Fig. 30.1

Overall survival rates for patients treated with or without adjuvant pelvic radiation therapy for low-intermediate-risk or high-intermediate-risk endometrial cancer on Gynecologic Oncology Group trial GOG-99 (Reprinted from Keys et al. [11], Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier)

The authors of these trials discouraged the use of adjuvant radiation therapy, particularly for patients with low-intermediate-risk disease, for whom the acute and late effects of radiation could not be justified by the negligible benefit. In addition, analysis of recurrence patterns demonstrated that the greatest difference between the treatment arms of these trials was a higher rate of vaginal recurrences, some of which were cured with salvage radiation therapy.

Several studies have evaluated whether vaginal cuff irradiation alone could prevent local recurrences without the added morbidity of pelvic irradiation. A Norwegian trial conducted during the 1970s [8] demonstrated no survival difference in a comparison of pelvic irradiation with vaginal cuff irradiation only. However, the overall favorable profile of the patients and subsequent changes in staging, histologic classification, and treatment technique make it difficult to generalize the results of this trial. Two recent trials revisited this question [12, 13]. In both studies, overall survival was similar for patients treated with pelvic radiation therapy and those treated with vaginal radiation therapy, but as for earlier trials, the power to detect differences was limited by the favorable risk profile of the patients entered. PORTEC-2 [12] was intended to limit enrollment to patients with high-intermediate-risk disease. However, post-analysis pathologic review again demonstrated that patients had much more favorable disease than anticipated, and the event rate was similar to that for PORTEC-1. A second recent trial [13] had approximately twice as many endometrial cancer-related deaths in patients treated with vaginal brachytherapy only, but this was balanced by a higher number of intercurrent deaths in the pelvic radiation therapy arm in a trial that had few events overall.

In summary, available data clearly demonstrate that patients who have low-risk disease (minimally invasive grade 1 and 2 disease) rarely if ever require adjuvant treatment after hysterectomy. Patients with intermediate-risk disease have a vaginal recurrence risk that ranges between 5 and 20 %, depending on the individual findings. These patients may benefit from adjuvant vaginal cuff radiation treatment. Adjuvant irradiation undoubtedly reduces the risk of local recurrence in higher-risk patients; however, available trials do not provide sufficient information about the influence of pelvic irradiation on survival to permit generalizable conclusions. Data from PORTEC-1 [10] indicate a strong correlation between grade and vaginal recurrence risk, which may be >20 % for grade 3 tumors, even minimally invasive ones. These data, combined with the relatively poor salvage rate for high-grade vaginal recurrences [15], provide a strong rationale for giving at least vaginal radiation therapy even for minimally invasive grade 3 tumors. Results of GOG-99 [11] suggest that pelvic radiation therapy may improve survival for patients with high-intermediate-risk disease, but high-quality trials focused on this group are still needed to answer this question with confidence. In the meantime, many practitioners continue to consider pelvic radiation therapy to be standard for patients with high-intermediate-risk disease.

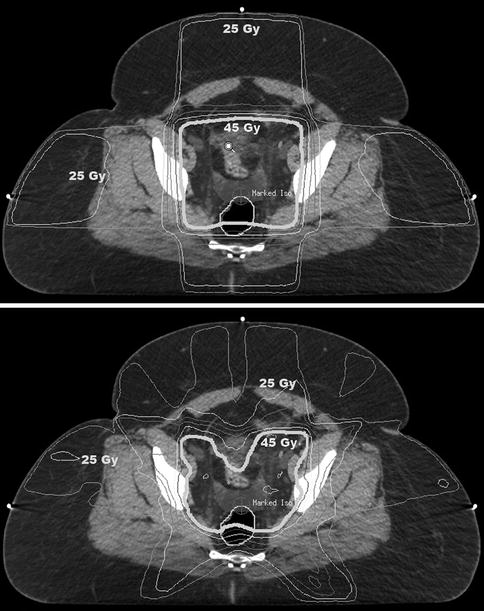

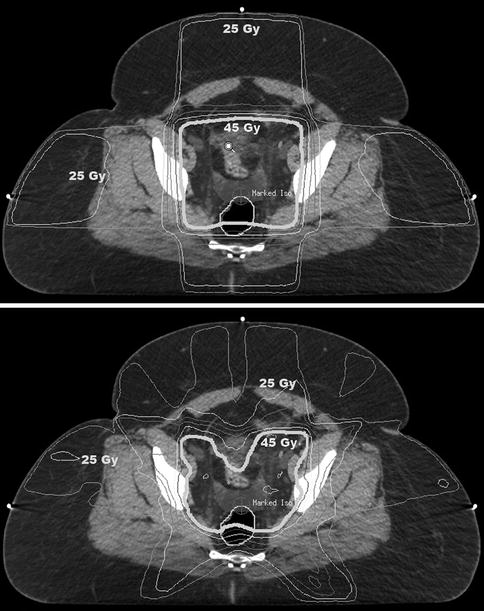

In all cases, the decision to treat should be made after weighing the risks and benefits for an individual patient. For patients whose tumor grade and depth of invasion indicate borderline risk, other risk factors, such as lymph-vascular space invasion and large tumor size, may suggest a greater risk of recurrence and margin for improvement with adjuvant treatment. On the other hand, previous lymphadenectomy (particularly through an open approach) increases the risk of postirradiation complications, and if no positive lymph nodes were found, this probably indicates a decreased likelihood of benefit from pelvic irradiation. Patients who have very thin body habitus, history of pelvic infection, or heavy smoking may have a greater risk of postirradiation complications, shifting the risk-benefit ratio. However, modern radiation therapy techniques that reduce the dose to central pelvic structures (Fig. 30.2) may reduce short- and long-term side effects and increase the potential for gain with adjuvant radiation therapy.

Fig. 30.2

Radiation isodose distributions in a patient treated with postoperative pelvic radiation therapy for high-intermediate-risk endometrial cancer. The top image shows the dose distribution achieved using a traditional four-field technique. The bottom image shows the dose distribution achieved using an intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) technique. With IMRT, central pelvic structures receive a lower dose of radiation, as do peripheral soft tissues

30.4 Adjuvant Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy for Patients with High-Risk Disease

In discussions of the prognosis of patients with endometrial cancer, the term “high risk” is usually used to designate a group that includes patients with FIGO stage III disease (e.g., having involvement of lymph nodes, uterine serosa, adnexa, or vagina). Some trials have included patients with positive peritoneal cytology, although this is no longer considered to be an important independent predictor of prognosis. Sometimes patients with serous cancers or deeply invasive grade 3 cancers are included in the high-risk category. Some trials have admixed high-risk patients with those having advanced disease (stage IV) or high-intermediate-risk disease. The heterogeneity and variable definitions of this category complicate interpretation of trials that evaluated the roles of radiation therapy and chemotherapy in the management of high-risk cancers.

Before 2006, pelvic radiation therapy was generally considered to be the standard treatment for patients with high-risk disease, and the prevailing opinion was that chemotherapy had a very limited role in the adjuvant treatment of uterine cancer. However, in that year, the Gynecologic Oncology Group published the results of GOG-122 [16], the first major trial that compared adjuvant chemotherapy alone with adjuvant radiation therapy. That trial randomly compared adjuvant doxorubicin and cisplatin with adjuvant whole-abdominal radiation therapy (Table 30.1) in patients with “high-risk” disease. The eligibility criteria were very broad—patients who had stage III or IV disease after total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were eligible if they had no evidence of hematogenous or extra-abdominal disease, had no residual disease >2 cm in diameter, had reasonable performance status, and had received no prior chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Although patients were supposed to have surgical staging, many did not undergo node dissection. Tomographic imaging was not routinely performed before or after surgery to verify the completeness of surgical resection. When the trial opened in 1992, neither of the treatments could have been considered “standard” for this diverse group of patients, although both treatment approaches had their advocates. By the time the trial was published 14 years later, it was generally understood that the dose of radiation used in GOG-122 was inadequate to control gross residual disease, that the volume irradiated was inappropriate for many subsets, and that patients whose only risk factor was positive peritoneal cytology probably did not require adjuvant treatment at all.

Table 30.1

Randomized trials evaluating the roles of adjuvant treatments in patients with endometrial cancer

Author(s) (trial name or country) | Eligibility | Study arms | No. of pts. | LRR rate (%) | DFS rate (%) | OS rate (%) | No. of endometrial cancer-related deaths | Median F/U time, mo | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Trials evaluating the role of lymphadenectomy | |||||||||

Kitchener et al. (MRC ASTEC) [3] | Endometrial carcinoma clinically confined to corpus | Pelvic lymphadenectomy | 704 | – | 73a | 82 | 37 | Median number nodes dissected =12 | |

No lymphadenectomy | 704 | – | 79a | 81 | |||||

Benedetti et al. (Italy) [4] | Endometrioid or adenosquamous carcinoma clinically confined to the corpus | Pelvic lymphadenectomy | 264 | 82 | 86 | 42 (total) | 49 | Median number nodes dissected =12 | |

No lymphadenectomy | 250 | 82 | 90 | ||||||

Trials evaluating the role of adjuvant RT for intermediate-risk disease | |||||||||

Aalders et al. (Norway) [8] | Clinical stage I (FIGO) | Pelvic RT + VBC | 260 | 89 | 28 | >60 | |||

VBC | 277 | 91 | 25 | ||||||

Creutzberg et al. (PORTEC-1) [10] | FIGO I with: G1, >50 % myometrial invasion, G2, any invasion, or G3, <50 % invasion | Pelvic RT | 354 | 4a,c | 81 | 23 | 52 | Lymph node staging not required; no pre-entry pathology review | |

No adjuvant treatment | 361 | 14a,c | 85 | 18 | |||||

Keys et al. (GOG-99) [11] | G2–3 + LVSI + >2/3 invasion | Pelvic RT | 190 | 1.6a | 92d | 19 | 69 | ||

≥50 years old with two of these features | |||||||||

≥70 years old with any of these features | No adjuvant treatment | 202 | 7.4a | 86d | 15 | ||||

Blake et al. (MRC ASTEC/NCIC CTG EN.5) [9] | FIGO (1988) I or IIA with ither G3 (including serous) or >50 % myometrial invasion | Pelvic RT | 452 | 84 | 37 | 58 | Lymph node staging not required; no pre-entry pathology review; VCB given to 53 % in “observation” arm | ||

Observation | 453 | 84 | 41 | ||||||

Nout et al. (PORTEC-2) [12] | FIGO (1988) I or IIA and: | Pelvic RT | 214 | 0.5 | 83 | 80 | 10 | 45 | Lymph node staging not required; no pre-entry pathology review |

G1–2, >60 years old, <50 % invasion or | |||||||||

G3 with <50 % invasion or | |||||||||

IIA, G1–2 or G3, <50 % invasion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |||||||||