Symptom

Prevalence (%)

Obstructed defecation

75–100

Manual assistance of defecation

20–75

Rectal pain

12–70

Rectal bleeding

20–60

Incontinence

10–30

Rectocele can be classified according to its position: low, middle, or high; and/or their size: small (< 2 cm), medium (2–4 cm), or large (4 cm). Size is measured anteriorly from a line drawn upward from the anterior wall of the anal canal on proctography [4]. It can also be classified into three clinical stages at straining during defecation proctography (Table 18.2).

Table 18.2

Classification of rectocele

I | Digitiform rectocele of single hernia through the rectovaginal septum |

II | Big sacculation, lax rectovaginal septum, anterior rectal mucosal prolapse, deep pouch of Douglas |

III | Rectocele associated with intussusception and/or prolapse of the rectum |

Surgery should be considered when conservative therapy fails and careful patient selection, based on an accurate morphofunctional assessment, is crucial to obtain a satisfactory outcome [5].

The purposes of surgical repair in the management of rectocele repair are essentially the restoration of normal vaginal anatomy and the restoration or maintenance of normal bladder, bowel, and sexual function.

Transperineal repair of the fascial defect may provide restoration of normal anatomy and symptomatic relief. A variety of synthetic and nonsynthetic graft materials have been used in rectocele repair to enhance anatomical and fuctional results, and improve long-term outcomes. Symptomatic rectocele results in obstructed defecation and constipation. Surgical repair may provide symptomatic relief.

Recent advances in pelvic reconstructive surgery are due, in part, to the availability of new graft materials that allow reinforcement and repair of large pelvic fascial defects, minimizing adverse graft-related effects and postoperative complications [6].

18.2 Pretreatment Evaluation

Although rectoanal intussusception may be observed during physical examination, it is much more likely to be detected during defecography, which remains the most useful diagnostic tool when applied to a symptomatic subject. Defecography is crucial to document the presence of anatomical changes stemming from the symptoms of obstructed defecation. In particular, it is fundamental in order to distinguish between rectoanal intussusceptions and rectal internal mucosal prolapse, and to describe and quantify rectoanal intussusception. It also reveals the presence of other abnormalities, such as the presence of a rectocele or weakened pelvic floor with perineal descent, or failure of the puborectalis to relax during straining and evacuation, which is often associated with pelvic perineal dyssynergia. Rectoanal intussusception, as reported in the literature, appears to be the main reason for obstructed defecation. Defecography seems to be the examination of choice because it allows assessment of not only the rectum, but also the rectovaginal space and vagina in order to investigate the presence of an associated enterocele, or failure of the medium and/or anterior compartment.

However, it should be noted that a transient infolding of the rectal wall can occur during evacuation, even in asymptomatic subjects. In more complex cases in which all pelvic compartments are involved, the introduction of dynamic magnetic resonance imaging has opened up the possibility of better understanding the relationships between the pelvic floor organs and the structures involved. Pelviperineal neurophysiological tests (electromyographic recording of the anal sphincter) and anorectal manometry are also useful, particularly for the evaluation of sphincter tone. Anorectal manometry is very important and it can detect pelviperineal dyssynergia; it provides the basic diagnostic criteria for deciding to carry out pelviperineal rehabilitation.

18.3 Management and Contraindications

Specific selection criteria for the surgical repair of a rectocele are the subject of debate. Surgical repair has been recommended when the rectocele is greater than 3 cm in depth, if there is significant barium trapping or defecography, or if digital assistance of defecation is frequently necessary for satisfactory emptying [8, 9]. However, multiple studies have shown no correlation between the size of a rectocele or the extent of barium trapping and the degree of symptoms or outcome of rectocele repair [10, 11]. Some authors [5, 6, 12] have shown that the main causes of functional failure after classical rectocele repair are:

1.

Rectal intussusception

2.

Rectal prolapse

3.

Enterocele

Therefore it is mandatory that rectocele correction via the transperineal approach must be used only in simple type 1 rectocele, otherwise it would be impossible to correct a rectal intussusception or rectal prolapse by repairing only the fascial defect and normal anatomy would not be restored.

18.4 Surgical Treatment

Anatomofuctional abnormalities can be independent of clinical symptoms, and their surgical treatment must be considered carefully. The risk following careful morphological and physiological investigation is overestimation of the disturbance, and overindication for treatment. Stool softeners, laxatives, and behavioral measures help some patients, but often do not offer satisfactory long-term results. However, the most severely symptomatic patients may be candidates for surgery.

The aims of surgical repair in the management of rectocele repair are essentially: the restoration of normal vaginal anatomy, and the restoration or maintenance of normal bladder and sexual function. Formerly, colorectal surgeons used traditional methods to repair rectoceles per anus by mucosal resection and anterior rectal wall plication. Gynecologists adopted a vaginal approach, excising part of the posterior vaginal wall combined with an anterior levatorplasty [13].

There are significant drawbacks to both techniques. Transanal repair has been shown to significantly reduce both resting and squeeze pressures postoperatively, despite minimizing the amount of anal retraction [14], and it results in a higher rate of enterocele recurrence compared with posterior vaginal wall repair. Conversely, posterior vaginal wall repair may result in dyspareunia and higher postoperative analgesic requirement, and it might not eliminate the symptom of incomplete evacuation [15]. Richardson [16] recognized that repair of the fascial defect is more important than imbricating the vaginal or rectal walls and was the first to describe repair via a posterior vaginal wall incision and apposition of edges of the defect with interrupted sutures. Consequently, augmentation of transvaginal repair with mesh interposition has been advocated [12, 17, 18].

18.4.1 Technique

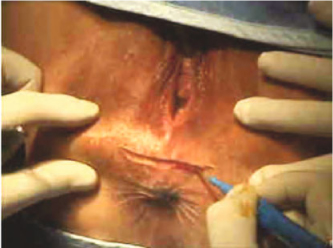

A transverse perineal incision is made (Fig. 18.1). The plane between the external anal sphincter and the posterior vaginal wall is developed with diathermy to ensure meticulous hemostasis. The dissection is extended to the vaginal apex to expose the rectocele, the perirectal fascia, and the levator arc (Fig. 18.2).