The past decade has seen an alarming increase in the burden of disease associated with Clostridium difficile . Several studies have now demonstrated an increasing incidence of C difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with a more severe course of disease compared with the non-IBD population. This article summarizes the available literature on the impact of C difficile infection on IBD and discusses the various diagnostic testing and treatment options available. Also reviewed are clinical situations specific to patients with IBD that are important for the treating physician to recognize.

The past decade has seen an alarming increase in the burden of disease associated with Clostridium difficile . Studies from North America have demonstrated a doubling of incidence during this time period. The estimated economic costs associated with C difficile infection (CDI) range from $436 million to $3 billion in the United States annually. Initially considered to play a key role in the development of antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis, C difficile is now known to cause a wide range of disease presentations ranging from asymptomatic carriage to fulminant colitis, toxic megacolon, sepsis, multiorgan failure, and death. Recent antibiotic exposure or hospitalization were previously considered key in the acquisition of CDI but recent data suggest an increasing number of CDI not associated with antibiotic use and infections being acquired in the community.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD; Crohn disease [CD], ulcerative colitis [UC]) are chronic, lifelong, immunologically mediated inflammatory disorders of the gut that present typically with symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, or rectal bleeding. Several studies have now demonstrated an increasing incidence of CDI in patients with IBD with a more severe course of disease compared with the non-IBD population. The similarity in symptoms between the two conditions (CDI and an IBD flare) but markedly divergent treatment plans (specific-antibiotic therapy and potential reduction of immunosuppression for CDI in the setting of IBD compared with escalation of immunosuppressive therapy for an IBD flare) makes it essential for treating physicians to be aware of the impact of CDI on patients with IBD, have a high index of suspicion, and institute early diagnostic testing and appropriate therapy to ensure optimal outcomes.

This article summarizes the available literature on the impact of CDI on IBD and discusses the various diagnostic testing and treatment options available. Also reviewed are clinical situations that may be specific to patients with IBD that are important for the treating physician to recognize.

Pathogenesis of CDI

Clostridium difficile is a gram-positive spore-forming anaerobe that exerts its effect on tissue through active toxin production. There are two toxins associated with C difficile (toxin A and toxin B), which are coded by the tcd A and tcd B genes, respectively. These loci are located on a 19.6-kg base locus, the pathogenicity locus. The toxins act by binding to receptors on the enterocyte with subsequent endocytosis. This leads to pore formation, which further facilitates intracellular entry of the toxins. This is followed by glycosylation of Rho and Ras proteins leading to disruption of the epithelial cytoskeleton. As a result, there is loosening of the intercellular tight junction, increasing secretory losses, and voluminous diarrhea. In addition, toxin A also exerts a cytotoxic effect. Although most of the strains causing CDI produce both toxins A and B, a small fraction of CDI is caused by strains that either produce toxin A (11% of infections) or toxin B alone (7% of infections). Up to six other toxins are produced by C difficile . Important among these is a recently identified toxin, the binary toxin, which may be associated with more severe disease. The exact role of the binary toxin in the pathogenesis of CDI has not yet been defined.

NAP1/027 Epidemic Strain of Clostridium difficile

Between 2002 and 2005, outbreaks of CDI were identified in the province of Quebec, Canada. The strain of C difficile associated with these outbreaks demonstrated greater virulence than previously described strains. Over 150 ribotypes of CDI have been described so far. This epidemic strain of hypervirulent C difficile was identified to be the BI/NAP1/027 strain (restriction-endonuclease analysis group BI; pulsed-field gel electrophoresis type NAP1 [North American pulsed-field gel electrophoresis type 1]; and polymerase chain reaction ribotype 027). This strain carries the binary toxin in addition to producing 16 times the amount of toxin A and 23 times the amount of toxin B compared with typical strains. This epidemic strain has also been identified subsequently from several countries, forming an increasingly important cause of regional outbreaks of C difficile . The specific impact of this epidemic strain on patients with IBD is still unknown. Bossuyt and colleagues in examining the rising IBD-associated CDI in their institution did not find it to be disproportionately caused by the epidemic strain, but did not describe a prevalence of BI/NAP/027 ribotype among all their cases of CDI.

Prevalence of CDI in patients with IBD

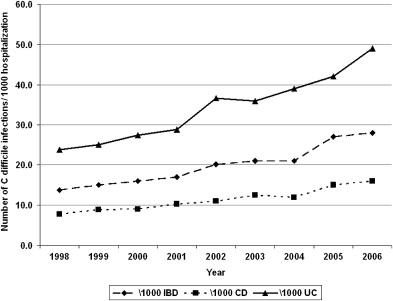

Two decades ago C difficile was believed to be an infrequent infectious complication in patients with IBD. More recent reports have noted higher rates of infection, however, but more importantly, a rising temporal trend in CDI complicating the course of patients with IBD across several institutions and study populations. Rodemann and colleagues in a single center retrospective study identified a doubling of the incidence of CDI in patients with CD (from 9.5 to 22.3 per 1000 admissions) and a tripling in incidence among UC patients (from 18.4 to 57.6 per 1000 admissions) from 1998 to 2004. At the Medical College of Wisconsin, the authors identified a similar rise in the proportion of C difficile cases complicating IBD from 1.8% in 2004 to 4.6% in 2005. The data from these single-center reports have been corroborated by larger studies using nationwide representative hospitalization population sampling in the United States. In a study using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Nationwide Inpatient Sample from the United States, Ananthakrishnan and colleagues identified similar increases in CDI complicating hospitalization for IBD occurring nationally (UC, from 24 per 1000 to 39 per 1000; CD, from 8 per 1000 to 12 per 1000) between 1998 and 2004. Extending this study to 2006 reveals a continuing increase in the proportion of IBD hospitalizations being complicated by CDI ( Fig. 1 ). The similar frequency estimates in the previously mentioned single-center and national studies suggest that the issue of CDI complicating hospitalizations in patients with IBD is widespread and not restricted to specific hospitals, tertiary referral centers, or regions within the United States.

Although these studies used the entire United States inpatient IBD cohort as the denominator in calculating the rates of infection, the frequency of C difficile complicating disease course in IBD patients who present with typical symptoms of colitis or disease flare, such as diarrhea and rectal bleeding, is much higher. Early reports found CDI infrequently in this population. Rolny and colleagues identified C difficile in only 5% of patients admitted for a flare. Subsequent reports placed the frequency of CDI between 5% and 18% among patients presenting with disease flare. More recently, among 99 patients who were admitted to Mount Sinai hospital with symptoms of a UC flare and had stool testing for C difficile toxin, 47% were positive, emphasizing the importance of a having a high index of suspicion for CDI in IBD patients presenting with typical symptoms. Adult IBD patients are not the only cohort impacted by C difficile . A recent study from Italy identified C difficile in 24.7% of patients with diarrhea or abdominal pain from within their pediatric IBD cohort. Although most studies on C difficile in IBD have focused on the hospitalized population, the prevalence of C difficile identified through stool culture was as high as 8.2% in an asymptomatic outpatient IBD cohort. Whether this represents asymptomatic colonization or has true disease-modifying effect by affecting the future disease course of IBD is still unclear. The rising frequency of CDI complicating IBD has paralleled the alarming increases in C difficile seen in the non-IBD population. In some institutions, the rate of increase of C difficile in the younger, healthier patients with IBD has outpaced that in the older non-IBD population with a greater comorbid burden, a traditionally higher-risk cohort.

Prevalence of CDI in patients with IBD

Two decades ago C difficile was believed to be an infrequent infectious complication in patients with IBD. More recent reports have noted higher rates of infection, however, but more importantly, a rising temporal trend in CDI complicating the course of patients with IBD across several institutions and study populations. Rodemann and colleagues in a single center retrospective study identified a doubling of the incidence of CDI in patients with CD (from 9.5 to 22.3 per 1000 admissions) and a tripling in incidence among UC patients (from 18.4 to 57.6 per 1000 admissions) from 1998 to 2004. At the Medical College of Wisconsin, the authors identified a similar rise in the proportion of C difficile cases complicating IBD from 1.8% in 2004 to 4.6% in 2005. The data from these single-center reports have been corroborated by larger studies using nationwide representative hospitalization population sampling in the United States. In a study using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Nationwide Inpatient Sample from the United States, Ananthakrishnan and colleagues identified similar increases in CDI complicating hospitalization for IBD occurring nationally (UC, from 24 per 1000 to 39 per 1000; CD, from 8 per 1000 to 12 per 1000) between 1998 and 2004. Extending this study to 2006 reveals a continuing increase in the proportion of IBD hospitalizations being complicated by CDI ( Fig. 1 ). The similar frequency estimates in the previously mentioned single-center and national studies suggest that the issue of CDI complicating hospitalizations in patients with IBD is widespread and not restricted to specific hospitals, tertiary referral centers, or regions within the United States.

Although these studies used the entire United States inpatient IBD cohort as the denominator in calculating the rates of infection, the frequency of C difficile complicating disease course in IBD patients who present with typical symptoms of colitis or disease flare, such as diarrhea and rectal bleeding, is much higher. Early reports found CDI infrequently in this population. Rolny and colleagues identified C difficile in only 5% of patients admitted for a flare. Subsequent reports placed the frequency of CDI between 5% and 18% among patients presenting with disease flare. More recently, among 99 patients who were admitted to Mount Sinai hospital with symptoms of a UC flare and had stool testing for C difficile toxin, 47% were positive, emphasizing the importance of a having a high index of suspicion for CDI in IBD patients presenting with typical symptoms. Adult IBD patients are not the only cohort impacted by C difficile . A recent study from Italy identified C difficile in 24.7% of patients with diarrhea or abdominal pain from within their pediatric IBD cohort. Although most studies on C difficile in IBD have focused on the hospitalized population, the prevalence of C difficile identified through stool culture was as high as 8.2% in an asymptomatic outpatient IBD cohort. Whether this represents asymptomatic colonization or has true disease-modifying effect by affecting the future disease course of IBD is still unclear. The rising frequency of CDI complicating IBD has paralleled the alarming increases in C difficile seen in the non-IBD population. In some institutions, the rate of increase of C difficile in the younger, healthier patients with IBD has outpaced that in the older non-IBD population with a greater comorbid burden, a traditionally higher-risk cohort.

Risk factors for CDI

Environmental Risk Factors

Environmental exposure is the most common route of acquisition of CDI, which is frequently the result of person-to-person transfer of infectious spores. Exposure to a health care environment including recent hospitalizations increases the risk for nosocomial acquisition of CDI, the most common source of infection. Health care personnel are both at a greater risk for acquisition of infection and potentially transferring infection between patients if appropriate infection control measures are not followed.

Prior antibiotic exposure remains a key risk factor for the acquisition and development of CDI. Emerging data suggest, however, it no longer remains the only or even a necessary risk factor. Clindamycin was the antibiotic initially associated with CDI but since then multiple other antibiotics have been identified to confer a higher risk for CDI. These more commonly include broad-spectrum antibiotics, particularly fluoroquinolones, but the risk is not restricted to any specific antibiotic class. C difficile has even been described during the use of such antibiotics as vancomycin and metronidazole, agents typically used to treat CDI. The mechanism through which antibiotic use seems to increase the risk for CDI may be through the disruption of the normal intestinal flora and a subsequent proliferation of C difficile , a more resistant organism. Antibiotic use seems to be less essential for development of CDI in the IBD population. Antibiotic use within 3 months before CDI was seen in only 40% of IBD patients compared with 69% in the non-IBD population in one study, whereas another study was not able to identify any recent antibiotic exposure in 39% of IBD patients developing C difficile.

