Minimal to mild nonspecific chronic portal inflammation is common in potential donor liver biopsies, but if the portal inflammation is diffuse or more than mild, the donor may have an undiagnosed chronic hepatitis. Necrosis, if present, is typically in the zone 3 hepatocytes. Necrotic hepatocytes may still retain their normal size and sometimes even their nuclei, but the hepatocyte cytoplasm becomes distinctly oncocytic.

The frozen section H&E stain may not pick up mild portal fibrosis but can identify more significant levels of fibrosis including bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis. A trichrome stain should be performed on the permanent section to establish the baseline fibrosis.

Iron stains are also commonly performed on permanent sections. There is relatively little data on the clinical relevance of iron positivity in donor livers. In one study, iron was found in 49 out of 284 (17%) donor biopsies and was occasionally at moderate levels but overall did not impact survival outcomes.4 However, one of the few other published studies found that increased iron at baseline increased the risk for subsequent fibrosis progression in women transplanted for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV).5 Inadvertent transplantation of individuals with marked iron overload has also been reported,6 but the number of cases is too small to draw strong conclusions on the posttransplant course. Likewise, the full range of outcomes in cases of inadvertent transplantation of livers with C282Y HFE mutations has not been fully defined. Nonetheless, case reports have demonstrated that iron can accumulate rapidly in homozygotes.7

PRESERVATION CHANGES IN THE ALLOGRAFT

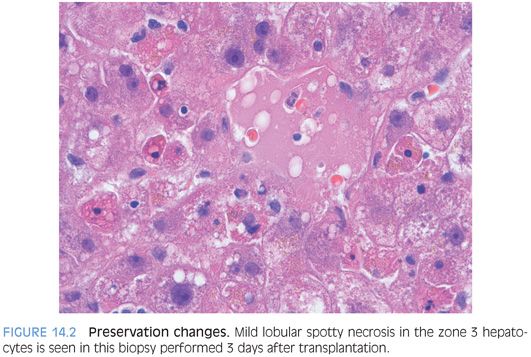

Preservation changes can vary considerably in severity but typically include increased hepatocyte apoptosis (Fig. 14.2, eFig. 14.1), minimal to focally mild portal and lobular lymphocytic inflammation, and scattered lobular Kupffer cell aggregates. Scattered ballooned hepatocytes may be present along with mild cholestasis. Overall, the changes tend to be more pronounced in zone 3 hepatocytes. Steatosis can be present and will reflect the amount of fat in the biopsy at the time of donation.

In rare cases with marked steatosis, dying hepatocytes can release fat globules that stay in the hepatic cords and mimic dilated sinusoids.8,9 In cases with more severe liver necrosis, the fat droplets can enter into the sinusoids causing true sinusoidal obstruction8 and even migrate to the lungs causing pulmonary fat emboli.9 However, other cases appear to self-clear, and the overall prognosis depends on the amount of liver necrosis.8 The term pseudopeliotic steatosis has been proposed for this finding.9

ACUTE CELLULAR REJECTION

Definition

Acute cellular rejection is an immune-mediated, lymphocyte-based, inflammatory response to the allograft liver by the recipient’s immune system.

Clinical Findings

The clinical findings are generally mild and nonspecific, and many mild acute cellular rejections may have no clinical findings. More severe cases can present with upper quadrant pain. In some cases, rejection can be associated with increased serum white blood cell counts and/or eosinophilia. Most episodes of acute cellular rejection occur within the first several months following transplantation, but they can occur as late as many years after transplantation. At most centers, acute cellular rejection is rarely seen in the first few weeks after transplantation. However, some immune suppression sparing protocols can have a higher frequency of acute cellular rejection, including frequent rejection seen on day 7 biopsies. Clinical triggers for rejection can include changes in immunosuppressive medications, or anything that upregulates the immune system, such as an ascending cholangitis. Other risk factors include older allograft donor age, younger recipient age, and underlying autoimmune conditions such as primary sclerosing cholangitis or autoimmune hepatitis.

Laboratory Findings

In most cases of rejections, there will be a relatively abrupt increase of liver enzymes above their baseline. The alkaline phosphatase levels will generally increase more than the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), but the AST and ALT typically increase also.

