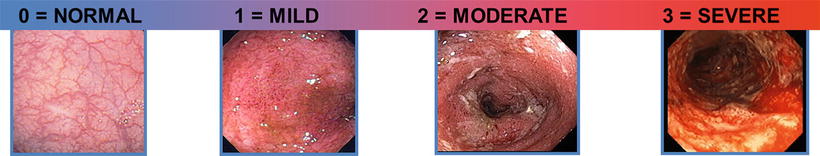

Fig. 5.1

Variable appearances of mucosa in ulcerative colitis

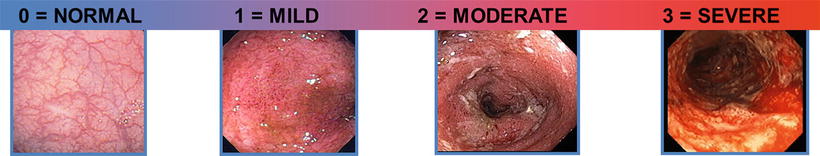

In an effort to quantify the degree of inflammation, a number of different clinical, endoscopic, and composite scoring systems have been developed over time (Table 5.1). Most frequently embraced is the so-called Mayo endoscopic subscore, which was developed from the previously published “Baron score” and modified in order to be part of a composite index (the “Mayo score”) for the clinical trials of delayed-release mesalamine [1]. In the Mayo endoscopic subscore, the endoscopic appearance is rated from 0 to 3 (Fig. 5.2). A score of 0 is termed “normal,” which is defined as an intact mucosa with a preserved vascular pattern and no friability or granularity. A score of 1 represents an abnormal appearance but is not grossly hemorrhagic. The mucosa may appear erythematous and edematous, and the vascular pattern may appear blunted. A score of 2 is moderately hemorrhagic, with bleeding to light touch but without spontaneous bleeding seen ahead of the instrument on initial inspection. In the traditional Mayo scoring, friability is part of a score of 1, but in the modified Mayo scoring (as in the clinical trials with MMX mesalamine), friability is part of a score of 2. A score of 3 is termed “severe,” which is defined as having marked erythema, absent vascular markings, granularity, spontaneous bleeding, and ulcerations. In most clinical trials, the term “mucosal healing” has been defined as a Mayo subscore of 0 or 1. The prior definitions of mucosal healing have had limitations, and there has been interest in clarifying endoscopic and histologic definitions for future clinical trials and disease management paradigms. Therefore, in 2007, the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IOIBD) defined mucosal healing as an absence of friability, blood, erosions, or ulcerations [2, 3].

Table 5.1

Measuring disease activity in ulcerative colitis

Based on clinical and biochemical disease activity | Based on endoscopic disease activity | Composite clinical and endoscopic disease activity |

|---|---|---|

Truelove and Witts severity index (TWSI) | Truelove and Witts sigmoidoscopic assessment | Mayo score (DAI) |

Powell-Tuck index | Baron score | Sutherland index (DAI, UCDAI) |

Clinical activity index (CAI) | Powell-Tuck sigmoidoscopic assessment | |

Activity index (AI or Seo index) | Rachmilewitz endoscopic index | |

Physician global assessment | Sigmoidoscopic index | |

Lichtiger index (mTWSI) | Sigmoidoscopic inflammation grade score | |

Investigators global evaluation | Mayo score flexible proctosigmoidoscopy assessment | |

Simple clinical colitis activity index (SCCAI) | Sutherland mucosal appearance assessment | |

Improvement based on individual symptom scores | Modified Baron score | |

Ulcerative colitis clinical score (UCCS) | UC endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) | |

Patient-defined remission |

Fig. 5.2

Representative photos of the Mayo endoscopic subscore. Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987 Dec 24;317(26):1625–9 [46]

Most recently, Travis and colleagues have described a novel UC scoring index of severity, the UCEIS (Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity). In the two-phase development study, a library of 670 video sigmoidoscopies from patients with composite Mayo scores between 0 and 11 were supplemented by 10 videos from 5 people without UC and 5 patients hospitalized with severely active disease. In phase 1, 10 investigators each viewed 16/24 videos to determine agreement on the Baron score with a central reader and agreed definitions of 10 endoscopic descriptors. In phase 2, 30 investigators each rated 25/60 videos for said descriptors and assessed overall severity on an analog scale that ranged from 0 to 100. The study found a 76 % agreement for severe and a 27 % agreement for normal endoscopic appearances. It was concluded that the UCEIS accurately predicted the overall assessment of endoscopic severity in UC; however, additional testing and further validity are needed before use in clinical practice.

For clinical trials, the use of a centralized reader for endoscopic scoring is of interest and has demonstrated significant impact on clinical trial outcomes. Further training of gastroenterologists in particular will be necessary in order to develop reliable approaches to the use of endoscopic mucosal healing as a clinical practice treatment endpoint [4, 5].

Histologic scoring of mucosal healing in UC notably, histologic findings previously have not been part of these definitions of mucosal healing in UC. The IOIBD also defined the two histologic patterns that are consistent with remission. The first is demonstration of chronic inflammation in the lamina propria with regular or irregular glands. The second is a lack of inflammation with an atrophic glandular pattern with short crypts, glands with lateral buddings, dichotomic glands, or an apparently normal glandular pattern [3]. Numerous methods of classifying histologic activity have been proposed, but despite emerging interest by regulatory bodies, these scales have not been validated as clinical trial endpoints or for clinical practice [6]. There remain numerous unanswered questions about whether histologic healing or remission can be a realistic treatment goal for the majority of patients [6, 7].

Why Mucosal Healing Is Important in UC

Although the obvious connection between the status of the mucosal inflammation and the condition of the patient with UC has long been recognized, it has only been in recent years that a therapeutic goal of mucosal healing could be entertained. This is due to the ability to measure mucosal injury in easier ways, emerging data on clinical outcomes associated with degrees of mucosal inflammation, and the development of many therapies that offer methods of healing the mucosa in patients with UC [2]. It is also due to the appreciation that symptoms similar to active UC can be mimicked by the presence of irritable bowel syndrome or, possibly, injury to the mucosa and submucosa from prior inflammation and chronic changes that occur. In addition, the emerging clinical goal of endoscopic mucosal healing enables further distinction from other conditions such as infections, which also may produce confounding symptoms. Therefore, the adoption of mucosal healing as a therapeutic goal theoretically can reduce the diagnostic reliance on subjective clinical characteristics. Such a therapeutic endpoint also clarifies response to therapy, so that therapeutic adjustments are made with more accurate information. Finally, emerging evidence demonstrates that endoscopic mucosal healing is associated with improved short- and long-term outcomes in UC (Table 5.2).

Table 5.2

Possible primary and secondary benefits of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis

Reduction of clinical relapse |

Reduction in surgical rates |

Reduction in hospitalization |

Reduction in neoplasia |

Improvement in quality of life |

Histologic and endoscopic inflammatory activity has been shown to be associated with higher rates of disease relapse in UC. Riley and colleagues evaluated 82 ulcerative colitis patients who were in remission to see if histologic inflammation during remission predicted relapse. Each of the 82 patients were in clinical remission and had rectal biopsies obtained at the beginning of the trial. They were then maintained on sulfasalazine or mesalamine and followed for clinical relapse. The investigators found that a number of histologic findings predicted clinical relapse. The histologic findings predictive of clinical relapse at 12 months were acute inflammatory cell infiltrate, crypt abscesses, mucin depletion, and breached surface epithelium [8]. A more recent study by Meucci and colleagues determined that endoscopic mucosal inflammation during clinical remission predicted disease relapse. The investigators induced clinical remission in ulcerative colitis patients with mesalazine and then performed colonoscopy at 6 weeks of treatment. Patients who had achieved both endoscopic and clinical remission by week 6 had a significantly lower rate of disease relapse in the following 12 months (23 %) than patients who achieved clinical remission alone (80 %, p < 0.01) [9].

Active endoscopic inflammation and mucosal healing are also predictive of rates of surgery. Carbonnel and colleagues performed endoscopy on 85 patients with active UC. They found that 93 % of patients with endoscopically severe disease (defined as deep/extensive ulcers, mucosal detachment, large mucosal abrasions, or well-like ulcers) required subsequent colectomy compared to 23 % of the patients with endoscopically moderately active disease (superficial ulcers, deep but not extensive ulcers) [10]. Additional evidence was described by Frøslie and colleagues in the study of a Norwegian observational cohort. Patients were enrolled and had follow-up colonoscopies 1 and 5 years after enrollment. Of the 354 patients who completed the follow-up, those who had achieved mucosal healing after the 1-year colonoscopy were less likely to undergo colectomy by the 5-year follow-up, regardless of treatment exposure (in other words, the healing itself was predictive of the outcome, not how they achieved it). The relative risk of having a colectomy in the patients with mucosal healing was 0.22 (95 % CI: 0.06–0.79) [11].

Increased histologic inflammatory activity is also associated with a higher risk of cancer and dysplasia. Rutter and colleagues first published a case-control study to evaluate the association between severity of inflammation on surveillance colonoscopy and later development of colonic dysplasia. Univariate analysis demonstrated that both endoscopic and histologic inflammation were associated with an increased risk for dysplasia and colorectal cancer. After controlling for other explanatory variables, only histologic inflammation was significantly associated with an increased risk for dysplasia or colorectal cancer. For each one-unit increase in the histologic score, the odds of colorectal neoplasia increased by a factor of 4.69 (95 % CI: 2.10–10.48, p < 0.001) [12]. Gupta and colleagues also reviewed a cohort of 418 patients and assessed their histologic activity scores, as reported by their pathologists. Univariate analysis found that mean, maximal, and cumulative severity of histologic inflammation was associated with significant risk for developing advanced neoplasia [13]. Rubin and colleagues performed a case-control study with 59 cases of colorectal neoplasia matched to 141 controls, with prospective regrading of the degrees of histologic inflammation by two expert pathologists. We created a novel expanded histologic grading scale, in order to capture more detail at the lower end of the scale, and included “normalization” of biopsies as well. On multivariate analysis, mean histologic activity index score over the surveillance period was significantly associated with colorectal neoplasia risk (as was male sex). For each one-unit increase in histologic activity index score, there was an adjusted odds ratio of 3.68 (95 % CI, 1.69–7.98; p = 0.001) [14]. These studies all demonstrate that increased inflammation over time is a specific and independent risk factor for neoplasia in UC. However, while these studies suggest that altering the course of inflammation may change the likelihood of cancer, there is no direct evidence of this point, and prospective studies to measure such an endpoint will be difficult to perform. Nonetheless, the British Society of Gastroenterology has incorporated a stratification scheme for intervals of surveillance colonoscopy based on the presence of inflammation during the exam [15].

Achieving Mucosal Healing with Therapy in UC

There are multiple therapeutic avenues by which to achieve mucosal healing in UC. The available therapies for UC include corticosteroids, 5-aminosalicylic acid derivatives, immunomodulators, and biological agents.

Interestingly, corticosteroids have been shown to have some mucosal healing effect for decades. In 1955, Truelove and Witts reported on the use of cortisone in UC. They identified a significant difference between the group treated with oral cortisone and the placebo group, with treated patients having a higher likelihood of achieving a normal or near-normal appearing bowel on sigmoidoscopy [16]. In a later report, they found similar results with intravenous steroids on inducing clinical remission but they did not report on sigmoidoscopic appearance [17]. More recent studies of oral glucocorticoids include a study by Lofberg and colleagues which compared oral budesonide and prednisolone. They used the Mayo endoscopic subscore to determine mucosal response to therapy. They found that 12 % of patients on budesonide and 17 % of patients on prednisolone achieved complete endoscopic remission and there was no significant difference between the two groups [18]. These findings must be interpreted with the additional knowledge that steroids are not effective maintenance therapies in UC and the understanding of the mechanism of steroids on the mucosa of UC, including the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, which may in fact impair healing.

Many studies have shown that 5-aminosalicylate therapy can achieve mucosal healing in UC and the majority have used the prior definition of a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 or 1. Kamm and colleagues studied mesalazine with Multi Matrix System (MMX) technology (Cosmo, Lainate, Italy) in patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis. They determined that 77.6 % of patients on 4.8 g of MMX mesalazine daily, 69.0 % of patients on 2.4 g of MMX mesalazine daily, and 61.6 % of patients on 2.4 g delayed-release mesalamine three times daily were able to achieve mucosal healing at 8 weeks of treatment. This was compared to 46.5 % of patients on placebo, and mucosal healing was defined as a modified Sutherland index less than or equal to 1 [19]. A similar study by Lichtenstein and colleagues studied the percentage of patients who received clinical and endoscopic remission in 8 weeks on MMX mesalamine at a dose of 2.4 g twice per day (n = 93), 4.8 g once per day (n = 94), or placebo (n = 93). This study reported similar results with remission achieved by 34.1 % of patients on a twice-daily dose of MMX mesalamine 2.4 g, 29.2 % on 4.8 g once daily, and 12.9 % on placebo [20]. The combined rate of mucosal healing in both of these studies was 32.0 % of patients on MMX mesalazine 2.4 g daily and 32.2 % of patients on MMX mesalazine 4.8 g daily, compared 15.8 % of patients in the placebo group [21].

In the ASCEND I study, Hanauer and colleagues reported that oral delayed-release mesalamine induced complete remission in 46 % and 36 % of patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis for 4.8 g daily and 2.4 g daily, respectively [22]. The ASCEND II study again compared delayed-release mesalamine in 4.8 g daily or 2.4 g daily formulations, limited to patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. The study found that 20.2 % of the patients on 4.8 g daily and 17.7 % of the patients on 2.4 g daily were able to achieve complete remission [23]. These studies reported patients who achieved complete remission, which required both endoscopic and clinical remission, but did not report on the subset that achieved mucosal healing. A combined analysis of patients with moderate ulcerative colitis from ASCEND I and ASCEND II showed mucosal healing (a score of 0 or 1) at week 3 in 65 % of patients receiving 4.8 g daily of delayed-release mesalazine and 58 % of patients receiving 2.4 g daily. At week 6 they found that mucosal healing rates were significantly higher in patients receiving 4.8 g daily than 2.4 g daily (80 % vs. 68 %, p = 0.012) [24]. In a subsequent post hoc analysis, Lichtenstein and colleagues reviewed the mucosal healing rates of the ASCEND trials when a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 was used and found that the healing rates were substantially lower in those treated with delayed-release mesalamine 2.4 g per day versus 4.8 g/day [24].

In another report, Kruis and colleagues studied once-daily dosing of mesalazine versus three times daily dosing in patients with ulcerative colitis [25]. In this study they measured mucosal healing by a Rachmilewitz endoscopic index of less than 4. Patients achieved mucosal healing in 71 % with once-daily dosing of mesalazine and 70 % of patients with three times daily dosing. These studies show that 5-ASA compounds, despite their different formulations, are capable of inducing mucosal healing (albeit with variable definitions) at significant rates for mild to moderate ulcerative colitis.

There is much less evidence regarding the immunomodulators, azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Ardizzone and colleagues compared the efficacy of azathioprine to oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for inducing remission in steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. They found that 53 % of patients taking azathioprine achieved both clinical and endoscopic remission compared to 19 % of patients taking oral 5-aminosalicylic acid (p = 0.006). Additionally, they found that the mean Baron index score for endoscopic activity was significantly lower in the azathioprine group compared to the 5-aminosalicylic acid group at the 3- and 6-month follow-up [26]. Paoluzi and colleagues also performed a trial of azathioprine without a comparison group. They found that 68.7 % of patients achieved endoscopic remission as defined by a Baron index score of 0 [27]. These studies suggest that mucosal healing is achievable with azathioprine, but the results are not directly comparable to other therapies and the exact rate of healing is not known.

The clinical trials of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors have shown that they are capable of inducing mucosal healing (Table 5.3). In contrast to the varied definitions of mucosal healing that studies of the other classes have used, the biologic therapy trials used a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 or 1 to define mucosal healing. Infliximab was found in the ACT 1 and ACT 2 trials to achieve mucosal healing at week 8 at rates of 16.5 % on adalimumab versus 9.3 % on placebo. Among those who were anti-TNF-α naïve compared to those who had previously received anti-TNF agents, the rates of remission at week 8 were 21.3 % on adalimumab and 11 % on placebo, and 9.2 % on adalimumab and 6.9 % on placebo, respectively. The significant difference between infliximab dosed at 5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, and placebo was also demonstrated at weeks 30 and 54 [28]. In a follow-up post hoc analysis, Colombel and colleagues showed that achieving Mayo endoscopy score of 0 or 1 was associated with a reduction in colectomy [29].

Table 5.3

Mucosal healing rates from trials of biologic therapies for ulcerative colitis

Drug | Clinical trial | Reported rates of mucosal healinga | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Infliximab | ACT1 | 5 mg | 10 mg | Placebo | |

8 weeks | 62.00 % | 59.00 % | 33.90 % | ||

p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

30 weeks | 50.40 % | 49.20 % | 24.80 % | ||

p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

54 weeks | 45.50 % | 46.70 % | 18.20 % | ||

p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

ACT2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |||||