Erik B. Kistler and Jonathan L. Benumof

INTRODUCTION

Endotracheal intubation can be lifesaving for the patient in need of a definitive airway. An endotracheal tube (ETT) provides a secure respiratory conduit from the outside environment to the airway, enabling ventilation, oxygenation, relief of airway obstruction, control of respiratory acid-base status, and protection against aspiration. However, endotracheal intubation is a potentially dangerous intervention, especially when attempted emergently with inadequate preparation, and should not be undertaken lightly. A patient requiring out-of-operating room emergent intubation should be considered as having a potentially difficult airway and treated accordingly.

PREPARATION AND ENVIRONMENT

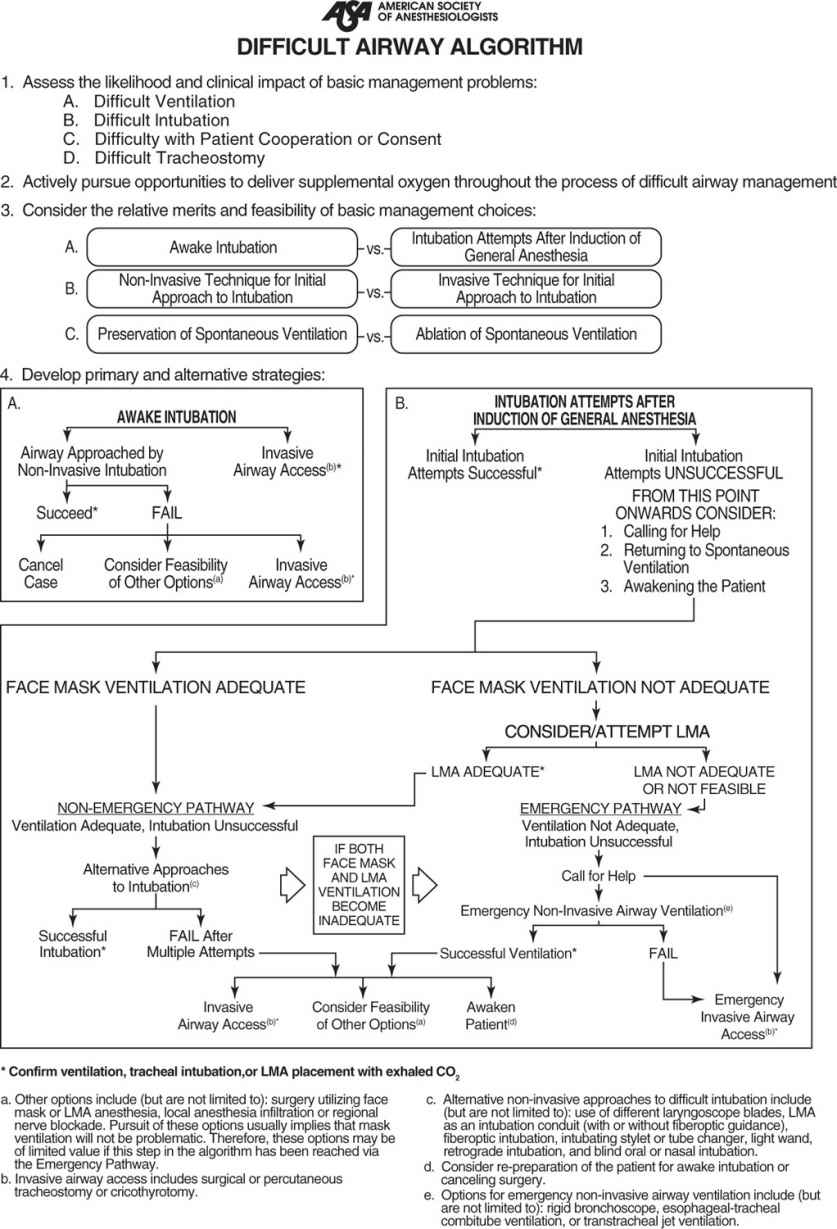

Arguably, the most important modifiable variable in securing a difficult airway is preparation. Personnel capable of securing the airway as well as ancillary staff (i.e., nursing, respiratory therapists) must be available and a definitive plan should be in place. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Difficult Airway Algorithm (Fig. 36-1) is a widely used schema and is included at the end of the chapter as an exemplary guide. Finally, it is imperative that equipment, including rescue options, be available for immediate use. A Difficult Airway cart that is stocked, accessible, and contains equipment familiar to the operator can be lifesaving.

Figure 36-1. ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm. (From American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1269–1277.)

RECOGNITION AND INTERVENTION IN THE DIFFICULT AIRWAY

Unlike scheduled operating room procedures where the patient’s airway is carefully examined and comorbidities acknowledged and optimized, the patient with the difficult airway may present as a completely unknown entity, encountered for the first time in cardiopulmonary arrest. Therefore, it is not always possible to adequately assess the airway beforehand. Factors contributing to a difficult endotracheal intubation may be divided into anatomical and pathological categories. Anatomic factors are listed in Table 36-1. Pathologic factors such as an unstable cervical spine secured by halo stabilization devices or cervical collars, airway edema, blood, secretions and pus, and facial hair also contribute to the difficult airway. Every effort should be made to determine the presence of these risk factors as is clinically feasible. In general, earlier intervention should be considered if it is perceived that the airway may be difficult to manage.

The decision of when (and if) to intervene to secure the airway is often complex and involves a consideration of many different variables. These factors include but are not limited to patient oxygenation(Spo2) in relation to the applied oxygen (FIO2) as reflected by the difference in oxygen tension between the alveolus and arterial circulation (i.e., the A–a gradient), hypo- or hypercarbia (Paco2) in relation to minute ventilation and tidal volume, adventitious breath sounds, distended abdomen, fluid balance, use of accessory muscles of breathing, the patient’s ability to speak in complete sentences, anxiety, and blood pressure and heart rate (as indices of Central Nervous System [CNS] activation). Sometimes it is the anticipated fate of other organ systems (brain, heart, liver, etc.) that determine when and if airway intervention is necessary.

Components of the Airway Preoperative Physical Examination |

Airway Examination Component | Nonreassuring Findings |

1. Length of upper incisors | Relatively long |

2. Relation of maxillary and mandibular incisors during normal jaw closure | Prominent “overbite” (maxillary incisors anterior to mandibular incisors) |

3. Relation of maxillary and mandibular incisors during voluntary protrusion of cannot bring | Patient mandibular incisors anterior to(in mandible front of) maxillary incisors |

4. Interincisor distance | Less than 3 cm |

5. Visibility of uvula | Not visible when tongue is protruted with patient in sitting position (e.g., Mallambati class greater than II) |

6. Shape of palate | Highly arched or very narrow |

7. Compliance of mandibular space | Stiff, indurated, occupied by mass, or nonresilient |

8. Thyromental distance | Less than three ordinary finger breadths |

9. Length of neck | Short |

10. Thickness of neck | Thick |

11. Range of motion of head and neck | Patient cannot touch tip of chin to chest or cannot extend neck |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree