6 Vaginal Repair of Enterocele and Apical Prolapse

To view the videos discussed in this chapter, please go to expertconsult.com. To access your account, look for your activation instructions on the inside front cover of this book.

Vaginal vault prolapse can be repaired using a vaginal, abdominal, laparoscopic, and/or robotic approach. Although the focus of this chapter is on transvaginal repair, there are situations in which we feel abdominal sacral colpopexy (open, laparoscopic, or robotic) is preferred. Such cases would include but are not necessarily limited to young women with vaginal vault prolapse, certain women for whom transvaginal procedures have failed, and women with a foreshortened prolapsed vagina. In frail elderly women who are not and do not intend to be sexually active, obliterative procedures, in which the entire vagina is closed, should be considered (see Chapter 9).

Apical prolapse may present as uterovaginal prolapse or posthysterectomy vault prolapse. In the latter an enterocele is usually present. The treatment of uterine prolapse by vaginal hysterectomy is discussed in Chapter 5. Options for apical support are discussed in this chapter. It is also important to remember that apical prolapse frequently occurs in conjunction with anterior and/or posterior prolapse; thus repair of all affected compartments may be necessary. This chapter discusses and demonstrates the various procedures that can be performed transvaginally to correct an enterocele and vaginal vault prolapse.

Anatomy of Apical Support

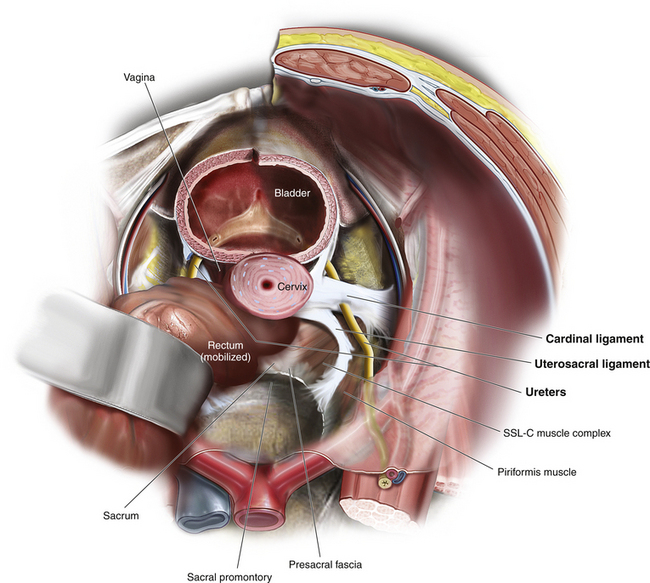

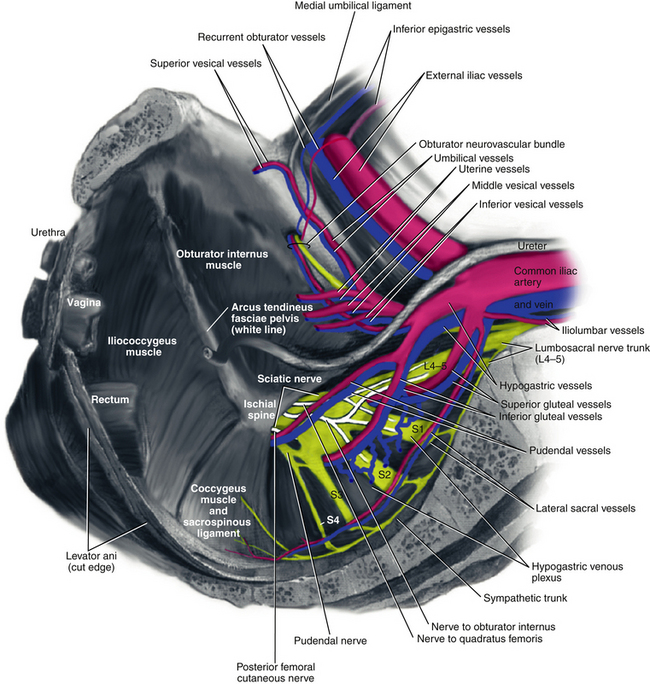

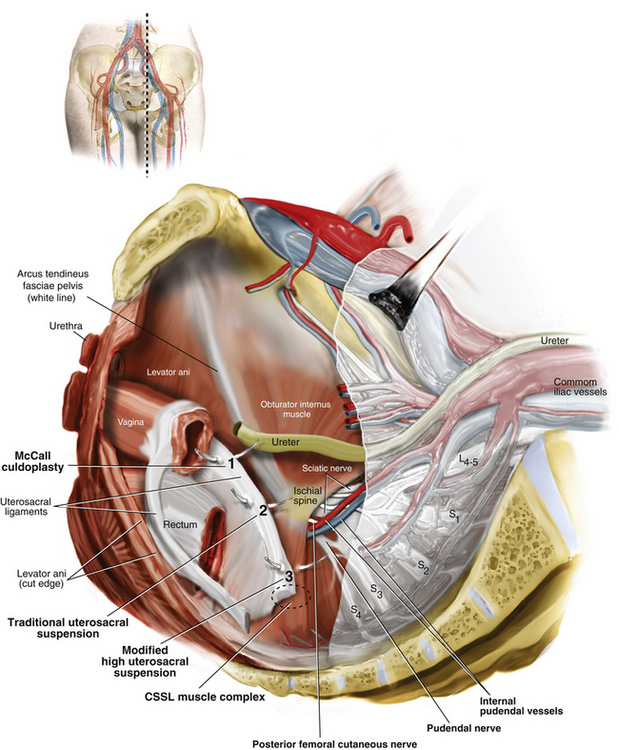

The apex (proximal one third) of the vagina and the uterus are suspended from the pelvic sidewall and sacrum (level I support) by the cardinal ligaments and uterosacral ligaments, respectively (see Fig. 3-1). When these supporting structures become stretched and weakened, apical prolapse occurs. These are thus structures that can be used to repair apical prolapse (e.g., uterosacral ligament suspension or plication, or McCall culdoplasty). Alternatively, other structures such as the sacrospinous ligament may be used as the anchoring point for apical support in a prolapse repair. When these structures are used for repair of pelvic organ prolapse, it is important to understand the anatomy and relationship of other critical structures such as the rectum and ureters as well as nerves and blood vessels that come in close proximity to these structures. Apical repairs are associated with about a 1% to 2% incidence of ureteral injury. Often this is due not to direct injury to the ureter (such as ligation) but rather to kinking of the ureter caused by incorporation of paraureteral connective tissue.

The uterosacral ligaments are fascial condensations that suspend and support the upper vagina and uterus through attachment to the anterior sacrum. They are continuous at points with the cardinal ligaments, which extend to the pelvic sidewall and arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis (ATFP) and also with the paravesical, pararectal, and paravaginal fascia (Fig. 6-1 and Video 6-1 ![]() ). High uterosacral ligament suspension for repair of apical prolapse is based on the concept that these ligaments do not significantly attenuate in cases of uterovaginal or posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse but instead “break” at certain points. The sacrospinous ligament extends from the ischial spine to the sacrum and is covered by the coccygeus muscle. Although it is not normally involved in apical support, it makes a strong anchoring point when an extraperitoneal vault suspension is desired (Fig. 6-2).

). High uterosacral ligament suspension for repair of apical prolapse is based on the concept that these ligaments do not significantly attenuate in cases of uterovaginal or posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse but instead “break” at certain points. The sacrospinous ligament extends from the ischial spine to the sacrum and is covered by the coccygeus muscle. Although it is not normally involved in apical support, it makes a strong anchoring point when an extraperitoneal vault suspension is desired (Fig. 6-2).

Transvaginal Enterocele Repair

Surgical Technique for Transvaginal Intraperitoneal Enterocele Repair

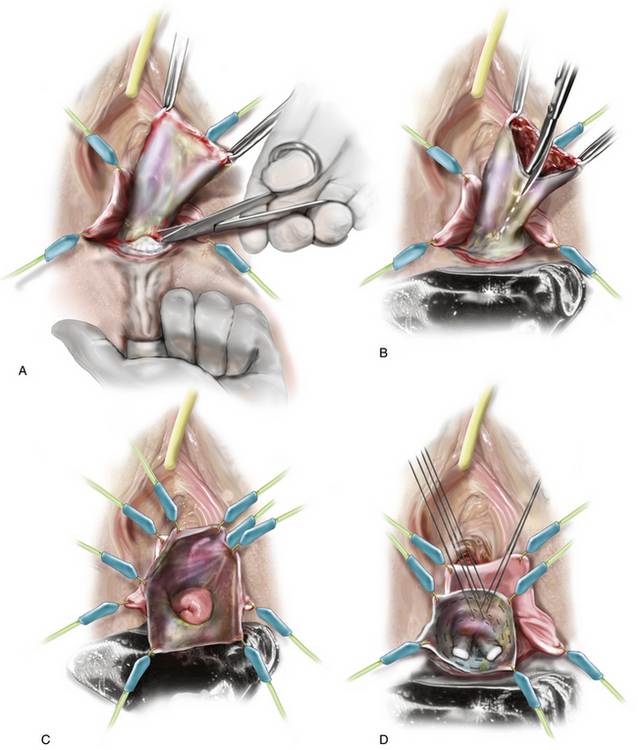

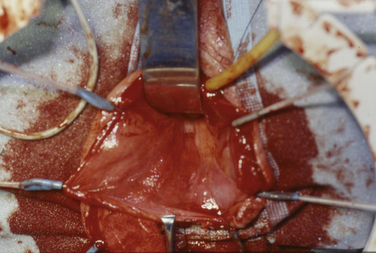

1. The patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position. The first step in an intraperitoneal repair is to isolate the enterocele sac. The prolapsed vaginal wall is grasped with two Allis clamps and brought toward the surgeon. The vaginal wall may be infiltrated with a lidocaine-epinephrine or vasopressin (Pitressin) solution before a longitudinal incision is made in the vaginal wall along the entire length of the enterocele (Fig. 6-3).

2. The vaginal wall is then carefully dissected away from the underlying peritoneal sac. Care is taken to stay very superficial and develop the proper plane with the curve of the Metzenbaum scissors against the vaginal wall. A finger can be placed on the outside of the vaginal wall to stabilize the initial dissection.

3. Once the proper plane is entered, it is usually easy to dissect the vaginal wall away from the underlying sac. Often this can be done with blunt dissection using a moist sponge. However, when the enterocele sac is densely adherent to the vaginal wall, sharp dissection may be required. Care taken here will prevent early entry into the peritoneal cavity. (Note: In cases in which the surgeon plans to augment the anterior repair with a synthetic mesh, extra care must be taken to stay in the proper plane and not to thin the vaginal wall.)

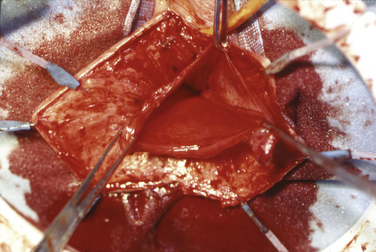

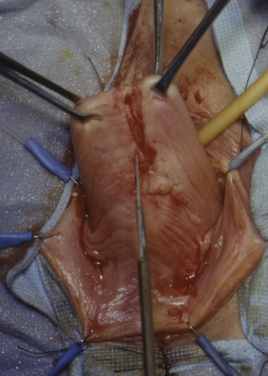

4. The dissection of the enterocele is continued all the way to the neck of the sac anteriorly and posteriorly. A finger can be placed in the rectum to facilitate dissection of the sac off the anterior wall of the rectum (Fig. 6-4, A). After the enterocele has been completely isolated, the sac is opened and the peritoneal cavity is entered (see Figs. 6-4, B and 6-5). At this time, small bowel, omentum, or ovary and fallopian tube may be seen in cases in which previous hysterectomy without oophorectomy has been performed (see Fig. 6-4, C). (See Videos 6-2 and 6-3 for a demonstration of vaginal dissection of an enterocele sac. ![]() )

)

5. The next step is closure of the enterocele defect or Douglas pouch unless a formal high uterosacral suspension is planned, because that procedure itself will obliterate the enterocele as well as suspend the vaginal apex. Retraction of the peritoneal contents is best performed using one or more moist laparotomy pads and a narrow Deaver or Heaney retractor (Fig. 6-6). Placing the patient in the Trendelenburg position so that abdominal organs fall slightly cephalad assists in this step. The enterocele repair begins posteriorly while the abdominal contents are retracted anteriorly using the retractor.

6. A size 0 or 1 polyglycolic acid (PGA)* or polydioxanone (PDS) suture is first placed through the posterior peritoneum and into the prerectal fascia overlying the rectum. A circumferential closure of the defect is then performed by placing the purse-string suture laterally in the right uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex, anteriorly in the peritoneum overlying the base of the bladder, laterally on the left in the uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex, and finally again posteriorly in the peritoneum and prerectal fascia (see Fig. 6-4, D). After this purse-string suture has been placed, a second one may be placed in the identical structures in close proximity to the first. If no further apical repair or suspension will be performed, it is especially important to incorporate the uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex into the closure, because this will be the main support of the vaginal apex. In addition, care should be taken to place these sutures deep enough to ensure that adequate vaginal depth can be achieved. When an additional apical support procedure is performed, the main purpose of the purse-string suture is simply to close the peritoneum.

7. After all sutures are placed, the assistant cinches down and places tension on one of the purse strings while the surgeon ties the other. After the first purse string has been tied, the second purse string (if placed) is tied in a similar manner. The excess enterocele sac may be excised and the ends oversewn with 2-0 PGA suture.

8. Cystoscopy is performed to document that there has been no injury to the bladder. Ureteral injury is ruled out by intravenously administering indigo carmine and observing efflux of blue-tinged urine from the ureteral orifices.

9. If no further apical support or repair of other compartments is to be performed, the vaginal wall may be closed with 2-0 PGA suture. The purse-string sutures can be placed through the apex of the vaginal cuff. If anterior repair and/or apical suspension is to be done, it may be performed at this time.

Figure 6-3 The apex of the vagina is grasped and the vaginal wall is incised for the length of the enterocele.

Video 6-1 demonstrates an enterocele repair in a woman with symptomatic Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) stage III apical prolapse. After this repair is completed, the surgeon has the option of securing the apex of the vaginal cuff to the repair or performing a sacrospinous or mesh-augmented repair.

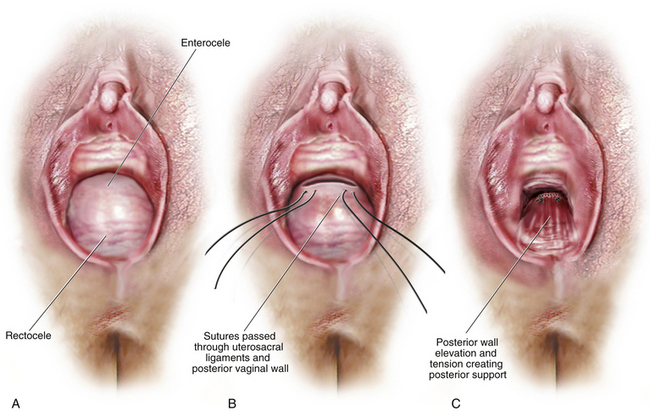

In most cases of enterocele, the vaginal apex is also prolapsed and requires a separate procedure to support it. It is also common for concomitant anterior and posterior defects to be present, and therefore repair of more than one compartment is typically necessary. Several techniques are commonly used to accomplish transvaginal vault suspension, and which technique is best is still debated. Here we review nonaugmented repairs, including uterosacral ligament suspension, sacrospinous ligament fixation, and iliococcygeus fixation, as well as augmented repairs, including sacrospinous ligament fixation with mesh. McCall culdoplasty is described and demonstrated in Chapter 5.

High Uterosacral Vaginal Vault Suspension

Suspension of the vaginal vault to the uterosacral ligaments as initially described by Shull provides a more natural vaginal axis than sacrospinous ligament fixation. The procedure provides good apical support without significantly distorting the vaginal axis, and passage of sutures intraperitoneally can be cleaner and simpler than passage through retroperitoneal structures. A disadvantage of the procedure is that the uterosacral ligament may at times lie in close proximity to the ureter. Studies have shown that the ureter can become kinked when sutures are passed too far laterally. When we first began performing high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension as described by Shull and colleagues, we mobilized the tunica muscularis vaginae off the epithelium and suspended the epithelium and tunica muscularis separately, making sure that sutures were passed through the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. Figure 6-7 illustrates intraperitoneal suture placement for the McCall culdoplasty, the traditional uterosacral suspension, and the modified high uterosacral suspension.

Over time, we realized that this practice led to a shorter vagina—one that, in some cases, was less than ideal for the patient. We began, therefore, to pass sutures through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall only. With this change in technique, we have been able to create a longer vagina—and this has not been at the expense of any increase in the incidence of cystocele or anterior enterocele. Our experience directly contradicts the notion that fascial continuity is necessary for apical prolapse repair to be successful over the long term. This change in technique has also facilitated posterior vaginal wall support (Fig. 6-8). Also we initially thought that a large cul-de-sac needed to be obliterated in the midline with internal McCall-type stitches that are separate and distinct from the uterosacral suspension sutures. We no longer do this routinely because we believe that the numerous sutures that are passed through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, including the peritoneum, effectively obliterate the enterocele and keep down the incidence of recurrent enterocele and high rectocele. Finally, we have come to realize that sutures placed medial and cephalad to the ischial spine are often passed through a portion of the coccygeus muscle–sacrospinous ligament complex (see Fig. 6-7).