Immunosuppression is another well-recognized risk factor for acquisition of C difficile with greater frequency of CDI recognized in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy or patients with organ transplantation on immunosuppression. Being chronic immunologically mediated inflammatory diseases, both CD and UC require long-term immunosuppressive therapy in a significant proportion of patients. Issa and colleagues identified maintenance immunosuppression to be associated with twofold risk of CDI (odds ratio [OR] 2.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.28–5.12), a finding corroborated by a second study from Belgium. One other study failed to demonstrate this association, but may have been limited by a small sample size. Aminosalicylates (5-aminosalicylic acid compounds, such as mesalamine) have not been associated with CDI.

Other potential offending drugs that have been proposed include gastric acid suppressive therapy, such as with proton pump inhibitors. Some initial studies demonstrated a higher risk of development of CDI with proton pump inhibitor therapy but this finding has not been universally demonstrated. Recent studies of CDI in IBD populations also did not confirm this association of proton pump inhibitors with CDI.

Nosocomial or health care associated–infection is the most common modality of acquisition of CDI. Several recent studies in IBD population have shown, however, that a significant proportion of CDI in this cohort is community acquired. Lack of recent health care environment should also not deter the treating physician from suspecting CDI.

Host Risk Factors

Increasing age and greater comorbid burden increase the risk of CDI in the IBD and non-IBD populations. IBD patients who develop CDI tend to be younger, however, than the corresponding non-IBD population who develop CDI. Nguyen and colleagues from an analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample demonstrated a 13% greater risk of CDI with each 1 point increase in the Charlson’s comorbidity burden index. In addition to immunosuppressive medication, host immunity may play a role in determining susceptibility to CDI with patients who are able to mount a greater antibody response against the toxin being less likely to develop overt disease.

IBD-specific Risk Factors for CDI

Recent studies have shown that underlying IBD itself seems to be a risk factor for the development of CDI. Among IBD patients, involvement of the colon (compared with small bowel disease) seems to be a risk factor for CDI. Several studies have documented a greater rate of C difficile complicating UC compared with CD. Issa and colleagues identified colonic involvement in nearly 93% of IBD patients with CDI; on multivariate analysis, colonic disease conferred threefold greater risk (OR 3.12; 95% CI, 1.28–5.12) for CDI. Among CD, patients within colonic involvement seem to be at a greater risk for CDI than those with isolated small bowel disease. Also, among the subgroup of patients with colonic disease, left-sided or pancolonic involvement is more frequently complicated with CDI than those with limited colonic involvement. This suggests that extent of colonic disease may also be an additional risk factor. Patients with a greater disease activity may also be at a higher risk for CDI. Whether this elevated risk in colonic IBD is attributable to the extent of disruption of the mucosal barrier, alteration in gut flora, or other mechanisms has not yet been well defined. Because most studies on this topic have been retrospective, it has been difficult to tease out whether these associations represent true causation and are risk factors, or actually represent a consequence of the CDI complicating IBD. Further prospective studies are essential to identify if there are any IBD-specific risk factors that may increase the risk for CDI.

Clinical features

Symptoms and Signs

CDI typically presents with symptoms of diarrhea, lower abdominal pain, and tenderness. Although CDI itself presents with voluminous, watery diarrhea without gross blood or mucous, in the setting of underlying active IBD colitis overt rectal bleeding may not be infrequent. Patients may also have systemic symptoms, such as fever, malaise, and anorexia, and in the right setting these symptoms should raise suspicion for C difficile in the absence of an alternative explanation, even if diarrhea is not a prominent symptom. Laboratory evaluation may reveal leukocystosis with left shift; anemia (caused by bleeding or chronic inflammation); or hypoalbuminemia. Stool microscopy can reveal the presence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and is also essential to rule out other bacterial or parasitic causes of diarrhea.

The frequency and impact of asymptomatic carriage of C difficile in patients with IBD remains under investigation. Between 1% and 4% of healthy adults may carry C difficile. In a study of 122 outpatients with quiescent, mild IBD not on immunosuppression, Clayton and colleagues identified asymptomatic carriage of C difficile (by stool culture) in 8.2% of the cohort; this was statistically higher than the rate in their control population of healthy volunteers. They identified no clinically evident CDI during a follow-up of 6 months, but whether the same lack of clinical CDI holds true in patients with greater severity of underlying IBD including those on maintenance immunomodulatory or biologic therapy has not yet been defined and merits future investigation.

Radiologic Evaluation

Radiologic evaluation is not required in most patients with CDI but it can be an important tool to aid in the assessment of complications of severe CDI. Plain abdominal radiography or abdominal CT scans may demonstrate colonic dilatation, wall thickening, or overt perforation and free air in those with complications or severe CDI, with CT scans being the more sensitive of the two modalities. Abdominal imaging can also help in the diagnosis of toxic megacolon or reveal alternative etiology to the patients’ symptoms, such as partial small bowel obstruction or internal penetrating disease.

Endoscopy

Lower gastrointestinal endoscopic evaluation is a key modality for assessment of CDI. The classic endoscopic appearance of CDI, described in about 50% of patients, is the pseudomembrane formation caused by sloughing and necrosis of the mucosa with ulceration. Histologic examination of this pseudomembrane may reveal a “volcano” lesion, focal ulceration with an eruption of necrotic debris and inflammatory cell infiltrate through the area of ulceration. The use of endoscopy in differentiating active colitis related to IBD from CDI has remained disappointing, however, because of the lack of typical features of pseudomembranous colitis in many patients with CDI associated with IBD. Both Issa and colleagues and Bossuyt and colleagues identified no pseudomembranes in any of the IBD patients with CDI who underwent endoscopic evaluation. In the right clinical scenario, the absence of pseudomembranes on lower gastrointestinal endoscopy should not deter the treating clinician from entertaining the diagnosis of CDI in IBD patients. Given the low discriminatory power of endoscopy in distinguishing active IBD colitis from CDI, the authors do not tend to evaluate patients endoscopically solely for the purpose of diagnosis CDI. In patients with fulminant disease, endoscopic evaluation may help objectively assess disease activity and look for other complicating infections, such as cytomegalovirus colitis. In this situation, the authors also obtain stool samples for C difficile toxin testing using suction and a collection trap.

Diagnosis of CDI

The diagnosis of CDI relies on the demonstration of the organism by stool culture or the identification of the toxins in the stool. The most commonly performed and widely available test for C difficile is the stool ELISA for toxins A and B. Although the first-generation ELISA tests detected only toxin A, more recent ELISA tests detect both toxins. This has improved sensitivity because in a small group of patients, CDI is caused by strains producing only toxin B. A minimum of 100 to 1000 pg of either toxin is required for detection by ELISA. The false-negative rate is between 10% and 20% with some studies demonstrating sensitivity as low as 66%.

Stool culture is the most sensitive method for the identification of C difficile and is the gold standard but fails to differentiate toxin-producing from nontoxigenic strains. It requires additional testing for toxins A and B with either cell cytotoxicity assays or ELISA. In addition, it has a prolonged turnaround time of 48 hours and is not widely available. Stool cultures have the advantage of allowing for antibiotic susceptibility testing and molecular typing (especially in outbreak investigations). Cell cytotoxicity assays have sensitivity and specificity approaching 98% and detect much lower levels of toxin than the ELISA. Similar to stool culture, however, they too require significant laboratory support and have a turnaround time of 24 to 48 hours precluding their widespread adoption in routine clinical practice.

It is also important for the treating clinician to recognize the need for testing of multiple consecutive samples because a single sample, particularly with ELISA, may fail to have adequate sensitivity to diagnose CDI. In the authors’ experience, the initial stool ELISA for toxins A and B identified only 54% of cases with the second, third, and fourth specimens identifying 75%, 78%, and 92% of cases, respectively.

Complications and outcomes

Short-term Outcomes

Important and life-threatening complications of CDI include toxic megacolon, colonic perforation, and peritonitis with sepsis. Complicating the clinical picture, many patients who acquire CDI may do so during prolonged hospital stays and have significant underlying comorbid illness, contributing to the higher risk of death associated with CDI.

There are now several single-center and nationwide studies defining the short-term impact of CDI on patients with IBD. Although some studies found shorter hospital stays related to CDI in IBD compared with non-IBD patients, in contrast other studies found similar or longer duration of hospitalization among IBD patients with CDI compared with those with isolated CDI or IBD-related hospitalizations. In one study, CDI-IBD was associated with a 3-day longer hospital stay compared with IBD hospitalizations not complicated by C difficile (3 days; 95% CI, 2.3–3.7 days) and $11,406 higher adjusted hospitalization charges.

Studies have reported varying rates of colectomy for CDI in the setting of IBD. One study reported low rates for urgent or semiurgent colectomy after CDI (1 of 15 patients). Jodorkovsky and colleagues, however, found a 23% rate of emergent colectomy in their CDI-UC population with the indications being toxic complications (4 of 11) or medically refractory disease (7 of 11). This rate was higher than in the C difficile –negative IBD population. In the authors’ center, the rate of colectomy in hospitalized IBD patients with CDI was similarly high at 45% in 2004, but decreased to 25% in 2005 despite similar rates of requirements for hospitalization. Analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample corroborated these single-center studies demonstrating that underlying IBD was associated with sixfold (OR 6.6; 95% CI, 4.7–9.3) greater risk of bowel surgery compared with patients with CDI without underlying IBD.

Long-term Outcomes

Despite this information on the short-term outcomes of IBD patients with CDI, there are far more limited data on the long-term outcomes following CDI in IBD patients. A report from Mount Sinai hospital demonstrated worse outcomes in IBD patients with associated CDI for as long as 1 year after the initial infection, although this study was limited by its inability to tease out recurrent CDI versus a true change in the behavior of underlying IBD. In the previously mentioned study, UC patients with CDI had a significantly higher number of hospitalizations for UC-related causes (58 vs 27; P = .001) or emergency room visits at 1 year following the initial hospitalization for C difficile . They also had a twofold (OR 2.38; 95% CI, 1.01–5.6) higher risk for colectomy at 1 year. At the authors’ institution, they performed a case-control study comparing the disease course for 1 year before and 1 year after the initial infection in 81 patients with IBD who developed C difficile. They found that the mean difference in hospitalizations between the year prior and the year following CDI was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.51–1.27). Forty patients (46%) had at least one more hospitalization in the year following C difficile infection (range 1–9) compared with the year prior. Over half the patients with IBD and CDI required an escalation in the medical therapy for IBD after treatment of C difficile (46 patients, 52.9%). This included new initiation of biologic therapy (23 patients); escalation of current biologic (seven patients); escalation or initiation of azathioprine and 6-MP (10 patients); or methotrexate (six patients). There were 10 documented cases of recurrent C difficile documented by positive toxin assay in this cohort.

The limitations of these retrospective studies remain, however, specifically in teasing out if underlying disease severity is a confounding factor, predisposing to these worse outcomes. It remains undefined whether more severe IBD is associated with acquisition of C difficile and subsequent CDI, although the study by Issa and colleagues indirectly suggested that the use of maintenance immunosuppression and potentially more severe illness was associated with the development of CDI. Likewise, it is unknown if CDI itself truly exerts a disease-modifying effect in patients with IBD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree