Fistulas manifest frequently in Crohn disease and can result in significant morbidity and often lead to the need for surgical intervention. Historically, it has been more difficult to obtain complete fistula closure in patients with perianal Crohn disease. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha agents and the use of more accurate imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging and rectal endoscopic ultrasound have enhanced the ability to manage fistulizing Crohn disease. A combined medical and surgical approach usually presents the best option for most patients.

Crohn disease can manifest in many different ways including fibrostenotic (stricturing) or nonperforating, nonstricturing (inflammatory) disease or predominantly perforating (fistulizing) disease. Patients with fistulizing Crohn disease tend to have a more aggressive disease course. Fistulas can be either external (enterocutaneous or perianal) or internal, such as enteroenteral or enterocystic. The morbidity is increased greatly in those patients with fistulizing disease. Perianal disease and fistulas can lead to fecal incontinence, abscess formation, and anal strictures. External fistulas, including enterocutaneous and perianal fistulas, are associated with pain, abscesses, and drainage. In contrast, internal fistulas are frequently asymptomatic and therefore hard to diagnose. The treatment of fistulas depends on many factors, including location, severity, and previous surgical history.

Understanding of perianal disease continues to grow, and newer therapies such as antitumor necrosis factor anti-(TNF) agents have expanded therapeutic treatment options and changed the practitioner’s goal of treatment for fistulas from reduction in fistula drainage to true closure or fibrosis of the fistula tract.

The estimated incidence of fistulas (enterocutaneous or perianal) in patients with Crohn disease is approximately 35%. Approximately 21% of patients with Crohn will have perianal fistulas within 10 years of diagnosis. Before the introduction of biologic agents, most fistulas required surgical intervention, and the rate of fistula recurrence was estimated to be 34%. Internal fistulas are often silent but perhaps just as common. In a study by Michelassi and colleagues, one third of all patients undergoing an operation for Crohn disease were found to have internal fistulas. Of those patients, 25 of 36 (69%) with enterovesicular fistula had symptoms of internal fistula such as pneumoturia or fecaluria. In the other 147 patients with internal fistulas, only 54% had accurate preoperative diagnostic evaluation (radiographic or endoscopic).

Understanding the anatomy and pathogenesis

Current understanding shows that fistulas in Crohn disease develop secondary to multiple causes. Internal fistulas, or fistulas from the small bowel or colon to the adjacent bowel or organs, are likely secondary to transmural inflammation of the bowel wall. This inflammation then can penetrate into adjacent organs, tissue, or skin. These fistulas are more likely to occur at the site of a stricture and may represent a bypass tract. These types of fistulas are categorized by their location and the connection with contiguous organs such as enterovesicular fistulas or enteroenteric fistulas. One proposed mechanism for perianal fistula formation is that fistulas begin as an ulcer within the anal canal. When feces are forced into this ulcer, they cause penetration of the lesion through the wall. This track then extends over time with increased pressure from the fecal stream. Another hypothesis of fistula formation involves an abscess of one of the anal glands, which can be present within the intersphincteric space. This abscess then grows, and a fistula forms as a way to drain this area of the purulence under pressure. The fistula can extend through the external anal sphincter (trans-sphincteric fistula), track down to the skin (intersphincteric fistula), or track upward to become a suprasphincteric fistula. It is important to diagnose and categorize fistulas correctly, as correct categorization impacts which treatment modality will be most useful or successful in an individual patient.

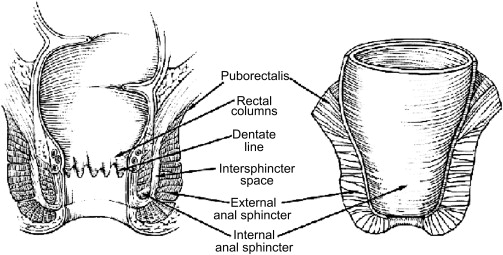

In order to understand how best to treat fistulizing Crohn disease, one must have a thorough understanding of the anatomy of the anal canal ( Fig. 1 ). The anal canal is formed by three layers:

The internal anal sphincter, which is made of smooth muscle of the rectum

The intersphincteric space

External anal sphincter, which is comprised of skeletal muscle arising from an extension of the puborectalis and levator ani muscles

The dentate line is the midway point of the internal anal sphincter. It is the area that marks the interface of the columnar and transitional epithelium of the rectum from the squamous epithelium of the anus. Within this area, one finds the anal crypts with anal glands located at the bases of the crypts.

A careful physical examination and endoscopic examination must be performed prior to initiating treatment for the fistulizing disease, with special attention to location of the fistula in relation to the dentate line. Fistulas can be classified many different ways. The most anatomically precise method is the Parks classification. This classification system uses the external sphincter as a central point of reference and includes five types of perianal fistulas: (1) intersphincteric, (2) trans-sphincteric, (3) suprasphincteric, (4) extrasphincteric, and (5) superficial. An intersphincteric fistula tracks between the internal anal sphincter (IAS) and the external anal sphincter (EAS) in the intersphincteric space. A trans-sphincteric fistula tracks from the intersphincteric space through the EAS. A suprasphincteric fistula leaves the intersphincteric space over the top of the puborectalis and penetrates the levator muscle before tracking down to the skin. An extrasphincteric fistula tracks outside of the EAS and penetrates the levator muscle into the rectum. Finally, a superficial fistula tracks below both the IAS and EAS complexes.

Although the Parks system is the most accurate method of describing fistula anatomy and helps clinicians communicate with the surgeons taking care of patients with perianal fistulas, there are several limitations to this system, including the fact that associated abscesses and connections to other structures such as the vagina or bladder are not part of this schema but are clinically important.

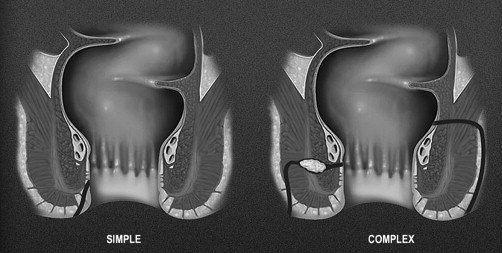

The other methods for classifying fistulas are to divide them into simple or complex fistulas. This was proposed in 2003 by American Gastroenterological Association Technical Review Panel as an alternative and more clinically relevant classification system for perianal fistula ( Fig. 2 ). Within this system, a simple fistula is superficial or begins low in the rectal canal, has a single opening on the skin, is not associated with an abscess, and does not connect to other structures such as the vagina or scrotum. A fistula is complex if it begins high in the canal, is associated with an abscess, has multiple openings, or connects to an adjacent structure. Another important distinction is to determine if the fistula is associated with obvious inflammation of the colonic mucosa. If so, this too would be considered complex. This classification is clinically relevant, because complex fistulas involve more of the sphincter complex, reducing the chance for fistula healing, and placing patients at increased risk for incontinence with aggressive surgical intervention.

Diagnostic modalities for assessing fistulas

Occult abscesses or fistulas are difficult but important to recognize. Missing occult lesions can result in recurrent fistulas or abscesses or convert a simple fistula into a complex fistulizing process. Once the fistulizing process becomes complex, the chance for healing is reduced greatly. In order to prevent the development of a complex fistula and increase the chance of closure, one must identify and optimize the medical and surgical treatment early at disease onset. The fistula must be defined fully so appropriate therapy can be started. The goal is to establish drainage of any abscess that may be present and control fistula healing to prevent abscess formation during treatment of fistulas. Ideally, this initial assessment could be done with a simple digital rectal exam (DRE), although because of the associated induration and scarring, the accuracy of this examination in defining fistula anatomy is reportedly low, 62% in one study.

Because of the low accuracy of the DRE, imaging should be used as a means to provide a therapeutic roadmap to ensure that all potential areas are treated. The various imaging modalities that have been used to assess perianal fistulas include fistulography, computed tomography (CT), pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and rectal endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).

Diagnostic modalities for assessing fistulas

Occult abscesses or fistulas are difficult but important to recognize. Missing occult lesions can result in recurrent fistulas or abscesses or convert a simple fistula into a complex fistulizing process. Once the fistulizing process becomes complex, the chance for healing is reduced greatly. In order to prevent the development of a complex fistula and increase the chance of closure, one must identify and optimize the medical and surgical treatment early at disease onset. The fistula must be defined fully so appropriate therapy can be started. The goal is to establish drainage of any abscess that may be present and control fistula healing to prevent abscess formation during treatment of fistulas. Ideally, this initial assessment could be done with a simple digital rectal exam (DRE), although because of the associated induration and scarring, the accuracy of this examination in defining fistula anatomy is reportedly low, 62% in one study.

Because of the low accuracy of the DRE, imaging should be used as a means to provide a therapeutic roadmap to ensure that all potential areas are treated. The various imaging modalities that have been used to assess perianal fistulas include fistulography, computed tomography (CT), pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and rectal endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).

Fistulography and CT

Fistulography involves the placement of a small catheter into the cutaneous opening of a fistula tract and injection contrast under pressure. Fistulography can cause pain during the examination and the theoretical potential for dissemination of septic fistulous contents. Fistulography has a low overall accuracy for determining the tract of the fistula, ranging from 16% to 50%.

CT has been used to assess perianal disease but is limited by poor spatial resolution in the pelvis. It is not commonly used, because its accuracy also is low, ranging from 24% to 60%.

EUS MRI

The most accurate way to evaluate perianal Crohn fistulas is by MRI or rectal EUS. A prospective blinded study compared the accuracy of MRI, EUS, and examination under anesthesia (EUA) in 34 patients with suspected Crohn perianal fistulas. In this study, all three methods demonstrated high accuracy when compared with the consensus gold standard (EUS, 91%; MRI, 87%; and EUA, 91%). The consensus gold standard was determined by the coinvestigators after reviewing all of the test results and the patients’ history. When any of the imaging modalities were combined with EUA, the accuracy was 100% in these patients and was the most cost-effective approach. The role of MRI and EUS to monitor the fistula response to medical therapy is still being explored but may help guide treatment decisions in these patients.

Treatment options

After a fistula has been assessed properly and categorized as simple versus complex, the most appropriate treatment course can be determined. The decision between medical therapy and surgical therapy or a combination medical and surgical therapy is determined by the type of fistula and the degree of rectal inflammation present.

Medical treatment

Antibiotics

Multiple studies have been performed utilizing antibiotics for treating fistulizing Crohn disease, with only modest results. Most of these are open-label case series involving few patients. Antibiotics are used for both their activity in perianal sepsis and for their anti-inflammatory properties. The most common antibiotics used are metronidazole at doses of 750 to 1000 mg/d or ciprofloxacin at 1000 to 1500 mg/d for up to 2 to 4 months. Adverse events commonly associated with metronidazole include metallic taste, glossitis, nausea, and a distal peripheral sensory neuropathy. Adverse events with ciprofloxacin occur less commonly but include headache, nausea, diarrhea, and rash.

Recently, a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial was performed looking at ciprofloxacin and metronidazole for treating perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn disease. Twenty-five patients were randomized to ciprofloxacin 500 mg (10 patients), metronidazole 500 mg (7 patients), or placebo (8 patients) twice daily for 10 weeks. Response (at least 50% reduction in the number of draining fistulas) at week 10 was seen in four patients (40%) treated with ciprofloxacin, one patient (14.3%) treated with metronidazole, and one patient (12.5%) with placebo ( P = .43). One patient each from both the ciprofloxacin and placebo groups, and five (71.4%) treated with metronidazole dropped out of the study ( P <.02). This small study suggested that remission and response occurred more often in patients treated with ciprofloxacin, but the differences were not significant.

Immunomodulators

There have been several trials of 6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine (AZA/6MP) for luminal Crohn disease where the treatment of perianal disease was a secondary endpoint. A meta-analysis of these trials looked at fistula closure as a secondary endpoint for post hoc analysis. This analysis found that 22 of 42 (54%) of patients with perianal Crohn disease who received AZA/6MP responded versus only 6 of 29 (21%) patients who received placebo (odds ratio [OR] = 4.44) Caution should be taken, as the primary goal of these studies was to treat active inflammatory Crohn disease, and they were not designed primarily to look at the effect on perianal fistulas. In fact, only one of the studies stratified the patients for the presence of fistulas at randomization.

In a study by Dejaco and colleagues, antibiotics were used along with immunomodulator therapy. The use of metronidazole or ciprofloxacin induced an early response (at least 50% reduction in the number of draining fistulas) at week 8, with fistula closure occurring in 25% of cases. In patients who received additional azathioprine therapy, the response was better (48% vs 15%) at week 20. Most of the patients in this study had simple fistulas, and only 9 of the 52 cases were classed as complex fistulas.

Tacrolimus

Tacrolimus has been studied for perianal Crohn disease in a randomized placebo-controlled study. Forty-eight patients with Crohn perianal fistulas were randomized to tacrolimus standard dose 0.2 mg/kg/d versus placebo for 10 weeks. In the tacrolimus group, 43% had fistula improvement (closure of at least 50% of fistulas for longer than 4 weeks) compared with 8% placebo patients ( P = .004). Complete fistula closure, however, was only achieved in 10% of the patients who received tacrolimus. Fistula closure in the treatment group was not improved with concomitant immunosuppressive therapy with AZA/6MP (38% closure with therapy vs 50% without). The number of adverse events was higher in the treatment group (5.2 vs 3.9, P = .009), including headache, insomnia, elevated creatinine, paresthesias, and tremor. The use of tacrolimus requires regular monitoring of renal function and drug levels, which limits its ease of use.

In the study by Gonzalez-Lama, tacrolimus was used to treat patients with fistulizing Crohn disease that was refractory to conventional therapy including infliximab. In this open-label study, patients received oral tacrolimus (0.05 mg/kg every 12 hours). Ten patients were included in the study (enterocutaneous fistula, three patients; perianal fistula, four patients; rectovaginal fistula, three patients) with 6 to 24 months of follow-up. Four patients (40%) achieved complete clinical responses. Five patients (50%) achieved partial responses (decrease in fistula drainage, size, discomfort) ( P <.05).

Cyclosporine

Studies with cyclosporine for fistulizing Crohn disease also have been performed. These are all uncontrolled small studies that showed improvement in fistula drainage, but most patients relapsed after transition to oral therapy or discontinuation of the drug. The toxicity profile of cyclosporine may preclude use for fistulizing disease given safer, better-tolerated alternatives. Methotrexate also has been studied in an uncontrolled case series for treatment of perianal Crohn disease ; however, there currently are not enough data to support use of methotrexate for fistulizing disease.

TNF antagonists

Prior to the introduction of anti-TNF antibodies, the goal of treatment was primarily control of symptoms in order to improve the patient’s quality of life. Long-term resolution had not been demonstrated in a large group of patients. Now it is realistic to strive for complete fibrosis of the fistula when using biologic agents, especially in those patients with simple fistulas.

Several biologic therapies have been developed for treating Crohn disease—including adalimumab (a fully human immunoglobulin [Ig]G1 anti-TNF-alpha monoclonal antibody), infliximab (a chimeric monoclonal antibody to TNF-alpha), and certolizumab pegol (a humanized anti-TNF Fab’ monoclonal antibody fragment linked to polyethylene glycol)—which antagonize TNF-alpha and have been shown to decrease clinical severity of disease.

There have been two double-blind placebo-controlled trials of an anti-TNF antibody with a primary focus being on fistulizing Crohn disease. Both of these trials have been with infliximab. The initial fistula trial with an anti-TNF-alpha agent looked at the short-term effect of infliximab on fistula drainage. Ninety-four patients were randomized to treatment with infliximab 5 mg/kg, infliximab 10 mg/kg, or placebo. Patients were given an infusion at weeks 0, 2, and 6. The primary endpoint was a greater than or equal to 50% reduction from baseline in the number of draining fistulas. A fistula was considered to be draining if the examiner could express purulent material with gentle pressure on the fistula tract. Results showed a 68% response rate (achievement of the primary endpoint) in the 5 mg/kg infliximab treatment arm compared with only 26% in the placebo cohort; 55% of patients who received infliximab 5 mg/kg had complete cessation of drainage (ie, closure) of all fistulas. The fistulas, however, tended to become active again once infliximab was discontinued.

This study led to the ACCENT II (A Crohn Disease Clinical Trial Evaluating Infliximab in a New Long-term Treatment Regimen in Patients With Fistulizing Crohn Disease) trial, which investigated whether cessation of fistula drainage could be preserved over the course of a year with infliximab maintenance therapy given every 8 weeks. Patients who had active fistulas and who responded to the initial three doses of infliximab at weeks 0, 2, and 6 were randomized to receive infliximab or placebo every 8 weeks. After 54 weeks, 36% of patients in the infliximab group maintained complete fistula closure compared with 19% in the placebo arm ( P = .009).

Fistula healing was studied as a secondary endpoint in the adalimumab maintenance trial, CHARM (Crohn trial of the fully Human antibody Adalimumab for Remission Maintenance). The CHARM trial assessed the efficacy of adalimumab in maintaining response and remission in patients with luminal Crohn disease. Complete fistula closure at 56 weeks was seen in 33% of the treated group (ie, total randomized population on therapy who had fistulas at baseline, combined 40 mg weekly and every other week adalimumab dosing arms) compared with 13% in the placebo arm ( P = .016). The response was very durable. In patients who demonstrated fistula closure at week 26, all maintained fistula closure at week 56. Recently, the results of an open-label extension study continued from the end (week 56) of the CHARM trial were presented. The study population was comprised of patients with fistulas at baseline of CHARM; data from the two adalimumab doses were pooled. In this follow-up study, the 2-year complete fistula response rate was 71%, and the 2-year complete cessation of drainage rate was 60%.

Unlike other monoclonal antibodies, certolizumab pegol does not contain an Fc portion and therefore does not induce in vitro complement activation, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, or apoptosis. Fistula healing also was examined as a secondary endpoint in one of the certolizumab maintenance trials (PRECISE [Pegylated antibody fragment Evaluation in Crohn disease Safety and Efficacy] 1). In the subset of patients with a baseline C-reactive protein level greater than or equal to 10 mg/L, certolizumab was shown to be equivalent to placebo in healing fistulas after 26 weeks of therapy; 30% of certolizumab-treated patients had fistula closure verssus 31% of placebo patients.

Conversely, the second certolizumab trial, PRECISE 2, which evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of certolizumab in the maintenance of clinical response following successful induction therapy in patients with active Crohn disease, had a small number of patients with draining fistulas at enrollment. Fourteen percent of patients in the intention-to-treat population from this study had draining fistulas at baseline (28 patients in the treatment arm and 30 on placebo). Among these patients, 54% of those treated with certolizumab had fistula closure as compared to 43% of those in the placebo group. At week 26, 67% of patients who received continuous certolizumab were able to maintain complete fistula closure. The study was underpowered to examine the efficacy of certolizumab for fistula closure. Based on the results above, the authors suspect that certolizumab pegol is effective in fistulizing disease; however, given the conflicting results, further studies are needed to look at the efficacy of certolizumab pegol for treating Crohn perianal fistulas.

There are no head-to-head trials comparing the efficacy of these agents in treating Crohn disease or for obtaining fistula closure. Additionally, there are no studies comparing the efficacy of surgical treatment alone with combination surgical intervention plus conventional medical treatment (antibiotics, immunosuppressants). A retrospective study involving 32 patients with perianal fistulizing Crohn disease, however, examined the efficacy of infliximab alone versus infliximab as an adjunct to seton placement. Patients with fistulizing Crohn disease who had EUA with seton placement prior to receiving infliximab had an initial response of 100% versus 82% for patients who only received infliximab (response was defined as complete closure and cessation of drainage from the fistula). Patients who received infliximab after EUA with seton placement also had a lower recurrence rate (44% vs 79%) and longer time to recurrence (13.5 months vs 3.6 months). In another retrospective review, Topstad and colleagues showed that seton placement prior to infliximab resulted in complete response in 67% of patients.

Natalizumab, a recombinant, humanized monoclonal antibody to alpha-4 integrin, which inhibits leukocyte adhesion and migration into inflamed tissue, has demonstrated efficacy in reducing the clinical severity of Crohn disease. It does not appear to be useful in fistulizing disease, however. On the basis of the initial double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by Ghosh and colleagues, natalizumab did not appear to be effective in fistulizing Crohn disease. The subsequent evaluation of natalizumab as continuous therapy (ENACT)-1, ENACT-2, and efficacy of natalizumab in Crohn disease response and remission trials specifically excluded patients with active fistulas. Therefore, this biologic agent cannot be recommended for patients with fistulizing Crohn disease.

Much has been learned about the treatment of fistulizing Crohn disease since the initial infliximab trials nearly a decade ago. Data indicate that most patients with fistulizing disease will need maintenance therapy, as brief exposure to TNF antagonists does stop drainage of fistulas initially, but reoccurrence is common after cessation of therapy. Indeed, after 1 year of maintenance therapy with infliximab, complete closure of fistula tracks is rare, as evidenced by evidence on MRI or EUS examination of persistent fistula activity even when the fistula drainage stops.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree