Waiting List Management

Jay Lakkis

Matthew R. Weir

Gabriel M. Danovitch

Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Maryland, Baltimore, Maryland 21201; and Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California 90095

INTRODUCTION

The burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) continues to rise in a fashion that parallels that of diabetes mellitus (1). The United States Renal Data System (USRDS) 2003 Annual Data Report (ADR) identified 435,230 patients alive with ESRD by the end of 2001 (1).

The treatment of choice for the majority of these patients is kidney transplantation (2). When performed early after the onset of ESRD or preemptively in younger patients, that is, prior to initiation of renal replacement, patients benefit from the best renal allograft outcomes and the lowest mortality and morbidity rates (3, 4, 5, 6, 7). Thus, such a rising prevalence of CKD is inevitably reflected in a rise in the number of patients on the kidney transplant list, and only 27% of patients with ESRD will receive a kidney transplant.

The survival rates of renal allografts are limited in comparison to life expectancy. The typical cadaveric transplant today lasts only 13.4 years, whereas the living donor kidney lasts 21.0 years. Thus, many patients with failing renal allografts will be relisted, further expanding the number of patients on the transplant list in the face of organ shortage. Indeed, around 25% of patients registered with United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) are patients with prior renal allograft loss.

UNOS currently reports that there are 55,735 patients on the waiting list for a kidney transplant, and 2,408 for pancreas-kidney transplant. In 2002, there were 11,867 kidney donors of whom 52.5% (6,236) were live donors, and 47.5 % (5,631) were deceased donors; around 14,775 kidney transplants took place of which 57.8% (8,539) were from the deceased donors, and 42.2% (6,236) were from the live donors. In the first half of 2003, there were 5,934 kidney donors of whom 53% (3,144) were live donors, and 47% (2,790) were deceased donors; around 7,394 kidney transplants took place of which 57.5% (4,250) were from the deceased donors, and 42.5% (3,144) were from the live donors (8).

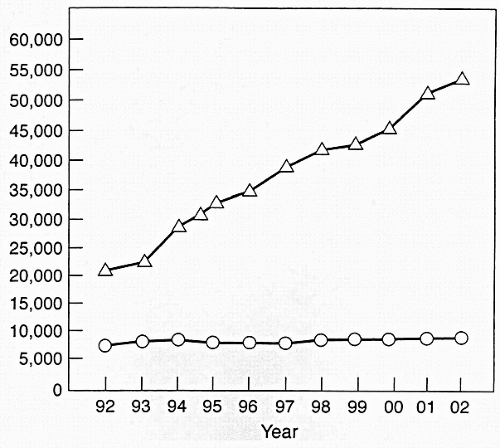

The number of kidney allografts procured from deceased donors has been fairly constant over the past few years but the number of organs donated by living subjects has been steadily increasing and exceeded the number of deceased donors for the first time in 2001 (8) (Fig. 4.1). However, this increase is far from meeting the shortage in organs needed; the UNOS kidney waiting list is currently increasing at a rate of 20% per year and is expected to include around 100,000 patients by the year 2010 (9). In brief, the gap between supply and demand is steadily widening, and this will be reflected by steadily increasing waiting times. Thus, strategies for optimal medical management of this burgeoning population is needed to be sure the patients are healthy to undergo transplantation.

FIG. 4.1. Relationship between number of deceased donor kidneys transplanted (circles) and number of patients waiting (triangles) since 1992. (From Ref. 8, with permission.) |

THE TIMING OF THE REFERRAL

Early and timely referral of the patient with CKD for kidney transplantation is essential and does alter the patient mortality and morbidity rates. However, there is a significant delay in providing renal replacement choices, as most eligible transplant recipients in the United States have not been placed on a waiting list within 6 months after beginning dialysis. This delay, along with other deficiencies in medical care for patients with advanced CKD, adversely affect quality of life and survival of patients (10). The UNOS points system for patients on the kidney transplant list adds points for waiting time only when the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is 20 mL/min or less (8).

THE EVALUATION PROCESS

With the quality of life and survival advantage with transplantation, most patients with CKD should be considered candidates with few exceptions. In fact, there are few absolute contraindications to kidney transplantation, namely, a cancer that is not in remission, an active systemic infection, or a disease state with a life expectancy of less than 2 years. Other relative contraindications to kidney transplantation include active substance abuse and medical noncompliance. But, in both cases, the patient may be counseled and such barriers may be alleviated over time. There have been recent trends to transplant special patient populations previously not thought to be candidates, such as elderly patients with comorbid conditions, highly sensitized patients with a high panel-reactive antibody (PRA) or a positive T-cell crossmatch, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients, and patients with mental retardation. Once a referral is made to a transplant center, the patient undergoes a series of coordinated multidisciplinary interviews and workups, which would, in the absence of any barriers, ultimately result in being placed on the list if a suitable living kidney donor cannot be identified.

The patient is assigned to a transplant team, and the latter provides educational material about the transplant process, its risks and benefits, and types of donor source in order for the patient to make informed and educated decisions. The team also identifies any potential contraindications to the transplant process prior to initiation of a costly workup.

The medical evaluation aims at preventing mortality, mainly from cardiovascular disease, in patients with kidney transplantation. A comprehensive history and physical examination should be obtained with focus on original kidney disease, potential contraindications for transplantation, comorbid conditions and their inferred intraoperative and postoperative risk, and use of tobacco, ethanol, or illicit substances. Also, a systematic cardiac evaluation should be performed in patients eligible for transplantation; being a very high-risk group for cardiovascular events, the majority of patients end up receiving a cardiac stress test or a coronary angiogram prior to surgery. Tests also include blood and tissue typing, a complete blood count, a basic metabolic profile, a chest x-ray, an abdominal ultrasound, a dental evaluation, and age-appropriate screening for malignancy. Additional tests may be required based on compelling indications.

Furthermore, the medical evaluation should incorporate an assessment of the nutritional status of the patient with

CKD; in a recent study, malnutrition was identified as an independent risk factor for mortality in CKD patients on hemodialysis and was the direct cause of death in 5% of the cases (11). Also, persistent hypoalbuminemia in patients after simultaneous kidney-pancreas transplantation is associated with an increased risk for morbidity and graft loss and a trend toward decreased survival. Efforts to improve nutrition may improve outcome (12).

CKD; in a recent study, malnutrition was identified as an independent risk factor for mortality in CKD patients on hemodialysis and was the direct cause of death in 5% of the cases (11). Also, persistent hypoalbuminemia in patients after simultaneous kidney-pancreas transplantation is associated with an increased risk for morbidity and graft loss and a trend toward decreased survival. Efforts to improve nutrition may improve outcome (12).

More details about the medical evaluation are provided elsewhere. However, many of the same considerations involved in the initial evaluation will recur as part of the ongoing evaluation of the patient’s health while on dialysis.

The role of the pretransplant psychiatric or psychological evaluation has been well established. In fact, such an assessment is associated with an improved quality of life posttransplant (13). Patients should be counseled in an attempt to minimize the psychological impact of a failed kidney transplant or episodes of rejection. Fukunishi et al (14) evaluated 36 patients with ESRD and estimated the prevalence rate of psychiatric disorders at 11.1% pretransplantation and at 36.1% within 2 months posttransplantation; no patients without schizophrenia had any psychiatric disorder from 2 to 6 months posttransplantation. In another study that evaluated 16 patients with ESRD, the incidence of anxiety was 68.8% pretransplant and 81.3% posttransplant (15). The range of psychiatric disturbances is variable and may include anxiety, depression, alexithymia, dysthymia, behavioral problems, a sense of guilt in recipient toward the living donor, posttraumatic stress, and psychosis related to allograft rejection or loss (15, 16, 17, 18, 19). Again, the initial psychiatric evaluation is important. But additional follow-up is needed on dialysis, not only with regard to general mental health, but also substance abuse and issues surrounding non-compliance.

In addition to psychiatric sequelae, efforts should also be made to anticipate issues with patient recovery and rehabilitation such as functional recovery, stress and coping, quality of life, and adherence with medications. Thus, the previous workups must be complemented with comprehensive social, economic, and financial evaluations in an attempt to identify potential pre- or posttransplant problems. Review of the patient’s insurance coverage is of utmost importance, since the transplant process is costly and may deplete a patient’s resources resulting in adverse outcomes.

THE ALLOCATION PROCESS: IMPLICATIONS FOR WAITING LIST MANAGEMENT

After evaluation by the transplant physician, a patient is added to the national waiting list by the transplant center. Lists are specific to both geographic area and organ type. Each time a donor organ becomes available, the UNOS computer generates a list of potential recipients based on factors that include genetic similarity, blood type, organ size, medical urgency, and time on the waiting list. Through this process, a “new” list is generated each time an organ becomes available that best “matches” a patient to a donated organ.

Kidney Allocation Considerations

Current allocation strategies facilitate the national sharing of highly matched kidneys but also place importance on waiting time. The inclusion of waiting time in the overall allocation algorithm has always been viewed as intuitively equitable. However, future considerations about allocation in part will deal with issues of both equity and utility (20).

The issue of waiting time is an important concern. Currently, the waiting list is accruing more and more biologically disadvantaged patients who have uncommon blood types or broad sensitization against human leucocyte antigens. The net result is an accruing list of waiting list patients who have a very low likelihood for ever receiving a kidney transplant. More important is the concern that waiting list time disadvantages these patients in two respects: (a) places them at a greater risk for acute rejection and graft dysfunction and (b) reduced long-term survival. Thus, with increased time and accumulated waiting points in the allocation algorithm, longer-wait patients will rise in the list despite the fact that they have a worse long-term success rate. Ideally, the best time to get a transplant in order to optimize long-term function is predialysis. Increasing time spent on dialysis of up to 4 years confers an approximately 70% increased mortality risk and graft loss compared with preemptive or predialysis transplantation. In addition, as will be discussed later, while waiting on dialysis, patients develop substantial comorbidity, which is primarily related to the cardiovascular system. Despite these concerns, transplantation continues to provide an improvement in mortality risk compared with dialysis even for patients with prolonged waits.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree