In most cases, the hepatitic injury will resolve after stopping the drug, but it may take months for the liver enzymes to completely normalize. In general, cases with significant cholestasis tend to resolve more slowly than those that are purely hepatitic. A small proportion of idiosyncratic drug reactions can continue with abnormal liver enzymes for more than 6 months after stopping the drug, but histologic evaluation of these cases is rare and there is little evidence for progression to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in most cases.

Histologic Clues to a Drug Reaction

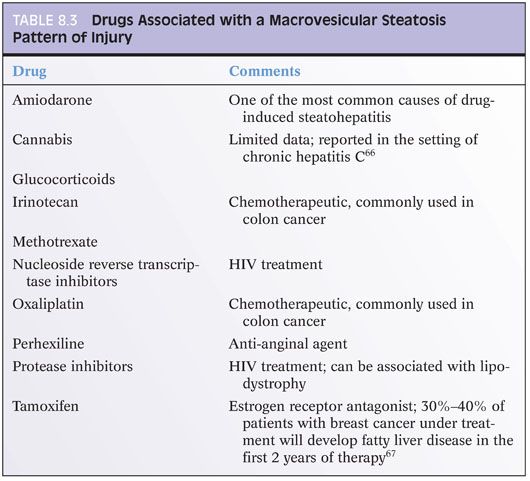

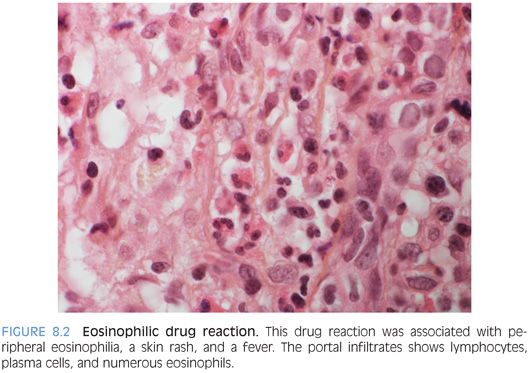

Prominent eosinophils in the portal tracts and/or lobules can suggest a drug reaction of the hypersensitivity type (Fig. 8.2, eFig. 8.1). Although this clue is useful, it is rarely seen because most biopsied drug reactions are of the idiosyncratic type. Bland lobular cholestasis is another potential clue to a drug reaction (Fig. 8.3). This pattern of injury shows lobular cholestasis but no evidence for biliary tract disease, no significant inflammation, and no fibrosis. This pattern is not specific but is most commonly seen as part of a drug reaction, especially if it is associated with an acute onset of liver enzyme abnormalities and the patient is not septic or otherwise severely ill.

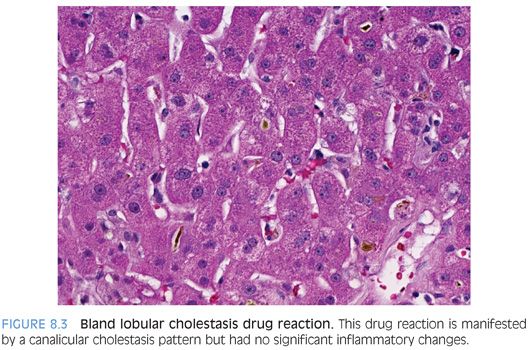

DIRECT TOXINS

Direct toxins cause liver injury in a reproducible and dose-dependent fashion. Examples include acetaminophen, mushroom poisoning, and miscellaneous household and industrial chemicals. The basic pattern of injury is direct necrosis with relatively little inflammation. The surviving hepatocytes often show fatty change with small- and medium-sized fat droplets, cholestasis, and other reactive changes. In most cases, the necrosis tends to have a zone 3 pattern. However, toxicity from phosphorous, ferrous sulfate, and cocaine have all been associated with a zone 1 pattern of necrosis.5,6 Beryllium toxicity has been associated with a zone 2 pattern of necrosis. With more severe injury, the necrosis is often panacinar and no zonation will be evident.

Acetaminophen Toxicity

Acetaminophen toxicity is a classic example of a direct liver toxin, with the degree of injury predicted by the level of exposure. Acetaminophen toxicity is one of the most important causes of acute liver failure and represents up to 50% of cases in the United States and 75% of cases in the United Kingdom. However, in other countries, such as Japan, the frequency is very low.

Acetaminophen toxicity occurs in individuals who intentionally take large quantities at single time points as suicide attempts (approximately 40%). However, an even larger proportion of individuals have unintentional overdoses. Often, the unintentional overdose is in the context of alcohol use or in cases of chronic pain and the use of medications that contain narcotics and acetaminophen. Hepatic injury is usually not seen unless there is more than 7.5 g of exposure, with severe liver damage seen with levels of 15 to 25 g of exposure. However, the toxic threshold can be lower in individuals with fatty liver disease, chronic alcohol consumption, and use of drugs that stimulate the cytochrome P450 enzyme system, including carbamazepine, cimetidine, isoniazid, and phenytoin.

The median alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level is 4,300 IU/L with acetaminophen toxicity, whereas the bilirubin tends to have only a modest elevation of 4 mg/dL. By way of contrast, idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury tends to have lower ALT levels (average of approximately 500 IU/L) but higher bilirubin levels (average around 20 mg/dL). Treatment of acetaminophen toxicity with N-acetylcysteine is very effective when given within the first 24 hours of presentation.

Histologically, the liver shows hepatocyte necrosis that can have a zone 3 distribution in mild cases (Fig. 8.4) but can show panacinar necrosis in more severe cases (eFig. 8.2). The Kupffer cells and endothelial cells are often still alive and are still seen in their normal locations. The remaining hepatocytes are often cholestatic, but there is relative little inflammation in the lobules or portal tracts. The surviving hepatocytes also typically show mild microvesicular steatosis (eFig. 8.3). If the specimen is from a later time point, the areas of necrosis may show mild inflammatory changes and the portal tracts and areas of parenchymal collapse can show a brisk bile ductular proliferation. At these later time points, the Kupffer cells can also show significant iron accumulation, as can the proliferating bile ductules. Although special stains are not needed in most cases, occasionally a special stain to demonstrate the necrosis can be useful for diagnosis or presentations to clinical colleagues. Useful stains include a CD10 or polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), which will show loss of the canalicular staining pattern in the necrotic areas (eFig. 8.4).

ALLERGIC-TYPE DRUG REACTIONS

Allergic-type drug reactions are rarely biopsied because the patient typically has other clinical findings, such as hives or wheezing or a peripheral eosinophilia. However, occasionally, the clinical findings can be diminished or obscured by other comorbid conditions and the liver is biopsied to investigate new-onset hepatitis.

In most cases, the drug exposure will have been within the past few days or weeks. The biopsy shows increased portal tract and sinusoidal eosinophils. The portal inflammation also typically contains mild to moderate patchy lymphocytic inflammation. The lobules can also show mild lymphocytic inflammation and occasional apoptotic bodies.

Of note, cases of otherwise typical chronic viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis can sometimes have a mild prominence in portal eosinophils, so the mere presence of eosinophils does not always indicate a drug reaction. Likewise, a prominence in sinusoidal eosinophils can be seen with peripheral eosinophilia from many different causes and is not always a drug reaction. In these cases, there is minimal or absent lobular injury because the eosinophils are simply passing through the liver sinusoids and their prominence in the biopsy reflects the increased numbers in the blood.

IDIOSYNCRATIC DRUG REACTIONS

Idiosyncratic drug reactions by definition are not dose-related and cannot be predicted on an individual level. Idiosyncratic drug reactions are the most common type of drug reaction seen on liver biopsy. The diagnosis requires exclusion of acute viral hepatitis (A, B, C, and E) and autoimmune hepatitis. Several broad patterns can be seen and are described in more detail below. Often, more than one pattern can be seen in any given biopsy. Also of note, although drug reactions for some drugs tend to all look very similar histologically, there can be wide variations in histologic findings for the vast majority of drug reactions, and finding a “typical pattern” is helpful but not necessary to diagnose a drug reaction. Most idiosyncratic drug reactions are not associated with significant fibrosis, and advanced fibrosis in most cases suggests an alternative injury process.

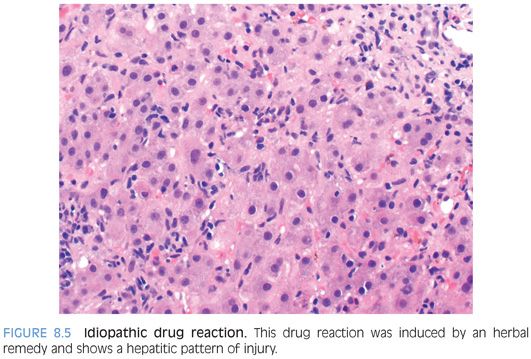

Hepatitic Pattern

The hepatitic pattern has inflammatory changes that resemble acute hepatitis, with lobular inflammation that can range from mild to marked, and is associated with variable degrees of lobular disarray and apoptotic hepatocytes (Fig. 8.5). The inflammation is predominately lymphocytic. Lobular cholestasis can be seen with more severe degrees of lobular hepatitis as well as zone 3 necrosis (eFig. 8.5). The portal tracts show predominately lymphocytic inflammation, but occasional plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils are common. Interface activity can be present, in particular with moderate to marked portal inflammatory changes.

The differential for a hepatitic pattern of injury is largely that of viral hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis. Correlation with serologic studies, viral studies, and drug history will allow appropriate classification in most cases. Of note, the histologic findings in acute viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and hepatitic drug reactions have sufficient histologic overlap that in most cases a diagnosis cannot be confidently provided based solely on histology. Specifically, plasma cells, interface activity, and zone 3 predominant inflammation can be seen in all three and are not etiologically specific. However, the biopsy provides unique, important, and useful information when combined with the serologies and clinical history.

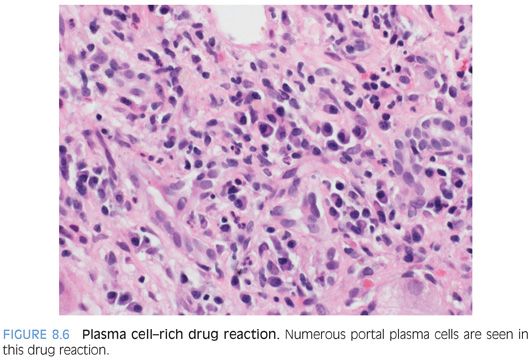

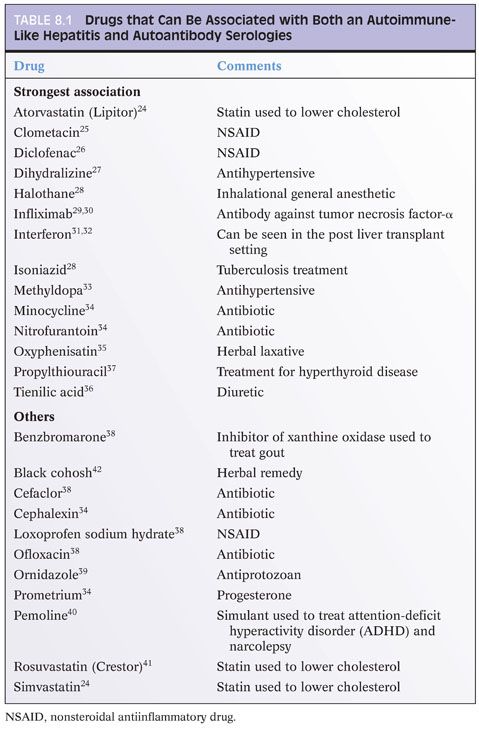

Also of note, several idiosyncratic drug reactions can have a plasma cell–rich hepatitic pattern that histologically closely mimics autoimmune hepatitis (Fig. 8.6, eFig. 8.6) and can be associated with elevated serum antinuclear antibody (ANA) and/or smooth muscle antibody (SMA) titers. These drugs include minocycline (used to treat acne), methyldopa (used to treat hypertension), clometacin (antiinflammatory drug), and nitrofurantoin (used to treat urinary tract infections) (Table 8.1). These drug reactions can start soon after beginning the medication or can take several years to develop.

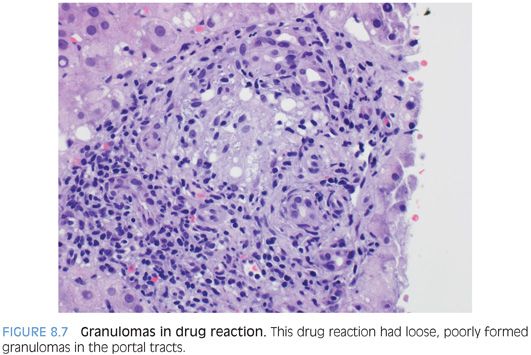

Granulomatous Pattern

Granulomas in drug reactions are commonly associated with lymphocytic inflammation of the portal tracts and lobules. Granulomas can be found in either or both of the portal tracts and lobules (Fig. 8.7). Occasionally, granulomas can involve the bile ducts. Many drug-associated granulomas are associated with significant (moderate to marked) hepatitic changes, but occasionally, the granulomas can be the main histologic finding. The granulomas can be loose and poorly formed or well-formed epithelioid granulomas. The granulomas can be immunostained with CD68, but this is rarely necessary. Stains to rule out fungal and acid-fast infections are important to perform. Polarizing granulomas can also be helpful to rule out foreign body granulomas. Nonetheless, in most cases, the granulomas will be negative, and you will have to polarize a lot of cases to find the rare case of granulomatous hepatitis associated with foreign material.

The differential for granulomas of the liver is broad. Most granulomas seen in liver biopsies are not drug-related but instead are idiopathic, sarcoidosis-related, infection-associated, or seen in the setting of primary biliary cirrhosis.7 Drug-induced granulomas are generally not associated with fibrosis (as can be seen in sarcoidosis) and typically do not show central necrosis, a finding that would favor infection. Evaluation for primary biliary cirrhosis should include serum testing for antimitochondrial antibodies (AMAs) and examination of the biopsy for florid duct lesions, bile duct loss, or fibrosis—all features that would favor primary biliary cirrhosis over a drug reaction. There are no immunostains that will differentiate types of granulomas in different disease processes.

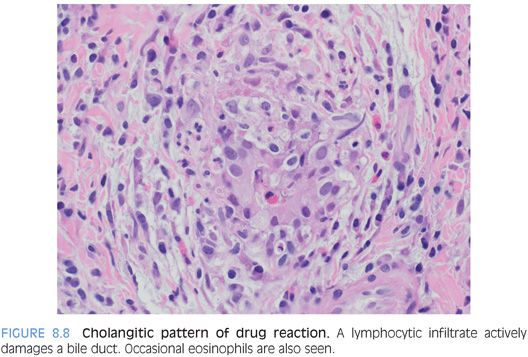

Cholangitic Pattern

The cholangitic pattern shows active bile duct injury, with lymphocytosis of the bile duct epithelium, reactive epithelial changes, and apoptotic epithelial bodies (Fig. 8.8). The inflammation is often mixed with lymphocytes and neutrophils. There also can be a histiocyte-rich pattern that is vaguely granulomatous, often in association with bile duct injury. This cholangitic pattern is most commonly seen with antibiotics.

Cholestatic Pattern

Varying degrees of cholestasis can be present in biopsies with a marked hepatitis pattern or with a cholangitic pattern, but this section is focused on the injury pattern that is primarily lobular cholestasis without active bile duct injury or significant hepatitis. This pattern of injury is most commonly seen with oral contraceptives or anabolic steroids but can also be seen with a wide range of other medications. The cholestasis often has a zone 3 predominance, and the bile can be seen in the hepatocyte cytoplasm or in the bile canaliculi. Bile is not seen in the bile ducts, and there is typically no or minimal ductular reaction. Lobular cholestasis can persist for several months after discontinuing the offending drug.

The differential for bland lobular cholestasis includes sepsis, heart failure, hypothyroidism, and individuals who are critically ill, for example, in intensive care units. In most of these settings, biopsies are not performed because the clinical findings provide an explanation for the liver dysfunction. However, biopsies are occasionally performed to rule out additional causes of liver disease.

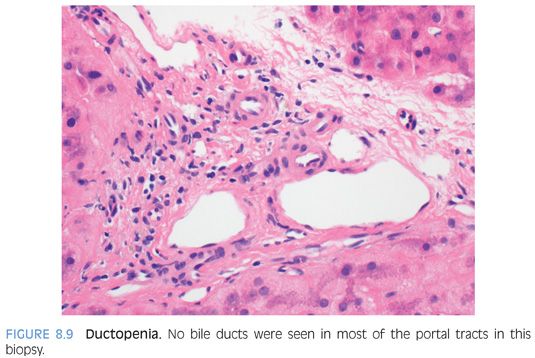

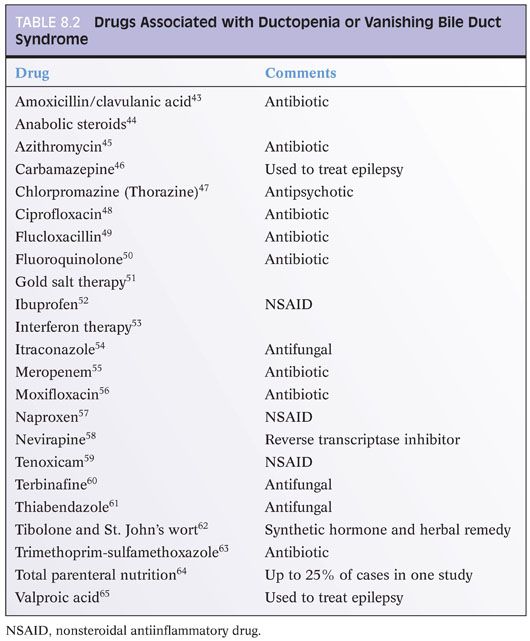

Ductopenic Pattern

Loss of intrahepatic bile ducts is an important pattern of drug injury (Fig. 8.9 and Table 8.2). This pattern can be very subtle, and cytokeratin immunostains can be helpful in highlighting the bile ducts and quantify any duct loss. When evaluating the biopsy, the size of the portal tract should also be taken into account. Any loss of bile ducts in large- or medium-sized portal tracts is abnormal, although approximately 50% of smaller portal tracts should have bile duct loss to confidently diagnosis ductopenia on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains. Looking for unpaired hepatic arteries can improve the detection of bile duct loss.8 In cases of drug-induced ductopenia, the remaining ducts often show atrophic type changes and the overall findings tend to be similar to that of chronic rejection of the liver allograft. The biopsies also will typically show mild nonspecific portal lymphocytic inflammation and may show lobular cholestasis. The degree of lobular cholestasis depends on the extent and duration of the ductopenia. In all cases, imaging of the biliary tract should be performed to exclude duct loss to secondary to chronic obstructive injury. The biopsies may also show cholate stasis but generally will show little or no ductular reaction, no bile duct duplication, no onion skinning fibrosis, and no fibro-obliterative duct lesions. If any of these latter changes are present, the ductopenia is less likely to be drug-related. Likewise, significant fibrosis is typically not part of the drug-associated ductopenic pattern of injury and would favor an alternative form of chronic biliary tract disease.

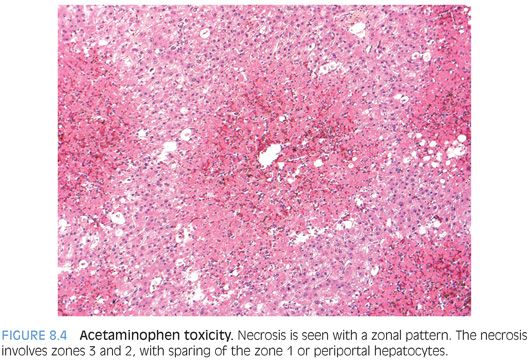

Fatty Pattern

Drug reactions can cause both a macrovesicular and microvesicular pattern of injury. Overall, an estimated 2% of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease cases are drug-related.3 The diagnosis of a macrovesicular steatosis pattern of drug injury requires exclusion of other diseases including the metabolic syndrome, alcohol intake, Wilson disease, celiac disease, protein malnutrition, and cystic fibrosis. Steroids are one of the more commonly encountered drug-induced causes of steatosis, but there are many others (Table 8.3). Steatohepatitis, with ballooned hepatocytes and Mallory hyaline, is rarely seen other than with amiodarone or irinotecan.