Women have started to enter gastroenterology (GI) in significant numbers over the past 5 years, although they are still underrepresented compared with the proportion of female graduating medical students. This underrepresentation is most likely caused by the culture of GI where female students and residents have felt undervalued and unwelcome. This type of discrimination is difficult to fight because it is behind the scenes. However, with increasing female role models in GI, this underrepresentation will likely change in the coming years.

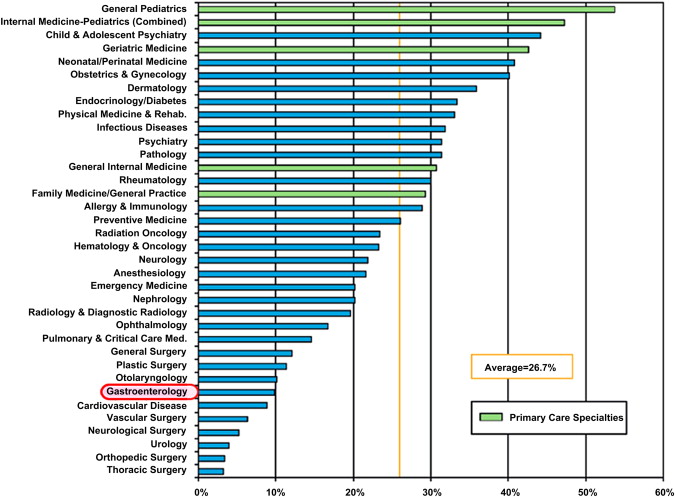

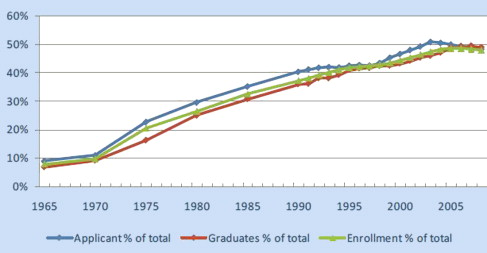

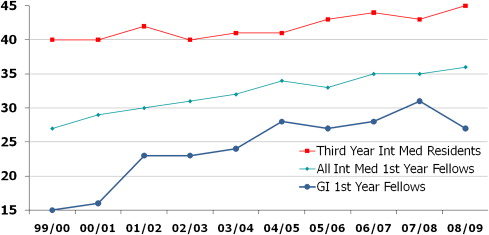

Gastroenterology (GI) has been one of the slowest fields in medicine to be embraced by women ( Fig. 1 ). It has been nearly 20 years since medical schools in the United States were populated almost 50% by women ( Fig. 2 ). Despite that fact, GI has only started attracting significant numbers of female physicians in the past 5 years. Of graduating medical students, a large percentage of women have chosen internal medicine as a career. More female than male internists choose to stay in primary care rather than subspecialize. Of the women who do decide to pursue a fellowship, few have historically chosen gastroenterology or cardiology. The percentage of female first-year gastroenterology fellows is still hovering around 25% to 30% ( Fig. 3 ). The reasons for this lack of interest in GI have not been well studied, although the assumption is that many women seek careers that are lifestyle friendly. Both GI and cardiology are perceived as subspecialties that have significant on-call responsibilities. This explanation is not completely satisfying because obstetrics and gynecology have long attracted many female medical students and yet clearly have an on-call requirement that is greater than GI. Another explanation is that the culture of GI has not been inviting to women, similar to what has occurred in surgery. A study performed many years ago found that 39% of female GI fellows perceived gender discrimination and 19% perceived sexual harassment during their training. Sexual stereotypes and biases against women can have a profound influence on a woman’s professional experience. Female medical students and residents are less likely to choose a profession if they do not receive the verbal encouragement and opportunities for advancement afforded to their male colleagues.

Hurtles unique to female gastroenterologists

Combining Child Rearing and Career

Perhaps the biggest hurtle to all female physicians is trying to combine career advancement and child rearing. Because of the length of medical training, many female physicians put off starting a family until they have finished their training, which takes them into their early 30s. At that age there is already a decreasing fertility rate giving a sense of urgency to starting a family. Although it is never easy to combine career and family for either gender, the burden of organizing childcare and family activities still tends to fall to the mother more than the father. This traditional female role is actually a full-time job in itself as exemplified by many full-time stay-at-home mothers. To combine this complex but rewarding job with a demanding medical career is daunting at best, and overwhelming at other times. In a survey of GI fellows, female fellows were more likely to choose programs according to parental leave policies and family reasons than the male fellows. Female fellows were also more likely than men to alter their family planning because of training program restrictions (20% vs 7%). In addition, they were more likely to remain childless or have fewer children at the end of training despite marital status, not unlike their male colleagues.

It has been estimated that most physicians work 55 to 60 hours per week; when you add 2 to 4 hours of reading journals, most full-time physicians are easily working more than 60 hours. Few other professions demand such a time commitment. This level of time commitment as a full-time career gastroenterologist is difficult to combine with raising a family. A lesser time commitment to one’s career for physicians is often equated with poor dedication to patients and less personal responsibility for continuing education.

One of the solutions to this conundrum is part-time work. There is no data on how often this is occurring in gastroenterology, either in private practices or in academic medical centers. Anecdotally, however, I know multiple women gastroenterologists who are now working part time. Many of them state that they still work what would be considered a full-time job in nonmedical fields, but what is considered part time in medicine. Historically, this was simply not an option. There is still some reluctance to offer part-time positions given the problem of covering patient issues on the physician’s days off. Part-time physicians also have the problem of paying for their overhead. Generally, the malpractice and support personnel needs are not easily scaled back for part-time physicians. There is no data looking at the competence of physicians who choose to work part time. However, given the large number of physicians who work part time clinically and spend the rest of the time in research or administration, it would appear that part-time clinical work does not adversely affect quality of care.

In a study that addressed the work satisfaction of part-time female physicians compared with their full-time counterparts, the part-time workers had lower career satisfaction if their marital and parental satisfaction was low; whereas, this correlation did not exist for the full-time physicians. The part-time female physicians were also more likely to consider leaving their employment entirely depending on interference of career with family. Both career satisfaction and intention to leave their employment were correlated with the quality of home life for reduced-hours physicians.

What are the solutions to this problem? First, it is important that female gastroenterologists support the reasonable work-hour demands of each other. For example, conferences should not be scheduled in early morning or evening hours. Family time and family responsibilities need to be respected. Second, it is important that female physicians be allowed to choose the number of hours that they want to work and to be paid appropriately, which is really quite simple in an relative value unit-based system. Lastly, there are 25 years of productive work after children enter school and 10 years after children are no longer at home. It would be unreasonable to lose 50% of our young physicians’ talent by not accommodating the early child-rearing years.

Challenges Unique to Endoscopy

Another challenge to female gastroenterologist is the male-oriented ergonomics of endoscopy. There is only one size of endoscope head. The left hand controls multiple functions: air, water, suction, picture capture, and the up/down and right/left dials. Nobody has studied whether this is more difficult with smaller hand sizes, although that is certainly conceivable. I have had many fellows tell me that other faculty have instructed them that they should never use the right hand to control the right/left dial; I tell them that is simply not true. There are numerous accomplished endoscopists who do that frequently. Indeed there are many ways to expertly perform endoscopy.

One area of gastroenterology that has had a particular dearth of women has been interventional endoscopy. Because there is clearly no evidence that men have greater dexterity or stamina than women, this dearth is most likely explained by the lack of encouragement of female GI fellows or frank discrimination. There have also been few role models available.

For female interventionalists, there is always the question of radiation exposure in the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography suite during pregnancy. Only recently the public and the press have come to realize that radiation exposure received by patients with medical imaging, such as computed tomography scanning, affects future cancer risk. There is even less data on the issue of radiation exposure of health care workers, particularly during pregnancy. Although the data suggests that the risk is either nonexistent or small, there are still several women in health care fields who avoid all radiation exposure during pregnancy. At many medical centers, the radiation safety departments recommend wearing a second radiation badge at abdominal level under the lead apron. Careful radiation control should of course be part of all of our work experience, although concerns about fetal exposure are greater. The National Council on Radiation Protection recommends limiting exposure to 100 mrem during the first trimester and 500 mrem during the entire pregnancy. Doses significantly lower than this should be obtained in the fluoroscopy room if the equipment is up to date and appropriate radiation control measures are taken. All interventional endoscopists should understand the basics of radiation safety in procedure rooms.

Is there a Glass Ceiling?

Although few women have chosen gastroenterology as a career, a disproportionally small percentage of them have been promoted to leadership positions in academic medical centers and in professional societies. Has this poor advancement been caused by discrimination or the old boys’ network, or is it caused by a lack of personal promotion and drive in many women, qualities that are simply not a part of the traditional female gender role? The author’s suspicion is that this lack of leadership positions is caused by both of the previously mentioned reasons, although one of the reasons that women do not promote themselves is that they have not been rewarded equally with men. When academic women have been surveyed, a high percentage of them feel that they have been discriminated against. Discrimination encountered by female physicians are often nonactionable micro-inequities, such as conscious and unconscious slights, including ignoring women at rounds or in discussions of patients and not crediting women’s ideas.

Discrimination has clearly happened in salary structures. Female medical school faculty neither advance as rapidly nor are compensated as well as professionally similar male colleagues. Deficits for female physicians are greater than those for nonphysician female faculty, and for both physicians and nonphysicians, women’s deficits are greater for faculty with more seniority. Female gastroenterologists are paid less even when number of hours worked are accounted for. A survey of gastroenterologists who were 3 and 5 years out of their training showed that academic female gastroenterologists made an average of 77% of their male colleagues salaries at 3 years and 76% at 5 years. A similar wage disparity occurs in nonacademic practices at 3 years post-training, although the differences improved at 5 years out of fellowship; whereas, it did not for academic women. However, it is also true that women do not tend to ask for much, whether it be salary raises or office and research space. Because the squeaky wheel tends to get greased, it is not surprising that women have not thrived; they do not tend to be self-promoters. Despite this difference in gender personalities, it is hard to deny that basic fairness should have equalized these wage gaps but failed to do so because of serious ongoing discrimination issues.

The flip side of the glass-ceiling problem is that women have also been highly sought after for positions of prominence. The low number of women in gastroenterology has historically helped promote some aspects of their careers. Many boards and committees have sought diversity in their ranks for more than 20 years and there have been few women to choose from. It is difficult to ascertain if this reverse discrimination has been sufficient to balance out the true discrimination that has occurred.

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment is characterized by unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature where submission is made either explicitly or implicitly a condition of an individual’s success. In a study of residents in internal medicine, 73% of women and 11% of men who responded reported that they had been sexually harassed at least once during their training. Many of the men who report harassment are gay men. About half of the reported incidents occurred during medical school and half during residency. Despite the frequency of sexual harassment, appropriate responses are rare because of either underreporting or noncorrective action.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree