Fig. 1.1

An appointment confirmation notice with a map can be extremely helpful to patients

Choosing a staff member for telephone scheduling and counseling is no trivial matter. A person who is rude, abrupt, or slow will have an outsized impact on your patient’s experience. Consider splitting the task between several people; the receptionist’s job is repetitive and tiring, and it is helpful to find ways to relieve stress and burnout. Maintaining a caring and friendly attitude is in everyone’s interest. Whatever attitude the patient is greeted with, or whatever frustrations they harbor from the obstacles they had to surmount to get to you, will be present when you begin your evaluation.

Referring doctors handle their patients’ referrals in different ways. Some will have the patient call and make an appointment without providing any information. Others will give the patient background records and studies to pass on, and some may even send a cover letter requesting the referral with records and studies included. Sometimes, a referring physician may be the first person to call regarding the patient and his problem. To aid the referring physician, the recording that usually greets him or her must be short and include the option to go quickly to a “live person” who can put him or her in contact with the surgeon. Listening to a long and time-consuming recorded message can lead to a hang-up and the loss of a referral. In recent years, we have maintained a separate telephone line, the “back line”, for physicians. It is provided to referring physicians who call frequently. The referring doctors message needs to be conveyed to the surgeon whether he or she is in the office or the operating room. A good experience for referring physicians makes it more likely they will call again. If the surgeon cannot be reached, staff should arrange an appointment for the patient and promise that the surgeon will be alerted so that a return call can be made.

(AS Kumar) I am in contact with many of my referring physicians by e-mail. Through my hospital’s secure network, they are able to send me the patient’s pertinent medical records as PDF attachments, and I am able to ask them the necessary questions to ascertain the urgency of the appointment. Often, especially if I get a sense that the patient will need minor surgery (e.g., a recent finding of anal dysplasia), I appreciate having control over my clinical schedule to get them triaged in time for an open, convenient slot in my operating room schedule. My referring providers appreciate how rapidly I get the issue settled. They enjoy knowing that the loop is closed. Often, the e-mail interaction with the referring physician is simply a quick reply that is forwarded to my front desk staff to schedule the appointment. On occasion, my front desk staff has been willing to e-mail the patient for additional information. Some practices rely almost exclusively on new patient referral requests coming through the Internet and hire staff specifically with this intent.

We look at the appointment schedule to review new patients and their diagnoses. We grew accustomed to doing so in residency when preparing for an upcoming clinic or a case. If we see that a neoplasm or pain is involved and the appointment seems to be too far in the future, we either alert a nurse to get more information or telephone the patient ourselves to hear an abbreviated history. At that time, we can reassert the need to bring the appropriate records and decide if it is best to move the appointment up, or delay it for completion of studies that may have been ordered by the referring physician, or that we think to order. A simple call creates an early bond that reassures the patient that you have their interest at heart and that communication lines between patient, the referring physician, and you are wide open. In addition, word of this call may be transmitted to the referring doctor, who will be appreciative of your efforts.

The Initial Encounter

Key concept: Oftentimes, the first impression is your best chance for a good impression—remember your appearance, demeanor, communication, and your organization have a major impact on how you are judged by your patients.

The second chance to be judged by the patient is upon arrival in the office. Quick, amiable, competent service is how you like your office to be represented. At evaluations of staff, these qualities need to be reinforced. Entry of data into the electronic medical record must be as accurate as possible so that you and others can easily access dependable records in your practice and hospital. This electronic record is impressive to patients and creates a sense that they are in a technologically advanced setting.

Hopefully, the appointment schedule runs on time. Patients often value their time as much as you do. There will be days when surgery runs overtime, an outpatient shows up in the emergency room, or a patient is found to be in trouble while on rounds. Anticipate these delays as early as possible and have a policy that gives patients the option to reschedule or that estimates a realistic wait time. Generally, patients understand unexpected situations and delays in a hospital; they imagine that if it were them that needed urgent attention, they would appreciate the priority. Your desire to excel in the operating room is self-evident to your staff and patients. Apologize to the long-waiting patient when you arrive late, but only the briefest explanation of what detained you is necessary.

How you dress is a sign of respect for your patient. What is in fashion has changed, and there has been a trend toward informality. An exception is the military and uniform of the day. Sometimes, you or the staff wear surgical scrubs in order to save time when rushing to get to the office. This should be a rare occurrence because, with good planning, the office schedule should not be a reason to hurry an operation. We encourage dressing with the respect that is warranted when you tell a patient he has a chronic disease or a late-stage or incurable cancer. As styles change, consider what you would wear to church, a wedding, a job interview, or a funeral. While a serious medical event is run-of-the-mill for you, the patient sees it as a singular, personal, and even life-changing medical problem. How you dress telegraphs respect or disrespect to the family of a patient and also lets your staff know what is expected of them in the way of appearance.

After a short time in the waiting room, the patient usually sees a nurse or nursing assistant who takes vital signs as part of the physical examination. The basic forms for the review of systems, past medical history, surgical history, and medications and administration times may be entered into the record by the nurse as well. These records need to be reviewed, updated, or corrected by the surgeon at a later point during the evaluation. This record handling is another opportunity to demonstrate professionalism and competency and to reassure the patient. In a teaching setting, the student or resident may start with the patient to gather a history.

A Formal Introduction

During the initial work-up by the nurse, student, or resident, intercede to introduce yourself and explain your team’s roles. The patient and family appreciate a formal introduction. It will help them understand the roles that the nurse practitioner, physician’s assistant, resident, or student plays in filling out the history and physical in the record. To let the patient know you have his or her facts committed to memory, you might review the salient points of their story back to them, asking for confirmation. Alternatively, you can request that the pertinent history is repeated to you again to seal it in your mind.

The Physical Examination

The physical examination can be performed with the team member (nurse, student, or resident) and surgeon together. Usually, this will be the abdominal examination, digital rectal examination, anoscopy, and sigmoidoscopy. To explain why so many people are involved, say “It’s good to have multiple sets of eyes on this so we don’t miss anything” or “I’m going to need a hand with some of the instruments so I have a few helpers.” For male physicians, it is often good practice to have a female member of the team present during the pelvic and anorectal exams of women patients. A team-oriented physical examination also helps to sell your team as a competent unit.

If a sink is in the examination room, wash your hands in front of the patient both before and after the examination. Patients appreciate this after so much publicity regarding the safety promoted by hand washing. Patients do not like to have their bare bottoms exposed, so try to position the table so that the patient’s head faces the door. If you traditionally examine the patient in the knee-chest position, consider installing a curtain to be drawn in front of the exam room door.

Patients feel vulnerable not being able to see what you are about to do. Talk the patient through every part of the examination. Predict what the patient may experience and give a warning that a finger is entering the anus or vagina, or estimate and verbalize the size of an instrument relative to your finger. Let them know that an urgency to defecate is normal and not to move if a cramp occurs. We have found that a letter sent to the patient prior to the appointment which explains that a rectal exam is a standard part of a colorectal first encounter, helps establish a sense of preparedness for this intimate and sometimes uncomfortable part of the exam. Also, suggest to patients that they consider clearing their rectal vault of any contents by self-administering an over-the-counter saline enema 2 h prior to the visit. This is something that, when done in the privacy of home, helps the patient mentally prepare for what may ensue during your examination.

If pain is elicited, perform the painful examination only once. If there is no perception of pain, the step may be repeated by the other examiner, with the introduction “you are going to feel another finger now.” Depending upon the working diagnosis, pain may be predicted with some manipulations, while some exams should not be painful. In any case, an effort to minimize pain will endear you to your patient. For example, lubricate the finger or instrument liberally and be gentle. If you see an obvious fissure, do not feel obligated to perform a digital rectal examination or anoscopy on the first visit. Sometimes, asking the patient to push out against your finger not only relaxes the muscles but gives the patient an action to focus on so that he or she will not immediately tense up when sensing your hand nearby.

Conveying Pathology Results

When biopsies are taken or a biopsy result is outstanding, have the patient schedule an appointment within the week to come back and learn the result and plan the ensuing steps. If the pathology is favorable, consider telephoning the patient to relay the good news. This demonstrates to the patient that you are thinking of him or her. Do not put off the call. Often, the patient is anxious and waiting by the phone. If a weekend is near, and the result is favorable, telephone them with the happy result, even if it is late on Friday night. Waiting and not knowing a pathology result exacerbates patient anxiety. Hearing from you during the “off-hours” especially impresses a patient. If the pathology is foreboding, wait for the scheduled appointment or move the appointment sooner.

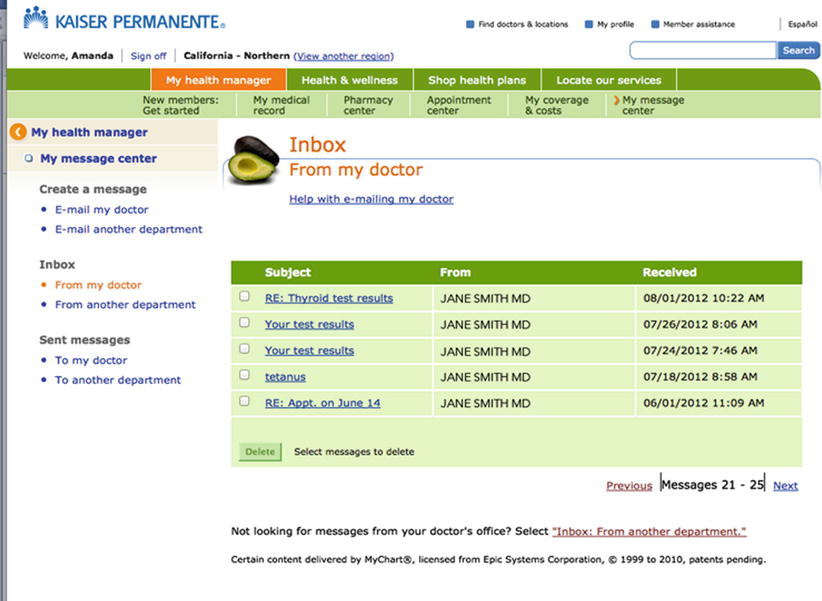

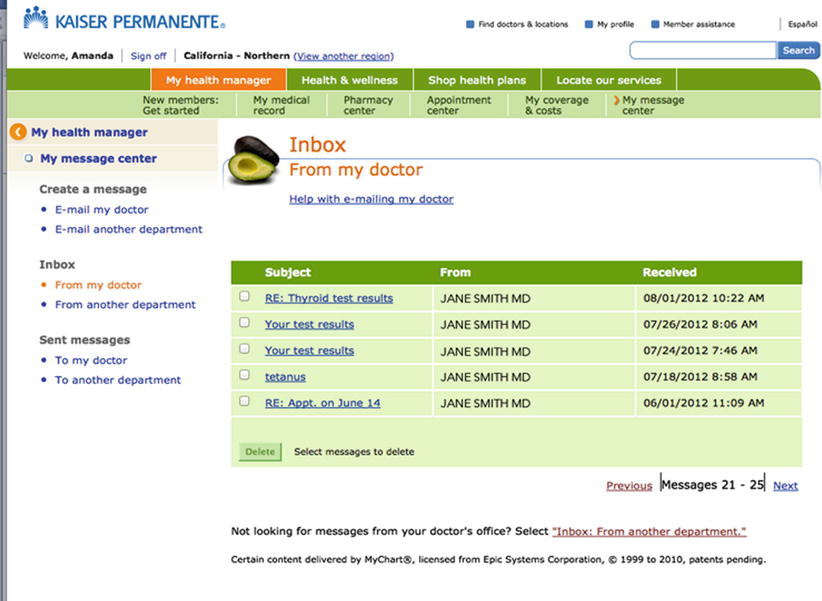

(AS Kumar) I employ e-mail to communicate with many patients about their pathology. After taking a biopsy and before leaving the patient’s side, I discuss the option of receiving the results by e-mail. In an era of exorbinent outpatient co-pays, I sympathize with the patient’s interest in avoiding another face-to-face encounter. If e-mail is an option, we can spend a few extra minutes at the initial encounter itself, talking through the potential next steps based on the outcomes of the pathology report. The e-mail that I ultimately send encloses a digital version of their entire report and includes a summary of my impressions. I ask the patient to reply with a phone number and a good time for me to call to discuss it further. This step empowers the patient, since many like to keep shadow copies of their medical records and also like the opportunity to share the diagnoses with the primary care provider. Sophisticated electronic personal health systems employ a web portal where patients log in to see their personal health record and interact with their physicians. This allows them to access their laboratory and pathology reports and correspond with their physicians via the secure portal (Fig. 1.2) [1]. Nonetheless, I am careful to get the patient’s permission before sending an e-mail, since the Internet is not a fully private environment. Many institutions’ e-mail servers provide a disclaimer statement (Fig. 1.3) that underscores that your e-mail is a confidential communication to them. I take the extra step of committing e-mails to and from patients in the electronic health record (EHR) under the “letter” or “correspondence” sections. Similar to a “phone note,” this step makes your electronic conversation with the patient or providers an integral part of the medical chart.

Fig. 1.2

Internet portals can allow patients to access their personal health records (With permission from Kaiser Permanente [1])

Fig. 1.3

Confidentiality statements employed by institutions’ Internet transmissions at (a) MedStar Health (b) Memorial Sloan Kettering and (c) Chesapeake Potomac Regional Cancer Center

The Team and Teaching

Key concept: Each member of the team plays a critical role—ensure the patient understands who everyone is and what that role encompasses. Have several different platforms (i.e., brochures, videos, online links, support groups) of educational resources available for your patients.

The Team’s Role

At a convenient break during the first outpatient visit, explain that the team consists of a nurse, nurse practitioner, physician’s assistant, residents, other surgeons, ostomy nurses, or others who will be working with the patient and emphasize that these same people may be present at the hospital or during follow-up. For example, you may volunteer that they might be speaking to the nurse by telephone to answer questions, to residents or partners for hospital rounds, or to nurse practitioners or physician’s assistants during follow-up. This never frees you as the surgeon from your ultimate responsibility—rounds and follow-up are a part of your primary obligation to your patients.

The patient may wonder why there are so many people involved. You can assure them that each team member plays a valuable role, that many minds are dedicated to their problem, and that not a step will be missed. It also serves to keep everyone educated. For a colon and rectal surgery resident or a chief resident, you can add that they are a trained (often board certified) general surgeon or are about to finish a rigorous general surgery-training program. The residents provide an additional observer of progress or problems and a level of continuity if surgery and hospitalization are contemplated.

Educational and Informational Resources for Patients

Repetition is a form of teaching. Direct your patient to the many resources for more information, such as pamphlets or videos. Educational aids are readily available from several sources. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) have brochures and videos that address the various diseases and surgeries of the colon, rectum, and anus. Such educational references can set up as hyperlinks on your practice’s website. Putting up a brochure rack (Fig. 1.4) is a small investment, but videos and customized websites may be costlier. As an alternative, provide the patient with the links to websites you trust. Both ASCRS and SAGES have patient-specific links (Fig. 1.5a–c) [2, 3], which also include written and video testimonies from patients who have had specific colorectal issues [4]. Take a few minutes to browse the web for materials relevant to the patient’s situation. An endorsement from you will be more productive than leaving your patient adrift on Internet search engines.

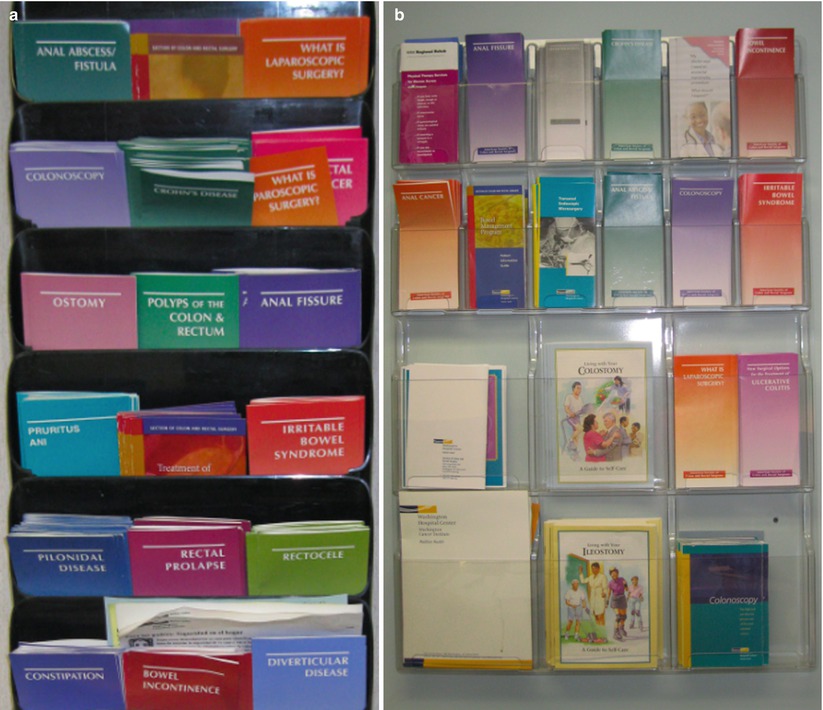

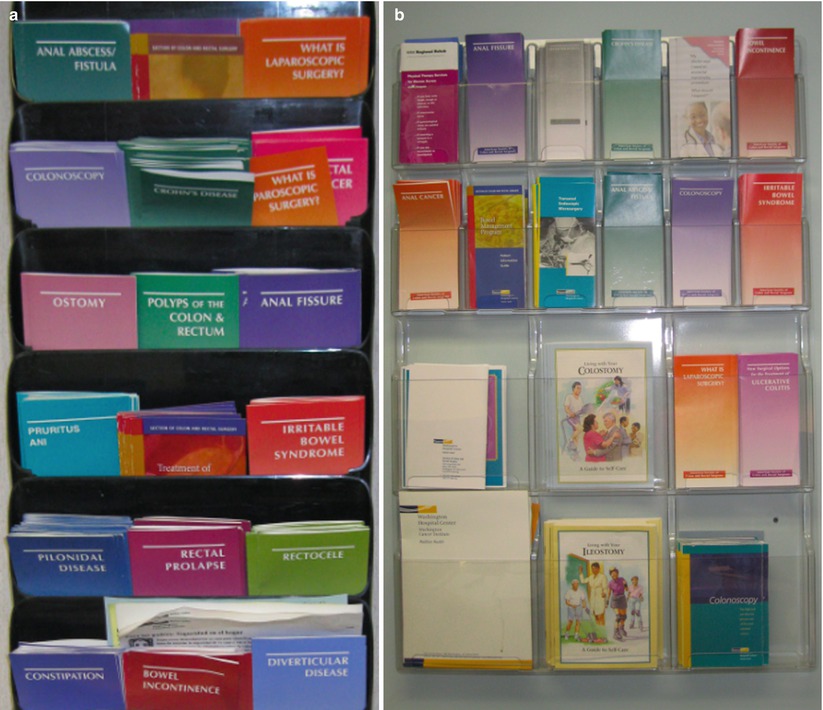

Fig. 1.4

Brochure racks are a simple and affordable solution for patient education. (a) An example of what is displayed in a patient exam room; (b) in our nurses’ room, information about ostomies is also provided

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree