14 Vaginal Repair of Urethrovaginal and Vesicovaginal Fistulae

To view the videos discussed in this chapter, please go to expertconsult.com. To access your account, look for your activation instructions on the inside front cover of this book.

1. Perform adequate exposure and mobilization of the fistula track.

2. Reapproximate healthy tissue in several layers to ensure a watertight closure.

3. Ensure tension-free suture lines.

4. Interpose a healthy, well-vascularized tissue flap when necessary.

5. Provide adequate diversion of urine during the postoperative period to allow complete healing.

The vaginal approach is an ideal approach that allows exposure of the fistula and preparation of the tissue layers and a well-vascularized flap for interposition. This chapter reviews and demonstrates the technical steps required to successfully correct urethrovaginal and vesicovaginal fistulae via a vaginal approach.

Preoperative Evaluation

Physical Examination

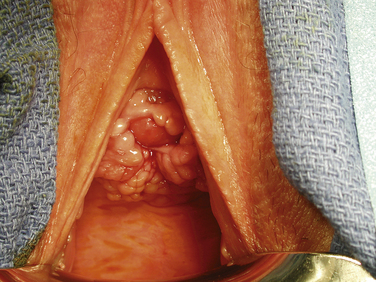

Vaginal speculum examination should be performed to visualize the fistula. For a VVF, when a full speculum is placed, the first observation is usually that of a urine-filled vaginal vault. Depending on the patient’s anatomy, the fistula may best be seen by using a full speculum to retract both the anterior and posterior vaginal wall. This is particularly true when the fistula is located at the vaginal cuff, the most common site for a VVF occurring as a result of hysterectomy. When the fistula is more distal, it is helpful to use the bottom blade of a Graves speculum to facilitate careful visualization of the anterior vaginal wall. The half-speculum is placed along the posterior vaginal wall with mild traction downward to expose the aforementioned compartments. The fistula is often surrounded by granulation tissue. Palpation of the vaginal cuff and anterior vaginal wall may reveal the opening as well as suture material at the vaginal cuff near a presumed fistula. In addition, a urethral catheter can be placed and the bladder filled with a solution of either indigo carmine or methylene blue diluted in sterile saline. This maneuver can help both to confirm and to identify fistula location. If extravasation of blue-tinged fluid is not seen during speculum examination, a tampon or gauze packing can be placed vaginally and the patient can ambulate or sit upright for 10 to 15 minutes. Subsequent inspection of the gauze revealing blue staining is indicative of a lower urinary tract fistula. If there is no blue staining of the vaginal gauze but the gauze appears saturated with yellow urine, a ureterovaginal fistula must be suspected. This possibility can be further investigated with computed tomographic (CT) urography (see later section on imaging).

Imaging

Imaging is not always mandatory to diagnose and treat a VVF, though it is important to rule out a ureterovaginal fistula in cases where such a finding is possible (e.g., after pelvic surgery such as hysterectomy). Standard cystography, CT cystography, or pelvic magnetic resonance imaging can allow identification and further characterization of a VVF. In cases in which the fistula is not obvious on physical examination or endoscopy, we prefer standard cystography as the simplest and most reliable initial method of diagnosis. A Foley catheter is placed via urethra and the bladder is filled under gravity drainage with a contrast solution. Standard radiographic or fluoroscopic images are obtained in both the anteroposterior and lateral orientations. A VVF is typically most readily identifiable in the lateral orientation as a wisp of contrast beyond the border of the bladder wall, with filling or pooling of the vaginal canal just beneath the bladder visible on the radiograph. The same applies to a urethrovaginal fistula located proximal to the external sphincter.

Surgical Anatomy

When preparation is made for urethrovaginal fistula repair, it is important, whenever possible, to preserve the periurethral fascia as a separate and distinct layer from the underlying urethral mucosa. In some cases, the periurethral fascia is obliterated around the fistula and dissection proximally, distally, and laterally (Fig. 14-1). Often, one must dissect laterally on either side of the fistula to identify the retracted ends of the periurethral fascia. This layer is critical in achieving a successful repair.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree