The Nonneoplastic Anus

Embryology

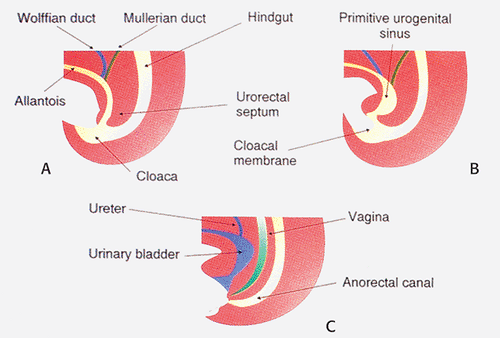

The anal canal develops from the distal hindgut. Early in development, the hindgut, allantois, and urogenital tracts end in a common cloaca. Later, the urogenital septum divides the hindgut into the anterior urogenital and posterior gastrointestinal compartments. Distally, the cloacal membrane, composed of an ectodermal and endodermal layer, separates the endodermally derived hindgut from the ectoderm. It ruptures at approximately the seventh week of gestation, at which time the urogenital septum is almost completely formed and normal anatomic relationships are established. Cloacal membrane remnants are converted to the urogenital and anal membranes. These membranes eventually dehisce, allowing orifices to be established for the urogenital and anal structures. Mesoderm later invades the perianal region, forming the external sphincter. The dentate line and anal papillae are remnants of the anal membrane.

If the cloacal membrane persists for longer than normal, the inferior abdominal muscles and the pubic bones develop in a lateral unfused position. If the cloacal membrane ruptures before the urogenital septum separates the bladder from the hindgut, cloacal exstrophy occurs (1). Incomplete separation of the cloaca results in an abnormal connection between the rectum and bladder, urethra, or vagina and imperforate anus (1). Figure 15.1 shows the embryology of the anus with the progressive development of the cloaca and formation of the primitive urogenital sinus with eventual separation of the urogenital sinus into the urinary bladder and the anorectal canal.

Definitions

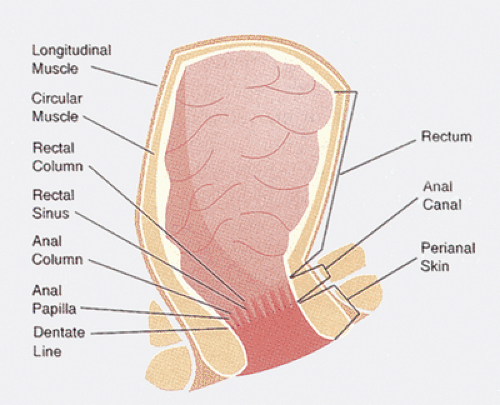

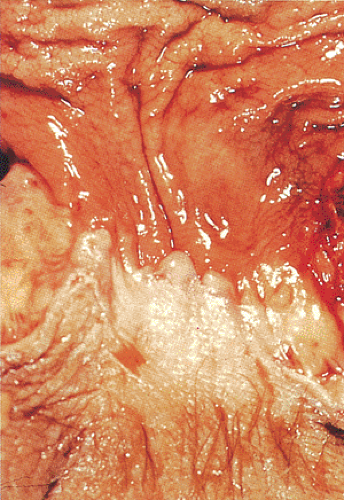

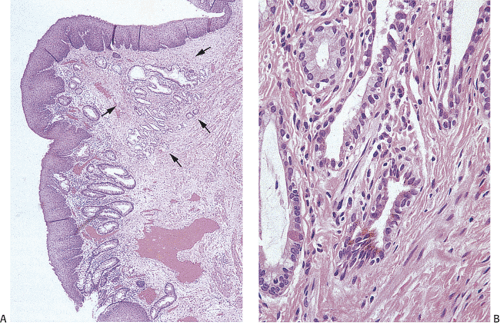

In the most commonly accepted definition, the anal canal extends from the perineal skin to the lower end of the rectum at the upper border of the internal sphincter at the anorectal ring. It ranges in length from 3 to 4 cm (2,3). The anal verge marks the junction of the anal canal and the perineal skin. It is identified microscopically by the appearance of cutaneous adnexa. The dentate or pectinate line marks the junction between the anal canal and the rectum (Fig. 15.2) and it lies in the center of the anal canal. Sixteen mucosal longitudinal folds, known as the anal columns of Morgagni, and homologous structures in the lower rectum, known as the rectal columns of Morgagni, cover the underlying blood vessels. These are separated by the anal sinuses or the sinuses of Morgagni. The anal columns connect to one another at the dentate line by anal or semilunar valves. Anal papillae are toothlike, raised projections located on the top of the anal columns that represent ridges of squamous mucosa directly joining the rectal mucosa. Both anal crypts and papillae show marked individual variations and they are often absent. Under the valves, the mucosa joins the hairless skin of the transitional zone in the irregular pectinate line (Fig. 15.3). The external anal sphincter consists of voluntary skeletal muscle arranged as a tube surrounding the internal sphincter. The internal anal sphincter represents the terminal end of the circular smooth layer of the muscularis propria and contains fascicles of involuntary smooth muscle fibers ensheathed in connective tissue. The conjoined longitudinal coat represents the most caudal extension of the longitudinal coat joined by a few striated muscle fibers from the levator ani. It traverses the anal canal between the internal and external sphincters. The internal anal sphincter plays an important role in anal continence and maintenance of resting anal canal pressure.

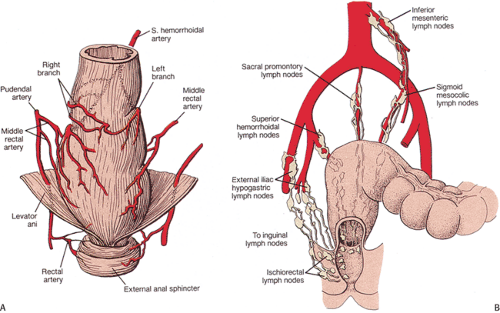

The dual origin of the vascular supply of the anal canal reflects its dual embryology. Most of the anal canal is supplied by the rectal arteries, a continuation of the inferior mesenteric artery. The inferior anal canal is supplied by the inferior rectal arteries, branches of the internal pudendal arteries. The mucocutaneous junction forms a watershed zone between these two vascular supplies. Terminal vascular branches form tiny arteriovenous anastomoses with the submucosal plexus (Fig. 15.4). Above the dentate line, the vessels form a series of hollow communicating spaces surrounded by connective tissue in a structure that resembles a glomerulus. This system is known as the corpus cavernosum recti.

Venous drainage of the superior anal canal is via the superior rectal veins, tributaries of the inferior mesenteric vein. Above the mucocutaneous level, veins drain into the portal venous system. Below this, veins drain into the pudendal veins. The lymphatic drainage of the proximal

two thirds of the anal canal is into the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes. Distal rectal lymphatics drain laterally along the course of the inferior or medial hemorrhoidal vessels into the para-aortic lymph nodes ending in the hypogastric, obturator, and internal iliac nodes. Alternatively, they follow the superior rectal artery to drain into nodes in the sigmoid mesocolon near the origin of the inferior mesentery artery (Fig. 15.4). Distally, the lymphatics have a more complex arrangement. Some anal canal lymphatics connect with rectal lymphatics (4); others cross the anal verge and pass along the genital femoral sulcus on either side, terminating in the inferomedial superficial inguinal lymph nodes (Fig. 15.4) (5). The lymphatics of the lower anal canal drain to the inguinal lymph nodes. Occasionally, connections exist with the common iliac, middle, and lateral sacral, lower gluteal, external iliac, and deep inguinal nodes (6). This organization is reflected in the metastatic spread of anal tumors (Fig. 15.4).

two thirds of the anal canal is into the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes. Distal rectal lymphatics drain laterally along the course of the inferior or medial hemorrhoidal vessels into the para-aortic lymph nodes ending in the hypogastric, obturator, and internal iliac nodes. Alternatively, they follow the superior rectal artery to drain into nodes in the sigmoid mesocolon near the origin of the inferior mesentery artery (Fig. 15.4). Distally, the lymphatics have a more complex arrangement. Some anal canal lymphatics connect with rectal lymphatics (4); others cross the anal verge and pass along the genital femoral sulcus on either side, terminating in the inferomedial superficial inguinal lymph nodes (Fig. 15.4) (5). The lymphatics of the lower anal canal drain to the inguinal lymph nodes. Occasionally, connections exist with the common iliac, middle, and lateral sacral, lower gluteal, external iliac, and deep inguinal nodes (6). This organization is reflected in the metastatic spread of anal tumors (Fig. 15.4).

Histologic Features

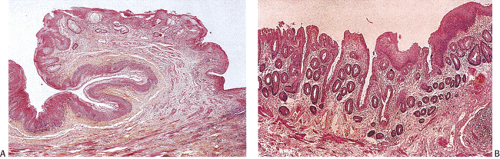

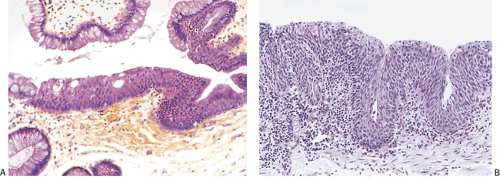

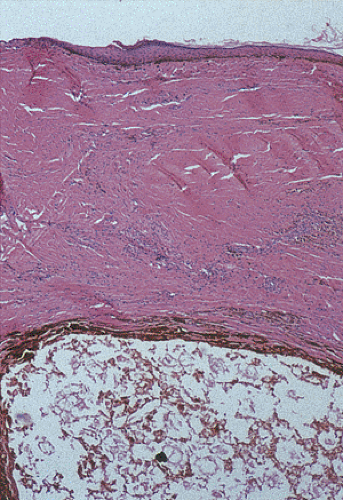

The anal canal mucosa contains four distinctive zones: (a) the colorectal zone immediately distal to the rectum (Fig. 15.5); (b) the transitional zone, roughly corresponding to the area of the anal columns with its distal border approximately at the level of the anal valves and sinuses; (c) the smooth zone

below the anal columns covered by uninterrupted nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium devoid of skin appendages (Fig. 15.6); and (d) the distal zone, composed of keratinizing squamous epithelium. The lower anal canal ends at the anal verge, where the squamous mucosa merges with perianal skin. The squamous mucosa of the anal canal lacks the hair and skin appendages seen in the perianal skin.

below the anal columns covered by uninterrupted nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium devoid of skin appendages (Fig. 15.6); and (d) the distal zone, composed of keratinizing squamous epithelium. The lower anal canal ends at the anal verge, where the squamous mucosa merges with perianal skin. The squamous mucosa of the anal canal lacks the hair and skin appendages seen in the perianal skin.

FIG. 15.4. Normal anatomy. A: Arterial blood supply of rectum. (Adapted from Grant JCB. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1962.) B: Lymph node drainage of the anus. |

The mucosa of the colorectal zone resembles rectal mucosa except that the crypts may appear shorter and more irregular (Fig. 15.5). The transitional zone has irregular outlines and varying locations and extents (7). The cells form four to nine layers and contain transitional, intermediate, or cloacogenic epithelium (Fig. 15.7). The basal layer contains the proliferative compartment. Basal cells are small with

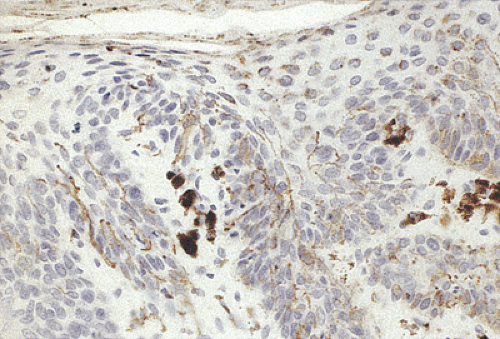

nuclei arranged perpendicularly to the basement membrane. The junction with the underlying tissues is sharp and abrupt. The shape of intermediate cells is usually between that of basal cells and surface cells. Surface cells have a polygonal, columnar, cuboidal, or flattened shape (Fig. 15.7) and resemble bladder or immature metaplastic squamous epithelium, especially when they contain sparse mucus. They sometimes resemble immature goblet cells (8). Mature goblet cells may also be present. The cells in this zone express cytokeratins (CKs) 7 and 19, but not cytokeratin 20 (9). Mitoses are rare unless there has been mucosal injury. Squamous epithelium often covers the anal columns. Melanocytes may be present in this zone, although these are more prominent in the anal squamous epithelium (10). Endocrine cells lie above the dentate line in the colorectal mucosa, in the transitional mucosa, in anal ducts and glands, in crypts, and in perianal sweat glands (11).

nuclei arranged perpendicularly to the basement membrane. The junction with the underlying tissues is sharp and abrupt. The shape of intermediate cells is usually between that of basal cells and surface cells. Surface cells have a polygonal, columnar, cuboidal, or flattened shape (Fig. 15.7) and resemble bladder or immature metaplastic squamous epithelium, especially when they contain sparse mucus. They sometimes resemble immature goblet cells (8). Mature goblet cells may also be present. The cells in this zone express cytokeratins (CKs) 7 and 19, but not cytokeratin 20 (9). Mitoses are rare unless there has been mucosal injury. Squamous epithelium often covers the anal columns. Melanocytes may be present in this zone, although these are more prominent in the anal squamous epithelium (10). Endocrine cells lie above the dentate line in the colorectal mucosa, in the transitional mucosa, in anal ducts and glands, in crypts, and in perianal sweat glands (11).

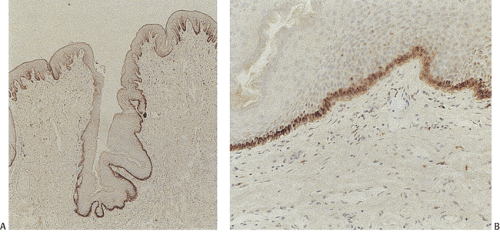

FIG. 15.6. Anal zone showing the presence of nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium. The underlying submucosa is densely fibrotic. |

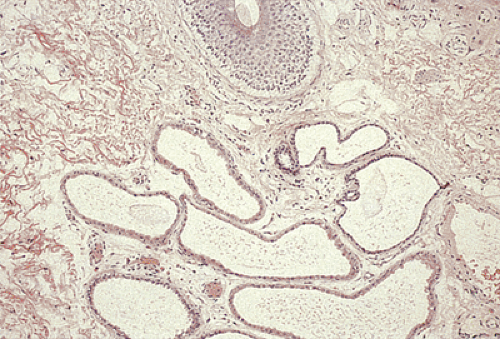

Anal glands discharge into the anal crypts through four to eight long tubular anal ducts (Fig. 15.8) that follow a tortuous course through the lamina propria before penetrating the internal sphincter musculature. Occasionally, anal ducts extend upward above the level of the anal valves, explaining the origin of certain unusual submucosal neoplasms in the proximal anal canal (see Chapter 16). The epithelial lining of the ducts varies, often appearing squamous at the gland opening, transitional with or without cylindric glands in the middle, and simple columnar in its deepest part. Transitional epithelium contains four to six cell layers at the duct origin and two to three cell layers when the ducts penetrate the muscle. Goblet cells are present in large numbers, particularly in their terminal portions before they enter the anal crypts. Anal glands are strongly positive for CK7, but negative for CK20. A characteristic feature of the anal glands is the presence of intraepithelial microcysts.

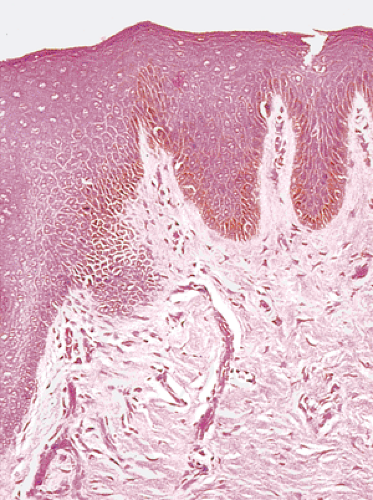

The nonkeratinizing epithelium of the anal canal changes into keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium with numerous melanocytes at the anal verge (Fig. 15.9). Dendritic pigmented cells may also be quite prominent, extending into the suprabasal region (Fig. 15.10). The skin immediately around the anus forms the “zona cutanea.” Sweat glands are

absent from the area immediately bordering the anus, but an elliptical zone measuring 1.5 cm in width lying at a distance of 1 to 1.5 cm from the anus contains simple tubular glands called circumanal glands (Fig. 15.11). Anogenital sweat glands have a long excretory duct opening at the skin surface and a wide coiled secretory part with multiple lateral extensions that form diverticula and branches. The ducts are lined by a two-layered pseudostratified epithelium and myoepithelium and by a luminal layer of tall columnar cells with conspicuous snouts (12).

absent from the area immediately bordering the anus, but an elliptical zone measuring 1.5 cm in width lying at a distance of 1 to 1.5 cm from the anus contains simple tubular glands called circumanal glands (Fig. 15.11). Anogenital sweat glands have a long excretory duct opening at the skin surface and a wide coiled secretory part with multiple lateral extensions that form diverticula and branches. The ducts are lined by a two-layered pseudostratified epithelium and myoepithelium and by a luminal layer of tall columnar cells with conspicuous snouts (12).

The submucosal connective tissue of the upper anal canal is loose, but in the pecten, denser fibroelastic tissue anchors the epithelium to the superficial portion of the internal sphincter, creating a submucosal barrier at the dentate line. The internal venous plexus in the proximal two thirds of the anal canal may give the mucosa a plum-colored or purplish appearance. This plexus is modified into three specialized vascular anal cushions in the left lateral, right anterior, and right posterior zones of the anal canal. These consist of submucosal anastomosing networks of arterioles and venules with arterial venous communications that have a resemblance to erectile tissue (13).

Congenital Anomalies

Anorectal malformations are among the most common gastrointestinal (GI) congenital abnormalities, affecting 1 in every 2,000 to 5,000 live-born infants (14,15). They vary from minor, narrowing defects to serious, complex defects. Anal atresia occurs in many different syndromes (Table 15.1), and 22% to 72% of patients have associated anomalies affecting the vertebrae, gastrointestinal tract, and urologic and genital systems (14,16). The most common defects are the VATER- or VACTERL-associated anomalies (see Chapter 2). The VATER association includes vertebral defects, anal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula, esophageal atresia, and radial and renal abnormalities (16). Cardiac defects, a single umbilical artery, and prenatal growth deficiency may also be present. In the Townes-Brocks syndrome,

an autosomal dominant condition, patients have two or more of the following manifestations: (a) anorectal malformation (imperforate anus, anteriorly placed anus, or anal stenosis); (b) hand malformations (preaxial polydactyly, broad bifid thumb, or triphalangeal thumb); and (c) external ear malformations (microtia, i.e., “satyr” or “lop” ear; preauricular tags or pits) with sensorineural hearing loss. Additionally, urinary tract malformations, mental retardation, and a pericentric inversion of chromosome 16 have been described (17,18). It is unclear whether syndromes with similar abnormalities, such as the VATER, caudal regression, or sacral agenesis syndromes, are distinct and different syndromes or variations of the same one. The Currarino triad combines with congenital anorectal stenosis, a scimitar-shaped sacral defect, and a presacral mass. The disorder is familial in approximately 50% of cases (19). Most frequently, the presacral mass is either an anterior sacral meningocele or benign teratoma.

an autosomal dominant condition, patients have two or more of the following manifestations: (a) anorectal malformation (imperforate anus, anteriorly placed anus, or anal stenosis); (b) hand malformations (preaxial polydactyly, broad bifid thumb, or triphalangeal thumb); and (c) external ear malformations (microtia, i.e., “satyr” or “lop” ear; preauricular tags or pits) with sensorineural hearing loss. Additionally, urinary tract malformations, mental retardation, and a pericentric inversion of chromosome 16 have been described (17,18). It is unclear whether syndromes with similar abnormalities, such as the VATER, caudal regression, or sacral agenesis syndromes, are distinct and different syndromes or variations of the same one. The Currarino triad combines with congenital anorectal stenosis, a scimitar-shaped sacral defect, and a presacral mass. The disorder is familial in approximately 50% of cases (19). Most frequently, the presacral mass is either an anterior sacral meningocele or benign teratoma.

TABLE 15.1 Selected Abnormalities Associated with Anal Atresia | |

|---|---|

|

Anorectal anomalies result from arrested development of the caudal region of the gut during fetal life. When the urorectal septum fuses abnormally with the cloacal membrane or when the anal and genital tubercles develop abnormally, the rectum opens in abnormal spots in the perineum or female external genitalia. Thus, many anal anomalies involve stenosis, occlusive membranes, or agenesis with or without fistulas to the perineal skin, urethra, bladder, vulva, or vagina. Their classification relies on the relationship of the terminal bowel to the levator muscles that form the pelvic diaphragm (Table 15.2) (20). These anomalies are high or supralevator deformities when the bowel ends above the pelvic floor and low or translevator deformities when the bowel ends below the pelvic floor. High anorectal malformations are less common than the low type, but the high type more frequently associates with other anomalies (21).

The etiology of these defects remains uncertain. Vascular accidents are postulated to cause localized defects (22). Mesodermal abnormalities may explain patterns of multiple malformations. Diabetes and drug ingestion (thalidomide, phenytoin, and Tridione) are more common in mothers of infants with anorectal malformations (21,22,23), while occupational exposures to potential teratogens are more common in fathers of children with anorectal malformations. Other potential etiologic associations include maternal AIDS, exposures to x-rays, severe trauma, a retained intrauterine device, gestational age <38 weeks, and Down syndrome (24).

Animal models that disrupt the SONIC hedgehog signal transduction pathway lead to a spectrum of developmental anomalies that strongly resemble those present in the VACTERL syndrome, suggesting that they play a role in the development of the VACTERL complex in humans (25,26). (Sonic hedgehog is an endoderm-derived signaling molecule that induces hindgut mesodermal gene expression.) Cases of Townes-Brocks syndrome (TBS) are often sporadic, but mutations in the gene encoding the SALL-1 zinc finger transcription factor (27) may explain the familial form of the disease. Further, the diagnosis can be confirmed by finding the mutation (28). Recently, a gene responsible for the Currarino triad has been mapped to 7q36, near the locus of the gene for holoprosencephaly (29).

TABLE 15.2 Classification of Anorectal Malformations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Imperforate Anus

Imperforate anus results from failure of the cloacal membrane to perforate. Consequently, the anus does not open

normally into the perineum (Fig. 15.12). Imperforate anus more commonly affects males than females, and can be divided into four major groups: (a) stenosis alone (11%), (b) imperforate anus with only a thin membrane separating the anus and rectum (4%), (c) imperforate anus with a widely separated anus and rectum (76%), and (d) normal anus with the rectum ending some distance above it (9%) (14,30). Fistulae often form between the rectum and the urogenital system. In males, the fistulae tend to be urinary (urethra, 25%; bladder, 33%; perineum, 42%), and in females, rectourinary and rectogenital (vaginal, 84%; perineum, 14.5%; bladder, 1.5%). Rarely, the rectum opens to the scrotum, the undersurface of the penile shaft, or the prepuce (31). Patients with imperforate anus may also have an associated hyperreflexic or atonic urinary bladder (32).

normally into the perineum (Fig. 15.12). Imperforate anus more commonly affects males than females, and can be divided into four major groups: (a) stenosis alone (11%), (b) imperforate anus with only a thin membrane separating the anus and rectum (4%), (c) imperforate anus with a widely separated anus and rectum (76%), and (d) normal anus with the rectum ending some distance above it (9%) (14,30). Fistulae often form between the rectum and the urogenital system. In males, the fistulae tend to be urinary (urethra, 25%; bladder, 33%; perineum, 42%), and in females, rectourinary and rectogenital (vaginal, 84%; perineum, 14.5%; bladder, 1.5%). Rarely, the rectum opens to the scrotum, the undersurface of the penile shaft, or the prepuce (31). Patients with imperforate anus may also have an associated hyperreflexic or atonic urinary bladder (32).

FIG. 15.12. Picture of a male infant with anal atresia. Note the absence of an opening from the anal canal onto the perineum. |

Imperforate anus also occurs in the urorectal septum malformation sequence, a rare congenital malformation affecting females that is characterized by ambiguous external genitalia, disordered/malformed internal genitalia, and imperforate anus, vagina, and urethra. Other abnormalities include renal agenesis or dysplasia, pulmonary hypoplasia, congenital heart defects, and vertebral anomalies (33). The thymic-renal-anal-lung dysplasia syndrome is an autosomal recessive abnormality characterized by a unilobed or absent thymus, renal and ureter agenesis/dysgenesis, intrauterine growth retardation, and imperforate anus (34). Renal, anal, and lung dysplasia is shared with three syndromes: Fraser-Jacquier-Chen (35), Pallister-Hall (PH) (36), and Smith-Lemli-Opitz II (37). Imperforate anus may also complicate prune belly syndrome (38), Eagle-Barrette syndrome (39), or the OEIS complex (omphalocele-exstrophy-imperforate anus-spinal defect syndrome).

Low Abnormalities

Low abnormalities are common (40% of abnormalities) and include ectopic (perineal, vestibular, vulvar) anus. Fistulas may or may not be present; associated abnormalities are rare. The anus opens anterior to its normal position, sometimes in the vulva. The ectopic anorectum lies below the puborectalis muscle. In contrast, congenital rectovestibular or rectovaginal fistula opens into the vagina or the vulva but above the puborectalis muscle (40). In a related anomaly, the covered anus, a bar of skin derived from the lateral genital folds, covers the anal canal. An anocutaneous fistula passes anteriorly from the anal canal to the exterior at the perineal raphe. A misplaced external sphincter with conjoined fibers inserted behind the elongated, ventrally angulated terminal canal can functionally obstruct fecal passage even in patients with an adequate anal canal and anal orifice. These anomalies can generally be treated with relatively localized surgery with a good outcome.

Intermediate Abnormalities

Intermediate abnormalities are rare (15%) and include proximal anal canal stenoses. The terminal bowel appears dilated and thickened (41), and a shortened anal canal lies within the levator diaphragm. Other changes depend on the sex of the individual. In males, there is a clear separation between fibers running toward the pubis and others running toward the perineal body and bulbocavernosus muscle ventrally. Striated muscle fibers of the pubococcygeus muscle associate with the bowel wall. Fibers of the puborectalis may be present dorsally and laterally (42). Girls with a rectovestibular fistula lack the perineal body (central tendon) that normally lies between the rectum and vagina. Fascicles of the pubococcygeus and the external sphincter become displaced laterally.

High (Supralevator) Abnormalities

Supralevator anomalies account for 40% of anal abnormalities and include anorectal agenesis. Anorectal agenesis is a relatively primitive defect reflecting a cloaca that has not divided into separate urinary and alimentary canals. For this reason, the defect is also referred to as primitive cloaca, cloacal persistence, or rectocloacal fistula. The rectum reaches the upper surface of the pelvic floor, but the entire anal canal and pelvic floor musculature are absent. The rectum opens into a posterior urethra or bladder in males and into a posterior vaginal fornix in females. Failure of the müllerian systems to fuse normally creates two uteri that open into the globular cloacal cavity. Trisomy 4 is found in some patients (43). These abnormalities have a severe prognosis and more complicated surgical repair because of the obstruction and the common association with other congenital anomalies involving the vertebrae and urinary tract as well as defective innervation of the pelvic musculature. The musculature when it is examined may show hypoplasia of the muscularis propria, and there may be evidence of oligoneuronal hypoganglionosis or neuronal dysplasia.

Cloacal Exstrophy and the OEIS Complex

The OEIS syndrome is the most severe spectrum of birth defects involving the GI tract (and other sites). It affects 1 in

200,000 to 400,000 pregnancies and has an unknown cause. The male-to-female incidence is 3:1. The disease is usually sporadic in nature. However, it can affect siblings from separate pregnancies, suggesting that some cases may have a genetic basis (44). Some patients have trisomy 18; others may have prenatal exposures to methamphetamines or other recreational drugs or maternal heparin use (45).

200,000 to 400,000 pregnancies and has an unknown cause. The male-to-female incidence is 3:1. The disease is usually sporadic in nature. However, it can affect siblings from separate pregnancies, suggesting that some cases may have a genetic basis (44). Some patients have trisomy 18; others may have prenatal exposures to methamphetamines or other recreational drugs or maternal heparin use (45).

There is usually exstrophy of the urinary bladder and small or large intestines, anal atresia, colonic hypoplasia, omphalocele, and external genitalia anomalies (46). Other less frequent abnormalities include meningocele, spina bifida, unilateral hypoplasia of the kidney, single umbilical artery, Meckel diverticulum, and colonic duplication (47). The exstrophy–epispadias sequence includes, in increasing order of severity, phallic separation with epispadias, pubic diastasis, cloacal exstrophy, and the OEIS complex. Cloacal exstrophy is also a complex spectrum of malformations that is often fatal. In addition to an imperforate anus, the babies have an omphalocele, two exstrophic bladders between which there is an open cecum, and a blindly ending colon hanging down in the pelvis from the cecum (48).

Caudal Dysplasia (Caudal Regression Syndrome)

The caudal dysplasia syndrome associates with sacral vertebral anomalies, abnormalities in the pelvis and lower limbs, anal and genital defects, absent fibula, short femoral bones, and meningomyelocele (49). Heart anomalies and tracheoesophageal fistula may also be present. In its severest form, sirenomelia is present (50). The anal malformations include a complete covered anus with or without fistula formation and rectal atresia. Caudal regression syndrome associates with maternal diabetes or prediabetes (50). Other syndromes that closely resemble caudal dysplasia include the Aschcraft syndrome of familial hemisacrum (51) and the Cohn-Bay-Nielsen syndrome of familial hemisacrum (52).

Anorectal Cysts (Hindgut Cysts, Tailgut Cysts)

Some developmental cysts represent sequestered duplications; others represent a form of teratoma; still others are thought to arise from embryonic remnants of the tailgut or the neuroenteric canal (53,54) (Fig. 15.13). Early in development, the embryo possesses a true tail, which reaches its largest diameter at 35 days of gestation (8 mm). The anus develops above the tail on day 56 of gestation (35 mm), by which time the tail completely regresses (55,56). The neuroenteric canal, the connection between the amnion and the yolk sac, forms around day 16 and obliterates once the notochord forms. Remnants of this canal can give rise to presacral cysts (55).

Developmental cysts lie anterior to the coccyx or lower sacrum. Most cases are asymptomatic and found incidentally. They present as retrorectal or posterior anal masses in children and young adults, more commonly affect females than males, and often coexist with other congenital abnormalities, including spina bifida and stenosis. Although these lesions are congenital anomalies, they most commonly present in patients with an average age of 36 (55). Complications include infection, bleeding, or malignant degeneration.

The lesions usually appear multicystic and may measure many centimeters in diameter. Rarely, a unilocular cyst is present. The cysts do not communicate with one another, but are separated by a dense fibrous connective tissue stroma. Squamous, transitional, simple, mucinous, columnar, and/or ciliated columnar epithelia line the cystic spaces. The lumen may be filled with mucin or gelatinous material. The lesions also contain disorganized smooth muscle bundles. Anal developmental cysts differ from duplication cysts in that the musculature of duplication cysts appears much more orderly than the haphazard muscular orientation seen in anorectal developmental cysts. There is no evidence of dysplasia and no teratomatous elements are present. Benign retrorectal cystic teratomas should only be diagnosed when there is evidence of differentiation into all three germ cell layers (54).

In contrast to the cysts derived from tailgut remnants that are usually small and multilocular with satellite cysts, hindgut cysts resemble duplication cysts. They are larger, unilocular, and surrounded by a variably thick muscle layer (57).

They often contain heterotopic tissue such as pancreatic or gastric tissue. The cysts grow slowly and frequently remain asymptomatic unless they grow large enough to cause pressure, fullness, constipation, urinary and/or fecal incontinence, perineal pain, and/or numbness. Infected cysts may lead to retrorectal abscesses and fistula formation (52). Duplication cysts resemble duplication cysts described in Chapters 6 and 13. When they contain ectopic gastric mucosa, peptic ulcers may develop. The differential diagnosis includes anal duct cyst, hindgut cyst, and tailgut cyst.

They often contain heterotopic tissue such as pancreatic or gastric tissue. The cysts grow slowly and frequently remain asymptomatic unless they grow large enough to cause pressure, fullness, constipation, urinary and/or fecal incontinence, perineal pain, and/or numbness. Infected cysts may lead to retrorectal abscesses and fistula formation (52). Duplication cysts resemble duplication cysts described in Chapters 6 and 13. When they contain ectopic gastric mucosa, peptic ulcers may develop. The differential diagnosis includes anal duct cyst, hindgut cyst, and tailgut cyst.

Ectopic Tissues

Ectopic prostatic tissue in the anal submucosa (58,59) presents as a presacral mass or abnormal bowel movements, although this is rare (59). Grossly, the lesion may appear as a multiloculated cyst containing thick, milky tan-yellow fluid. Hyperplastic smooth muscle fibers and dilated prostatic glands arranged in a dense fibromuscular stroma are present. The epithelium demonstrates a range of morphologic appearances. Typical cuboidal prostatic glandular epithelium lines the majority of the glands. In many glands, the cells pile up into small papillae containing thin, fibrovascular cores. Glandular hyperplasia may be present. Focally, features of low-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia may be present (59). The epithelium is positive for prostate-specific antigen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree