10 Vomiting blood, black stools, blood per rectum, occult bleeding

Case

A 67-year-old male presents to the emergency department with a history of a massive haematemesis (fresh blood) over 12 hours. He was unwell and also complained of syncopal episodes. He had no previous episodes. There was a past history of hepatitis C infection. Alcohol consumption was 120 g/day, which he ceased 2 years back.

Introduction

Five different clinical situations are commonly encountered:

The approach to management of these clinical situations forms the basis of this chapter.

Vomiting Blood

The main causes of haematemesis are listed in Box 10.1. So how do these patients present? They may feel nauseous and even continue to vomit during the initial assessment or have symptoms related to blood loss including sweating, dizziness and confusion.

Management

Hypotension and shock

Assessment of hypovolaemia involves simple bedside clinical observations. The patient may be clammy and sweaty with cold peripheries and a fast thready pulse. There may be associated confusion. The blood pressure will be low, often under 90 mmHg systolic. If any of these signs are seen, resuscitation should commence immediately. At least two large-bore intravenous cannulae should be inserted into large peripheral veins. A central venous line should be placed in high-risk cases (see below). Rapid infusion of isotonic saline followed by a plasma expander such as Haemaccel® should be commenced and blood samples should be drawn urgently for full blood count, coagulation screen, blood group and cross-matching of four to six units of packed cells, and urea, electrolytes and liver function tests.

Patients with a gastrointestinal bleed have lost ‘whole blood’ and there is, therefore, logic in transfusing them with whole blood (Box 10.2). In practice, however, donated blood is separated into packed cells and other products, such as platelets and plasma, which may be used in different clinical situations. Thus, in current clinical practice, patients with a significant bleed are given packed cells alternating with a plasma expander such as Haemaccel if they are hypovolaemic and packed cells alone if they are normovolaemic but anaemic. The aim of transfusion is to restore circulating blood volume so that the blood pressure is normal and to correct anaemia so that the oxygen carrying capacity of the blood is satisfactory. This generally means maintaining a haemoglobin level of approximately 100 g/L. One unit of packed cells will increase the haemoglobin level by 10 g/L (haematocrit by 3%).

Source of the bleed

Endoscopy

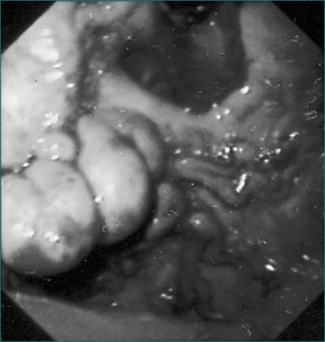

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is the single most useful test. If performed within 24 hours of presentation, the cause of bleeding will be found in 90–95% of patients (Figs 10.1 to 10.3). Furthermore, it may permit the endoscopist to perform therapeutic interventions that in turn may arrest the bleeding or minimise the chance of further bleeding. It requires considerable expertise, especially in the situation of an actively bleeding lesion, and is not without some risk.

So who should be endoscoped and when should it be done? This decision is more easily made if consideration is given to why the endoscopy is being done. First, the aim is to make an accurate diagnosis. Secondly, a prognosis for further bleeding may be given, based on the endoscopic findings. Finally, a bleeding lesion or one at high risk of re-bleeding may be able to be treated. However, if the patient is not in a high-risk category, it may not be necessary to do an emergency procedure. In general terms, endoscopy should always be done within 24 hours but, for patients considered being at ‘high risk’, particularly if there is a possibility of oesophageal varices, emergency endoscopy should be arranged once the patient has been adequately resuscitated.

Risk factors for greater morbidity and mortality from haematemesis are now well known and are listed in Box 10.3.

Box 10.3 High risk features in patients with haematemesis

Common causes of haematemesis

Oesophageal varices

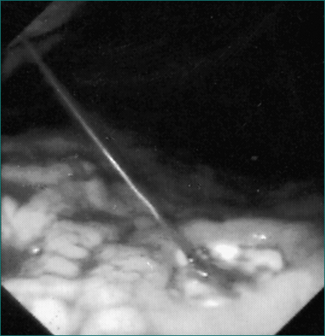

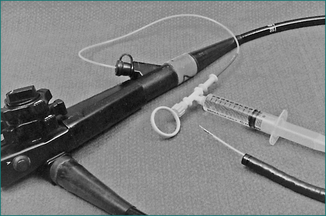

If bleeding oesophageal varices are found during endoscopy, rubber band ligation is the current treatment of choice. Bleeding can be controlled in 80–90% of cases with a relatively low risk of complications. If passage of the rubber band ligating device mounted on the tip of the endoscope is not feasible or if equipment and expertise for rubber band ligation are not available, injection sclerotherapy may be performed (Fig 10.4). This involves direct injection of a sclerosant such as ethanolamine oleate or sodium tetradecyl sulfate into the varices. Injection sclerotherapy has a very high success rate in controlling the bleeding, although with a greater risk of complications including sepsis, oesophageal stricture and mediastinitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree