordered complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel are normal except for a mildly elevated mean corpuscular volume. Does this patient have IBS, or are there clues in her presentation to suggest an alternative or coexisting diagnosis, such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) or Celiac disease (CD)? How do we best approach this case?

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic gastrointestinal (GI) tract disorder of unknown origin characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits in the absence of detectable biochemical or structural abnormalities. IBS is one of the most common functional GI disorders with an estimated prevalence of 10% to 15% in Western adult populations. Although only a minority of patients with IBS seek medical care, they account for a large percentage of referrals to gastroenterologists and use a substantial portion of health care resources. Direct and indirect costs of IBS are staggering, reaching up to $30 billion per annum in the United States alone.

IBS occurs in both genders; however, women are affected roughly in the ratio of 2:1 and tend to seek medical care more often than men. The onset of symptoms occurs most frequently before the age of 50 years; however, all ages are affected and symptoms can persist well into advancing years. IBS is commonly subdivided into different phenotypes depending on the most prevalent bowel habit: diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D), constipation predominant (IBS-C), and mixed features (IBS-M). The prevalence of each subtype has been shown to vary in different studies, but overall, IBS-D or IBS-M may be slightly more common. Comorbid symptoms and disorders are common with IBS, particularly in patients with severe symptoms and those seen in referral practices. Psychiatric comorbidities are estimated to occur in about 60% of patients with IBS presenting to gastroenterology clinics and in up to 70% of those seen in tertiary referral centers. Health-related quality-of-life scores are lower in patients with IBS than healthy controls and are similar to other chronic medical disorders, such as asthma, gastroesophageal reflux, and end-stage renal disease.

The pathophysiology of IBS is incompletely understood, although it is considered to be a multifactorial disorder arising from dysregulation in the brain-gut axis as well as interactions between genetics, motor and sensory dysfunction, dysregulated intestinal immunity, and psychosocial abnormalities. Recent data suggest that patients with IBS may have increased hydrogen gas production in their small bowel. This observation has led some clinicians to hypothesize a role for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) in the pathogenesis of IBS and propose treating patients with antibiotics, especially those with symptoms of bloating and diarrhea. Although still controversial, this approach is gaining popularity and at present is the subject of much research and debate. Postinfectious IBS (PI-IBS) is a well-described subtype of IBS that can present de novo following a bacterial or viral gastroenteritis. It tends to occur more often in women and with time, usually develops into an IBS-D phenotype. Although a recent study concluded that PI-IBS likely accounts for only a small subset of IBS cases, its existence argues for a strong association between environmental triggers and intestinal inflammation in the development of symptoms in certain at-risk individuals.

On further questioning, it was found that our patient’s bloating and diarrhea is generally worse following meals and seems to be particularly bad after consuming dairy products. She is always fatigued and has gained 20 pounds (9 kg) since the onset of her symptoms. She denies any rectal bleeding and has no family history of colorectal cancer. At this point, do we have enough information to diagnose her with IBS? What additional studies, if any, should be performed?

Diagnosing IBS

In clinical practice, IBS symptoms are often heterogeneous and can masquerade as several other medical conditions. Because of this ambiguity, it is common for both general practitioners and gastroenterologists to order an array of expensive and invasive tests before the correct diagnosis is eventually made. National guidelines discourage this approach and recommend using clinical grounds to diagnose IBS without pursuing an exhaustive investigation to rule out organic disease. The American Gastroenterological Association’s current recommendations are to use patient symptoms supplemented with a narrow set of laboratory studies such as a complete blood cell count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and thyroid function tests in select populations. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) advises against routine serologic tests, stool studies, and abdominal imaging in patients with typical IBS symptoms and no alarm features (weight loss, anemia, family history of colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, or Celiac disease [CD]) because of a low likelihood of uncovering organic disease. In patients with IBS-D or IBS-M, serologic tests for CD should be ordered, and a colonoscopy should be performed for patients with alarm features to rule out other diseases. Patients older than 50 years who are diagnosed with IBS should also undergo a colonoscopy for screening for colon cancer, if not already performed.

There have been several symptom-based IBS criteria developed over the past few decades, but in general, they have not proven very practical for routine clinical use. The first of these criteria were put forth by Manning and colleagues in 1978 and included abdominal pain relieved by defecation, presence of frequent loose stools, passage of mucus, and abdominal distension as key symptoms of the disorder. In 1984, the Kruis criteria were developed that expanded on Manning’s by suggesting that patients with IBS should have a 2-year duration of symptoms in addition to a physical examination with negative results and normal results in serologic tests, including a CBC and ESR. The Rome criteria were developed in 1988 and have since undergone 3 iterations. Though frequently used in research studies, the Rome criteria are relatively cumbersome to use in daily practice, with a sensitivity and specificity that is not perfect for diagnosing IBS. Recognizing the limitations and shortcomings of the current IBS criteria, the ACG Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome has suggested a simpler and more concise definition: “Abdominal pain or discomfort that occurs in association with altered bowel habits over a period of at least 3 months.”

Given the patient’s young age, lack of “alarm signs,” and laboratory studies with negative results, you provide reassurance that this is less likely another condition and more likely a functional disorder such as IBS. During this office visit, you check her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels given her weight gain and fatigue and find them to be normal. For now you recommend that she need not have any further diagnostic testing. You instruct her to try a lactose-free diet and to keep a strict diet diary for the next 4 weeks to see if there are any obvious triggers for her symptoms. You plan to see her back in clinic in 1 month to see how she is doing.

Diagnosing IBS

In clinical practice, IBS symptoms are often heterogeneous and can masquerade as several other medical conditions. Because of this ambiguity, it is common for both general practitioners and gastroenterologists to order an array of expensive and invasive tests before the correct diagnosis is eventually made. National guidelines discourage this approach and recommend using clinical grounds to diagnose IBS without pursuing an exhaustive investigation to rule out organic disease. The American Gastroenterological Association’s current recommendations are to use patient symptoms supplemented with a narrow set of laboratory studies such as a complete blood cell count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and thyroid function tests in select populations. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) advises against routine serologic tests, stool studies, and abdominal imaging in patients with typical IBS symptoms and no alarm features (weight loss, anemia, family history of colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, or Celiac disease [CD]) because of a low likelihood of uncovering organic disease. In patients with IBS-D or IBS-M, serologic tests for CD should be ordered, and a colonoscopy should be performed for patients with alarm features to rule out other diseases. Patients older than 50 years who are diagnosed with IBS should also undergo a colonoscopy for screening for colon cancer, if not already performed.

There have been several symptom-based IBS criteria developed over the past few decades, but in general, they have not proven very practical for routine clinical use. The first of these criteria were put forth by Manning and colleagues in 1978 and included abdominal pain relieved by defecation, presence of frequent loose stools, passage of mucus, and abdominal distension as key symptoms of the disorder. In 1984, the Kruis criteria were developed that expanded on Manning’s by suggesting that patients with IBS should have a 2-year duration of symptoms in addition to a physical examination with negative results and normal results in serologic tests, including a CBC and ESR. The Rome criteria were developed in 1988 and have since undergone 3 iterations. Though frequently used in research studies, the Rome criteria are relatively cumbersome to use in daily practice, with a sensitivity and specificity that is not perfect for diagnosing IBS. Recognizing the limitations and shortcomings of the current IBS criteria, the ACG Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome has suggested a simpler and more concise definition: “Abdominal pain or discomfort that occurs in association with altered bowel habits over a period of at least 3 months.”

Given the patient’s young age, lack of “alarm signs,” and laboratory studies with negative results, you provide reassurance that this is less likely another condition and more likely a functional disorder such as IBS. During this office visit, you check her thyroid-stimulating hormone levels given her weight gain and fatigue and find them to be normal. For now you recommend that she need not have any further diagnostic testing. You instruct her to try a lactose-free diet and to keep a strict diet diary for the next 4 weeks to see if there are any obvious triggers for her symptoms. You plan to see her back in clinic in 1 month to see how she is doing.

Role of diet in IBS

Many patients with IBS think that diet plays an important role in their disorder and that avoiding certain foods can improve symptoms. Although the importance of diet in IBS remains debated, studies have shown that approximately two-thirds of patients with IBS report worsening of symptoms after a meal. A frequently heard clinical narrative is the sudden overwhelming urge to defecate within several minutes of eating. Although many patients assume this implies a food allergy, there are several other mechanisms that may account for these symptoms, including abnormal gas handling, abnormal colonic fermentation, psychosocial factors, intolerances to certain foods, and exaggeration of normal physiologic processes.

Adverse reactions to specific foods are reported in up to 45% of the general population and in up to 70% of individuals with IBS. These foods are often referred to as trigger foods, the most common of which are milk, wheat-containing products, fructose, caffeine, and certain types of meats. True immunoglobulin (Ig) E-mediated food allergies (eg, peanut or shellfish allergies) are rare and occur in only 1% to 4% of adults. There is no strong evidence to suggest that allergic food reactions play a significant role in IBS. In a study by Zar and colleagues, the presence of IgG4 antibodies to wheat was reported in 60% of patients with IBS compared with 27% of healthy controls. Another study demonstrated that patients with IBS had a substantial improvement in symptoms on elimination of specific foods to which they had IgG antibodies and had a marked worsening of symptoms on reintroduction of those foods. These results have not been widely replicated and controlled trials of elimination diets have been much more disappointing. In addition, detection of IgG antibodies to food is no longer considered a reliable diagnostic test for food allergy. Slow-onset immune responses to food (occurring over days to weeks) resulting from mucosa-based mast cells, T lymphocytes, and eosinophils may have a role in IBS symptoms, although the evidence is scant and still controversial. Examples of this type of immune response include CD (see later discussion), eosinophilic gastroenteropathies, and food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome. Evidence to suggest a role for this type of allergic reaction in IBS comes from the discovery of increased mast cell and eosinophil counts in close proximity to the enteric nerves within the mucosa of patients with IBS. Further evidence is needed to support this theory.

Poorly absorbed carbohydrates have been studied for their role in the development of IBS symptoms. Lactose is a disaccharide that is poorly digested and absorbed in most adults around the world. The true prevalence of lactose intolerance is unknown due in part to the varying incidence within different racial and ethnic populations and to the different definitions used for intolerance and malabsorption. Native American, Asian, and black populations have the highest reported rates of lactose intolerance (80%–90%), whereas the lowest rates are reported among Caucasians living in northern Europe, Australia, and North America (5%–10%). Individuals with lactose intolerance report abdominal distension, bloating, excess gas production, and diarrhea following the ingestion of milk and ice cream. Several studies have investigated lactose intolerance in IBS, and the available data are conflicting. Although some studies have shown no difference in the prevalence of lactose intolerance in IBS than that in the general population, others have demonstrated that anywhere from 40% to 80% of patients with IBS report significant symptom improvement on a lactose-restricted diet. It remains unclear whether the latter finding is because of true lactase deficiency or intolerance to another component in the restricted diet. Nonetheless, these 2 conditions share a very similar set of symptoms and can exist simultaneously in the same patient. Patients should be encouraged to keep a food diary to assess the relationship between symptoms and dairy intake, and if a consistent association is identified, consumption of milk, ice cream, and soft cheeses should be avoided or at least minimized.

Fructose is another poorly absorbed carbohydrate that has been implicated in the development of IBS symptoms. It is found in the diet as free fructose (fruits and honey), long polymers called fructans (wheat-containing products and onions), and the disaccharide, sucrose (table sugar). The consumption of fructose over the past 2 decades has increased dramatically as a result of the ubiquitous introduction of high-fructose corn syrup into food. Even in an average American diet, the amount of fructose ingested on a daily basis is sufficient to cause GI symptoms in healthy individuals. In a retrospective study, 38% of patients with IBS had significant improvement in pain, belching, bloating, and diarrhea when fructose was restricted. In another uncontrolled unblinded study, 46 of 48 patients who adhered to a strict fructose-restricted diet had a marked improvement in most of their IBS symptoms. When fructose and other nonabsorbed carbohydrates such as galactans are poorly absorbed in the small bowel, they are fermented by luminal bacteria into hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and short-chain fatty acids. These byproducts increase the osmotic load and levels of gas within the gut and act as a laxative leading to symptoms of bloating and diarrhea. There are several other dietary components, such as high fat and caffeine, and nonabsorbed carbohydrates and sugar alcohols, that are likely responsible for symptoms experienced by patients with IBS, but randomized controlled trials are currently lacking.

Fiber is one of the best studied yet most misunderstood dietary components in IBS. It has long been held that inadequate amounts of dietary fiber are responsible for the symptoms in IBS. Despite many systematic reviews and meta-analyses showing otherwise, this notion has been slow to change among practitioners, and patients with IBS are still counseled to increase the amount of insoluble fiber in their diets. The use of insoluble fiber as a bulking agent in IBS-D has been reviewed. Although the study populations were largely heterogeneous and the studies varied significantly in their methods, fiber was uniformly shown to have either no efficacy in IBS or only minimal effect in IBS-C (soluble fiber only).

Many patients both with and without IBS complain of adverse reactions to foods. Studies on diet in IBS are often difficult to interpret because of inadequate controls, poor methodology, heterogeneous populations, and a large placebo effect. Postprandial symptoms likely occur for several reasons including food intolerances, abnormal motility and gas handling, and psychosocial factors. True allergies to foods are possibly important for a small subset of patients but should probably be considered only in individuals with a history of atopy, allergic rhinitis, and/or asthma. In general, it is worth attempting a limited exclusion of food based on a diet dairy, understanding that the likelihood of complete sustained improvement is probably less than 20%. Focusing on foods that trigger symptoms within 1 to 3 days of ingestion will probably provide the highest yield, and patients should be instructed to pay particular attention to the ingestion of lactose, fructose, and high amounts of fat and caffeine.

After eliminating dairy products for 1 month, her symptoms have not improved, and a diet diary did not help identify any obvious food triggers. Over-the-counter antidiarrheal agents reduce her postprandial diarrhea, but her bloating and abdominal distension continue to be her biggest complaint. She has a great deal of flatulence, which has become socially embarrassing for her. These symptoms generally worsen throughout the day, and by dinner she is unable to fit into her pants comfortably. You order a measurement of vitamin B 12 and folic acid levels given her macrocytosis and a suspicion for SIBO. What is the yield of testing for bacterial overgrowth in IBS? Should we just treat empirically?

SIBO and IBS

Over the last several decades, there has been an increased interest in the role of SIBO in the pathogenesis of IBS. In addition to the substantial overlap in symptoms between these 2 disorders, there are several lines of evidence that provide support for this hypothesis. Bacterial overgrowth has long been known to disrupt epithelial absorption and secretion, but recent data also suggest that SIBO may be an important activator of mucosa-based immunity. Activation of proinflammatory cytokines by bacteria may alter epithelial cellular function, enhance nociceptive pain signaling, and alter intestinal motility—all purported pathophysiologic mechanisms in IBS. Bloating, abdominal distension, and excessive gas production are symptoms reported in up to 80% of patients with IBS. In fact, although the data are conflicting, there is evidence that patients with IBS produce and expel significantly more hydrogen gas than normal healthy controls. There is also evidence that these patients have increased amounts of small-intestinal gas on abdominal radiographs; however, there is not a strong correlation between these findings and the presence of symptomatic bloating. It has been subsequently suggested that the bloating and diarrhea in patients with IBS with excessive gas are caused by the overgrowth of the fermenting bacteria in the small bowel.

Under normal circumstances, the small intestine is a relatively sterile environment consisting of mostly gram-positive and, within the terminal ileum, gram-negative bacteria numbering between 10 5 and 10 8 colony-forming units (CFUs) per milliliter. In the colon, bacterial counts increase markedly (10 12 CFUs/mL), and the composition changes primarily to gram-negative bacteria, anaerobes, and enterococci. The bacterial count in the small bowel is maintained by normal peristalsis, gastric acid and mucus secretion, secretory IgA levels and an intact ileocecal valve. Predisposing conditions to the development of SIBO include altered gut anatomy (blind loops, surgical removal of ileocecal valve, small bowel diverticula), abnormal motility (scleroderma, diabetes), and decreased GI defense mechanisms (hypochlorhydria, immunodeficiency). In SIBO, abnormal migration of bacteria proximally into the small intestine results in premature fermentation of substrates, fat malabsorption, and consumption of carbohydrates and nutrients such as vitamin B 12 .

SIBO is defined by the presence of more than 10 5 CFUs/mL of colonic type bacteria in aspirates obtained from the proximal small bowel. Although many agree that direct aspiration and culture represents the gold standard for SIBO, there are several potential problems with this diagnostic approach, including the observation that SIBO is primarily a distal small bowel process that may not be adequately detected through proximal jejunal aspirates. In addition, there is no standardized approach in selecting an area of bowel to retrieve samples for analysis, anaerobes are difficult to collect and preserve without affecting total bacterial colony counts, and many if not most laboratories are not well versed in the correct method of counting and culturing bowel bacteria. In a recent systematic review of all the diagnostic tests for SIBO, no test was found to be appropriately validated, including the gold standard culture technique. Given the limitations of the gold standard, clinicians often rely on hydrogen breath tests to diagnose SIBO. These tests exploit the fact that bacterial fermentation of carbohydrates is the only source of hydrogen gas in the body. Hydrogen gas is readily absorbed from the gut lumen into the circulation and can be measured in breath samples in ppm. The lactulose hydrogen breath test (LHBT) is conducted by administering an oral 10-g dose of lactulose (a nonabsorbed sugar) and measuring breath samples for the presence of hydrogen gas every 15 minutes. In SIBO, an early detectable increase in hydrogen gas production corresponds to lactulose fermentation in the small bowel, followed shortly by a second increase that is attributable to normal colonic fermentation. This double peak is 1 of 3 criteria used to define an abnormal LHBT result. Other positive criteria include an increase in hydrogen of more than 20 ppm before 90 minutes and/or an absolute increase from baseline of 20 ppm by 180 minutes. Other carbohydrates, such as glucose or dextrose, can also be used for hydrogen breath testing.

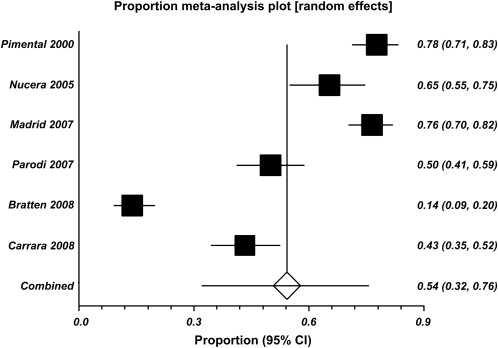

In their pivotal 2000 study, Pimentel and colleagues laid the groundwork for the SIBO-IBS hypothesis by showing that most patients with IBS (78%) have SIBO based on the results of LHBT. They also demonstrated that when these patients are treated with antibiotics and SIBO eradication is confirmed with LHBT, they have sustained symptomatic improvement. Since these data were published, several subsequent studies, including a large meta-analysis in 2009, have failed to demonstrate such a robust association. In their meta-analysis, Ford and colleagues evaluated 12 studies and 1912 subjects and found that the prevalence of SIBO in subjects meeting the diagnostic criteria for IBS was between 4% and 64% depending on the type of test and the criteria used to define a positive test. For the LHBT, 6 studies with 964 subjects were evaluated and the pooled prevalence of SIBO in patients meeting IBS criteria was 54% (95% confidence interval [CI], 32–76). However, there was substantial heterogeneity among all the studies, making interpretation somewhat difficult ( Fig. 1 ). In a 2007 Swedish study, 162 patients with IBS defined by Rome II criteria were tested for SIBO using jejunal aspirates and cultures. The prevalence of a positive test result was only 4% (95% CI, 2–6) when a value of more than 10 5 CFUs/mL was used. Some of the large differences in these findings have been argued to be the result of the poor test characteristics of the LHBT, possibly because of lactulose fermentation by gastric and oral flora or perhaps because of the effects of rapid transit times in some individuals (giving false-positive results). Whatever the reason for these discrepancies, the LHBT is likely not the best diagnostic test for SIBO and will probably be supplanted by more accurate tests in the future. More importantly, however, the pathologic consequences of SIBO in IBS have not yet been fully elucidated, and despite some positive data regarding the use of antibiotics for IBS, it is not entirely clear what do the antibiotics treat. Most recently, a double-blind placebo-controlled study by Pimentel and colleagues showed that administration of rifaximin at a dose of 550 mg 3 times daily for 2 weeks led to significant improvement in global IBS symptoms (40.7% vs 31.7%, P <.001) and bloating (40.2% vs 30.3%, P <.001) when compared with placebo. In the authors’ practice, a short empirical course of antibiotics (neomycin, rifaximin, or doxycycline) is administered, which serves both a diagnostic and therapeutic role, with the understanding that this approach is not something that is universally agreed on.

She returns to your office now having tried an empirical 2-week course of rifaximin for SIBO but is still without improvement. Her vitamin B 12 and folate levels were normal. Her best friend has CD and suggested that she try a gluten-free diet (GFD), which she plans to initiate within the next few days. Given her ongoing symptoms, you opt to expand your workup to include iron studies, stool studies for Giardia lamblia , and detection of tissue transglutaminase (tTG) and immunoglobulin (Ig) A. What is the prevalence of CD in patients with IBS, and are there individuals who should be routinely screened?