Fig. 55.1

Treatment algorithm

As is evidenced by the NCCN guidelines for the treatment of rectal cancer with resectable liver metastasis, there is no defined algorithm for the initial treatment of patients. A useful starting point is to determine whether the patient is symptomatic from the primary tumor in terms of pain, bleeding, obstruction or perforation. If the patient has symptoms then staging studies should be performed to document the extent of liver metastases, whether the rectal primary tumor can be resected with adequate margins and whether extrahepatic spread is present. In these patients surgery is often performed as the initial treatment with either resection of the primary tumor or diversion of the fecal stream. If the patient presents for emergent or urgent operation then liver resection should not be performed at this time due to increased morbidity and mortality [21]. If the patient is stable and undergoes a more elective operation then resection can be considered for patients with limited disease, i.e., less than a formal lobectomy with the intent of not delaying the start of chemotherapy.

The initial treatment of asymptomatic patients should be discussed in the context of a multidisciplinary tumor board with input from medical oncology, radiation oncology, colorectal surgery and hepatobiliary surgery. The decision to begin with a multidrug systemic chemotherapy regimen versus 5-FU/leucovorin and pelvic radiation often is determined by the extent of disease in the pelvis as well as the extent of disease in the liver and whether the planned surgical approach is simultaneous resection, staged resection or a “liver first” approach. Controversy exists over the optimal initial treatment regimen and there are no randomized trials that evaluate outcome.

Advocates of systemic chemotherapy as the initial treatment regimen argue that response to treatment allows for evaluation of tumor biology and helps to select patients that will do best with aggressive surgical therapy [22]. Downsizing large tumors is often possible due to the high response rates with current chemotherapeutic options, and chemotherapy can be interrupted after 2–3 months for a short course of pelvic radiation in patients ultimately undergoing resection [23]. Advocates of 5-FU/leucovorin and radiation as the initial treatment regimen argue this treatment reduces pelvic recurrences, reduces overall morbidity and shortens the length of time required for the patient to reach surgical therapy. In general, only a minority of patients who present with rectal cancer and synchronous liver metastasis are eligible to undergo surgery as their initial treatment modality. Those patients should have disease in the rectum which can be resected with adequate margins, no signs of extrahepatic metastasis and limited liver involvement.

55.4 Management of the Primary Tumor

Resection of the primary tumor is the gold standard treatment for patients rectal cancer. The development and improvement of chemotherapeutic agents and metallic stents have helped spare patients with rectal cancer the morbidity of extensive perineal/pelvic resections. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can help control metastases, reduce the volume and number of SLM and thus modify the type of hepatic resection required. For patients with uncontrollable hepatic disease, in whom surgery poses high risk of mortality and morbidity, chemotherapy can serve as a first line treatment modality. Combination chemotherapy regimens, combined with agents targeted to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or epithelial growth factor (EGF) receptor can downstage patients for resection [24].

Radiotherapy is also a crucial part of preoperative combined modality therapy for RC-SLM. Pelvic radiotherapy is needed to down-stage a non-resectable primary tumor and achieve R0 resection. The German trial CAO/ARO/AIO-94, published in 2003 proved the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Preoperative combined modality therapy (chemoradiotherapy/chemoimmunotherapy) has been widely accepted and mentioned in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines as the standard treatment for locally advanced rectal cancer [25–27]. Radiation doses used are 45–50 Gy in 25–28 fractions. 5-FU based chemotherapy is used concurrently as a radiosensitizer. Recommended preoperative primary treatment includes 2–3 months of (1) (FOLFIRI or FOLFOX or CapeOX) ± bevacizumab or (2) (FOLFIRI OR FOLFOX) ± panitumumab or cetuximab [KRAS wild-type gene only] or (3) Infusional IV 5-FU/pelvic RT or (4) bolus 5-FU/leukovorin/pelvic RT or (5) capecitabine/RT can also be used [26].

It is very important to accurately assess the patient’s response to combined modality therapy (CMT). An unresected primary tumor poses a risk of distressing symptoms or complications and morbidity due to emergency procedures. Patients with a good response to CMT may also have problems with vanishing hepatic metastasis [28]. Re-evaluation for resection should be considered, in otherwise unresectable patients after 2 months of preoperative chemotherapy and every 2 months thereafter [26].

Following removal of the primary tumor, adjuvant systemic therapy contributes to improved survival [29]. Six months of perioperative treatment is preferred. NCCN guidelines suggest the use of infusional IV 5-FU/pelvic RT or bolus 5-FU/leucovorin/pelvic RT or cepacitabine/RT or 5-FU ± leucovorin or FOLFOX or cepecitabine ± oxaliplatin, then infusional 5-FU/RT or bolus 5-FU/leucovorin/RT or capecitabine/RT, then 5-FU ± leucovorin or FOLFOX or capecitabine ± oxaliplatin [26]. In Patients who did not receive preoperative radiotherapy, postoperative pelvic radiotherapy results in a lower rate of pelvic recurrence in patients with RC-SLM when compared with patients that undergo surgery alone [2]. However, increased morbidity in patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy compared to those receiving neoadjuvant therapy makes treatment prior to surgery preferable.

55.5 Management of Synchronous Liver Metastases

Surgical resection for cure is the only possibility to obtain long-term survival and must be considered even if patients have poor prognostic factors [15]. When surgery isn’t possible or in the neoadjuvant setting, chemotherapy plays a major role in reducing the metastatic load on the liver and changing the type of hepatic resection required. Chemotherapy for liver metastasis may be administered systemically or regionally. Trans-arterial chemo-embolization has been effectively used for localized liver lesions. For extensive liver metastasis, systemic chemotherapy or regional chemotherapy by hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) of cytotoxic agents such as floxuridine, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin or irinotecan can be useful [24]. In the neoadjuvant setting, HAI provides significant tumor response but similar or even higher response rates may be obtained by systemic chemotherapy [30]. A trend towards better long term outcomes has been seem with HAI. Following chemotherapy, resectability is determined by location of the lesions, extent of disease and adequate hepatic function [2].

Optimal surgical strategy for RC-SLM patients that present as possible resection candidates, is still debatable. Traditionally, patients have undergone a two-staged procedure with resection of the primary tumor followed by chemotherapy and subsequent liver resection [3]. In this strategy various treatment regimens of chemotherapy can be employed. NCCN guidelines suggest 2–3 months of preoperative chemoradiotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy. Another standard of care is chemoradiotherapy using 5-FU and leucovorin given concurrently with radiation over 5 weeks, and then 6–10 weeks after the last dose of radiotherapy, patients undergo rectal surgery. If no complications occur, SLM is treated as early as 3 months after rectal surgery. However, the mean delay between resection of the primary tumor and subsequent resection of the liver metastasis is 6 months [31]. Sauer et al., demonstrated that up to 50 % of patients do not receive optimal treatment after rectal surgery because of postoperative complications [27]. Some patients may be undertreated because postoperative morbidity doesn’t allow achievement of the complete treatment, and because of the psychological effect of long-term of treatment, leading some patients to refuse complete management [4]. A staged procedure is sometime required due to complications of the primary neoplasm such as bowel obstruction or colonic perforation, and the need for extensive hepatic resection. Staged resection may also be required due to late referral after the primary tumor was resected [15].

Advancement in anesthesia and operative techniques have made it possible to simultaneously resect the primary tumor and liver secondaries in RC-SLM, with low mortality and acceptable morbidity. Similar surgical outcomes have been reported after two-staged and simultaneous resections, that included major hepatectomies or requiring resection of multiple hepatic segments [32]. It also has potential benefits in terms of quality of life and cost [33–35]. Until recently, the eligibility for simultaneous resection was restricted to right colon tumors or a limited number of metastases [36, 37]. Criteria for selection used in a recent publication included fitness for anesthesia, expected R0 resection of the primary tumor, no unresectable extrahepatic disease and adequate predicted volume of hepatic remnant post resection [3].

Groups have also reported simultaneous laparoscopic resection (SLR) of rectal carcinoma and SLM [38, 39]. Such a procedure is considered after discussion with colorectal and liver surgeons for R0 resection and adequate laparoscopic exposure of metastatic liver lesions [39]. The inclusion criteria for such a procedure includes a rectal tumor fit for anterior resection with end-to-end anastomosis, number of liver lesions ≤2 and absence of a history of abdominal operations [38]. A complicated or advanced rectal lesion, liver lesions adjacent to major vessels or in the caudate lobe would exclude SLR [39]. Preservation of abdominal wall, better compliance, shorter hospitalization, early resumption of social activities, good cosmetic results are some of the advantages of a totally laparoscopic procedure. Another important role of such a technique is in the context of a two-staged hepatectomy in case of rectal cancer with bilobar or extensive SLM. The second stage hepatectomy may be easier owing to less adhesions from the totally laparoscopic first surgery [40–42]. During a simultaneous laparoscopic resection, the colorectal resection is usually done first but if there is a large blood loss during liver surgery or if Pringle’s maneuver is anticipated, then liver resection may be performed first. This will be less harmful to the anastomosis because it will be made after the possibility of high mesenteric pressure, lowered intestinal perfusion and the possibility of major blood loss has passed [39].

Mentha et al., first described the “liver first” approach in patients with colon and rectal cancers with advanced SLM [42]. This approach has also been used in patients with advanced rectal cancer with SLM [31]. De Jong et al., described their 5 year experience with “liver first” procedures and found that it was feasible in approximately four-fifths of their patients [43]. In the Liver first approach, patients are primarily treated with neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy. If there is no progressive disease, a laparotomy is performed with the intention of performing resection of liver metastases. After successful resection of liver metastases, patients are treated with neoadjuvant radiotherapy (with or without chemotherapy) for the primary rectal tumor. Four weeks after the end of neoadjuvant radiotherapy, imaging is performed to check for unresectable metastases. If none are found, rectal resection is performed 8–10 weeks after the last radiotherapy dose [31].

The rationale behind the “liver first” approach is to control the SLM at the same time as the rectal primary and allow unhurried chemotherapy before rectal surgery when indicated. Removing all known liver metastases at the first surgical intervention protects the patients from progression of liver metastases when the patient is receiving radiotherapy for the rectal primary tumor and may improve the patient’s state of mind when dealing with long term treatment of cancer. However, with this approach, response to chemotherapy cannot be assumed to persist. There is a possibility of progression after initial response and an intervention in the rectum as early as 2–4 weeks from chemotherapy may be required. In addition, the use of Irinotecan and Oxaliplatin as neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy may produce chemotherapy associated steatosis and venous outflow problems which can render liver surgery more difficult and hazardous [42].

In the presence of extensive liver tumor burden, future liver remnant becomes a major factor in the planning for a hepatectomy. Historically, portal vein embolization has been used to assist with growth of the future liver remnant. The procedure involves either ligation of the portal vein in segments planned for resection or coil embolization performed by interventional radiologists. In patients with high likelihood of low future liver remnant, PVE results in hypertrophy of the unresected segment, thus resulting in better functional hepatic reserve. Traditionally, portal vein embolization served as a bridge between resections in a two-staged hepatectomy. Portal vein embolization (PVE) is also a useful tool to achieve resectability in extensive or bilobed lesions. The patient undergoes preoperative PVE of the segments to be resected. One month after PVE, repeat imaging is done to assess hypertrophy and surgery is performed.

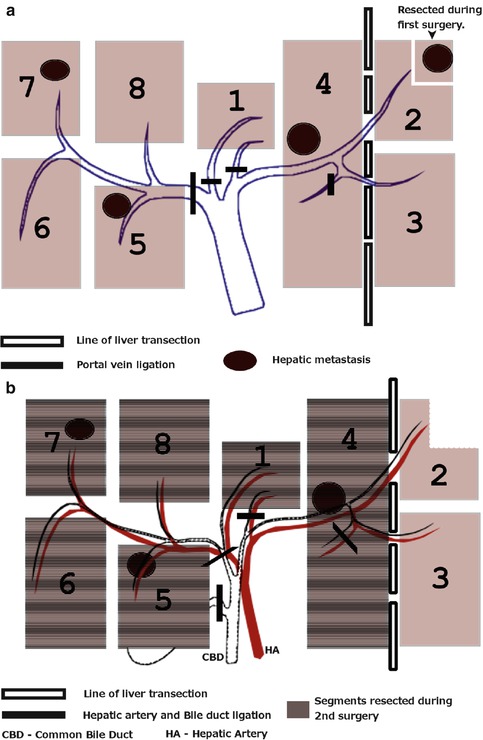

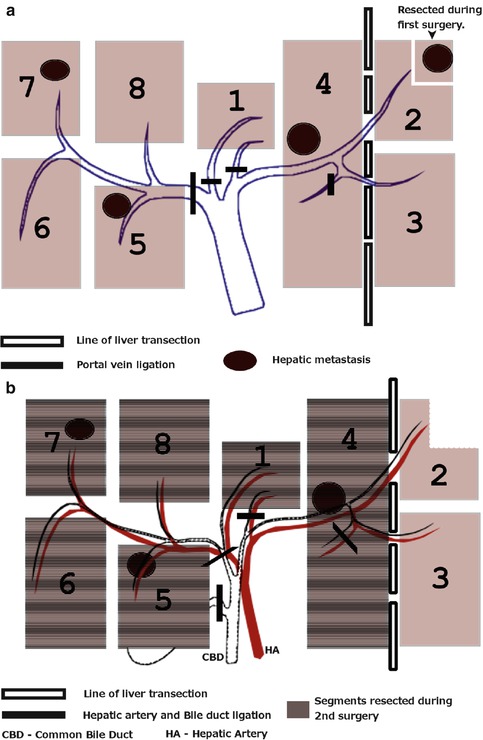

Baumgart et al., described a new two-step technique for obtaining adequate parenchymal hypertrophy in patients requiring extended hepatic resection with limited functional reserve [44] (Fig. 55.2). Known as the ALPPS (Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy) approach, this two-step procedure consists of ligation of portal veins to the segment planned to be removed. In order to ligate intrahepatic portal collaterals, the liver parenchyma is divided in situ. This induces accelerated hypertrophy in the remaining segment. Devascularization of segments prevents neovascularization and interlobar perfusion. This induces a median hypertrophy of 74 % in a very short time frame. After an interval of 6–12 days (median 9 days), the resection is completed [44–46]. Recently, this entire procedure has also been completed laparoscopically [47].

Fig. 55.2

(a) ALPPS—step 1, (b) ALPPS—step 2

55.6 Follow Up

Surveillance for a patient with RC-SLM includes history and physicals every 3–6 months for 2 years, then every 6 months for a total of 5 years; CEA levels every 3–6 months for 2 years, then every 6 months for a total of 5 years; chest/abdominal/pelvic CT annually for up to 5 years; colonoscopy in 1 year with a repeat in 1, 3, 5 years [26]. The most common site of recurrence is the liver remaining after the resection [5]. Adjuvant systemic therapy contributes to improved survival. All patients undergoing liver resection should receive intense follow-up and adjuvant chemotherapy [6]. Recent studies suggest follow up for 10 years for late recurrences [48].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree