Fig. 31.1

Distribution of vessel involvement by large-vessel vasculitis, medium-vessel vasculitis and small-vessel vasculitis. Note that there is substantial overlap with respect to arterial involvement, and an important concept is that all three major categories of vasculitis can affect any size artery. Large-vessel vasculitis affects large arteries more often than other vasculitides. Medium-vessel vasculitis predominantly affects medium arteries. Small-vessel vasculitis predominantly affects small vessels, but medium arteries and veins may be affected, although immune-complex small-vessel vasculitis rarely affects arteries. The diagram depicts (from left to right) aorta, large artery, medium artery, small artery/arteriole, capillary, venule and vein. Anti-GBM—anti–glomerular basement membrane; ANCA—anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. ANCA Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. (Reprinted with permission John Wiley and Sons/Arthritis & Rheumatism, from Ref. [2], 2013 American College of Rheumatology.)

Table 31.1

Classification of the vasculitides. (Reprinted with permission John Wiley and Sons/Arthritis & Rheumatism, from Ref. [2], 2013 American College of Rheumatology.)

Large-vessel vasculitis (LVV) |

Takayasu’s arteritis |

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) |

Medium-vessel vasculitis (MVV) |

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) |

Kawasaki disease (KD) |

Small-vessel vasculitis (SVV) |

(i) Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) |

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss) |

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis) |

Microscopic polyangiitis |

(ii) Immune-complex SVV |

IgA vasculitis (Henloch–Schӧnlein; IgAV) |

Cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis |

Hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis |

Anti-glomerular basement membrane disease |

Variable-vessel vasculitis (VVV) |

Behcet’s disease |

Cogan’s syndrome |

Single-organ vasculitis (SOV) |

Vasculitis associated with systemic disease |

Lupus |

Rheumatoid |

Sarcoid |

Secondary vasculitis |

Hepatitis B/Hepatitis C |

Drugs |

Others |

Table 31.2

Vasculitides associated with gastrointestinal manifestations in childhood

Henoch-Schӧnlein purpura |

Kawasaki disease |

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) |

ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) |

Behcet’s disease |

Systemic disease (Lupus and Rheumatoid) |

Henoch–Schönlein Purpura

HSP is an immune-complex small-vessel vasculitis. It is the most common vasculitis seen in childhood with an estimated annual incidence of 20/100,000 children in the UK . The disease is characterized by a leukocytoclastic vasculitis with deposition of immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1) immune complexes in vascular tissue, principally capillaries and post-capillary venules. The disease is predominantly seen in children aged 3–10 years with the majority being < 5 years. It is more frequent in the autumn/winter months and will commonly follow an infection. Proposed infective triggers include group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus, Parvovirus B19, Staphylococcus aureus and Coxsackie virus to name a few. It has been suggested that the pathogenesis involves the recognition of galactose-deficient IgA1 by anti-glycan antibodies and the deposition of these immune complexes in small vessels .

A recent large series suggests that 100 % of patients have skin involvement with 60–70 % having “palpable purpura” of the lower limbs and buttocks, 66 % have arthritis which is usually symmetrical affecting the knees, ankles and feet, and 54 % have GI involvement usually with lower GI bleeding or abdominal pain but also intussusception , ileal perforation and pancreatitis [3]. Renal manifestations are seen in 30 % and include nephritic or nephrotic syndromes which can lead to chronic renal failure in a minority of cases. Diagnostic criteria include the presence of purpura or petechiae with lower-limb predominance with one of the following: diffuse abdominal pain , acute arthritis or arthralgia, haematuria or proteinuria and any biopsy showing predominant IgA deposition [4].

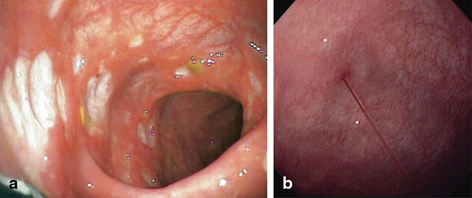

Described GI complications of HSP include intussusception, bowel ischaemia and infarction, intestinal perforation, late stricturing, acute appendicitis , GI haemorrhage (occult and massive), pancreatitis and gallbladder hydrops. One large series of patients reported abdominal pain in 58 % of children and positive stool occult blood (SOB) in 18 % [5] . Frank lower-GI bleeding was present in 3 %. Plain abdominal radiology frequently showed dilated thickened bowel loops when the SOB was strongly positive which was also visualised on ultrasound examination. Intussusception , perhaps the most serious GI complication of HSP, was rare (0.5 %) although in other series prevalence of up to 5 % are described. The appearance of the thickened bowel wall on ultrasound might act as a prognostic marker for duration of hospitalization for HSP [6]. Endoscopic findings vary and can include the presence of circumscribed vascular lesions (rather similar to the palpable purpura seen on the skin) and segmental ischaemic change (Fig. 31.2) [7] .

Fig. 31.2

Cutaneous purpura and small bowel hyperaemia with ulceration in a young adult with HSP. (Reprinted from Ref. [7], with permission from Elsevier.)

It is usual for children to make a complete recovery from HSP with only supportive treatment with the exception of HSP-associated nephritis which is the cause of end-stage renal failure in up to 3 % of children in the UK. Some series report a significant reduction in duration and intensity of abdominal pain in children treated with prednisolone early in the course of the disease, but the use of steroids does not seem to protect against the development of nephritis.

Kawasaki Disease

KD is the second commonest childhood vasculitis which affects about 8/100,000 children younger than 5 years of age annually in the UK with twice as many cases occurring in the USA and approximately 20 times the incidence in Japan. The disease affects predominantly medium- and small-sized arteries and is normally self-limiting. However, coronary artery aneurysms are present in 25 % of untreated patients and can lead to myocardial infarction or late coronary artery stenosis. In addition to involvement of the coronary arteries, systemic arterial injury can occur.

The seasonality and clustering of KD support an infectious trigger, although to date no single organism has been identified. The much higher prevalence of disease in Japanese and Korean children supports the notion that genetic predisposition is also an important factor and genome-wide association studies have identified a number of genes associated with disease susceptibility and disease phenotype.

Diagnosis of KD is clinical comprising the presence of unremitting fever for 5 days or more plus 4/5 of the following features: conjunctivitis; lymphadenopathy; polymorphous rash; changes in lips, tongue or oral mucosa and involvement of extremities including periungual desquamation (see Table 31.3). Patients with lesser numbers of these diagnostic features may be diagnosed with KD if they are found to have coronary artery aneurysms on echocardiography. It is important to note that not all of these diagnostic features may be present at once.

Table 31.3

Diagnostic criteria for Kawasaki Disease

Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

Fever | Duration of 5 days or more plus 4/5 of the following |

1. Conjunctivitis | Bilateral non-purulent with limbic sparing |

2. Lymphadenopathy | Cervical, often > 1.5 cm |

3. Rash | Polymorphous with no vesicles or crusts |

4. Changes in lips/mucus membranes | Red cracked lips, “strawberry” tongue, erythema of oropharynx |

5. Changes in extremities | Initially: erythema and oedema of palms and soles |

Later: periungual desquamation |

Although not diagnostic of KD, arthritis, aseptic meningitis, pneumonitis, uveitis, gastroenteritis and dysuria are also frequently seen. Uncommon features of the disease include gallbladder hydrops, GI ischaemia, mononeuritis, nephritis, seizures and ataxia.

Overall, abdominal symptoms, particularly diarrhea which can be bloody or non-bloody, are a frequent early feature of KD. Abdominal pain is less frequent [8]. Vasculitic appendicitis , haemorrhagic duodenitis and paralytic ileus are also described [9]. Bowel wall oedema may be evident as segmental thickening of the bowel wall as may gallbladder hydrops [10].

Inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, ESR and C-reactive protein, CRP) are inevitably elevated as is the peripheral blood white blood cell count. Thrombocytosis, which can be very marked, usually occurs in the second week of the disease.

Early treatment of KD with aspirin and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) reduces the occurrence of coronary artery aneurysms. A single infusion of 2 g/kg IVIG and an anti-inflammatory dose of aspirin (30–50 mg/kg/day) will reduce the likelihood of developing coronary artery aneurysms in the majority of patients, although approximately 20 % of children are IVIG resistant. The dose of aspirin should be reduced to an anti-platelet dose during the thrombocytosis phase of the illness. Patients who continue to have fevers and an ongoing systemic inflammatory response 48 h post IVIG are likely to be IVIG nonresponders and can be treated with intravenous methyl prednisolone for 5 days followed by 2 weeks of oral prednisolone or perhaps anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) antibodies. Certain other high-risk individuals should also receive steroids [11].

Systemic Polyarteritis Nodosa

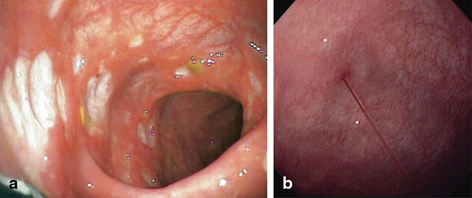

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a necrotizing arteritis of medium and/or small arteries which has been subclassified into systemic PAN and cutaneous polyarteritis. Whilst systemic PAN is generally severe and cutaneous polyarteritis relatively benign, the cutaneous form can go on to develop features of multiorgan involvement. The presenting features of PAN can be very nonspecific and are known to affect a number of systems notably the skin, musculoskeletal system, kidneys and GI tract. A recent pediatric series documents the most common presenting features of PAN as fever (87 %), myalgia (83 %), arthralgia/arthritis (75 %), weight loss of > 5 % of body weight (64 %), fatigue (62 %), livedo reticularis (49 %) and abdominal pain (41 %). In this series, 59 % had GI symptoms comprising abdominal pain (49 %), blood in the stools (10 %) and bowel ischaemia/perforation (8 %) [12]. The diagnosis may be delayed as the symptoms are so nonspecific. GI bleeding can be massive, especially when it arises from a Dieulafoy lesion, a submucosal vascular abnormality with a prominent tortuous artery with/without aneurysm formation [13, 14]. Ulcers, which are circumscribed and well demarcated, may also be evident (Fig. 31.3a, b). Following remission induction in PAN, the onset of GI symptoms is a major clinical predictor of clinical relapse. Other symptoms seen in PAN less frequently include cardiac, respiratory and neurological manifestations.

Fig. 31.3

a Punched-out ulcers with well-demarcated edges in the colon in PAN. Ulcers are typically shallow and irregular often with surrounding erythema. (Reprinted from Ref. [15], with permission from Elsevier). b Bleeding Dieulafoy lesion in the stomach in a case of PAN. (Reprinted from Ref. [14], with permission from Elsevier.)

GI symptoms are generally attributable to ischaemia which can lead to infarction, perforation or stricture [16, 17]. The systemic vasculitides can also be associated with an ischaemic colitis or a nonspecific colitis that can mimic inflammatory bowel disease [18].

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree