The main problems associated with venous catheters are infection, poor flow, thrombosis, and central venous stenosis.

I.

INFECTION. Despite the best practices detailed in

Chapter 7 (

Table 7.3), infections do occur with venous catheters, and at a rate substantially higher than with arteriovenous (AV) fistulas. Infection is the leading cause of catheter loss and increases morbidity and mortality. Most often, infection results from contamination of the catheter connectors or from lumen contamination during dialysis or from infused solutions. Infection also may arise from the migration of the patient’s own skin flora through the puncture site and onto the outer catheter surface. Catheters can sometimes become colonized from more remote sites during bacteremia.

A. Exit-site infection can be diagnosed when there is erythema, discharge, crusting, and tenderness at the skin exit site, but no tunnel tenderness or purulence. Treatment with topical antibiotic cream and oral antibiotics may be sufficient. These infections can be prevented by meticulous exit-site care. The patient should be investigated for nasal carriage of Staphylococcus and if present, treated with intranasal mupirocin cream (half tube twice a day to each nostril for 5 days) to prevent future infections. With exit-site infection, the catheter must be removed if systemic signs of infection develop (leukocytosis or temperature >38°C), if pus can be expressed from the track of the catheter, or if the infection persists or recurs after an initial course of antibiotics. If blood cultures are positive, then the catheter should be removed.

B. Tunnel infection is infection along the subcutaneous tunnel extending proximal to the cuff toward the insertion site and venotomy. Typically, there is marked tenderness, swelling, and erythema along the catheter tract in association with purulent drainage from the exit site. This can result in systemic bacteremia. In the presence of drainage or signs of systemic infection, the catheter should be removed immediately and antibiotic therapy prescribed.

C.

Catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI). Patients present with signs and symptoms of systemic infection, which may

range from minimal to severe. Milder cases present with fever or chills, whereas more severe cases exhibit hemodynamic instability. Patients may develop septic symptoms after initiation of dialysis, suggesting systemic release of bacteria and/or endotoxin from the catheter. There can be signs of metastatic infection, including endocarditis, osteomyelitis, epidural abscess, and septic arthritis. Gram-positive organisms are the causative organisms in the majority of cases, but gram-negative infections occur in a very sizeable minority. For details on how to treat CRBSI in dialysis patients, caregivers can refer to valuable information available on the dialysis section of the U.S. Centers of Disease Control (CDC) website (http://www.cdc.gov/dialysis), the NKF KDOQI 2006 vascular access guidelines (NKF, 2006), the European Renal Best Practices (ERBP) access guidelines (

Tordoir, 2007), the Infectious Disease Society of North America (IDSA) guidelines update for management of CRBSI (

Mermel, 2009), and the ERBP commentary on the IDSA guidelines (

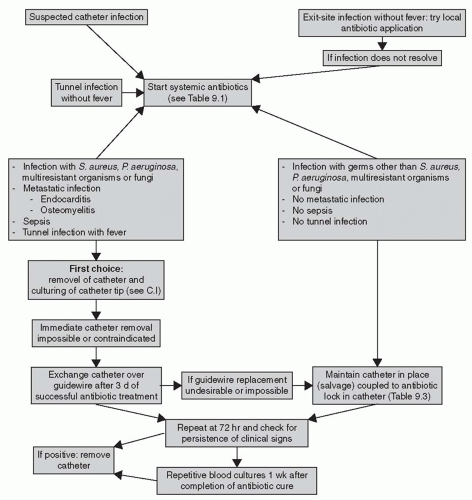

Vanholder, 2010). Treatment algorithms and tips from the IDSA are reproduced in

Figure 9.1 and

Tables 9.1 and

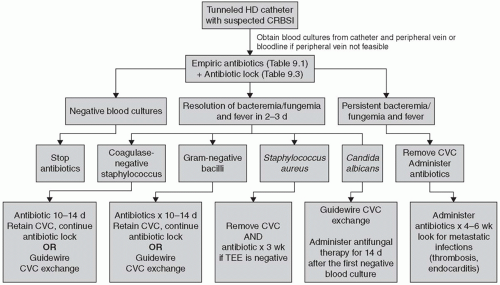

9.2, and key recommendations from the ERBP are shown in

Figure 9.2.

The principles of CRBSI management in dialysis patients are different from the infectious disease guidelines for treatment of infection in short-term central venous catheters. In hemodialysis, the venous catheter is a lifeline that sometimes can be replaced only with great difficulty. Thus, the guidelines include a variety of catheter salvage maneuvers, which involve use of antibiotic-containing catheter locks or replacing the infected catheter with a new catheter in the same location over a guidewire. However, these catheter salvage techniques should be used only in limited, defined circumstances. If a patient’s condition worsens after a relatively short trial of catheter salvage, the catheter must be removed to minimize the risk of spreading the infection to body organs.

1.

Blood and catheter tip cultures. In working up a suspected CRBSI, cultures can be obtained from the catheter hub, from a peripheral vein, or from the blood lines during dialysis treatment. The IDSA recommendations are to take blood cultures from a catheter hub and from a peripheral vein and, when a catheter has been removed because of suspicion of infection, to also culture the distal 5 cm of its tip. One is looking for both blood cultures or for both the blood culture and a catheter tip culture to be positive with the same organism to confirm a diagnosis of CRBSI. When taking cultures from the skin or from a catheter hub, the IDSA recommends cleaning and sterilizing the area with alcoholic chlorhexidine rather than povidone-iodine, and allowing the antiseptic to dry before sampling; this avoids contamination of the cultured material with liquid antiseptic. The IDSA guidelines recognize that obtaining blood from the dialysis bloodline is an acceptable

substitute for peripheral blood cultures in many hemodialysis patients.

The ERBP ad hoc advisory recommendations are similar to what the IDSA recommends. They too, recognize the difficulties in obtaining cultures from peripheral veins in hemodialysis patients, and believe that a practical alternative is to simply draw blood cultures from the dialysis circuit. Blood from the circuit during dialysis probably represents peripheral blood rather than localized catheter blood, and so a positive blood culture drawn from the bloodline may reflect a source of bacteremia other than at the catheter. The ERBP group suggests that the best way to deal with this possibility is by evaluating clinical history, examination, imaging, and targeted laboratory testing, including urine culture if possible.

2. Indications for immediate catheter removal. If there is evidence of septic thrombosis, endocarditis, or osteomyelitis, or of severe sepsis with hypotension, then the dialysis catheter needs to be removed immediately. The same recommendation generally holds for tunnel infection with fever. Dialysis should be continued with a temporary catheter inserted at a different location.

3.

Choice of antibiotic. Gram-positive organisms, primarily

Staphylococcus spp., are the most common, but gram-negative organisms may be isolated in up to 40% of cases. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be started immediately after drawing cultures. Dialysis units should keep a database of all CRBSI, including causative organisms, their susceptibility, and response to therapy, as this information is extremely valuable in guiding antibiotic therapy for new cases. If methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus is known to be common in the local hemodialysis population, the initial therapy should include vancomycin, rather than a first-generation cephalosporin. Adequate empiric gram-negative coverage can be provided with either an aminoglycoside or a third-generation cephalosporin. However, aminoglycosides may cause ototoxicity in up to

20% of hemodialysis patients. If treatment was begun for methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus and the culture shows a methicillin-sensitive organism, the treatment should be changed to cefazolin or a similar antibiotic.