13 Treatment of Obstruction Following Stress Incontinence Surgery

To view the videos discussed in this chapter, please go to expertconsult.com. To access your account, look for your activation instructions on the inside front cover of this book.

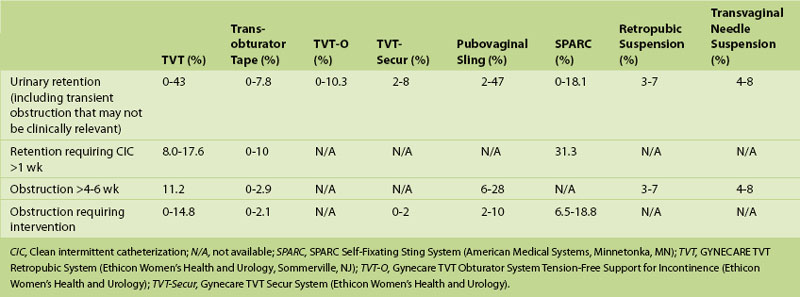

Because of greater public awareness, more and more women are actively seeking treatment for stress urinary incontinence (SUI). This increase, combined with the availability of newer surgical techniques associated with less morbidity, has led to a rise in the use of surgery to treat SUI and a concomitant increase in the number of patients with postoperative voiding problems. The true incidence of voiding dysfunction and iatrogenic obstruction after SUI surgery is likely unknown and probably underestimated because of underdiagnosis, misdiagnosis, variations in definition, and underreporting. Reported rates of obstruction vary depending on the type of surgery performed (Table 13-1). Urinary obstruction requiring intervention will occur in at least 1% to 2% of patients after any SUI surgery, even when performed by an experienced surgeon.

Voiding dysfunction following SUI surgery is related to obstruction, detrusor overactivity, or impaired contractility. Iatrogenic obstruction is most commonly the result of technical factors. With sling procedures, obstruction is usually caused by excessive tension on the sling around or under the urethra. The sling can also become dislodged and displaced from the intended position, producing obstruction. During retropubic urethropexy, sutures placed medially can lead to urethral deviation or periurethral scarring resulting in obstruction. Sutures placed distally can cause kinking of the urethra with resultant obstruction and an inadequately supported bladder neck or proximal urethra, and potentially lead to continued SUI. “Hypersuspension” or overcorrection of the urethrovesical angle can also result from excessive tightening of the periurethral sutures. Vaginal prolapse that is not recognized and corrected at the time of sling surgery can also lead to obstruction via kinking or external compression. Learned voiding dysfunction with failure of external sphincter relaxation after surgery can produce functional obstruction. Finally, impaired contractility can be responsible for a relative obstruction.

Transient voiding dysfunction and urinary retention are common after certain SUI surgeries (e.g., traditional procedures like pubovaginal sling). Because of this, it is difficult to determine the appropriate timing of evaluation and intervention for suspected obstruction following such SUI procedures. Traditionally evaluation was delayed for at least 3 months after surgery. This practice was based on the literature on pubovaginal sling placement, colposuspension, and needle suspension, which indicated that recurrent SUI following intervention could be minimized by waiting at least 90 days before evaluation of obstructive symptoms because spontaneous resolution of symptoms commonly takes 3 months. However, the waiting period that was advocated after these traditional procedures has largely been abandoned for retropubic, transobturator, and single-incision synthetic midurethral sling procedures. Because of the immobility and contraction of the mesh as well as in-growth of fibroblastic tissue at 1 to 2 weeks, patients with retention or severe symptoms are less likely to improve beyond this period. After retropubic and transobturator tape procedures, temporary voiding dysfunction has been reported to resolve in 25% to 66% of patients in 1 to 2 weeks and in 66% to 100% of patients by 6 weeks. Based on these data and our experience, waiting beyond 6 weeks for workup and intervention seems unwarranted. Some would also argue that because up to 66% of patients can be expected to experience resolution of their symptoms within 2 weeks, workup and possible intervention are warranted at the 2-week mark or earlier (in cases of complete inability to void) after discussion with the patient about her symptoms, level of bother, and willingness to risk possible intervention. In our practice, if a patient is unable to void spontaneously (i.e., has urinary retention) within 1 week after a retropubic or transobturator tape procedure, we will consider and discuss loosening the sling in cases in which simultaneous pelvic organ prolapse repair was not done.

Loosening of a Synthetic Midurethral Sling

In women with postoperative urinary retention following synthetic midurethral sling procedures, some surgeons advocate early intervention within 7 to 14 days after surgery. After placement of synthetic midurethral slings (retropubic, transobturator, and single-incision slings) the vast majority of patients should be able to void spontaneously within 72 hours. Early sling loosening can be performed in a minimally invasive procedure under local anesthesia in the office setting or operating room. Early sling loosening is recommended only for women who are dependent on catheterization to empty the bladder.

Surgical Technique for Synthetic Sling Loosening in the Acute Setting (7 to 14 Days After Surgery)

1. Place the patient in the lithotomy position and prepare the vagina in a sterile fashion.

2. Infiltrate the anterior vaginal wall with local anesthetic.

3. Cut the suture used to close the vaginal wall and open the prior incision.

4. Identify the sling and hook it with a right-angle or other small clamp.

5. Spread the clamp or apply downward traction to loosen the tape 1 to 2 cm.

6. If the sling cannot be loosened, cut it in the midline.

Incision of a Biological or Synthetic Sling

Important considerations include the following:

1. Confirm the type of sling in place. If a synthetic sling was used, the brand will determine the color of the sling, and this knowledge can help identify the sling type.

2. Obtain adequate exposure. An inverted-U incision provides the best exposure for a pubovaginal sling, but a midline incision can also be used. A retractor such as a Lone Star will aid exposure.

3. The sling should be identified and isolated. It may be encased in scar or may be under significant tension and difficult to identify. Careful dissection is required to identify the sling. A cystoscope or sound may be placed into the urethra with upward retraction to expose the sling by isolating the axis of tension and indention on the urethra. Some biological slings may not be identified because of autolysis. In such cases the surgeon may proceed to urethrolysis. All synthetic slings must be definitively identified.

Surgical Technique for Sling Incision

1. Cystoscopy is performed to assess the urethra and rule out erosion or urethral injury.

2. An inverted-U or midline incision is made to expose the area of the bladder neck and proximal urethra.

3. Careful dissection is performed to isolate the sling. Injury to the urethra can be avoided by beginning the dissection distally to identify normal urethra and then proceeding proximally to identify and isolate the sling. It should be kept in mind that when there is no urethral erosion, in most cases the sling will be superficial to the periurethral fascia.

4. Usually the sling is isolated in the midline. However, if the sling is extremely tight, it can be isolated lateral to the urethra to avoid urethral injury.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree