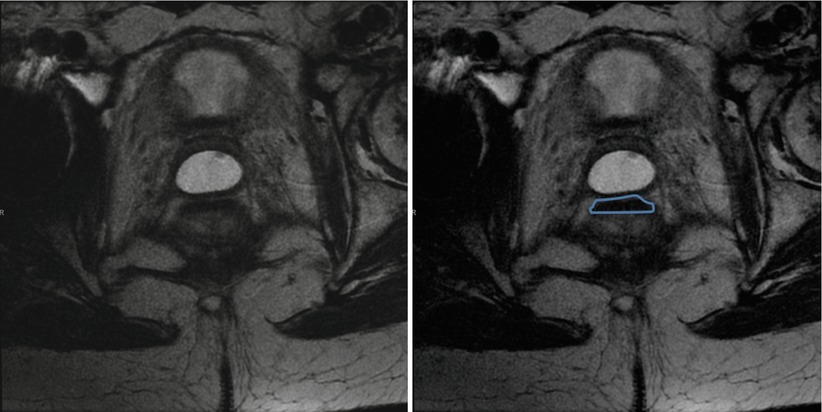

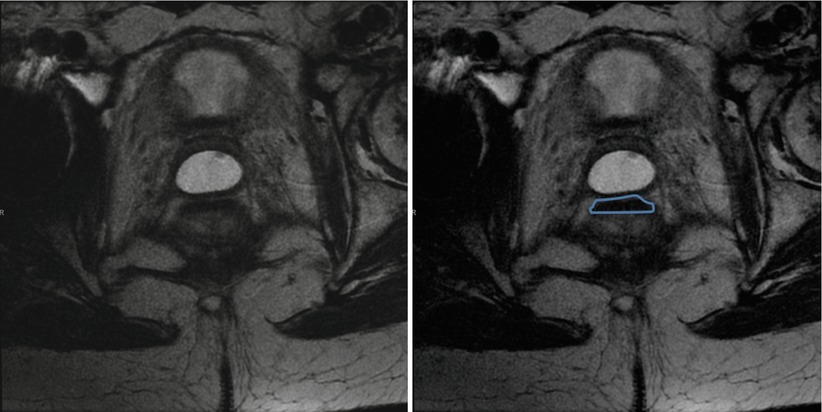

Fig. 16.1

(a) Area of irregularity detected at digital rectal examination that prompted full-thickness excisional biopsy with TEM. (b) Final pathology revealed the presence of residual cancer cells (ypT2)

Endoscopic assessment is also very important. Whitening of the mucosa and telangiectasia are usually seen in patients with a complete clinical response (Fig. 16.2). The presence of any ulceration or mucosal irregularity missed on DRE should prompt additional investigations and usually rule out a complete clinical response. Frequently, DRE may have to be reassessed after endoscopic guidance of any findings suggestive of residual cancer. During flexible or rigid proctoscopy, biopsies are frequently considered for assessment of response. If there is clinical evidence (DRE and endoscopic) of a cCR, forceps biopsies should be interpreted with caution since a negative biopsy cannot rule out microscopic residual cancer [29]. On the other hand, in the presence of clinical evidence of residual cancer (incomplete response), endoscopic biopsies are also rarely useful, except for convincing patients that there is residual disease there! Even in the presence of negative endoscopic biopsies, patients with incomplete clinical response should not be offered a nonoperative approach [29]. If they are resistant to radical resection or medically unfit, the least we would offer is a full-thickness excisional biopsy, preferably with the use of transanal endoscopic microsurgery. This “excisional biopsy,” primarily considered as a diagnostic procedure, may be appropriate for patients with small (≤3 cm) lesions. However, we would restrict this to patients with low residual lesions that would otherwise require an abdominal-perineal excision or a coloanal intersphincteric resection as a radical alternative [30]. Appropriate pathological information regarding ypT classification, tumor regression grade, lymphovascular/perineural invasion, and resection margins may allow final decision regarding the need for total mesorectal excision and proctectomy.

Fig. 16.2

Endoscopic view of a complete clinical response with obvious whitening of the mucosa and the presence of significant telangiectasia

Local Excision of the Tumor Site

Key Concept: Final pathological assessment after local excision will help guide your management. Use “diagnostic” TEM judiciously. Postoperative healing problems and significant scarring may lead to untoward surgical consequences if further resection is needed.

It has been our policy to offer strict follow-up to patients with final pathological specimen showing ypT0 after this “diagnostic” transanal local excision. This is due to the fact that the risk of lymph node metastases among these patients has been shown to be very low in the setting of neoadjuvant CRT and long (≥8 weeks) intervals. This is already true for unselected patients with ypT0, where the risk of nodal metastases is well under 10 % and in most cases less than 5 % [31–33]. However, with the significant improvements in radiological imaging, particularly with high-resolution magnetic resonance (MR) with the use of diffusion-weighted series and other lymphotropic agents, selection of patients with ycT0N0 is expected to further improve [34]. On the other end of the spectrum, patients with unsuspected residual ypT3, lymphovascular invasion, positive resection margins, and more than 10 % of viable residual cancer cells have been recommended immediate radical surgery.

Equally challenging cases are those with intermediate residual cancers: ypT1 or early ypT2 (restricted to the superficial muscular layer) cancers without lymphovascular invasion or other unfavorable pathological features. In the presence of negative margins (≥5 mm), it has been our policy to follow up these patients without immediate radical surgery, only if they would otherwise require an abdominal-perineal excisions or coloanal anastomosis. In this strategy of offering patients with small superficial residual cancers, radiologically staged as ycN0, a local procedure is quite appealing. However, there are at least two main drawbacks to this treatment strategy. First, healing of the rectal defects determined by local excision after neoadjuvant CRT is quite challenging and painful, particularly those closer to anal verge [35, 36]. Healing problems are much more frequent and may take as long as 8 weeks to completely heal. Even though severe complications are not frequent, pain is significant. The second drawback is that sphincter preservation may be compromised after performance of full-thickness local excision in this setting. A few studies have addressed this issue and reported that patients requiring radical resection after FTLE always ended up with an APR, even though they originally were considered candidates for a sphincter-preserving procedure [30, 37]. Both of these issues should be kept in mind when offering patients “diagnostic” or “therapeutic” local excision after partial response.

Why not offer patients with a cCR transanal local excision for the histological confirmation of ypT0? As mentioned above, healing of local excision defects following neoadjuvant CRT is not as simple as after local excision alone. The rates of wound dehiscence may be quite significant. In this setting, not only is pain an issue, but also significant scarring following delayed healing may develop which will make patient follow-up even more difficult. Even though ypT0 may be associated with lower risk of local failures, the risk is not zero and the patient still requires appropriate follow-up. Distinction between local recurrence in a rectal wall following wound dehiscence after a local excision with or without rectal stenosis may be quite challenging. Therefore, we believe that follow-up is considerably facilitated by preservation of rectal wall integrity with the watch and wait approach allowing for earlier detection of eventual recurrences in addition to superior functional outcomes.

Radiological Imaging

Key Concept: Radiological imaging should be used to confirm clinical findings. In the absence of complete clinical response, do not look for radiological evidence to support nonoperative management. It is better to fail identification of complete response in favor of radical surgery and end up with a pCR than to miss residual cancer and end up with an early local recurrence or tumor regrowth.

Radiological assessment of response is of paramount importance to appropriately select patients for an alternative treatment strategy such as the “watch and wait” approach following a complete clinical response. As a matter of fact, the developments in radiological imaging, including both PET/CT and MR, have been quite significant. Proper magnetic resonance imaging with the use of diffusion-weighted techniques is now used routinely for the assessment of response in these patients. Currently, we would only consider a true complete responder (1) in a patient showing low signal intensity area replacing the area of the previous tumor or (2) in a patient with no detectable abnormalities in standard MR associated with no evidence of disease on clinical and endoscopic examination (Fig. 16.3). A recent publication has reported three different patterns of low signal intensity that are compatible with a complete clinical response: minimal fibrosis, transmural fibrosis, and irregular fibrosis [38]. Others have attempted to estimate tumor regression grades (as described for pathological assessment) [39] by standard MR imaging. [40] In addition, diffusion-weighted MR series should provide evidence of absence of restriction to diffusion to fulfill the criteria for a radiological complete response [41]. In our previously reported experiences with this “watch and wait” treatment strategy, MR imaging was not available to a significant proportion of patients [42]. Therefore, there is a hope that incorporation of these findings for the selection of patients with complete clinical response will significantly impact the outcomes of the watch and wait strategy. The presence of mixed signal intensity (Fig. 16.4) within the area of the previous cancer should raise a suspicion of an incomplete clinical response (Fig. 16.5). In addition to the assessment of the rectal wall, the mesorectum is also at risk for the presence of residual cancer despite complete primary regression (ypT0N1). Therefore, MR imaging should also provide the colorectal surgeon with information regarding possible mesorectal (or even lateral node) involvement regardless of primary tumor response (Fig. 16.6).

Fig. 16.3

Magnetic resonance of a patient with a complete clinical response and low signal intensity area within the rectal wall (transmural fibrotic pattern). Such radiological finding is consistent with a complete clinical response

Fig. 16.4

Magnetic resonance of a patient with a complete clinical response but mixed signal intensity (arrow) within the rectal wall. PET/CT showed FDG uptake and radical surgery confirmed the presence of residual cancer ypT2N0

Fig. 16.5

Flowchart of the watch and wait strategy

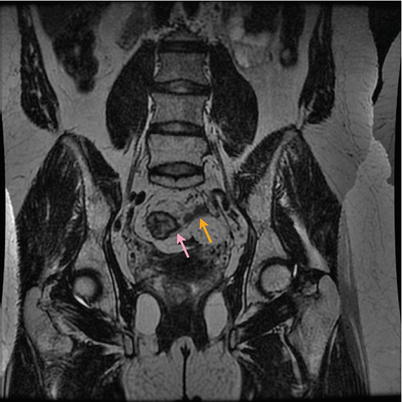

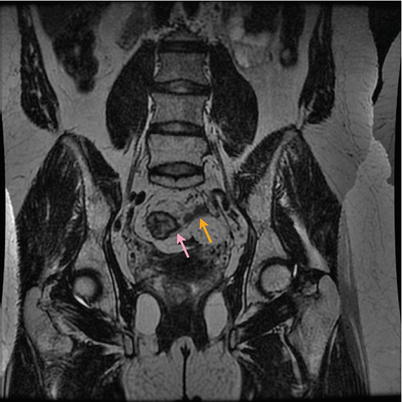

Fig. 16.6

Magnetic resonance showing the presence of mesorectal involvement (orange arrow) despite complete clinical response (pink arrow) of the primary tumor (ycT0N1). Radical surgery confirmed the presence of ypT0N1 disease

Molecular imaging may also play a role in the assessment of tumor response. PET/CT imaging offers information on tumor metabolism in addition to standard radiological anatomical features. In this setting, PET/CT has been used for the assessment of tumor response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy [12, 43]. In addition to the visual identification of FDG uptake within the area of the rectal wall harboring the tumor or within the mesorectum, PET/CT allows the estimation of the metabolism profile. Standard uptake values are direct estimations of tissue metabolism and may be used for the distinction of residual inflammatory changes and residual cancer. Measurement of SUV in two different intervals from FDG injection is routinely performed (at 1 and 3 h) and allows two distinct patterns (dual time) of metabolism. Increases in SUVs (between 1 and 3 h) suggest the presence of residual cancer whereas decreases suggest inflammatory or fibrotic changes [28]. Even though we have used PET/CT to distinguish between complete and incomplete responses in the setting of a prospective study with acceptable overall accuracy (85 %), PET/CT may not be appropriate for routine use for this purpose, mainly due to increased cost and need for multiple studies with significant radiation exposure [12]. Instead, the use of this molecular imaging modality should perhaps be considered for patients with significant discordant results between studies, particularly between clinical and radiological findings.

Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA)

Key Concept: Pre- and posttreatment CEA can help determine clinical response and may guide additional evaluation.

Pretreatment CEA levels have been shown to be predictors of response to neoadjuvant CRT and ultimately survival [39, 44]. Posttreatment CEA levels are also relevant and normal levels after CRT have been associated with increased complete clinical response rates [45]. Abnormal CEA levels before or after CRT should raise the suspicion of incomplete response to CRT and/or metastatic dissemination. In this setting, abnormal CEA levels should lead to a more liberal use of PET/CT imaging for the assessment of tumor response since it may also allow detection of unsuspected metastatic disease in addition to the diagnosis of incomplete response (Fig. 16.5).

Summary Pearls: Final Decision Management

Key Concept: Putting it altogether to determine the optimal management requires consideration of the clinical, endoscopic, radiological, and laboratory findings, in addition to the patient’s overall health and desires.

Patients are usually assessed for tumor response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation at least 8–10 weeks from treatment completion regardless of the exact treatment regimen used. Clinical and endoscopic features are assessed in the clinic using digital rectal examination and rigid proctoscopy. Flexible proctoscopy is used solely for video documentation or for situations where endoscopic biopsies are required. Again, endoscopic biopsies are rarely useful due to the considerably low negative predictive values. Still, they may be useful to convince the patient that there is residual cancer. Colorectal surgeons should not be obsessed for the obtainment of positive biopsies prior to indication for radical surgery. Clinical assessment showing incomplete response should suffice. CEA levels should be normal both before and after treatment; otherwise, additional studies are strongly recommended.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree