The management of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in special populations is challenging. The efficacy and safety data of the currently approved all-oral direct-acting antiviral combinations, including sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, daclatasvir, paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir plus dasabuvir (3D), and ribavirin, is compelling for use in special HCV populations, as has recently been recommended by expert guidelines. The treatment regimens and sustained virological response rates for special populations are nearly similar to those of the general HCV population. Sofosbuvir is not recommended in patients with severe renal impairment, and simeprevir and 3D regimen are not recommended for those with decompensated liver disease.

Key points

- •

The management of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in special populations, including patients with decompensated cirrhosis, liver transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus coinfection, and end-stage renal disease, is challenging.

- •

Interferon-based therapy had reduced efficacy, increased side effects, altered pharmacokinetics, and the potential for drug-drug interactions (DDI), via CYP3A, with boceprevir and telaprevir.

- •

New-generation direct-acting antivirals (DAA) with high potency and no to minimal DDI are preferred, especially as interferon-free regimens. The efficacy and safety data of the currently approved all-oral DAA combinations, containing sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, daclatasvir, paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir plus dasabuvir, and ribavirin, is compelling for use is special HCV populations, as has recently been recommended by the AASLD/IDSA and EASL guidelines.

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a worldwide leading cause of chronic liver disease that affects more than 170 million individuals. Treatment of HCV has been evolving rapidly over the past few years, shifting from a combination of pegylated-interferon (PEG-IFN) plus ribavirin (RBV) to an all-oral combination of direct-acting antivirals (DAA) targeting NS3/4A, NS5A, and NS5B HCV proteins. Experiences have shown that the epidemiology, the natural history, and the response to treatment of HCV vary among certain patient populations, especially in those with decompensated cirrhosis, liver transplantation (LT), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The management of HCV in these populations is challenging, particularly with IFN-based therapy, because of reduced efficacy of treatment, increased treatment-related side effects, altered pharmacokinetics, and the potential for significant drug-drug interactions (DDI) with early-generation protease inhibitors, such as boceprevir, telaprevir, and simeprevir. Accordingly, new-generation DAA with high potency and minimal DDI, especially the IFN-free/RBV-free regimens, are preferred. Recently, the safety and efficacy data of the currently approved all-oral DAA combinations in special HCV populations have been increasingly reported. Although the number of patients is still limited in clinical trials, these data are convincing, which has led to a recommendation for their use in special HCV populations in guidelines published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL).

This review focuses on the DAA-based management of HCV patients with decompensated cirrhosis, post-LT, HIV coinfection, and ESRD, using the currently available regimens in the United States and Europe. In addition, unique clinical features of these HCV populations and the use of IFN-based therapy are briefly reviewed. Important pharmacokinetic and metabolic properties of the currently available DAA are summarized in Table 1 . In addition, at this evolving stage of HCV management, it is suggested that continuous updates on the more recent recommendations for HCV treatment be obtained from the AASLD and the EASL Web sites.

| Drug | Metabolism/Excretion Route | Interaction with CYP and Substrate Transporters | Dosage Adjustment in Patients with Renal Impairment | Dosage Adjustment in Patients with Liver Impairment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS3/4A Protease Inhibitors | ||||

| Telaprevir | Hepatic (CYP3A) | Strong CYP3A inhibitor, moderate P-gp inhibitor | No dose adjustment is required for any degree of RI (clinical data limited) | No dose adjustment is required in compensated cirrhosis; not recommended for CTP class B/C |

| Boceprevir | Hepatic (CYP3A, aldoketo-reductase) | Moderate CYP3A inhibitor, weak P-gp inhibitor | No dose adjustment is required for any degree of RI (clinical data limited) | No dose adjustment is required in compensated cirrhosis; not recommended for CTP class B/C |

| Simeprevir | Hepatic (CYP3A) | Mild CYP1A2 and CYP3A inhibitor, inhibitor of OATP1B1 and MRP2 | No dose adjustment is required for mild-severe RI; no data in ESRD | No dose adjustment is required in compensated cirrhosis; not recommended for CTP class C |

| Paritaprevir (ABT-450)/ritonavir | Hepatic (CYP3A) | Strong CYP3A inhibitor (ritonavir), inhibitor of OATP1B1, substrate of P-gp and BCRP | No dose adjustment is required for mild-moderate RI; no data in severe RI/ESRD | No dose adjustment is required in compensated cirrhosis; not recommended for CTP class C |

| Asunaprevir | Hepatic (CYP3A) | Weak CYP3A4 inducer, moderate CYP2D6 inhibitor, inhibitor of P-gp and OATP1B1 | No dose adjustment is required for any degree of RI (clinical data limited) | No dose adjustment is required in compensated cirrhosis; not recommended for CTP class B/C |

| NS5A Replication Complex Inhibitors | ||||

| Daclatasvir | Hepatic (CYP3A) | Not a CYP3A inducer/inhibitor, moderate inhibitor of P-gp and OATP1B1 | No dose adjustment is required for any degree of RI (clinical data is limited) | No dose adjustment is required in compensated cirrhosis; Not recommended for CTP class C |

| Ledipasvir | Feces (major); hepatic and renal (minor) | Not a CYP inducer/inhibitor, weak inhibitor of P-gp and OATP1B1 | No dose adjustment is required for mild-moderate RI; no data in severe RI/ESRD | No dose adjustment is required for any degree of liver impairment |

| Ombitasvir (ABT-267) | Amide hydrolysis and oxidative metabolism | Not a CYP inducer/inhibitor, substrate of P-gp and BCRP | No dose adjustment is required for mild-moderate RI; no data in severe RI/ESRD | No dose adjustment is required in compensated cirrhosis; not recommended for CTP class C |

| NS5B Nucleotide Polymerase Inhibitors | ||||

| Sofosbuvir | Renal | Not a CYP inducer/inhibitor, substrate of P-gp | No dose adjustment is required for mild-moderate RI; no data in severe RI/ESRD | No dose adjustment is required for any degree of liver impairment |

| NS5B Non-Nucleoside Polymerase Inhibitors | ||||

| Dasabuvir (ABT-333) | Hepatic (CYP2C8 60%, CYP3A4 30%, CYP2D6 10%) | Not a CYP inducer/inhibitor, substrate of P-gp and BCRP | No dose adjustment is required for mild-moderate RI; no data in severe RI/ESRD | No dose adjustment is required in compensated cirrhosis; not recommended for CTP class C |

Treatment of hepatitis C virus in patients with end-stage renal disease

Overview

Epidemiology

The prevalence of HCV infection in patients with ESRD varies among the various geographic areas of the World and dialysis centers, but is clearly higher than in the general population. In a national survey (N = 164,845), the prevalence of anti-HCV positivity among United States dialysis centers was 10.4% in 1985 and 7.8% in 2002 (range 5.5%–9.8%). Although the prevalence and incidence of HCV among ESRD patients on dialysis has declined in the past decades, a recent estimated seroconversion rate of 0.2%–15% per year for dialysis continues to be a cause for concern. Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that all ESRD patients on hemodialysis be screened for anti-HCV at baseline, and subsequently semiannually.

Natural history

HCV infection in patients with ESRD is associated with more rapid liver disease progression, more liver-related mortality, and reduced renal graft and patient survival following kidney transplantation (KT). A meta-analysis on survival in dialysis patients (7 studies; N = 11,589) showed an estimated relative risk for death in anti-HCV–positive patients of 1.34 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.13–1.59), with liver-related complications contributing to poorer outcomes.

It should also be noted that serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in patients with ESRD are lower than in the general population, and there is a weak correlation between ALT levels and liver disease severity in this population. Liver biopsy or noninvasive assessment of the stage of liver fibrosis is recommended in all HCV-positive KT candidates. Patients with established cirrhosis and portal hypertension often have poor outcomes after KT, particularly if they failed (or are not suitable for) HCV treatment, so that an isolated KT may be contraindicated in this setting, and consideration should be given for a combined liver and KT.

Management

Interferon-based therapy

The pharmacokinetics of IFN and RBV are altered in patients with ESRD. In patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance, CrCl <30 mL/min), the maximum plasma concentration and the area under the curve (AUC) of PEG-IFN α2a and α2b are increased by approximately 90% and the half-life is increased by approximately 40%. RBV has an extensive volume of distribution and is primarily excreted renally, so that its AUC is increased by more than 2-fold in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment. Hemodialysis has only a minimal effect on PEG-IFN and RBV clearance. Several studies and meta-analyses have reported that IFN or PEG-IFN monotherapy is effective for HCV patients with ESRD, with overall sustained virological response (SVR) rates of 33% to 41% and withdrawal rates of 17% to 30%. Later, a randomized trial of 205 HCV patients with ESRD revealed that addition of low-dose RBV to PEG-IFN treatment was associated with higher rates of SVR (64% vs 33%, P <.001) and anemia (hemoglobin <8.5 g/dL) (72% vs 6%, P <.001), with comparable discontinuation rates (7% vs 4%, P not significant). With dose adjustment and careful monitoring, treatment with PEG-IFN plus RBV in HCV patients with ESRD can be associated with SVR rates nearly comparable with those with normal renal function. Of note, in patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD on dialysis, the recommended starting doses are 135 μg/wk for PEG-IFN α2a, 1 μg/kg/wk (or 50% reduction) for PEG-IFN α2b, and 200 mg/d for RBV. However, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Guideline 2008 does not recommend adding RBV in patients with stage 5 chronic renal disease (CrCl <15 mL/min or dialysis).

It should also be noted that IFN-based treatment is often ineffective in HCV-positive KT recipients and may be associated with a risk of graft rejection (15%–100%). Therefore, IFN-based therapy should only be initiated in KT recipients under specific clinical situations, such as fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis (FCH) or severe de novo glomerulonephritis, when DAA are unavailable and the risk of not treating HCV infection outweighs the risk of graft loss.

All-oral direct-acting antiviral therapy

Based on the available data, the AASLD/IDSA guidance advised that no dose reduction is needed when using sofosbuvir in HCV patients with mild to moderate renal impairment (CrCl ≥30 mL/min). However, until more data becomes available sofosbuvir is not recommended in patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD (CrCl <30 mL/min) or those who require dialysis. For DAA with primarily hepatic metabolism (eg, boceprevir, simeprevir, daclatasvir, and paritaprevir), no dosage adjustment is required for patients with mild to moderate to severe renal impairment. However, the clinical safety and efficacy of these agents in patients with ESRD, including those requiring dialysis, are still limited. In a preliminary report of the RUBY-1 study, the 3D regimen (without RBV for genotype 1b and with RBV 200 mg/d for genotype 1a) was associated with an SVR 4 (ie, SVR after 4 weeks) rate of 100% in HCV genotype 1 patients with severe renal impairment or ESRD (n = 10). The 3D regimen was well tolerated, and there was 1 case of anemia (hemoglobin <8 g/dL) without the need for blood transfusion or treatment discontinuation among 17 patients in this ongoing trial. A phase II clinical study (NCT01958281) is currently under way to assess optimal dosing of sofosbuvir plus RBV for HCV patients with severe renal impairment. Grazoprevir (an NS3/4A inhibitor, formerly MK-5172) and elbasvir (a NS5A inhibitor, formerly MK-8742) are both less than 1% renally excreted, and no dose adjustment is needed for ESRD. A preliminary report (N = 111) of a phase II/III C-SURFER study demonstrated that once-daily grazoprevir plus elbasvir for 12 weeks was well tolerated and highly effective (SVR 12 99%) for the treatment of HCV genotype 1 among patients with CrCl less than 30 mL/min (75% on dialysis).

Treatment of hepatitis C virus in patients with decompensated cirrhosis

Overview

Chronic HCV infection is generally a slowly progressive disease characterized by persistent hepatic inflammation, leading to the development of cirrhosis in approximately 10% to 40% of patients over 20 to 30 years of infection. Once cirrhosis has developed, the disease progression remains unpredictable with the overall 1% to 5% annual risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and 3% to 6% annual risk of hepatic decompensation. Following an episode of decompensation, the risk of death in the following year is between 15% and 20%, and LT generally remains the only life-saving option.

Management

Treatment of HCV is strongly recommended for patients with advanced fibrosis and compensated cirrhosis, as an SVR in this high-risk group is associated with a significant decrease in the incidence of clinical decompensation and HCC, although the risk is not eliminated. However, the SVR rates are generally lower with IFN-based therapies, and side effects occur more commonly in patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in comparison with patients with mild to moderate fibrosis. Furthermore, successful viral eradication in patients with decompensated cirrhosis independently reduces portal hypertension, decreases the likelihood of clinical decompensation, and improves survival, which may then facilitate, delay, or, in a small proportion of patients, avoid LT, and prevent HCV recurrence following LT. Of note, in patients who achieved SVR before LT, the incidence of HCV recurrence after LT is low (0%–20%). In a meta-analysis that included 2649 HCV patients with advanced liver disease, SVR was associated with a reduction in the overall risk of developing HCC from 17.8% to 4.2%, with a reduction in incidence from 3.3% per person-year to 1.05% (95% CI 0.7%–1.5%) per person-year.

Interferon-based therapy

In the past, the outcome of IFN-based therapy in patients with decompensated cirrhosis had been disappointing because of low efficacy (SVR 7%–30% for genotype 1, and 44%–57% for genotypes 2, 3) and high rates of treatment-related side effects (led to dose reduction in 40%–70% and treatment discontinuation in 13%–40%). A French cohort (CUPIC Study Group) of HCV genotype 1 with cirrhosis treated with boceprevir-based or telaprevir-based triple therapy (N = 674) reported a high incidence of serious adverse events, including death, related to a platelet count of less than 100,000/mm 3 and/or albumin less than 3.5 g/dL at baseline. In addition, the real-world experience HCV-TARGET study (N = 2084; all genotype 1, 38% with cirrhosis) revealed that triple therapy was associated with high rate of adverse events (>90%), particularly anemia (66%), and involved frequent treatment modifications. Five deaths occurred in this study and the overall SVR rate was 52%. Therefore, these triple-therapy regimens have no role in patients with decompensated liver disease.

All-oral direct-acting antiviral therapy

The pharmacokinetics of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir do not appear to change significantly in patients with moderate or severe liver impairment. A fixed-dose combination of paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir plus dasabuvir and RBV is safe in patients with compensated cirrhosis, but should not be used in decompensated patients. Similarly, simpeprevir is not recommended in Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) class B and C cirrhosis. The AASLD/IDSA guideline recommends that patients with decompensated cirrhosis can be treated with all-oral DAA regimens containing sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, and RBV, according to the HCV genotype ( Table 2 ). In addition, the EASL panel also recommends sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir and weight-based RBV as an option for patients with decompensated cirrhosis awaiting LT. These recommended all-oral combination regimens are generally associated with SVR rates nearly similar to those of patients without decompensated cirrhosis. Of note, antiviral therapy should be started at least 3 months before anticipated surgery with a goal of undetectable HCV-RNA for at least 30 days. The phase III ALLY-1 study evaluated a 12-week course of daclatasvir 60 mg daily, sofosbuvir 400 mg daily, and RBV (initially 600 mg/d, adjusted to 1000 mg/d based on hemoglobin levels) in patients with HCV genotypes 1 to 6 (about 70% were genotype 1) with advanced cirrhosis (n = 60) or post-LT HCV recurrence (n = 53). In an advanced cirrhosis cohort, SVR 12 was achieved in 92%, 94%, and 56% of patients with CTP-A (n = 12), CTP-B (n = 32), and CTP-C (n = 16), respectively. Most patients improved their Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores following treatment, although some patients continued to show further increases in MELD score. In the post-LT cohort, SVR 12 was achieved in 92% of patients without the need for dose modification of immunosuppressive agents. Among patients with genotype 3 (n = 17), the SVR 12 rate was 83% in advanced cirrhosis and 91% in the post-LT cohort.

| AASLD/IDSA | EASL | |

|---|---|---|

| HCV genotype 1 | SOF-LDV + RBV (initial dose of 600 mg, increased as tolerated) for 12 wk (consider 24 wk for prior SOF failure) SOF-LDV for 24 wk (if anemia or RBV intolerance) | SOF-LDV + RBV (initial dose of 600 mg, increased as tolerated) for 12 wk SOF + DCV + RBV for 12 wk |

| HCV genotype 2 | SOF + RBV for up to 48 wk | SOF + DCV + RBV for 12 wk SOF + RBV for 12 wk |

| HCV genotype 3 | SOF + RBV for up to 48 wk | SOF + DCV + RBV for 12 wk |

| HCV genotype 4 | SOF-LDV + RBV for 12 wk (consider 24 wk for prior SOF failure) SOF-LDV for 24 wk (if anemia or RBV intolerance) | SOF-LDV + RBV for 12 wk SOF + DCV + RBV for 12 wk |

In the SOLAR-1 study, 108 treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients with HCV genotypes 1 and 4 who had decompensated cirrhosis (59 had CTP-B and 49 had CTP-C) were randomized to receive daily fixed-dose combination sofosbuvir/ledipasvir and RBV (initial dose 600 mg, increased as tolerated) for 12 or 24 weeks. SVR was achieved in 87% and 89% of patients treated for 12 weeks and 24 weeks, respectively. Most patients improved their CTP and MELD scores following treatment, although some patients continued to show further increases in MELD score, demonstrating that there may be a point of no return for recovery of liver function in those who present with late liver disease. There were 5 deaths during the study, none of which were attributed to antiviral treatment. Grade 3 or 4 side effects developed more commonly in the 24-week arm (34%) than in the 12-week arm (15%). In a preliminarily report of the SOLAR-2 study, a fixed-dose combination sofosbuvir/ledipasvir and RBV for 12 to 24 weeks was associated with SVR 12 rates of 87% to 89% and 72% to 85% in HCV genotype 1 patients with cirrhosis CTP-B (n = 46) and CTP-C (n = 38), respectively. The administration of sofosbuvir plus RBV before LT has been shown to prevent post-LT HCV recurrence in an open-label study of 61 patients with CTP-A and HCV of any genotype who were on wait lists for LT for hepatocellular carcinoma. In addition, a report from the NHS England Early Access Program has confirmed the efficacy of a 12-week course of sofosbuvir plus a NS5A inhibitor, either ledipasvir or daclatasvir, with or without RBV for HCV genotype 1 or 3 in more than 400 patients with decompensated cirrhosis. A preliminary result of the phase II/III C-SALT study revealed that grazoprevir plus elbasvir for 12 weeks was well tolerated and highly effective (SVR 4 93%) in 30 patients with CTP-B and HCV genotype 1. Of note, from all these studies data in patients with more advanced liver disease (CTP score >12 or MELD score >20) are limited. Thus the decision to treat HCV in patients with decompensated cirrhosis to maximize survival should be individualized, together with a consideration of the expected waiting time to LT. It is debatable whether the decompensated patients with MELD greater than 15 should be treated before LT with aim to cure or to prevent post-LT recurrence, or that such patients should be monitored until LT and treatment initiated at the time of established recurrence of HCV.

Treatment of hepatitis C virus in liver transplant recipients

Overview

Epidemiology

HCV infection is the most common indication for LT in the United States, Japan, and many countries in Europe. Based on the United States database (the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network), among 126,862 new primary registrants for LT between 1995 and 2010, 41% had HCV. Although effective therapies are currently available and the prevalence of HCV has already peaked and is now decreasing, it is predicted that the number of cases of advanced liver disease, HCC, and liver-related deaths will continue to increase through 2030 globally. In addition, there is a trend toward increasing age and occurrence of HCC in HCV-positive LT candidates, which will be a further challenging problem to the transplant community.

Natural history

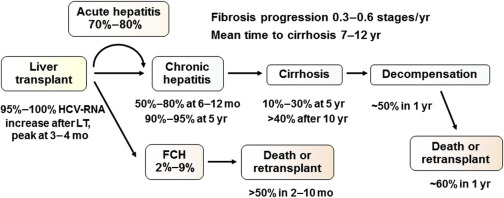

Liver transplantation in HCV patients is associated with suboptimal graft survival, which is attributable to universal recurrence of HCV in the graft. The natural course of HCV is accelerated in LT recipients, with more than 40% progressing to cirrhosis within 10 years and approximately 50% developing liver failure shortly thereafter. ( Fig. 1 ) An analysis of the UNOS database (N = 11,036) before the era of effective antiviral therapy (1992–1998) revealed that LT in HCV-positive recipients was associated with an increased rate of death (hazard ratio [HR] 1.23; 95% CI 1.12–1.35) and allograft failure (HR 1.30; 95% CI: 1.21–1.39), compared with LT for other indications.

A subset of patients (2%–9%) may develop post-LT FCH, which is characterized by persistent cholestasis of at least 4 weeks’ duration, high HCV-RNA, hepatocyte ballooning, rapid progression to graft failure, and, in the absence of biliary and hepatic artery complications, sepsis and drug-induced cholestasis. This complication is often resistant to antiviral therapy, and leads to death in more than 50% of patients.

The benefit of immunosuppressive strategy on the natural history HCV recurrence has not been well elucidated, although there has been evidence to suggest a neutral or small beneficial effect of cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and sirolimus.

Management

In the IFN era, the recommended standard of care for LT recipients was treatment of confirmed significant or progressive recurrent HCV disease, based either on persistent, unexplained, elevated ALT levels or on histologically confirmed fibrosis, once rejection, biliary obstruction, vascular complication, and other causes had been excluded. This recommendation was based on the limited efficacy and increased treatment-related side effects of IFN-based therapy in immunosuppressed patients. When new DAA become widely available, IFN-based therapies will generally no longer be recommended, and all patients with post-LT recurrence of HCV will be considered for therapy. New-generation DAA with higher potency and no/minimal DDI are preferred, ideally as IFN-free/RBV-free regimens. The optimal time period to initiate such treatment is before the development of significant fibrosis.

Interferon-based therapy

Treatment with PEG-IFN/RBV has been associated with SVR rates of 24% to 40% in LT recipients, but adverse effects are common (two-thirds of patients required dose reductions and one-fourth discontinued treatment early). Addition of boceprevir or telaprevir to a PEG-IFN/RBV regimen improves SVR rates but also increases treatment-related side effects, and has a DDI issue with calcineurin inhibitors whereby the immunosuppressive regimens need to be closely monitored and preemptively adjusted during the treatment period.

All-oral direct-acting antiviral therapy

The AASLD/IDSA and EASL guidelines recommend that patients who develop recurrent HCV post-LT, including those with compensated cirrhosis, can be treated with all-oral DAA regimens, according to genotype. ( Table 3 ) Tacrolimus or cyclosporine dose adjustments are not needed when coadministered with regimens that include sofosbuvir, ledipasvir, daclatasvir, and RBV. However, careful monitoring is recommended because of the limited safety data in this group of patients ( Table 4 ). In the SOLAR-1 study, 223 LT recipients who had recurrent HCV with genotype 1 or 4 (111 with METAVIR stage F0–F3, 51 with CTP-A, and 61 with CTP-B/C) were randomized to receive a daily fixed-dose combination sofosbuvir/ledipasvir and RBV (weight-based dose for noncirrhotics and CTP-A cirrhosis; and initial dose of 600 mg, increased as tolerated for CTP-B/C), for either 12 or 24 weeks. Overall, SVR was attained in 96% of patients with F0 to F3 and 96% of those with compensated cirrhosis, in both treatment arms. Efficacy of treatment was lower in patients with decompensated cirrhosis (85% in CTP-B and 60% in CTP-C), without the increase in SVR observed in patients treated for 24 weeks. To date, there have been fairly limited data for LT recipients with recurrent HCV genotype 3; however, a 24-week course of sofosbuvir plus RBV was effective, as in non-LT settings. In a preliminary report of SOLAR-2, a fixed-dose combination sofosbuvir/ledipasvir and RBV for 12 to 24 weeks was associated with SVR 4 rates of 94% to 100%, 92% to 97%, 100%, and 50% to 100% in LT recipients who had recurrent HCV with genotype 1 or 4 with METAVIR F0 to F3 (n = 100), CTP-A (n = 67), CTP-B (n = 44), and CTP-C (n = 9), respectively.