Transvaginal

G. Willy Davila

Introduction

Rectocele repair represents one of the most commonly performed gynecologic pelvic reconstructive procedures. Both gynecologists and colorectal surgeons treat rectoceles on a frequent basis by itself or in conjunction with other reconstructive procedures. Dysfunction of the posterior compartment may be very differently managed by different specialists as there is a lack of consensus about indications, surgical techniques, and outcome assessment.

The restoration of normal anatomy to the posterior vaginal wall is referred to as a posterior repair or colporrhaphy. Although frequently used interchangeably with the term “rectocele repair,” the two operations may have vastly different treatment goals. While rectocele repair focuses on repairing a herniation of the anterior rectal wall into the vaginal canal due to a weakness in the rectovaginal septum, a posterior colporrhaphy is designed to correct a rectal bulge, as well as normalize vaginal caliber by restoring structural integrity to the posterior vaginal wall and introitus.

This chapter will cover various aspects of the gynecologic approach to rectocele repair, including symptoms, anatomy, physical examination, indications for repair, surgical techniques, and treatment outcomes.

Symptoms

Posterior vaginal support defects can occur with or without symptoms. Posterior wall weakness typically entails pelvic and perineal pressure, a vaginal bulge, associated lower back pain, and/or defecatory dysfunction including a sense of incomplete emptying, tenesmus, need to splint, or use digitalization for defecation.

Defecatory Function

Weber et al. described defecatory dysfunction in association with pelvic organ prolapse > stage I. In this study, 92% reported bowel movements at least every other day, 63% needed to strain, 29% required digitation of the rectum during bowel movement, and

14% reported fecal incontinence. Many women need to digitally reduce or splint the posterior vaginal bulge or the perineum in order to initiate or complete a bowel movement. Accumulation of stool within the rectocele reservoir leads to increasing degrees of perineal pressure and obstructive defecation. In the absence of digital reduction, women will note incomplete emptying, which leads to a high degree of frustration. A vicious cycle of increasing pelvic pressure, need for stronger Valsalva efforts, enlargement of the rectocele bulge, and increasing perineal pressure ensues. Rectal digitation is not commonly self-reported by patients with a symptomatic rectocele unless asked by their physicians.

14% reported fecal incontinence. Many women need to digitally reduce or splint the posterior vaginal bulge or the perineum in order to initiate or complete a bowel movement. Accumulation of stool within the rectocele reservoir leads to increasing degrees of perineal pressure and obstructive defecation. In the absence of digital reduction, women will note incomplete emptying, which leads to a high degree of frustration. A vicious cycle of increasing pelvic pressure, need for stronger Valsalva efforts, enlargement of the rectocele bulge, and increasing perineal pressure ensues. Rectal digitation is not commonly self-reported by patients with a symptomatic rectocele unless asked by their physicians.

Patients very commonly have associated complaints of constipation. The symptom of constipation is not clearly understood by all gynecologists. Its vague nature, coupled with a poor understanding of the complexity of colonic function, frequently results in an incomplete evaluation of the symptom of constipation by the gynecologist. Unfortunately, this may result in surgical treatment of abnormal bowel function via a rectocele repair when conservative therapy for constipation may have been satisfactory. The persistence of abnormal defecation symptoms postoperatively may be responsible for the high rectocele recurrence rate.

Sexual Dysfunction

This disorder has a significant prevalence in pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Prolapse in general has been associated with sexual complaints in several studies. Common sexual symptoms about female sexual dysfunction in relation with pelvic organ prolapse include dyspareunia, decreased sexual desire, and anorgasmia. An enlarging rectocele will widen the levator hiatus and increase vaginal caliber. In addition, women with increasing degrees of prolapse have progressively larger genital hiatuses (4), which may lead to sexual difficulties including symptoms of vaginal looseness and decreased sensation during intercourse. Whether this is due to the enlargement of the vaginal introitus and levator hiatus or coexistent damage to the pudendal nerve supply to the pelvic floor musculature is unclear. Some theoretical explanations for sexual dysfunction due to posterior wall pelvic organ prolapse can be due to the loss or damage to pudendal terminal nerve endings, caused either by loss of support of the perineum and distal vagina, by surgical dissection, or by a vasculogenic factor (diminished pelvic blood flow) causing hypoxia, mucosal dryness, and dyspareunia.

Rectocele, Enterocele, and Perineal Descent

The vaginal epithelium can provide clear signs about the location of the rectovaginal fascia tears because the rugation pattern is frequently lost above the defect. Rectoceles can be caused by transverse, lateral, central, distal, or superior fascial tears (2). In general, enteroceles and most rectoceles are caused by superior tears at the cervical or vaginal cuff level, with very thin, unrugated epithelium noted overlying the defect. Denervation of the pelvic diaphragm results in opening of the genital hiatus and separation of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls, loss of muscular tone, and laxity in the rectovaginal fascia. As such, pressure applied to the anterior and posterior vaginal walls must be counteracted upon by the connective tissue alone. The connective tissue response to constant pressure is attenuation or tearing of the rectovaginal fascia. A large enterocele or rectocele may extend beyond the hymeneal ring. Once exteriorized, the patient is at risk for vaginal mucosal erosion and ulceration. Normally, the perineum should be located at the level of the ischial tuberosities or within 2 cm of this landmark. A perineum found below this level either at rest or with straining represents perineal descent and is usually caused by a detachment of the rectovaginal fascia from the vaginal apex/uterus or less commonly from the perineal body. It translates to a widening of the genital hiatus and perineal body and flattening of the intergluteal sulcus. Excessive perineal descent can be related to as little as a 20% elongation of the pudendal nerve fibers.

Anatomy

The anatomy of the posterior vaginal wall cannot be clearly conceptualized apart from the anatomical support of the rest of the vagina. Vaginal support arises from several interactions between pelvic musculature and connective tissue.

Rectoceles result from defects in the integrity of the posterior vaginal wall and rectovaginal septum and subsequent herniation of the posterior vaginal wall and anterior rectal wall into the vaginal lumen through these defects.

The normal posterior vagina is lined by squamous epithelium that overlies the lamina propria, a layer of loose connective tissue. A fibromuscular layer of tissue composed of smooth muscle, collagen, and elastin underlies this lamina propria and is referred to as the rectovaginal fascia. This is an extension of the endopelvic fascia that surrounds and supports the pelvic organs and contains blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves that supply and innervate the pelvic organs.

The layer of tissue between the vagina and the rectum, or rectovaginal fascia, was felt to be analogous to the rectovesical septum in males and became known as Denonvilliers’ fascia or the rectovaginal septum in the female. Others described the rectovaginal septum as a support mechanism of the pelvic organs, and they were successful in identifying this layer during surgical and autopsy dissections (13,19,21). It is unclear whether this fascial layer extends from the vaginal cuff to the perineum or is only present along the distal vaginal wall from the levator reflection to perineum.

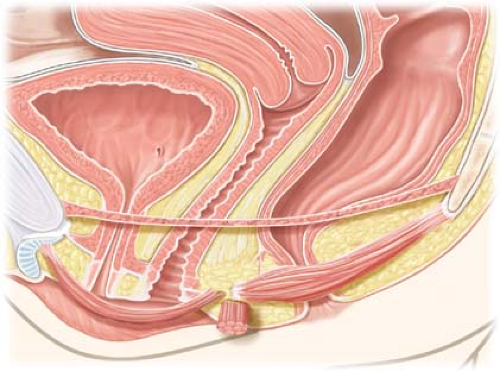

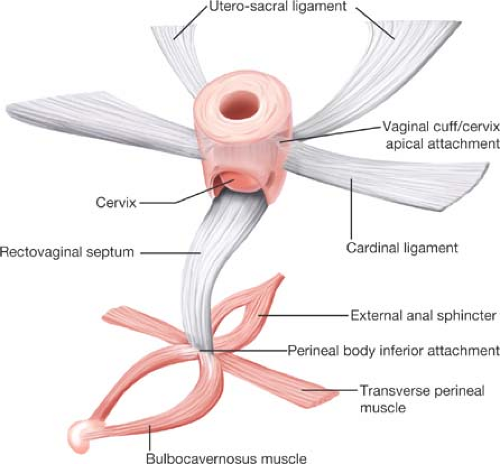

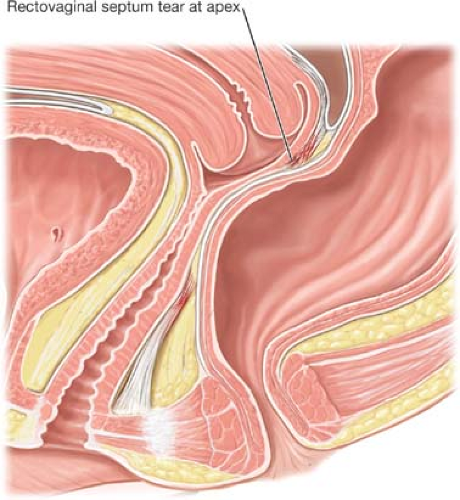

The normal vagina is stabilized and supported on three levels. Superiorly, the vaginal apical endopelvic fascia is attached to the cardinal–uterosacral ligament complex. Laterally, the endopelvic fascia is connected to the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis, with the lateral posterior vagina attaching to the fascia overlying the levator ani muscles. Inferiorly, the lower posterior vagina connects to the perineal body, comprised of the anterior external anal sphincter, transverse perineum, and bulbous cavernosus muscles. The cervix (or vaginal cuff in the women following hysterectomized woman) is considered to be the superior attachment site or “superior tendon,” and the perineal body the inferior attachment site or “inferior tendon.” The endopelvic fascia extends between these two sites comprising the rectovaginal septum (Fig. 22.1). A rectocele results from a stretching or actual separation or tear of the rectovaginal fascia, leading to a bulging of the posterior vaginal wall noted on examination during a Valsalva maneuver. Trauma from vaginal childbirth commonly leads to transverse defects above the usual location of the connection to the perineal body (Fig. 22.2). In addition, patients may present with lateral, midline, or high transverse fascial defects. Separation of the rectovaginal septum fascia from the vaginal cuff results in the development of an enterocele as a hernia sac without fascial lining and filled with intraperitoneal contents (Fig. 22.2).

Vaginal muscular support is provided by the interrelation among the pelvic diaphragm, the levator ani muscles (puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and ileococcygeus), and the coccygeus muscles. The levator musculature extends from the pubic bone to the coccyx and provides support for the change in vaginal axis from vertical to horizontal along the mid-vagina creating a U-shaped sling. A rectocele typically develops at, or below, the levator plate, along the vertical vagina, weakening the fascial condensation of the attachments of the perineal musculature (Fig. 22.3).

Physical Examination

Pelvic examination allows the surgeon to define the grade of prolapse and determine the integrity of the connective tissue and muscular support of the posterior vaginal wall. The typical finding in a woman with a symptomatic rectocele is a lower posterior

vaginal wall bulge noted on physical examination in a dorsal lithotomy position. It may superiorly extend to weaken the support of the upper, posterior vaginal wall, leading to an enterocele, or to the vaginal apex, leading to vaginal vault prolapse. In an isolated rectocele, the bulge extends from the edge of the levator plate to the perineal body. As the rectocele enlarges, the perineal body may further distend and lose its bulk, leading to an evident perineocele; enteroceles and rectoceles frequently coexist. The physical

examination should include not only a vaginal examination but must also include a rectal examination, as the perineocele may not be evident on vaginal examination. At times, it can be identified only upon digital rectal examination where an absence of fibromuscular tissue in the perineal body anterior to the rectum is confirmed.

vaginal wall bulge noted on physical examination in a dorsal lithotomy position. It may superiorly extend to weaken the support of the upper, posterior vaginal wall, leading to an enterocele, or to the vaginal apex, leading to vaginal vault prolapse. In an isolated rectocele, the bulge extends from the edge of the levator plate to the perineal body. As the rectocele enlarges, the perineal body may further distend and lose its bulk, leading to an evident perineocele; enteroceles and rectoceles frequently coexist. The physical

examination should include not only a vaginal examination but must also include a rectal examination, as the perineocele may not be evident on vaginal examination. At times, it can be identified only upon digital rectal examination where an absence of fibromuscular tissue in the perineal body anterior to the rectum is confirmed.

Figure 22.1 Diagrammatic representation of the rectovaginal septum including its attachment from vaginal apex to perineal body. |

Figure 22.2 Fascial tears of the rectovaginal (RV) septum can occur superiorly or inferiorly at sites of attachment to a central tendon. |