Histologic Findings

The Banff group has played an enormous role in defining and standardizing the histologic diagnosis of acute cellular rejection. Their publications are excellent and are an important tool for surgical pathologists to stay current on important issues in transplant pathology. For example, their seminal 1997 paper on acute cellular rejection laid the foundation for our current and ongoing approach to the histologic diagnosis of rejection.10

Acute cellular rejection is fundamentally an inflammatory process, and the key findings include portal inflammation, bile duct injury, and endothelialitis. The Banff classification requires at least two out of three of these findings to be present. In episodes of rejection that occur within the first months to year following transplant, essentially all will have portal lymphocytic inflammation and the vast majority will have duct injury. Episodes of rejection that occur later in the clinical course can have a similar pattern, but there also are several additional patterns that can be seen, which have little or no duct injury. Endothelialitis may be absent, especially in milder episodes of late-onset acute cellular rejection.

ACUTE CELLULAR REJECTION AND PORTAL INFLAMMATION. Portal inflammation is predominately lymphocytic but often includes a mild prominence in eosinophils (eFig. 14.2) as well as occasional plasma cells. The lymphocytes can be larger with somewhat more irregular nuclei, a subtle finding that is referred to as being “activated.” The inflammation is largely T cells and can range from mild to marked, with most cases on the milder end. Some degree of portal inflammation is present in essentially all cases of acute cellular rejection. In addition, acute cellular rejection will also have some component of either or both of bile duct injury and endothelialitis.

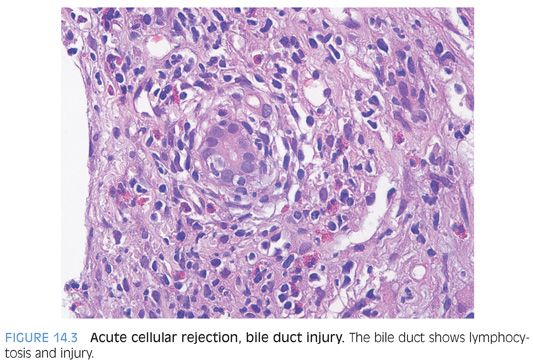

BILE DUCT INJURY. The best evidence for bile duct injury includes bile duct lymphocytosis and apoptosis (Fig. 14.3, eFigs. 14.3 and 14.4). More subtle findings include nuclear enlargement and “reactive changes.” Overemphasis on the subtle findings can often lead to overdiagnosis of rejection because the milder findings are also very nonspecific. In rare cases, the rejection can also affect the canals of Hering (eFigs. 14.5 and 14.6).

Bile duct lymphocytosis can also be seen in cases of recurrent hepatitis C, but bile duct injury is typically minimal, often equivocal, and almost always focal. Furthermore, it is usually associated with moderate or marked portal chronic inflammation. In contrast, mild acute cellular rejection often has only mild portal lymphocytic inflammation but clear and unequivocal duct injury. Furthermore, the duct injury in acute cellular rejection is more than focal in almost all cases: It is often patchy but is almost never limited to a single portal tract. These observations can provide assistance in cases where you are struggling between rejection versus recurrent hepatitis C.

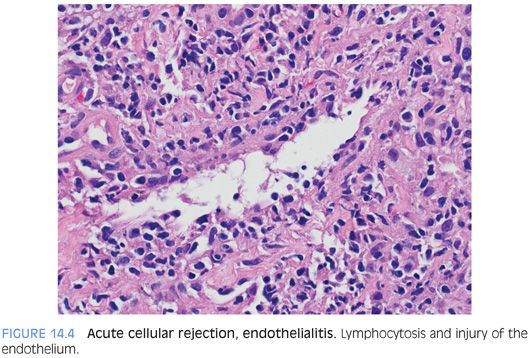

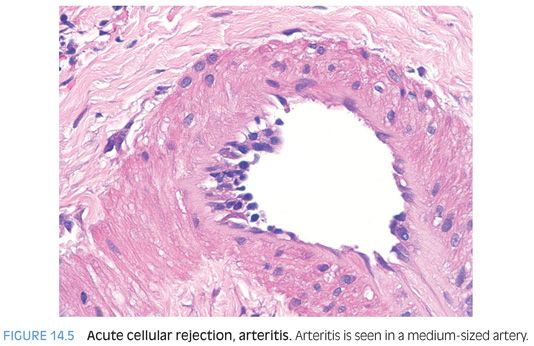

ENDOTHELIALITIS. Endothelialitis is diagnosed by identifying either portal veins or central veins that have lymphocytes adjacent to the endothelial cells or within the lumen and adherent to the endothelial cells (Fig. 14.4). The endothelial cells should also appear “different” than those in veins that are not affected. The terms reactive or injured are often used to describe these affected endothelial cells. They can appear larger and have more hyperchromatic nuclei and may be lifted off of their basement membrane (eFig. 14.7). Endothelialitis can be easy to overcall; there should be clear endothelial reactive changes or injury to make the diagnosis (see eFigs. 14.8 to 14.11 for additional images). Cellular rejection can also involve the hepatic arteries (Fig. 14.5), but this finding is uncommon.

Pathologists are often tempted into overdiagnosing endothelialitis because inflammatory cells are frequently near the vessels in the portal tracts, regardless of whether there is rejection. In addition, mild nonspecific reactive endothelial changes are common. To be diagnostically useful, the endothelial injury should not be equivocal. If you find a focus of equivocal endothelialitis, you can often take guidance from the rest of the biopsy—if there are no other foci of endothelialitis, or if the other features of rejection are not well developed elsewhere in the biopsy, then the equivocal focus is probably nonspecific.

Immunostain Findings

Immunostains are not necessary nor specifically useful to make a diagnosis of acute cellular rejection. In cases where the differential includes a lymphoproliferative disorder, immunophenotyping the lymphocytes can be helpful because rejection has predominantly T cell infiltrates, whereas most Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–related lymphoproliferative disorders are B cell–related.

Differential

The differential is typically between acute cellular rejection and recurrent disease. At the clinical level, there is significant overlap between recurrent liver disease and acute cellular rejection, which limits the usage of clinical and laboratory findings alone to guide therapy, and biopsies can be very helpful in patient management. However, interpreting liver biopsies in isolation, without clinical and laboratory information, likewise limits the value of the liver biopsy. Thus, make sure to have all the information that you can when you make your diagnosis.

The most commonly encountered differential is that of recurrent hepatitis C versus acute cellular rejection. The patterns of injury seen in recurrent hepatitis C vary depending on the time posttransplantation. These findings are discussed in more detail in the section on recurrent hepatitis C. It is often noted that there is histologic overlap between recurrent hepatitis C and rejection. For example, it is well known that hepatitis C in nontransplanted individuals can have bile duct injury and endothelialitis. Although these points are true, it should not obscure a larger truth; in general, there are sufficient dissimilarities between the injury patterns in recurrent hepatitis C and rejection that a diagnosis of one or the other can be confidently made in most cases. Part of the challenge is simply that of experience—it can be hard to feel confident if you do not see very many liver transplant biopsies. In these cases, judicious use of consultant pathologists can be very helpful in both specific case management and in refining your own skills in this area. One of the common diagnostic pitfalls is to focus on single criterion rather than the overall pattern. As one example, focal minimal duct injury in a biopsy that shows otherwise typical changes of hepatitis C should be called hepatitis C and not rejection.

The differential for acute cellular rejection can also include a drug reaction. An allergic-type reaction can sometimes manifest with significant graft eosinophilia. In most cases, however, a potential drug reaction will be idiosyncratic and will not have eosinophilia and you will have to rely on other findings. The most useful guideline is to think of drug reactions when the histologic patterns are unusual for rejection or when the clinical setting is a poor fit. As one example, a biopsy that shows substantial and aggressive duct injury but has only mild portal chronic inflammation with no endothelialitis is somewhat unusual and should prompt a differential of a drug reaction. As a second example, in a patient transplanted for chronic hepatitis C, a marked lobular cholestasis with only minimal portal chronic inflammation and minimal lobular hepatitis and no evidence for biliary tract disease does not fit well for recurrent hepatitis or acute cellular rejection and should prompt a differential that includes a drug reaction. Finally, EBV hepatitis will be in the differential in some cases and an in situ hybridization for EBV (Epstein-Barr early RNA [EBER]) is a valuable tool.

OTHER PATTERNS OF ACUTE CELLULAR REJECTION

Lobular-Based Rejection

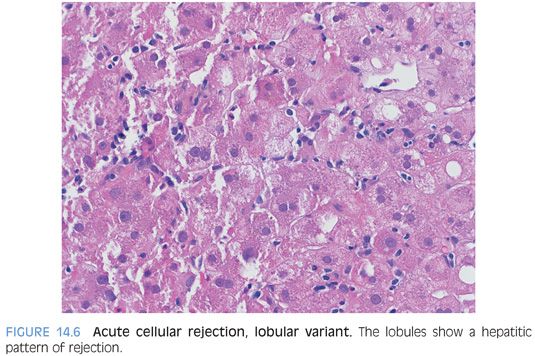

A minimal or mild patchy lobular hepatitis can be seen in many cases of typical acute cellular rejection. However, in a few settings, the lobular hepatitis can dominate the histologic findings, with only mild and nonspecific portal tract changes. The first setting is that of children and the second is that of adults who completely stop taking their medications, going from full immunosuppression to no immunosuppression. This pattern could theoretically occur in other situations too, but it is most commonly seen in these two settings. The biopsy findings in both of these cases probably represent an early pattern that will evolve, if untreated, to a more typical rejection pattern. These cases are important to recognize for proper and prompt treatment. The differential for a lobular pattern of acute cellular rejection includes recurrent chronic viral hepatitis, EBV hepatitis, and a drug reaction.

The lobules show mild to patchy moderate lymphocytic hepatitis with scattered apoptotic bodies and mild Kupffer cell hyperplasia (Fig. 14.6). The portal tracts typically show mild lymphocytic inflammation with no endothelialitis and no or minimal duct injury. The central veins are not involved. Rarely, the lobular inflammatory changes can be accentuated around the canals of Hering, which may appear more prominent than usual.

Central Perivenulitis

Central perivenulitis is an important injury pattern to recognize. The frequency in the literature is not well defined, but one study reported a frequency of 28%.11 This frequency is probably higher than is experienced at many centers and may reflect differences in patient populations, clinical treatment protocols, or histologic definition.

In central perivenulitis, the lobules will have mild hepatocellular loss in zone 3 along with a usually mild lymphocytic inflammation in the zone 3 areas of hepatocyte loss (eFigs. 14.12 and 14.13). Extravasated red blood cells can also be seen in the zone 3 region. However, the endothelium of the central vein will not have typical features of endothelialitis in most cases and often appears essentially normal. Many times, the central perivenulitis will be accompanied by more typical acute cellular rejection changes in the portal tracts, whereas in other cases, the central perivenulitis will be an isolated finding. Isolated central perivenulitis is more common in later allograft biopsies. In both cases, most medical centers and most authors regard these changes as a manifestation of cellular rejection. This pattern of rejection has not been as well studied as typical cellular rejection but appears to respond to antirejection therapy.12 Central perivenulitis is often seen again on repeat biopsies of the same allograft. In some cases, this pattern of injury can also lead to central vein fibrosis and is associated with an increased risk for subsequent ductopenia.11

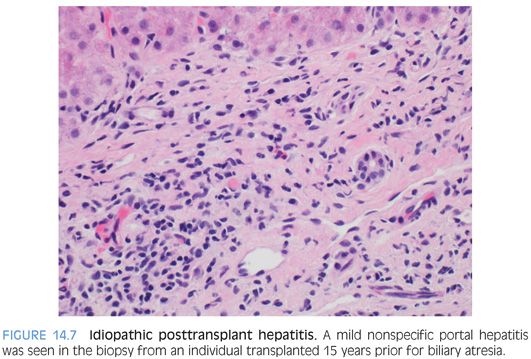

Chronic Hepatitis Pattern

In this pattern, the biopsy shows chronic portal inflammation with no or minimal duct injury and no endothelialitis. The term idiopathic posttransplant hepatitis is also used to describe this pattern of injury. The portal chronic inflammation is typically mild to moderate (Fig. 14.7). The inflammatory cells are predominately lymphocytic, but in some cases, plasma cells can be mildly prominent. Mild interface activity is common, especially in those cases with moderate portal chronic inflammation. This pattern is only recognizable in those individuals transplanted for diseases that do not recur with a hepatitic pattern. As one example, this pattern cannot be confidently identified in those individuals transplanted for chronic hepatitis C. This does not mean this pattern could not occur with patients transplanted for chronic hepatitis C, but the portal changes cannot be distinguished from that of recurrent disease by current histologic methods. Even in cases without a risk of recurrent disease, this pattern remains a challenge—as distinguishing this pattern from a mild drug reaction or other causes of mild nonspecific hepatitis is problematic in many cases. Because of these issues, this pattern remains incompletely defined at all levels: histologic, clinical, prognosis, and management. However, this pattern has been associated with fibrosis progression,13,14 so efforts to identify an etiology are important. Fibrosis risk may be higher when this pattern of injury is associated with elevated autoantibodies, with or without other features of autoimmune hepatitis.15,16

As currently reported in the literature, the chronic idiopathic posttransplant hepatitis pattern probably represents a mixture of disease processes. Although data remains limited, a few general guidelines can help evaluate these cases. First, chronic viral hepatitis and drug effect should be excluded as carefully as possible. In this process, chronic hepatitis E should also be excluded. If the patient was transplanted for fulminant hepatitis A, then chronic hepatitis A should also be excluded.17,18 In those cases in which no cause can be identified, chronic idiopathic posttransplant hepatitis that is also associated with central perivenulitis is the most likely to respond to optimization of immunosuppression.

Plasma Cell–Rich Rejection

Occasional biopsies performed to rule out rejection in the setting of increased enzyme elevations will show a plasma cell–rich infiltrate. If a biopsy shows increased portal plasma cells in the setting of otherwise typical findings of acute cellular rejection, such as duct injury with or without venuliltis, then the findings are most consistent with acute cellular rejection. In these cases, the plasma cell numbers increase roughly in proportion with the severity of the rejection.19 In other cases, the plasma cells may be disproportionately numerous for the overall amount of inflammation. The reasons why some rejection infiltrates have more plasma cells is unclear but presumably represent underlying genetic predisposition to autoimmune type phenomenon. One study found that increased numbers of plasma cells in the native liver were associated with subsequent risk for plasma cell–rich rejection.20 In this study, native livers were examined by randomly selecting five portal tracts with dense inflammation. The livers at highest risk were those with more than 30% plasma cells in at least one portal tract.20

There is a separate group of cases that has a plasma cell–rich pattern of rejection but lack the classic features of duct injury or endothelialitis, although they may have central perivenulitis.21 This group of patients may have preceding or subsequent biopsies that show more typical patterns of rejection. They often have serum autoantibody positivity but at low titers.21 This pattern of rejection responds to corticosteroids but can be difficult to manage and lead to graft failure.20,21 Anecdotally, there seems to be significant center-to-center variability in the frequency of this pattern of rejection.

Interferon-based therapy for recurrent hepatitis C can also trigger a plasma cell–rich variant of rejection,22–24 in particular if the levels of immunosuppression are reduced prior to the interferon-based therapy. In other cases, the plasma cell–rich hepatitis will be associated with the development of other autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus24 and the findings appear to represent a de novo autoimmune hepatitis. Of course, the differential also includes recurrent disease for those individuals transplanted for autoimmune hepatitis.

The therapies for rejection versus recurrent autoimmune hepatitis (or de novo autoimmune hepatitis) are not identical but are broadly similar. In these cases, the histologic findings can be used to suggest that one process is more likely than the other, but clinical management often has to be guided by response to therapy. Recurrent autoimmune hepatitis typically occurs more than 2 years after transplant, whereas most plasma cell–rich rejection cases occur within the first 2 years.21 As noted earlier, autoantibody titers are often negative or low titer in plasma cell–rich rejection versus high titer in true autoimmune hepatitis. Also of note, many cases of plasma cell–rich rejection are associated with prior more typical acute cellular rejection episodes or with current subtherapeutic levels of immunosuppression.

ANTIBODY-MEDIATED REJECTION

Definition

Antibody-mediated rejection occurs when circulating antibodies to donor antigens lead to graft injury. Antibody-mediated rejection is well recognized as clinically important in some allografts, such as the kidney, and clear diagnostic criteria have been developed. This is not the case in the liver, where the frequency, clinical significance, and diagnostic findings are still under investigation. Of note, in the liver, the presence of donor-specific antibodies alone does not clearly predict the development of antibody-mediated rejection. Nonetheless, the diagnosis can only be made with confidence when donor-specific antibodies are present. In addition, the diagnosis also requires clinical or laboratory graft dysfunction, active graft injury with histologic features consistent with antibody-mediated rejection, and compatible C4d staining.

Clinical Findings

Antibody-mediated rejection occurs in a “primary” form, in allograft recipients who have preformed ABO antibodies and develop hyperacute rejection. This pattern is rare. In contrast to hyperacute rejection in other allograft organs, which can occur within minutes after organ reperfusion, hyperacute rejection in the liver can be delayed by several hours or days. Other preformed antibodies that can play a role in antibody-mediated rejection include lymphocytotoxic antibodies and antiendothelial antibodies. With primary antibody-mediated rejection, the graft shows early and often substantial graft dysfunction, usually within the first 2 weeks after transplantation. The secondary form, where de novo antibodies develop after transplantation, has been associated with both acute cellular rejection and with chronic rejection. An excellent, comprehensive review article has recently been published.25

In certain cases, specific targets for antibody-mediated rejection can be identified. In these cases, a donor liver expresses normal liver proteins that are lacking in the recipient, either due to polymorphisms such as with glutathione-S-transferase T1 (GSTT1),26,27 or with inherited genetic disease such as with bile salt export proteins.28 In time, the recipient recognizes these proteins as foreign and this can elicit antibody-mediated rejection. These cases are often considered under the category of de novo autoimmune hepatitis, but they are discussed here because they can also have C4d staining in the portal tracts29 and presumably have an element of antibody-mediated rejection.

Histologic Findings

In severe primary antibody-mediated rejection (“hyperacute rejection”), the endothelium is the primary target and the liver shows endothelial injury, microvascular thrombi, variable sinusoidal dilatation, and congestion. Neutrophils can be prominent in the portal tracts and sinusoids. There can be substantial hemorrhagic liver necrosis. The histologic findings can overlap with ischemia and severe preservation injury, so these need to be excluded. In addition, the histologic findings need to be correlated with the presence of preformed donor antibodies to confidently make the diagnosis.

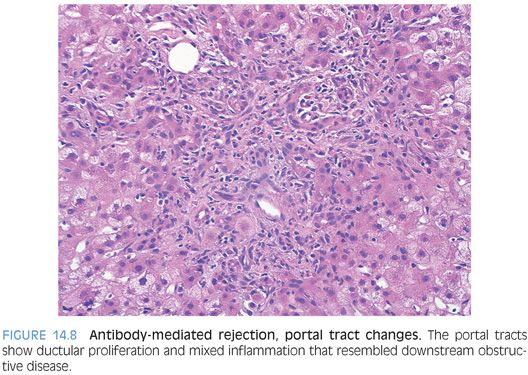

In acute antibody-mediated rejection, the histologic findings remain incompletely defined. However, they can be roughly divided into early changes that can occur within the first week and later changes. The early changes are nonspecific and tend to resemble preservation injury, with zone 3 hepatocyte ballooning, lobular spotty necrosis, and cholestasis.25,30 Later changes can be more striking and can mimic biliary obstruction with portal tract edema, ductular proliferation (Fig. 14.8), and portal neutrophilia.25,31,32 The sinusoids can show varying degrees of neutrophilia in some cases. The lobules may also show cholestasis. Eventually, untreated antibody-mediated rejection can lead to thrombosis of portal veins and hepatic arteries with ischemic necrosis of bile ducts and hepatic parenchyma.

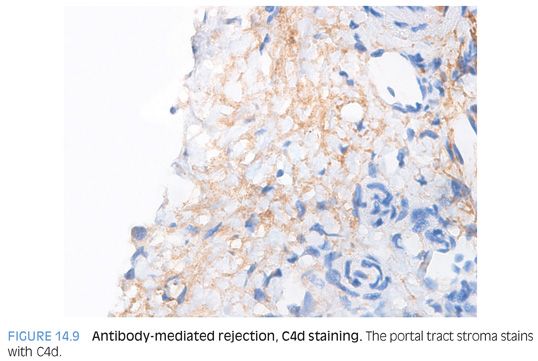

Immunostain Findings

Staining for C4d is used in making the diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection. Many questions remain on the best staining methods (immunohistochemistry vs. immunofluorescence), the best antibody, and the best staining protocol. Immunofluorescence currently appears to be more sensitive.30 Positive C4d controls should also be performed and can include known cases of antibody-mediated rejection in other organs.

C4d staining in isolation is difficult to interpret. However, C4d staining can help confirm a diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection in the setting of donor-specific antibodies, clinical graft dysfunction that is unexplained by other processes, and a biopsy that shows active injury compatible with antibody-mediated rejection—in particular, a pattern that resembles biliary obstruction. C4d staining can be seen in the portal veins, in the sinusoids, and in combined patterns. As a general rule of thumb, immunostaining tends to be stronger in the portal veins and capillaries/stroma of the portal tracts than in the sinusoids (Fig. 14.9). In turn, the sinusoidal staining tends to be stronger than that of the central veins. Which pattern is more sensitive or specific remains unclear, but in general, a diffuse pattern (defined by more than 50% of portal tracts, for example) is more useful for confirming a diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection.25 However, to illustrate that this area of pathology is still incompletely defined, one recent study reported that C4d sinusoidal staining on frozen section is the most reliable method for C4d detection.30