Vascular causes

Arteriovenous malformations

Renal hemangioma

Renal vein hypertension

Nutcracker syndrome

Renal arteriovenous fistula

Renal arteriopelvic fistula

Nonvascular causes

Bleeding diathesis

Exercise-induced (“march”) hematuria

Renal papillary necrosis

Endometriosis

Renal ptosis

Renal tuberculosis

Previous retroperitoneal surgery

Unilateral idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis

Loin pain hematuria syndrome

A small number of patients who are evaluated ureteroscopically for hematuria will be found to have transitional cell carcinoma tumor or urolithiasis. In other patients, nothing will be found. Despite no bleeding lesion being found, many studies report successful resolution of the hematuria after ureteroscopy. It has been suggested that this could be due to resolution of unseen venous-caliceal communication because of increased intraluminal pressure during the ureteroscopy or post-procedure inflammation [21, 22]. Results of ureteroscopy for the evaluation and treatment of benign essential hematuria are presented in Table 3.2. Our systematic review of the literature reveals an overall success rate of 90% for the ureteroscopic treatment of patients with benign essential (lateralizing) hematuria [4, 21–33].

Table 3.2

Results with ureteroscopy for lateralizing hematuria (benign essential hematuria)

Study | Findings | Success (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Discrete | Diffuse | Nothing seen | Discrete | Diffuse | Nothing seen | Total | ||||||

Author (first) | Year | N | Mean followup (months) | Hemangioma | Minute venous rupture | Other | ||||||

Gittes | 1981 | 13 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | |||||

Patterson | 1984 | 4 | 5.5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 4/4 | |

McMurtry | 1987 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 5/5 | 1/3 | 6/8 | |

Kavoussi | 1989 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 5/6 | 5/6 | ||

Bagley | 1990 | 32 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 12/13 | 0/4 | 5/5 | 17/22 | |

Kumon | 1990 | 12 | 10.3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9/9 | 9/9 | ||

Desgrandchamps | 1994 | 8 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4/4 | 0/1 | 4/5 | |

Nakada | 1997 | 17 | 60 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 9/11 | 1/3 | 10/14 | |

Tawfiek | 1998 | 23 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 14/14 | 3/3 | 4/5 | 21/22 |

Yazaki | 1999 | 15 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |||||

Mugiya | 1999 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4/4 | 4/4 | |||

Daneshmand | 2002 | 15 | 20.2 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11/12 | 11/12 | ||

Mugiya | 2007 | 23 | 73 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 9/9 | 9/9 | ||

Brito | 2009 | 13 | 26 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13/13 | 13/13 | ||

Mugiya | 2010 | 20 | 16 | 4 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 19/19 | 19/19 | ||

Total | 215 | 64 | 50 | 32 | 34 | 28 | 112/117 (96 %) | 10/16 (63 %) | 10/14 (71 %) | 132/147 (90 %) | ||

Other causes of bilateral benign essential hematuria can be confused with lateralizing hematuria. These include march hematuria or exercise-induced hematuria, a rare condition where repeated impacts to the body (particularly the feet, like when a soldier is marching) can cause hemolysis and subsequent hematuria. Severe march hematuria can lead to athlete nephritis, which is likely caused by the hemoglobin load on the kidney. In children, allergy symptoms can rarely present as unexplained hematuria during allergic flares [34]. Diagnostic ureteroscopy can often be avoided if cystoscopic examination reveals bleeding from both ureteral orifices. These conditions often resolve spontaneously.

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Ureteroscopy Technique

Before performing ureteroscopy, a urinalysis with or without culture should be done to ensure that the urine is free from infection. Prophylactic antibiotics should be given prior to instrumentation of the urinary tract. The primary goal of diagnostic ureteroscopy is clear visual inspection of the entire upper urinary tract. Here we present some techniques that will help achieve this goal.

Bleeding from the urinary tract can occur anywhere from the upper pole of the kidney to the urethral meatus. Endoscopic evaluation of these patients begins with careful cystourethroscopy. Special attention is paid to the prostatic urethra in men, which can be a frequent site of benign gross hematuria. The bladder urothelium is carefully and completely inspected and a bladder lavage for cytology is performed. The next cystoscopic step is careful patient inspection for bloody efflux from the ureteral orifices. When gross hematuria is present, this critical step will allow differentiation of unilateral and bilateral hematuria. Bilateral gross hematuria is likely “nonurologic” and a ureteroscopic evaluation may not be helpful.

Ureteroscopy should be performed in a method that minimizes urothelial trauma prior to visualization, as any trauma could be misinterpreted as a potential cause of hematuria (Fig. 3.1). This includes minimizing guidewire trauma. Some authors have reported performing flexible ureteroscopy without a working or a safety guidewire. Some newer flexible ureteroscopes can be introduced into the ureteral orifice under direct vision without the use of a working guidewire [35]. This technique requires significant expertise and is not possible with all flexible ureteroscopes, in all patients. This technique will likely become less challenging with future generations of ureteroscopes and may soon become the ideal “no touch” method for diagnostic ureteroscopy. However, at this time, it is limited to certain ureteroscopes in the hands of experienced endourologists. For these reasons, we recommend and will review the standard technique of diagnostic ureteroscopy using rigid ureteroscopy and flexible ureteroscopy to inspect the entire upper urinary tract.

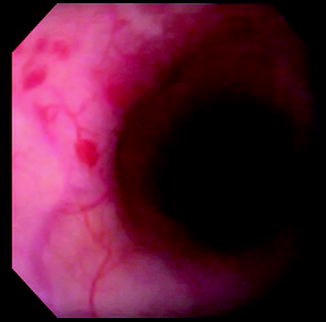

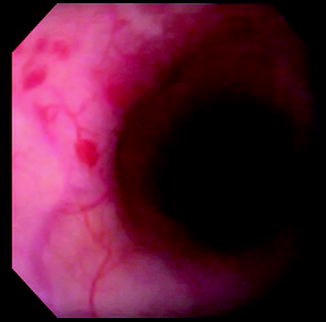

Fig. 3.1

Small area of urothelial abrasion from passage of the ureteroscope. Techniques to minimize this problem will help prevent confusion with potential pathologic lesions

Rigid and flexible ureteroscopy provide complimentary access to the entire upper urinary tract [2]. While rigid ureteroscopy allows direct insertion and easy control of the ureteroscope, it does not allow easy access to the ureter superior to the iliac vessels. Without the ability to deflect the tip of a rigid ureteroscope, inspection of the intrarenal collecting system is impossible. Flexible ureteroscopy provides complete access of the entire intrarenal collecting system and upper ureter. However, inspection of the distal ureter is difficult because of buckling of the ureteroscope into the bladder. For this reason, rigid ureteroscopy is performed below the iliac vessels, and flexible ureteroscopy above. This combination of rigid and flexible ureteroscopy provides complete visual inspection of the entire upper urinary tract. When performing ureteroscopy for the evaluation of hematuria, tumor surveillance, or other diagnostic purposes, it is important to recognize that our standard ureteroscopy technique can produce traumatic lesions that may be mistaken for pathology. Care should be taken to minimize this trauma to the ureter during ureteroscopy, as it will interfere with our diagnostic visual inspection. The effort to minimize trauma begins with using the smallest ureteroscope practical to avoid the need for dilation. Direct insertion of a rigid ureteroscope without prior dilation of the intramural ureter allows clean inspection of the distal ureteral mucosa. Avoiding the use of a guidewire during insertion of the rigid ureteroscope will further minimize trauma to the ureter. If a guidewire is needed to obtain access to the ureter, it should be passed no more than 2–3 cm into the ureter, just enough to obtain adequate access for the ureteroscope. This should be done under direct vision to minimize injury to the orifice. Once access is obtained, the ureter is inspected with the rigid ureteroscope from the ureteral orifice to the level of the iliac vessels, taking care to visualize the full circumference of the ureter. Only the least amount of irrigation that will provide adequate distention of the ureter for visualization should be used. This will prevent over-distention of the ureter and intrarenal collecting system. Even minimal over-distention of the collecting system can lead to small areas of urothelial hemorrhage and render the remaining inspection of the ureter for true sources of bleeding pointless. Once the distal ureter is completely inspected to the level of the iliac vessels, further inspection of the proximal ureter requires flexible ureteroscopy. A guidewire is passed through the rigid ureteroscope, only as high as necessary into the ureter to allow placement of the flexible ureteroscope. Preferably, the guidewire is passed only to the level of the ureter that has been inspected with the rigid ureteroscope. The rigid ureteroscope is removed, leaving the guidewire in place, and the flexible ureteroscope is passed over this guidewire to the proximal extent of rigid ureteroscopic inspection. Flexible ureteroscopic inspection is then performed from this point and proceeds proximally, in a retrograde fashion and is generally done without a safety guidewire. Again, this is to avoid trauma to the ureteral urothelium that might interfere with the diagnostic inspection. When using this technique of diagnostic ureteroscopy, we are inspecting a urothelium that is “untouched” either by guidewires or ureteroscopes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree