Adequate bowel preparation is essential for optimal colonoscopy. Suboptimal bowel preparation occurs in 25% to 40% of cases and is associated with canceled procedures, prolonged procedure time, incomplete examination, increased cost, and missed pathology. There are several effective formulations for colon cleansing with a good safety profile. Split dosing should be implemented whenever possible in an effort to enhance tolerance and adherence, and improve mucosal visibility and overall quality of the examination. In this review, modern bowel preparations are discussed including their mechanism of action, mode of use, safety, and how to optimize outcomes.

Key points

- •

Adequate bowel preparation is essential for optimal performance of colonoscopy.

- •

There are several effective formulations with a good safety profile and these may be used interchangeably in patients without significant comorbidities depending on the patient profile and physician preference.

- •

Polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution is the preferred regimen in patients with cardiac, renal, or liver disease because of its limited effect on plasma volume and electrolyte homeostasis.

- •

Regardless of choice, split dosing is an important and established concept that should be implemented whenever possible in an effort to enhance tolerance and adherence, and improve mucosal visibility and overall quality of the examination.

- •

The burden of the preparation on patients including dietary modifications and disturbance of daily routine and sleep should be taken into consideration.

- •

Proper patient education regarding the different steps of the proposed preparation and the need for compliance and adherence are essential.

Introduction

Colonoscopy is the preferred procedure for investigating large-bowel and terminal ileal disease in adults and children. In addition, colonoscopy is the current gold standard for colorectal cancer screening because of its high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity and its unique capability to permit sampling and removal of polyps. For optimal performance and visualization of mucosal lesions and details, however, adequate bowel preparation is essential. This is of particular importance in the screening setting where the objective is identification and removal of all resectable polyps including flat lesions. Colonoscopy preparations are generally poorly tolerated, disliked and, consequently, serve as an impediment to colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Mounting evidence suggests that the fear of bowel preparation is a key reason many avoid colonoscopy. Patients who have undergone colonoscopy state that the bowel preparation was the worst part of the experience, and, as a result, are sometimes reluctant to undergo the procedure again or recommend it to others. In addition, patients commonly experience adverse events of the bowel preparation, including bloating, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which may lead to interruption or incomplete adherence. This may result in suboptimal bowel cleansing leading to incomplete examination, poor visualization of the mucosa, and missed colon pathology.

Adequate bowel preparation, defined by the ability to detect polyps 5 mm or larger, is crucial for the effectiveness of colonoscopy as a screening tool. This definition may be useful as a benchmark for screening examinations but in essence indicates the ability to achieve proper and complete mucosal inspection. Despite the unquestionable need for adequate colon cleansing, suboptimal bowel preparation occurs with surprising frequency in as many as 25% to 40% of cases. Inadequate bowel preparation is associated with canceled procedures, prolonged procedure time, incomplete examination, increased cost and possibly complications, physician frustration and patient anxiety, but most importantly, with missed pathology ( Table 1 ). The latter may be associated with the potential for medicolegal liability when an interval cancer is diagnosed before a timely repeat proper examination.

| Outcome | Low-Quality Preparation | High-Quality Preparation | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean time to cecum (min) | 16.1 | 11.9 | <.001 |

| Mean withdrawal time (min) | 11.3 | 9.8 | <.001 |

| Polyps of any size (%) | 23.9 | 29.4 | .007 |

| Polyps >10 mm detected (%) | 4.3 | 6.4 | .016 |

Some studies have suggested that suboptimal colon preparation significantly decreases the ability to detect colon polyps but not necessarily colon cancer. In a study by Harewood and colleagues, small colonic polyps (<9 mm) were more frequently detected during colonoscopies performed in patients with adequate bowel preparation than in those with inadequate preparation (22% vs 19%, respectively; P <.0001). However, larger polyps (>9 mm) were detected at the same rate (7%) irrespective of the quality of the preparation. Other studies reported high miss rates of adenomas and advanced lesions, as high as 34% to 42% and 18% to 27% respectively, when preparation for screening colonoscopy was unsatisfactory. A large European prospective observational multicenter study, involving 5832 patients, found that all polyps were more likely to be discovered in an adequately prepared colon than in an inadequately prepared colon. Furthermore, other important outcomes of colonoscopy were also found to significantly improve with higher cleansing quality ( Box 1 ). As mentioned earlier, suboptimal bowel preparation is associated not only with decreased adenoma detection rate but also with increased cost of colonoscopy by virtue of decreased interval to repeat examination. Therefore, efforts to improve the quality of bowel preparation are critical. In this review, the different colonoscopy preparation regimens are compared, and the modern bowel preparations and ways to optimize such an important variable are discussed.

Prolonged procedure time

Increased potential for missed pathology

Incomplete colonoscopy

Possible increased complications (eg, perforation of an inadequately prepared bowel)

Increased cost (decreased interval to repeat examination)

Potential for medicolegal liability (if timely repeat colonoscopy is not undertaken and an interval colon cancer is diagnosed within a short time period)

Introduction

Colonoscopy is the preferred procedure for investigating large-bowel and terminal ileal disease in adults and children. In addition, colonoscopy is the current gold standard for colorectal cancer screening because of its high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity and its unique capability to permit sampling and removal of polyps. For optimal performance and visualization of mucosal lesions and details, however, adequate bowel preparation is essential. This is of particular importance in the screening setting where the objective is identification and removal of all resectable polyps including flat lesions. Colonoscopy preparations are generally poorly tolerated, disliked and, consequently, serve as an impediment to colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Mounting evidence suggests that the fear of bowel preparation is a key reason many avoid colonoscopy. Patients who have undergone colonoscopy state that the bowel preparation was the worst part of the experience, and, as a result, are sometimes reluctant to undergo the procedure again or recommend it to others. In addition, patients commonly experience adverse events of the bowel preparation, including bloating, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which may lead to interruption or incomplete adherence. This may result in suboptimal bowel cleansing leading to incomplete examination, poor visualization of the mucosa, and missed colon pathology.

Adequate bowel preparation, defined by the ability to detect polyps 5 mm or larger, is crucial for the effectiveness of colonoscopy as a screening tool. This definition may be useful as a benchmark for screening examinations but in essence indicates the ability to achieve proper and complete mucosal inspection. Despite the unquestionable need for adequate colon cleansing, suboptimal bowel preparation occurs with surprising frequency in as many as 25% to 40% of cases. Inadequate bowel preparation is associated with canceled procedures, prolonged procedure time, incomplete examination, increased cost and possibly complications, physician frustration and patient anxiety, but most importantly, with missed pathology ( Table 1 ). The latter may be associated with the potential for medicolegal liability when an interval cancer is diagnosed before a timely repeat proper examination.

| Outcome | Low-Quality Preparation | High-Quality Preparation | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean time to cecum (min) | 16.1 | 11.9 | <.001 |

| Mean withdrawal time (min) | 11.3 | 9.8 | <.001 |

| Polyps of any size (%) | 23.9 | 29.4 | .007 |

| Polyps >10 mm detected (%) | 4.3 | 6.4 | .016 |

Some studies have suggested that suboptimal colon preparation significantly decreases the ability to detect colon polyps but not necessarily colon cancer. In a study by Harewood and colleagues, small colonic polyps (<9 mm) were more frequently detected during colonoscopies performed in patients with adequate bowel preparation than in those with inadequate preparation (22% vs 19%, respectively; P <.0001). However, larger polyps (>9 mm) were detected at the same rate (7%) irrespective of the quality of the preparation. Other studies reported high miss rates of adenomas and advanced lesions, as high as 34% to 42% and 18% to 27% respectively, when preparation for screening colonoscopy was unsatisfactory. A large European prospective observational multicenter study, involving 5832 patients, found that all polyps were more likely to be discovered in an adequately prepared colon than in an inadequately prepared colon. Furthermore, other important outcomes of colonoscopy were also found to significantly improve with higher cleansing quality ( Box 1 ). As mentioned earlier, suboptimal bowel preparation is associated not only with decreased adenoma detection rate but also with increased cost of colonoscopy by virtue of decreased interval to repeat examination. Therefore, efforts to improve the quality of bowel preparation are critical. In this review, the different colonoscopy preparation regimens are compared, and the modern bowel preparations and ways to optimize such an important variable are discussed.

Prolonged procedure time

Increased potential for missed pathology

Incomplete colonoscopy

Possible increased complications (eg, perforation of an inadequately prepared bowel)

Increased cost (decreased interval to repeat examination)

Potential for medicolegal liability (if timely repeat colonoscopy is not undertaken and an interval colon cancer is diagnosed within a short time period)

The ideal bowel preparation

The ideal bowel preparation should be simple to administer, palatable, well tolerated, and effective in adequately cleansing the colon without altering colonic mucosa or plasma fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. Moreover, it should be free of other significant adverse effects and have no important contraindications for use in special populations such as patients with heart, liver, or kidney disease, pregnant women, or children. Although bowel preparations are traditionally described in terms of the solution administered (eg, sodium sulfate, sodium phosphate [NaP], and so forth.), many additional elements are involved in the process ( Box 2 ). These include various dietary modifications and time of intake of the solution leading to important adjustments in the patient’s social and work schedule and affecting the immediate preprocedural quality of life, which often goes unregistered in clinical trials. When evaluating studies examining the efficacy of a certain preparation, these factors should be taken into consideration. Therefore, the ideal bowel preparation should be one that has the least impact on patients’ lifestyle. A one-type-cleans-all formulation does not exist at this stage and even the best regimen invariably fails in some patients. Customizing the preparation is sometimes necessary in particular situations such as in patients with severe constipation, those receiving psychotropic or anticholinergic drugs, and, intuitively, in patients with a history of inadequate bowel preparation at previous colonoscopy.

At scheduling: comprehend detailed explanation of the preparation including dietary restrictions using information leaflets, cartoons, and videos

Day −1: Trigger reminder of colonoscopy appointment and initiate dietary changes

Day −1: Adjust work and social schedule

Day −1: Expect to feel hungry and experience possible sleep disturbance

Day 0 ∗ : Restrict long-distance commute before procedure

Day 0: Ensure easy access to restrooms

∗ Day 0, day of colonoscopy.

Evolution of the bowel preparation

Colonoscopy preparations have evolved significantly over time. Early preparations were patient unfriendly, time consuming, and associated with fluid and electrolyte disturbances. In 1980, polyethylene glycol-electrolyte (PEG-E) solutions were introduced by Davis and colleagues and became the most commonly used purgatives for colonic cleansing. These are nonabsorbable isosmotic solutions and thus do not induce any substantial shifts in plasma fluid and electrolyte levels. Traditionally, 4 L PEG-E solutions were given 1 day before colonoscopy. Their main disadvantages were the large volume, poor palatability, and the need to adhere to dietary restrictions. This led to poor adherence prompting further modifications of the PEG-E solutions, such as fruit-flavoring and low-salt formulations, as well as the search for alternatives. NaP solutions were introduced in the late 1980s as a low-volume substitute for PEG-E, and were shown to result in effective colon cleansing when compared with conventional preparations. Subsequent reports of phosphate nephropathy led to development of other small volume non–phosphate-containing solutions based on sodium sulfate or sodium picosulfate with magnesium. Reduced volume PEG-E with ascorbic acid or adjuvant bisacodyl were similarly shown to be effective means of bowel cleansing with improved tolerance and adherence.

Assessment of quality of bowel preparation

In clinical practice, the quality of bowel preparation is naturally determined during colonoscopy. Studies have shown that patients’ own perception of the quality of the preparation is often inaccurate. Questions regarding the color and quality of the last fecal effluent may be helpful before examination. Patients who report poor adherence to the prescribed regimen and/or a turbid or brown last fecal effluent may be better rescheduled for another date using a different or modified preparation regimen. This preexamination assessment is probably money saving by avoiding the possibility of an aborted examination and the potential financial obligations of a repeat colonoscopy.

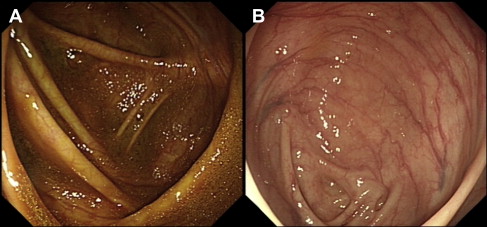

Clinical trials assessing the efficacy of modern bowel preparations have relied on several validated bowel preparation scales including the modified Aronchick scale, the Ottawa scale, and the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS). These scales vary in complexity from a relatively simple 5-point rating for the modified Aronchick scale (poor to excellent) based on residual stool and fluid consistency to the BBPS, which assesses each colonic segment separately including attention to residual mucosal staining, to the more complex Ottawa scale, which is a calculated numerical score (range 0–14 points) based on segmental presence or absence and quality of any residual fluid and the need for wash and suction. There are a limited number of studies evaluating the agreement or concordance between these scales but they could be complementary. Fig. 1 illustrates the potential for discrepancy between the aforementioned scales when significant residual mucosal staining in the absence of liquid or solid stools may not be specifically accounted for, or given enough weight, in 1 scale versus another. In addition, there is no standardization of whether a preparation should be scored during the insertion or the withdrawal phase of the examination. In clinical practice, however, the quality of preparation is often based on a global assessment by the performing endoscopist. Despite a relatively low likelihood of investigator bias, studies have shown fair to good interobserver and intraobserver agreement regarding the quality of bowel preparations. Thus, there seems to be a need for proper standardization of the quality of bowel preparation in future trials as well as in clinical practice.

Dietary modifications in bowel preparation

As discussed earlier, diet is a central and integral part of bowel preparation with important effects on the quality of the preparation as well as the immediate preprocedural quality of life of patients. A clear liquid diet was traditionally recommended before colonoscopy and influenced both patient compliance and resulting cleanliness of the bowel preparation. A clear liquid diet is recommended by most manufacturers starting at or before lunch the day before colonoscopy. This was challenged in several randomized controlled trials that showed that the efficacy of the bowel preparation was unaltered by low-residue diet using PEG-E, NaP, and magnesium citrate plus bisacodyl preparations. Although a low-residue diet is better tolerated than a liquid diet, the need to adhere to a low-residue diet remains an unwelcome burden for patients (see Box 1 ) and compliance is usually poor, particularly when recommended for 2 or 3 days before the scheduled colonoscopy. In our experience, patients rank dietary modifications and restrictions as an important negative aspect of the procedure, second only to the volume and taste of the preparation. A randomized controlled trial by Aoun and colleagues showed that an unrestricted diet and split-dose PEG-E was superior to 4 L PEG-E with a liquid diet. The validity of this strategy was confirmed in a recent trial showing good or excellent colon cleansing in 86 of 99 patients (87%) receiving a regular unrestricted diet for breakfast and lunch, a full liquid dinner and 4 L split-dose PEG-E.

Modern bowel preparations

PEG-E

PEG-based solutions consist of a high-molecular-weight nonabsorbable polymer in a dilute electrolyte solution. PEG-E solutions are designed to be osmotically balanced, limiting the exchange of fluid and electrolytes across the colonic membrane. A variety of PEG-E preparations are currently available for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy. These differ with respect to volume, electrolyte content, molecular weight of the polymer, artificial flavorings, and the presence of artificial sweeteners. Sulfate-free PEG-E is less salty, more palatable, but comparable with PEG-E in terms of effective colonic cleansing and overall patient tolerance. Traditionally, 4 L of PEG-E were used 1 day before colonoscopy. The recommended dosing of most PEG-E is 240 mL every 10 min until completion or a persistently clear rectal effluent. It is estimated, however, that 5% to 15% of patients are unable to consume the full dose of PEG-E because of palatability and/or adverse effects including bloating, nausea, and vomiting. The timing of PEG-E doses and its relationship to the time of colonoscopy has proved to be important both for tolerability of patients and the quality of the bowel preparation. PEG-E taken in divided or split doses (2 L the evening before and 2 L the morning of the procedure) was demonstrated in multiple randomized trials to be better tolerated and more effective than the standard 4-L dose given 1 day before, with good or excellent preparation achieved in 80% to 90% of patients. The improved outcome with split dosing led to testing and development of split-dose low-volume PEG-E formulations containing ascorbic acid or supplemented with adjuvant bisacodyl. Randomized controlled trials showed that these lower volume formulations were equivalent to standard 4 L PEG-E, and even split-dose PEG-E, and were generally associated with less side effects.

Two recent meta-analyses have demonstrated that split-dose PEG-E results in much higher rates of adequate bowel preparation than the standard full-dose regimen, partly because of fewer discontinuations and lower incidence of nausea but perhaps, more importantly, because of the timing of the final dose in relation to the colonoscopy (discussed later). In their meta-analysis, Enestvedt and colleagues showed that 4 L split-dose PEG-E is superior to other bowel preparation comparators for bowel cleansing (including split dose of either 2 L PEG-E + ascorbic acid, NaP, or MiraLAX/Gatorade) and suggested that it be considered the standard against which new bowel preparations are compared.

Reduced-Volume PEG-E + Ascorbic Acid

PEG–E plus ascorbic acid and sodium sulfate is a low-volume PEG-based formulation. The megadose of ascorbic acid used is not completely absorbed, remaining in the colonic lumen, where it exerts an osmotic effect thereby reducing the necessary effective volume of colon cleansing solution to 2 L. Each liter of PEG-E + ascorbic acid contains 100 g macrogol 3350, 7.5 g sodium sulfate, 2.7 g sodium chloride, 1 g potassium chloride, 4.7 g ascorbic acid, 5.9 g sodium ascorbate, and lemon flavoring. Patients scheduled for a morning colonoscopy are instructed to take the 2 L preparation in the afternoon and evening the day before the colonoscopy. Those scheduled in the afternoon take 1 L the evening before and 1 L early in the morning on the day of colonoscopy. With every liter of PEG-E + ascorbic acid, patients should also take at least half a liter of a clear fluid to avoid dehydration. The efficacy of 2 L PEG-E + ascorbic acid was evaluated in several randomized controlled trials. Coporaal and colleagues compared 2 L PEG-E + ascorbic acid with 4 L split-dose PEG-E and found that both preparations were equally effective. These results are in line with those from Ell and colleagues who demonstrated successful bowel cleansing in 88.9% of patients receiving PEG-E + ascorbic acid versus 94.8% of patients prepared with PEG-E. Similarly, compared with NaP, PEG-E + ascorbic acid provided successful bowel cleansing in 72.5% of cases versus 63.9% with NaP. PEG-E + ascorbic acid has also been investigated versus sodium picosulfate + magnesium citrate. Again, both preparations produced similar success rates of 84.4% with PEG-E + ascorbic acid and 72.7% with sodium picosulfate + magnesium citrate.

NaP

NaP preparations are available in aqueous and tablet forms. Several randomized controlled trials have compared NaP and standard 4 L PEG-E suggesting they are equally effective with better tolerance and acceptability of NaP. A meta-analysis by Tan and Tjandra concluded that NaP was more effective in bowel cleansing than standard PEG-E or sodium picosulfate and comparable in terms of adverse events. A recent large prospective randomized trial by Lawrance and colleagues comparing NaP, PEG-E, and sodium picosulfate preparations showed that NaP gave the worst results for morning procedures, whereas all 3 preparations were similarly effective for afternoon procedures. Most studies comparing NaP with PEG-E did so against standard 4 L PEG-E administered the day before colonoscopy. A randomized trial by Seo and colleagues compared head-to-head NaP with split-dose PEG-E without strict dietary restrictions and showed no significant difference in efficacy between the 2 preparations. Split-dose PEG-E was, however, associated with significantly less nausea and vomiting. The dose of aqueous NaP is 45 mL taken in divided doses, 10 to 12 hours apart with 1 of the doses taken on the morning of the procedure. Proper hydration and consumption of clear fluids and water is recommended. A particular concern with the use of NaP is the potential risk of acute phosphate nephropathy (discussed later).

The tablet form of NaP was designed to improve taste and limit the volume of liquid required. The recommended dosage is 32 to 40 tablets taken as 20 tablets the evening before and 12 to 20 tablets the day of the procedure (3–5 hours earlier). The 20 tablets are taken as 4 tablets every 15 minutes with 240 mL of clear liquid. Each 2 g tablet contains 1500 mg of active ingredients (monobasic and dibasic NaP) and 460 mg of microcrystalline cellulose as a tablet binder. The latter is a nonabsorbable inert polymer and remains insoluble in the gastrointestinal tract. Initially, 2 large multicenter randomized controlled trials compared NaP tablets with conventional 4 L PEG-E regimens and found that they were equally effective in terms of colon cleansing. The quality of the bowel preparation was excellent or good in 84.3% of patients in the NaP tablet group and in 76.7% in the PEG-E group. Patient compliance was greater in the tablet group, and there were significantly fewer gastrointestinal side effects in this group. However, the use of NaP tablets has some shortcomings in that the inactive microcrystalline cellulose ingredient produces a residue that obscures the mucosal surface and a large number of tablets need to be ingested over a short period of time. These drawbacks have been partly addressed by reducing the amount of microcrystalline cellulose per tablet as well as the number of NaP tablets to be ingested from 32 to 28 to improve compliance and tolerability.

Oral Sodium Sulfate

An oral sodium sulfate (OSS)-based solution was developed as a new low-volume alternative to NaP. This solution does not contain phosphate and is therefore unlikely to cause phosphate nephropathy. Only 2 randomized trials have been published to date comparing OSS with 2 L PEG-E + ascorbic acid or with standard 4 L PEG-E. OSS was found to be superior to 4 L PEG-E, equally effective as 2 L PEG-E + ascorbic acid, and to have an acceptable safety profile. The preparation (consisting of 17.5 g sodium sulfate, 3.13 g potassium sulfate, and 1.6 g magnesium sulfate in each 1.8 L bottle) is used in split doses; each bottle is administered as 480 mL of diluted solution with an additional 1 L of water. A light breakfast only and/or clear fluids are recommended the day before the procedure.

Sodium Picosulfate/Magnesium Oxide/Citric Acid Preparations

Sodium picosulfate combined with magnesium citrate (P/MC) acts locally in the colon as both stimulant and osmotic laxative. Sodium picosulfate is a prodrug hydrolyzed by bacteria in the colon into its active metabolite, which acts as a stimulant laxative causing transfer of fluid and electrolytes to the bowel lumen. It is used commercially with magnesium oxide and citric acid to improve taste and cathartic effect. P/MC has better tolerability and acceptability than PEG-E or NaP. Similar to all aforementioned regimens, using P/MC in a split-dose regimen was shown to be superior to the traditional dosing regimen for bowel preparation for colonoscopy. More recently, a large randomized multicenter assessor-blinded study of day-before split-dose P/MC versus 2 L PEG-E + bisacodyl was published. P/MC provided superior overall colon cleansing compared with day-before PEG-E + bisacodyl (84.2% vs 74.4%), as well as in each segment of the colon. The instructions are as follows: 2 sachets of P/MC are reconstituted in 150 mL of water each and taken as split doses, 1 day before colonoscopy, starting between 4 and 6 pm with the second dose taken after 6 hours, but no later than 9 hours before the procedure. On the day before the procedure, all patients were limited to a clear liquid diet. Despite its small volume and good acceptance and palatability, the burden of this particular preparation regimen on the individual daily schedule and sleep may be more substantial than other preparations given its relatively delayed onset of action, the time difference between doses (the second dose was taken after 10 pm ), and the need for continued proper hydration with clear fluids throughout the preparation period. A true split-dosing regimen on consecutive days may be friendlier, with the second dose taken 4 hours before the examination, but would be useful mostly in patients scheduled for late morning or afternoon colonoscopy. Oral P/MC is generally well tolerated. Adverse events are primarily gastrointestinal in nature and usually mild to moderate in intensity.

MiraLAX/Gatorade Combination

MiraLAX (PEG 3350) (Schering-Plough Healthcare Products, Inc, Kenilworth, NJ) is a laxative approved for the treatment of mild or occasional constipation. When used as a laxative, MiraLAX can cause excessive volume depletion and is not recommended in patients with kidney disease. Furthermore, it carries an even greater risk of volume depletion and potential electrolyte disturbances when taken as a bowel preparation at a dose 14 times (238 g) higher than the recommended laxative dose. MiraLAX does not contain a built-in electrolyte replacement solution, so the diarrhea it induces correlates with volume depletion and electrolyte imbalance. In an attempt to limit this problem, MiraLAX is often administered in combination with a hydrating sports drink (eg, Gatorade; PepsiCo, Purchase, NY) to boost electrolytes. Hjelkrem and colleagues found that split-dose MiraLAX in 2 L of Gatorade is not as effective as 4 L split-dose PEG-E in bowel cleansing. This finding was corroborated by another trial by Enestvedt and colleagues. However, MiraLAX/Gatorade was better tolerated in both studies. A prospective randomized controlled study evaluating the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of whole-dose and split-dose regimens of MiraLAX/Gatorade versus PEG-E found that split-dose MiraLAX/Gatorade and split-dose PEG-E were more effective than whole-dose PEG-E. MiraLAX/Gatorade was preferred over PEG-E by the study participants. Bowel preparation with MiraLAX/Gatorade did not lead to any clinically significant electrolyte changes or clinically adverse event in any of the low-risk patients in this study. The combination of MiraLAX/Gatorade is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for bowel cleaning before colonoscopy.

Timing of administration of the bowel preparation

The timing of bowel preparation in relation to endoscopy is an increasingly important consideration. Church compared full-volume PEG-E taken on the morning of an afternoon colonoscopy with the same preparation taken the day before, showing that the quality of bowel preparation was significantly better with the shorter time interval. The concept of split dosing was introduced in an attempt to refine bowel preparation by improving tolerance and adherence to 4 L PEG-E and to allow next-day examination of patients when required. Dose splitting (2 L the evening before and 2 L the morning of the procedure) was found to be superior to the conventional 4 L day-before preparation, in terms of quality and tolerability of the preparation, and obviated the need for significant dietary restriction. Multiple randomized trials and meta-analyses have subsequently demonstrated that a split-dosing regimen, irrespective of the bowel preparation used, is more effective than its full-dose counterpart, partly because of less preparation discontinuations and lower incidence of nausea. Improved visualization of the right colonic mucosa was perhaps the biggest advantage of split-dose preparations. In patients who take the last purgative dose 8 to 12 hours before colonoscopy, new small bowel effluent accumulates in the right colon staining the mucosa and making visualization of mucosal details difficult (see Fig. 1 ). One study showed that split-dose NaP resulted in better bowel cleansing and significantly lower fecal material in the right colon compared with the full dose taken the day before (4% vs 30%). The bowel fluid was more translucent in the split-dosing group and more opaque in the day-before group. Parra-Blanco and colleagues compared the cleansing quality of PEG-E and NaP with different schedules of administration. Patients receiving the preparation on the same day as the colonoscopy were significantly more likely to have good or excellent global cleansing scores than those receiving day-before preparations. Flat lesions, but not flat adenomas, were also more frequent in patients prepared on the same day. These data suggest that the timing of the second dose in relation to the procedure is more important than the time between the first and second doses. Studies have confirmed that consumption of PEG-E less than 5 hours before the procedure is associated with the highest scores for bowel cleansing. Same-day bowel cleansing with all the solution consumed on the day of examination was recently shown to be superior to a split-dose PM/AM regimen but is arguably impractical except for afternoon procedures or in controlled settings.

Two theoretic barriers to the preferential use of split-dose regimens have been raised. The first is the concern about risk of sedation or anesthesia in patients consuming fluids close to procedure time. However, studies have shown that minimal fluid (≤20 mL) remains in the stomach 90 minutes after ingestion of 200 mL of water or full-fat milk or in patients undergoing concomitant esophagogastroduodenoscopy as early as 90 minutes after a last dose of PEG-E. The American Society of Anesthesia guidelines recommend that patients should fast for a minimum of 2 hours after consuming clear liquids before the administration of sedation. The second point of contention is that patients are not willing to wake up earlier on the day of colonoscopy for the second purgative dose. A survey conducted in 2008 revealed that 83% of patients would be willing to wake up as early as 3 am to take the second dose. In a comparative study, a significantly higher percentage of the split-dose group reported no or minimal difficulty completing the bowel preparation compared with the single-dose group (81% vs 55% respectively). In addition, significantly more patients in the split dose regimen were satisfied with the bowel preparation compared with the single-dose group (63% vs 46%, respectively). There was also no significant difference in the percentage of patients who stopped for a bowel movement on their way to colonoscopy. When asked which regimen was more convenient and less difficult to complete, 19% of patients in the pm / am split-dosing group versus 44% in the single-dose group found that the regimen was hard to complete.

The data suggest that patients accept a split-dosing regimen better, are able to complete the preparation with no or minimal difficulty, and are willing to wake up early if convinced the timing of the second dose will enhance the outcome of their colonoscopy. An increase in patient compliance with the preparation, and hence improved mucosal visualization, may lead to enhanced polyp detection, greater patient satisfaction and uptake of colonoscopy, as well as potential cost savings. Split dosing, where at least half of the preparation is given on the day of colonoscopy, is recommended in the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree