, Carmen L. Menendez2, Rodolfo Montironi3 and Liang Cheng4

(1)

Department of Surgery and Pathology, University of Cordoba Faculty of Medicine, Cordoba, Spain

(2)

Pathology Department, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Spain

(3)

Department of Biomedical Sciences and Public Health, Polytechnic University of the Marche Region (Ancona), Torrette, Italy

(4)

Department of Pathology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

4.4 Yolk Sac Tumor

4.5 Polyembryoma

4.7 Teratoma

4.8 Burned Out GCTs

4.20 Other Rare Tumors

4.32 Sperm Granuloma

4.34 Cysts

4.35 Ectopic Tissues

4.1 Basic Anatomy and Histology

The adult testis is an egg-shaped organ that hangs in the scrotum from the spermatic cord, the retro-epididymal surface, and the scrotal ligament. Mean testicular diameter is 4.6 cm for the longest axis.

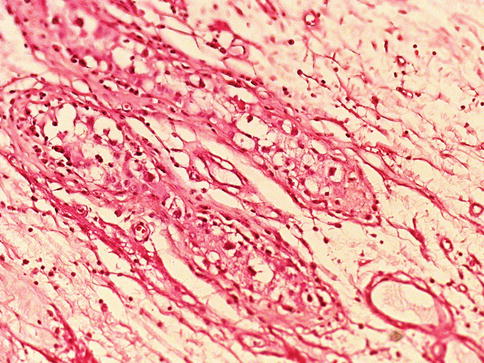

The tunica albuginea consists of three connective tissue layers: an outer layer containing a mesothelial lining that rests on a basal lamina (tunica vaginalis), a middle layer of dense fibrous tissue, and an inner layer of loose connective tissue (tunica vascularis) with nerves, and blood and lymphatic vessels. The thickness of tunica albuginea increases with age. Myofibroblasts are common in the tunica albuginea.

The seminiferous tubules comprise about 80 % of testicular volume. The tubular lining of germ cells and Sertoli cells is surrounded by a lamina propria. Sertoli cells are columnar cells that extend from the basal lamina to the tubular lumina.

Sertoli cell nucleus is located near de basal lamina, and is triangular with indented outline. The nucleolus is central and voluminous and that differentiates Sertoli cells from germinal cells (show coarse chromatin granules and variable number of nucleoli) in routine histologic sections.

Charcot-Botcher crystals are often seen in the cytoplasm. Sertoli cells also produce several components of the seminiferous tubule wall, including type IV collagen, laminin, and heparin sulfate-rich proteoglycans.

The germs cells include spermatogonia, primary and secondary spermatocytes, and spermatids (primary and secondary). These can be recognized on conventional histologic evaluation.

The interstitium between the seminiferous tubules contains Leydig cells, macrophages, mast cells, fibroblasts (CD34+), neuron-like cells, myofibroblasts, blood and lymphatic vessels, and nerves. Leydig cells have spherical eccentric nuclei with one or two nucleoli. The eosinophilic cytoplasm is abundant, and it contains lipofuscin granules. Reinke crystalloids are seen only in Leydig cells of adults.

The testis is supplied by the testicular artery, which arises from abdominal aorta.

The inner two thirds of the testis parenchyma is drained by centripetal veins that follow interlobular septa to the mediastinum testis. The out third is drained by centrifugal veins that lead to the tunica albuginea. Both types of veins anastomose, and leave the testis by the veins from pampiniform plexus which drains de tested via the spermatic cord.

Lymphatic vessels are poorly developed in the testes. Afferent nerve endings form corpuscles similar to those of Meissner and Pacini seen in the tunica albuginea. Efferent innervation is mainly supplied by neurons of the pelvic ganglia.

The rete testis is a network of channels and cavities that connect the seminiferous tubules with the ductuli efferentes. The epithelium of the mediastinal rete testis consists of flattened cells interspersed with small areas of columnar cells. Both cell types have numerous microvilli and a single cilium on their free surface and contain keratin and vimentin filaments.

The fetal testis has three types of germ cells known as gonocytes (OCT4+, CD117+), intermediate germ cells (OCT4 +/−, CD117−), or spermatogonia (OCT4−, CD117−). The prepubertal testis develops into three phases:

(i)

Newborn and perinatal period showing solid tubules with centrally located Sertoli cells and gonocytes. At the age of 6 months there are no gonocytes since they have been transformed in spermatogonia. Leydig cells are similar to those seen in adults.

(ii)

In infants, after the age of 6 months the testis remains at rest after the age of 3 years. Then it is observed a margination of the cells imparting a pseudo-luminal appearance to the tubules. These include Sertoli and undifferentiated cells and some spermatogonia. Leydig cells have decreased and there is low level of testosterone.

(iii)

In boys, from age 9 years but mainly between the age of 13 and 15 years, interstitial stromal cells are transformed in adult Leydig cells that produce testosterone under LH stimulation. LH also stimulates development of germ cells, growth of tubules, and development of central lumen.

Undescended testis is frequently smaller than contralateral descended testes. Histologically may present slight alterations only (histology or prepubertal testis), or may present testes with marked germinal hypoplasia showing spermatogonia irregularly distributed, frequently within the same lobule.

In severe cases, the testes show severe germinal hypoplasia with giant spermatogonia, dark nuclei and edematous interstitium.

With age and decreasing hormonal levels, changes of atrophy are frequent after the age of 70 years. After the age of 80 years, there is always certain degree of fibrosis in the tubular wall, but some degree of spermatogenesis persists.

4.2 Classification of Tumors and Tumor-Like Conditions

Testicular tumors are classified according to the WHO (2004) classification (Table 4.1) and represent a heterogeneous group of neoplasms. Although rare, germ cell tumors have always been of great interest and nowadays can be cured in more than 90 % of cases.

Table 4.1

WHO 2004 classification of testicular tumors

Germ cell tumors

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia, unclassified

Other types

Tumors of one histologic type (pure forms)

Seminoma

Seminoma with syncytiotrophoblastic cells

Spermatocytic seminoma

Spermatocytic seminoma with sarcoma

Embryonal carcinoma

Yolk sac tumor

Trophoblastic tumors

Choriocarcinoma

Trophoblastic neoplasms other than choriocarcinoma

Monophasic choriocarcinoma

Placental site trophoblastic tumor

Teratoma

Dermoid cyst

Monodermal teratoma

Teratoma with somatic type malignancies

Tumors of more than one histologic type (mixed forms)

Mixed embryonal carcinoma and teratoma

Mixed teratoma and seminoma

Choriocarcinoma and teratoma/embryonal carcinoma

Others

Sex cord/gonadal stromal tumors

Pure forms

Leydig cell tumor

Malignant Leydig cell tumor

Sertoli cell tumor

Sertoli cell tumor lipid rich variant

Sclerosing Sertoli cell tumor

Large cell calcifying Sertoli cell tumor

Malignant Sertoli cell tumor

Granulosa cell tumor

Adult type granulosa cell tumor

Juvenile type granulosa cell tumor

Tumors of the thecoma/fibroma group

Thecoma

Fibroma

Sex cord/gonadal stromal tumor incompletely

differentiated

Sex cord/gonadal stromal tumor, mixed forms

Malignant sex cord/gonadal stromal tumor

Tumors containing both germ cell and sex cord/gonadal

stromal element Gonadoblastoma

Germ cell–sex cord/gonadal stromal tumor, unclassified

Miscellaneous tumors of the testis

Carcinoid tumor

Tumors of ovarian epithelial types

Serous tumor of borderline malignancy

Serous carcinoma

Well-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma

Mucinous cystadenoma

Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma

Brenner tumor

Nephroblastoma

Paraganglioma

Hematopoietic tumors

Tumors of collecting ducts and rete

Adenoma

Carcinoma

Tumors of paratesticular structures

Adenomatoid tumor

Malignant mesothelioma

Benign mesothelioma

Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma

Cystic mesothelioma

Adenocarcinoma of the epididymis

Papillary cystadenoma of the epididymis

Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor

Mesenchymal tumors of the spermatic cord and testicular adnexae

Secondary tumors of the testis (metastases)

4.2.1 Germ Cell Tumors

4.2.1.1 Overview

Carcinoma in situ (CIS) cells develop from primordial germ cells and early gonocytes. Placenta-like alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) was the first marker described in CIS and seminoma. Of greater importance for an understanding germ cell oncogenesis was the discovery of factors essential for maintaining pluri-potency and self-renewal capability of embryonic stem cells CD117 (c-KIT) and OCT-3/4 (OCT-4).

The best support for the theory of the common origin of the germ cell tumors (GCTs) is the presence of the iso-chromosome i(12p), a chromosome with four short arms present in about 80 % of GCTs regardless of their morphology. Non-seminomatous GCTs (NSGCTs) usually have more i(12p) copies of than Seminomas.

GCTs are rare tumors and account for only 1–2 % of malignant tumors in males. White men living in Western industrialized countries show the highest incidence rates, whereas black men in Africa show the lowest. The incidence in Asiatic men lies somewhere between both extremes.

Well-established epidemiologic causes of GCTs are listed in Table 4.2. The average age of patients at presentation significantly correlates with the pathologic type of GCTs (Table 4.3).

Table 4.2

Causes of germ cell tumors and the relative risk

Cryptorchidism

2–17-fold

Contralateral GCT

25-fold

Familial GCT

3.8–7.6-fold

Male infertility

1.6–10-fold

Gonadal dysgenesis

30–50-fold

Testicular atrophy

2.7–12.7-fold

Surgery (trauma)

Low risk

Occupational exposure

1.1–14.7-fold

Mother older than 30 years old

Low risk

Mother breast cancer

Low risk

Birth weight <2.5 kg

1–13.5-fold

High socioeconomic status, microlithiasis, infectious diseases

probably no risk

Table 4.3

The typical age presentation of patients with germ cell tumors

Seminoma

35–40 y

Extremely rare before puberty

Spermatocytic seminoma

Average 52 y

Rare after 70 y

Embryonal carcinoma

Average age 30 y

Rare before puberty and after 50 y

Teratoma (pure form)

Average age in children 20 months

Rare after the age of 4 y

Adults 20–30 y

Choriocarcinoma

Average age 25–30 y

Yolk sac tumor (pure form)

Average age 25–30 y

15–40 % of GCTs in children

Mixed forms

33 y if seminoma prevails

28 y if NSGCT prevails

4.2.2 Intratubular Germ Cell Neoplasia, Unclassified (IGCNU)

4.2.2.1 Overview

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia (IGCNU) is the official name of the lesion, better known as carcinoma in situ of the testis or testicular intratubular neoplasia. The adjective “unclassified” is utilized to emphasize that the morphology of the tumor cells does not permit an assignment to a definite type of GCT.

If the intratubular tumor cells can be definitely recognized, the adjective intratubular is used in connection with the respective name of the GCT (i.e. intratubular embryonal carcinoma or intratubular seminoma). The prevalence of IGCNU in healthy men is estimated 0.4–0.8 % and about 1 % in infertile men. In cryptorchid testes of adults the frequency is 2–4 %. With the exception of spermatocytic seminoma, atypical germ cells are constantly found (in 98 % of the healthy tissue surrounding invasive GCTs of adults (Table 4.4).

Table 4.4

Prevalence of intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified

Infertile men

1.0 %

Healthy men

0.4–0.9 %

Intersex

20 %

Cryptorchid testis of adults

2–4 %

Retroperitoneal ‘extragonadal’ GCT

49 %

Patients with germ cell tumor–contralateral testis

4–6 %

4.2.2.2 Pathology

The IGCNU cells are attached to the usually thickened basement membrane and push the Sertoli cells towards the lumen of the seminiferous tubules. The cytoplasm is clear because of the large amount of glycogen (PAS+). The nuclei are bigger than those of spermatogonia and contain one or more nucleoli (Fig. 4.1).

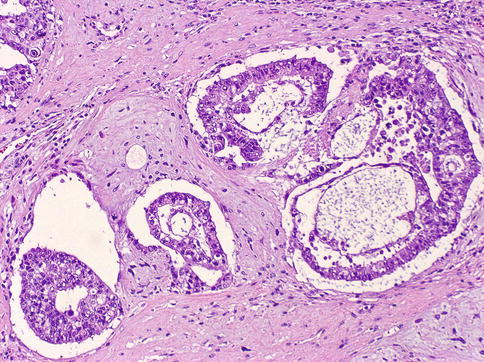

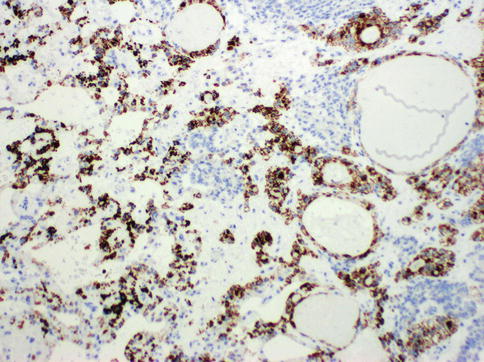

Fig. 4.1

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified

Mitoses are frequent but may be overlooked. IGCNU can also spread in a ‘pagetoid’ pattern into the rete testis or present as microinvasive lesion. Lymphocytic infiltration of the interstitial tissue surrounding the affected, mostly clearly narrowed tubules is frequent.

4.2.2.3 Immunohistochemistry

PLAP, c-KIT (CD117), and OCT 3/4 antibodies are positive, and can thus easily be distinguished from non-reacting normal spermatogonia, which are PAS-. IGCNU are aneuploidy and gain i(12p) copies only shortly before they become microinvasive.

4.2.3 Germ Cell Tumors of One Histologic Type

Seminoma is the most common pure germ cell tumor followed by embryonal carcinoma. Pure yolk sac tumor occurs almos exclusivelly in infants. Main clinico-pathologic characteristics of these tumors follow.

4.2.4 Seminoma

About half of intrascrotal tumors are seminomas. Patients are on average 30–34 years of age. Most common GCT in its pure form.

4.2.4.1 Pathology

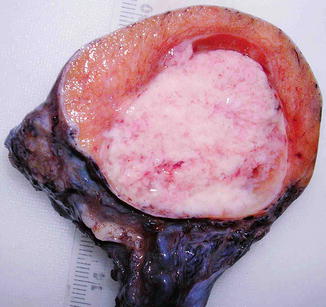

The affected testis is usually enlarged, but can be normal or even atrophic. The tumor is uniform, cream-coloured or pink, and always well-circumscribed. The cut surface is lobulated and the consistency varies from soft to firm, depending on the amount of tumor stroma. Nowadays in the majority of cases the tumors are confined to the testis, but extension to the epididymis and spermatic cord can occur and were very frequent (43 %) in old series. In large tumors necrosis may occur (Fig. 4.2).

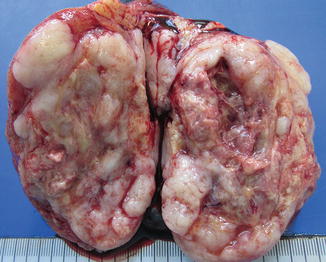

Fig. 4.2

Gross features of testicular seminoma

Hemorrhage is not frequent and can indicate the presence of a non-seminomatous tumor component. Small hemorrhagic spots are very characteristic of seminoma with syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells.

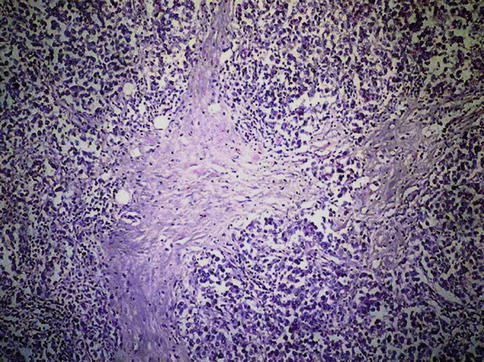

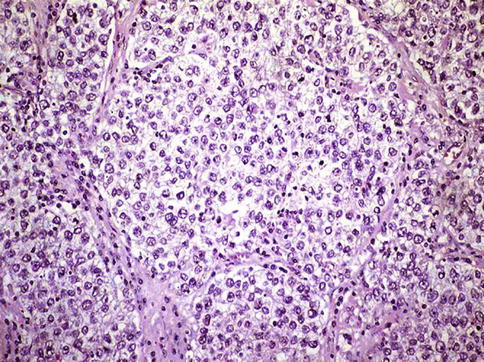

Seminoma cells are rather uniform with a rounded shape and a mostly clear, glycogen-(PAS-positive) and lipid-rich cytoplasm. In ‘classical’ seminomas tumor cells typically grow in cords and/or nests separated by more or less delicate trabeculae. In some cases, however, small nests of tumor cells are surrounded by abundant fibrotic tissue (Figs. 4.3, 4.4, 4.5, 4.6 and 4.7; Table 4.5).

Fig. 4.3

Seminoma. Low power microscopic features of neoplastic seminoma cells with mild lymphocytic infiltration

Fig. 4.4

Seminoma. Large nests of neoplastic seminoma cells showing clear cytoplasm and scarce connective tissue

Fig. 4.5

Lymphocytes in stroma are common in some seminomas

Fig. 4.6

High power view of seminoma cells

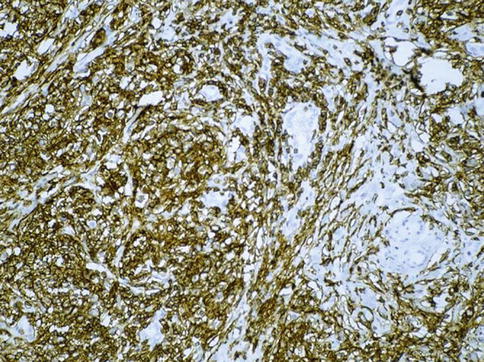

Fig. 4.7

PLAP expression in seminoma

Table 4.5

Different pathologic variants of seminoma

Intratubular seminoma

Interstitial seminoma

Tubular seminoma

Cribriform seminoma

Pseudoglandular seminoma

Microcystic seminoma

Seminoma with high mitotic rate

Lymphocytic infiltration of tumor stroma is a typical feature of about 90 % of seminoma and can be used as a diagnostic criterion in poorly preserved, improperly processed surgical specimens.

The amount of lymphatic infiltration varies from some few lymphocytes to heavy infiltration and formation of lymphoid follicles. Furthermore, in about one-third of seminomas, epithelioid granulomas also develop.

Lymphocytic infiltrates probably represent a true immunologic reaction directed against the tumor. In fact, in old series, observed before the introduction of new therapy protocoling, lymphocyte rich seminomas did significantly better than those without lymphocytes.

4.2.4.2 Morphologic Variations

Seminoma with syncytiotrophoblastic cells: using H&E staining multinucleated giant cells are detected in about 7 % of seminomas, mostly in the surroundings of vessels. With immunohistochemistry against hCG, however, positive cells are present in about 25 % of all cases. The presence of hCG cells should not be confused with true choriocarcinomas.

Accumulation of edematous fluid in interstitial tissue gives the tumor a microcystic or cribriform (seminoma) appearance.

In pseudoglandular and tubular seminoma, tumor cells form small gland-like clefts.

The name intratubular or interstitial seminoma derives from the predominant way the tumor cells spread.

The formerly anaplastic or atypical seminomas have been renamed as seminomas with high mitotic rate, which is indeed more appropriate because the degree of cellular anaplasia is not higher than in the classical type. High proliferative activity measured by counting mitoses or cells positive for proliferation markers (Ki 67) does not, however, negatively influence the course of the disease (Table 4.5).

4.2.4.3 Immunohistochemistry

Seminoma cells react with many different antibodies. For diagnostic purposes, however, only a few are really important. The most frequent misdiagnosis is to confound seminoma with embryonal carcinoma, which usually happens when the surgical specimen is improperly fixed.

Seminoma cells stain with CD 117 (c-kit) and do not react with CD 30 antibodies, whereas the cells of embryonal carcinoma are CD117-negative and CD30-positive.

In some rare seminomas, single tumor cells are cytokeratin- and CD 30-positive. OCT4 is typically positive in seminoma and embryonal carcinoma. Likewise, yolk sac tumor, spermatocytic seminoma, and choriocarcinoma are all OCT4 negative. Almost all seminomas (and cases of IGCNU) express podoplanin on the cytoplasmic membranes, whereas embryonal carcinomas are either negative or, in about 30 % of the cases, show limited reactivity that is restricted to the apical surfaces of the cells. SOX1 occurs in about 95 % of seminomas and is negative in embryonal carcinoma. CD 30 positive reactivity occurs in 93–100 % of embryonal carcinomas but the other germ cell tumors, including seminoma, are either negative or show only rare positive cells.

Rarely, these tumors are mistaken for lymphoma. This typically spread interstitially among the entrapped, atrophic seminiferous tubules.

4.2.4.4 Genetics

Seminomas are, without exception, aneuploid tumor with low copy number of i(12p).

4.2.4.5 Prognostic Factors

The most important prognostic factors are the diameter of the tumor and the invasion of the rete testis, whereas vascular invasion seems not to have the same prognostic importance as in NSGCT (Table 4.6)

Table 4.6

Prognostic factors predictive of metastasis in seminoma

Diameter >40 mm

Strong evidence

Age <30 years

Equivocal

Invasion of rete testis

Strong evidence

Vascular invasion

Equivocal

4.2.5 Spermatocytic Seminoma

It arises only in the male gonad and represents 1–4 % of seminomas. Patients are older (average 52 years) than those with other types of GCTs. Asynchronous bilateral occurrence is also more frequent (9 %) than in other TGCTs.

There are no racial differences or causal relationships with cryptorchidism.

4.2.5.1 Pathology

The cut surface is described as mucoid, gelatinous or edematous showing cystic, necrotic, and even hemorrhagic areas. The tumor tissue is yellowish or cream-colored, well circumscribed and can be multinodular. The tumor grows in an expansive and not infiltrative manner.

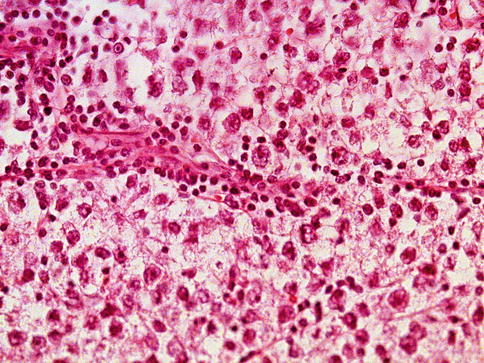

Microscopically, the tumor borders are sharp. Three different tumor cell types are present. The large (15–20 μm) cells with rather regular round nucleus predominate. The small cells (6–8 μm) resemble lymphocytes and the single scattered giant cells (50–150 μm). All have nuclei with a coarse chromatin.

Lymphocytes are scanty and in the neighboring tubules IGCNUs cells are missed. Intratubular spread of tumor cells is frequent. The polymorphous micromorphology with many mitotic figures gives the impression of an extremely aggressive tumor (Fig. 4.8, 4.9 and 4.10).

Fig. 4.8

Gross features of spermatocytic seminoma

Fig. 4.9

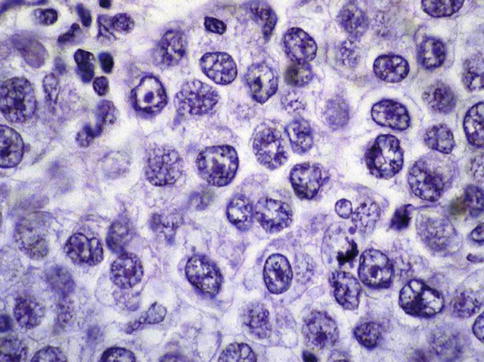

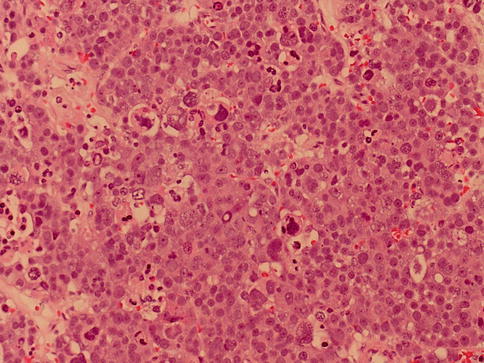

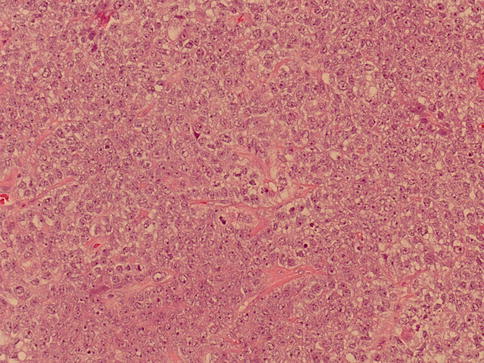

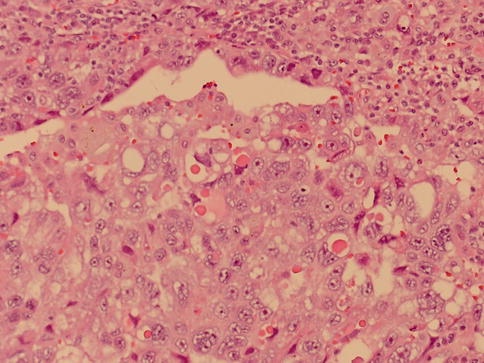

Microscopic features of spermatocytic seminoma

Fig. 4.10

Three cell type characteristic of spermatocytic seminoma

The so-called anaplastic spermatocytic seminoma contains a monomorphous population of large cells with big nucleoli that has no prognostic significance. Spermatocytic seminoma combined with sarcoma, mostly rhabdomyosarcoma, has been described and is a very aggressive disease.

4.2.5.2 Immunohistochemistry

The tumor cells are negative for all markers which are commonly found in GCTs. The PLAP reaction is, with very few exceptions, negative. Forty percent of spermatocytic seminomas are CD117+ and some few show a dot-like focal perinuclear reaction for low molecular-weight cytokeratin (CAM 5.2). Spermatocytic seminoma is OCT4 negative, a fact that can be used to differentiate from seminoma and embryonal carcinoma in selected cases, since both are positive.

4.2.5.3 Genetics

The tumor cells are polyploid or aneuploid. Gain of chromosome 9 combined with an unchanged chromosome 12 seems to be specific for this tumor.

4.2.5.4 Prognostic Factors

Usually these tumors are confined to the testis and never relapse and only rarely metastasize. The sarcoma component in mixed tumors metastasizes primarily to the lung and may be responsible of patient dead.

4.3 Non-seminomatous Germ Cell Tumors (NSGCTs)

4.3.1 Embryonal Carcinoma

The pure form of embryonal carcinoma (EC) accounts only for 2–10 % of all GCTs, but is very frequent (80 %) in mixed neoplasms with more than one germ cell component. The patients are on average 30 years old.

4.3.1.1 Pathology

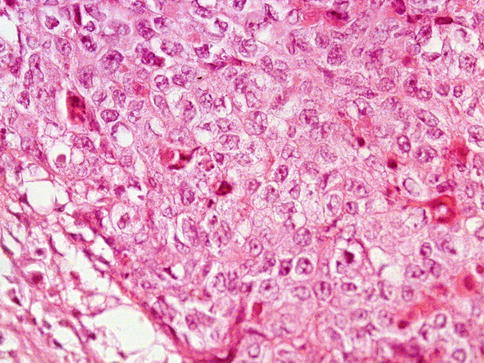

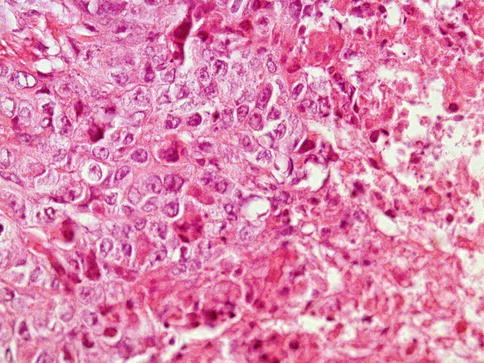

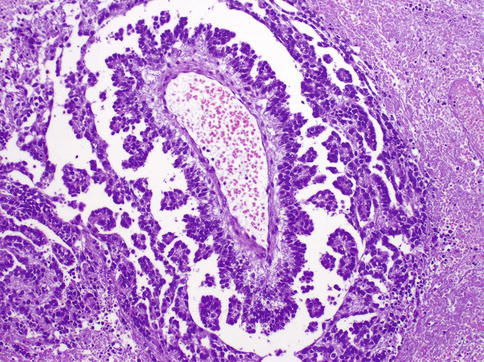

The tumors are usually small and the cut surface is granular. Necrosis and small hemorrhagic spots give the grayish colored tumor. The growth pattern can be solid, papillary, glandular, or tubular (predominant architectural pattern occupying at least 50 %). Less common primary patterns include nested, anastomosing glandular, micropapillary, sieve-like glandular, pseudopapillary, and blastocyst-like. Rarely, embryonal carcinoma develops in the context of polyembryoma-like (Fig. 4.11, 4.12, 4.13, 4.14, 4.15, 4.16, 4.17, 4.18 and 4.19).

Fig. 4.11

Gross features of embryonal carcinoma of the testes

Fig. 4.12

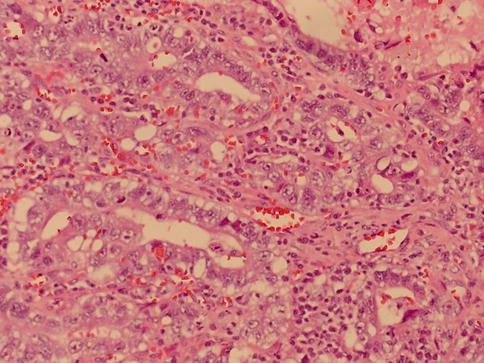

Embryonal carcinoma of the testes showing solid growth

Fig. 4.13

Embryonal carcinoma of the testes showing solid growth and focal tumor necrosis

Fig. 4.14

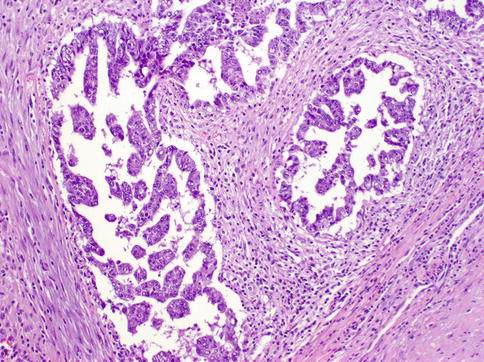

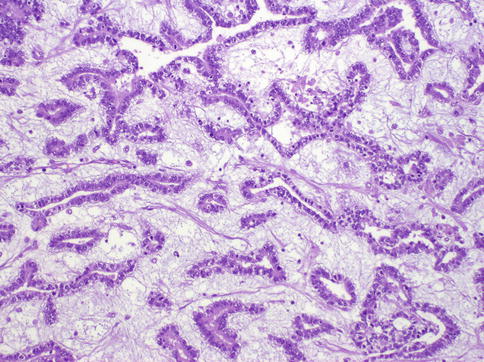

Embryonal carcinoma showing anastomosing glandular architecture

Fig. 4.15

Embryonal carcinoma showing glandular and micropapillary architecture

Fig. 4.16

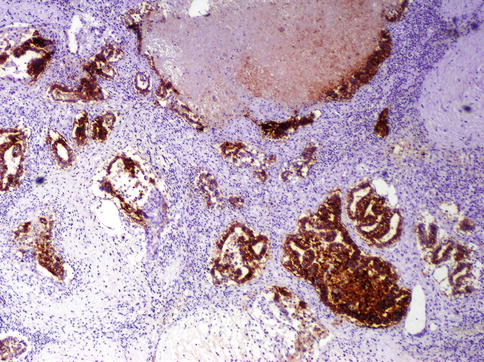

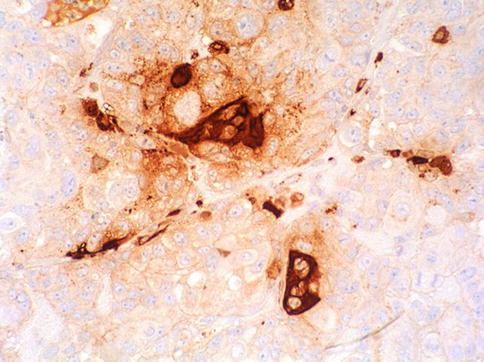

CD30 is positive in embryonal carcinoma

Fig. 4.17

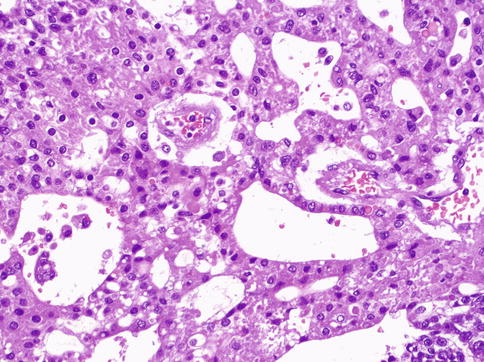

Embryonal carcinoma showing tubular architecture

Fig. 4.18

Tubular structures highlighted with anti-CD30 immunhistochemistry

Fig. 4.19

Embryonal carcinoma showing blastocyst-like features

Occasionally, EC may present significant chronic inflammation and granulomatous lesion suggesting seminoma. Also, features suggesting endodermal sinus tumor or teratoma may be seen.

The tumor cells are large primitive epithelial cells with a cytoplasm varying from amphophilic to basophilic or clear (seminoma-like cells). Finding intratubular spreading tumor masses with central necrosis is common.

The large pleomorphic and hypercromatic nuclei contain one or more large eosinophilic nucleoli. Mitoses are abundant. Syncytiotrophoblast giant cells may be present. Half of cases show vascular invasion.

4.3.1.2 Immunohistochemistry

The positive staining with cytokeratin antibodies (AE1/AE3; CAM 5.2) confirms the epithelial nature of these tumors. Unlike with seminomas, the PLAP reaction is only focally positive.

The strong and specific staining with CD 30 (Ki 1, Ber-H2) can lead to a wrong diagnosis of giant cell (immunoblastic) lymphoma. Nuclear expression of OCT4 and SALL4 is common in EC. As already mentioned, ECs are negative for CD 117, whereas seminomas do not react with cytokeratin antibodies and CD 30. SOX1 occurs in about 95 % of seminomas and is negative in embryonal carcinoma.

4.3.1.3 Genetics

The aneuploid or even triploid tumor cells show manifold chromosomal aberrations, most constant being the presence of i(12p). The number of i(12p) copies seems to correlate with the aggressiveness of the EC.

4.4 Yolk Sac Tumor

The pure form of yolk sac tumor (YST) is the most frequent (80 %) GCT of childhood. The average patient age is about 18 months, since most tumors arise in the first 2 years of life. In adults, YST is a frequent (40 %) component of mixed GCT, but rare in pure form.

4.4.1 Pathology

The tumor is not encapsulated and is yellow or white in color. Tissue consistency is usually soft, but can also be firm. Necrosis and hemorrhages are present, especially in large tumors of adults. Cystic changes are common.

The microscopic picture is that of a confusing variety of cells and patterns, but in sporadic cases the tumor is composed of one single cell type or only one histologic pattern.

Microcystic, papillary, and solid, spindle cell, and mucoid areas can alternate in the different parts of the tumor and produce a meshwork with spaces appearing to be empty or glandular and pseudoglandular structures (Figs. 4.20, 4.21, 4.22, 4.23, 4.24, 4.25, 4.26, 4.27, 4.28 and 4.29).

Fig. 4.20

Gross view of pure yolk sac tumor

Fig. 4.21

Solid growth pattern of yolk sac tumor

Fig. 4.22

Solid microscopic pattern of yolk sac tumor with hyaline globules

Fig. 4.23

Glandular pattern of yolk sac tumor

Fig. 4.24

Glandular pattern of yolk sac tumor with myxoid stroma

Fig. 4.25

Microcystic pattern of yolk sac tumor

Fig. 4.26

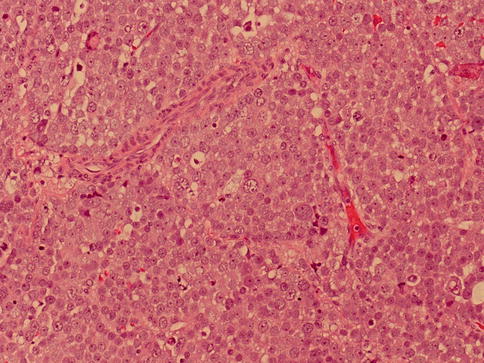

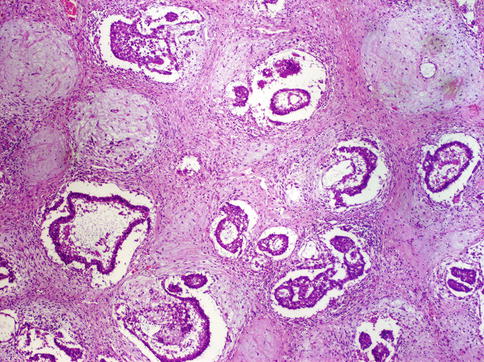

Hepatoid pattern of yolk sac tumor

Fig. 4.27

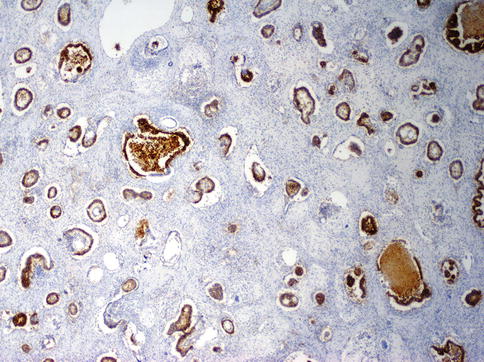

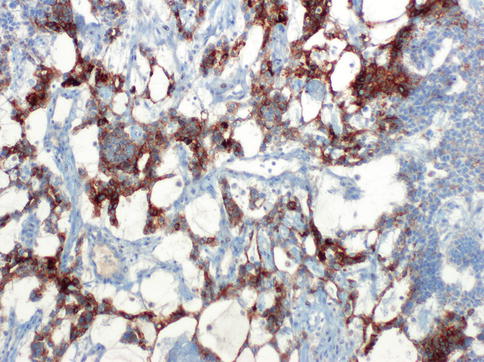

Glypican-3 expression in hepatoid yolk sac tumor

Fig. 4.28

Heppar-1 expression in hepatoid yolk sac tumor

Fig. 4.29

Schiller–Duval bodies in yolk sac tumor

Structures resembling yolk sac (vitelline) are not always present. Characteristic Schiller–Duval bodies simulate the endoderm with cuboidal cells covering a vascularized stalk of connective tissue. PAS+ (diastase-resistant) hyaline globules are common. Histologic growth patterns (Table 4.7) lack any clinical significance.

Table 4.7

Pathologic patterns of yolk sac tumor

Microcystic–reticular

Macrocystic

Papillary

Endodermal sinus

Solid pattern

Myxomatous

Glandular–alveolar

Sarcomatoid–spindle cell

Vitelline

Hepatoid

Parietal

4.4.2 Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemically all tumor cells react strongly positive with cytokeratin antibodies, and, unlike embryonal carcinoma, is negatively with CD 30. AFP is positive in 74–100 % of cases.

In children completely negative or patchy positive tumors can be observed. To avoid wrong diagnosis, awide sampling is advisable; also because AFP-positive tumor cells are encountered in one-third of ECs. Expression of SALL4 and glypican 3 but not OCT4 is characteristic of YST.

4.4.3 Genetics

Loss of 1p and 6q is rather typical for infantile YST.

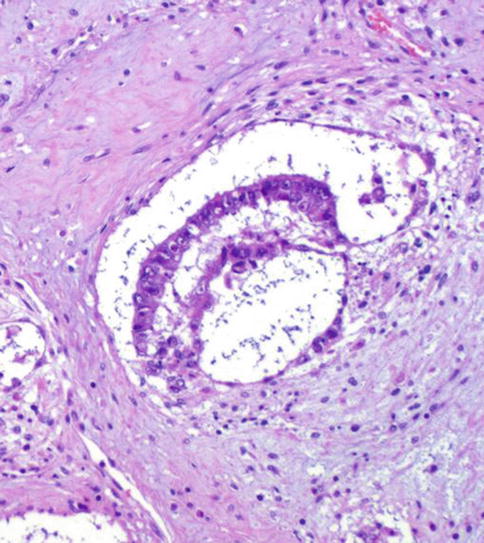

4.5 Polyembryoma

This tumor never occurs in pure form and invariably represents only a microscopically detectable structure, which is part of a NSGCT, frequently of a teratoma (Fig. 4.30).

Fig. 4.30

Histologic features of embryoid body in Polyembryoma

The ‘embryoid body’ roughly resembles a presomitic embryo of about 14 days old. The ‘embryoid bodies’ are embedded in a myxomatous stroma and rare among other components of NSGCT.

4.6 Choriocarcinoma and Other Types of Throphoblastic Neoplasia

Choriocarcinomas are the rarest GCT. The pure form accounts for less than 0.2 % of all GCTs.

The patients are young, with a peak incidence between 25 and 30 years, and about 70 % of patients have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis. Lung (100 %), liver (86 %), gastrointestinal tract (71 %), and brain (56 %) are the commonest, whereas the retroperitoneal lymph nodes are not involved.

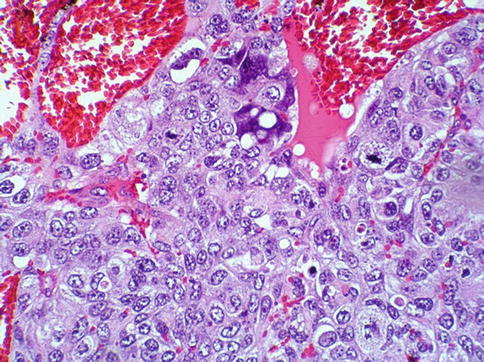

4.6.1 Pathology

Grossly the tumor is a small, hemorrhagic nodule sometimes surrounded by a rim of whitish preserved tumor tissue. The tumor masses are surrounded by blood and are located close to small vessels.

The tumor consists of three cellular components: the cytotrophoblast, the intermediate trophoblast, and the syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells, with cytotrophoblast being the most common cell and shows a water-clear cytoplasm; ‘intermediate trophoblast’ cells show more eosinophilic cytoplasm. The syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells lie on the surface of the cytotrophoblast (Figs. 4.31, 4.32 and 4.33).

Fig. 4.31

Gross features of choriocarcinoma of the testes showing necrosis and hemorrhage

Fig. 4.32

Microscopic features of choriocarcinoma

Fig. 4.33

Syncytiotrofoblast giant cells highlighted with anti-Β-HCG immunohistochemistry

4.6.2 Morphologic Variants

Monophasic choriocarcinoma are tumors composed only of cytotrophoblasts (p63 +) lacking the syncytiotrophoblast giant cells. Tumors made out of solely intermediate cytotrophoblasts (p63 −) are called, as in the uterus, placental site trophoblastic tumor.

Cystic trophoblastic variants have been described in metastatic sites post chemotherapy. Currently, it is regarded as variant of teratoma (Table 4.8).

Table 4.8

Cystic testicular lesions in childhood

Teratoma

Epidermoid cyst

Yolk sac tumor

Dermoid cyst

Ovarian type cystadenoma

Cystic lymphangioma

Juvenile granulosa cell tumor

Simple cysts

Cystic dysplasia of the rete testis

4.6.3 Immunohistochemistry

All types of cytotrophoblast react immunohistochemically with cytokeratin antibodies (CK 7, 8, 18, 19, CAM5.2, AE1/AE3) and with human placental lactogen.

Syncytiotrophoblast giant cells obviously react strongly positive with β-hCG antibodies, and also express epithelial membrane antigen and α-inhibin. OCT4 is negative in choriocarcinoma. Monophasic choriocarcinoma is positive for p63. PLAP is variable positive. Cytotrophoblast may be β-hCG negative. Placental site tumor may react with EMA.

4.6.4 Genetics

Some may exhibited the typical i(12p).

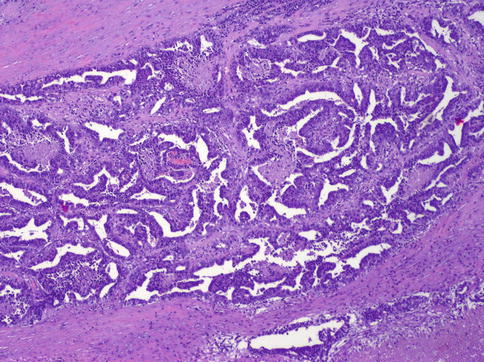

4.7 Teratoma

Teratomas are, after YST, the second most frequent (14–20 %) GCT in infancy, with an average age of 20 months. In adults pure teratomas account for 3–7 % of GCTs but they are a component in more than half of the mixed germ cell tumors (Table 4.8).

The tumor is benign in childhood, whereas in adults only epidermoid and dermoid cysts do not metastasize or relapse. In adults they are typically metastatic to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes

4.7.1 Pathology

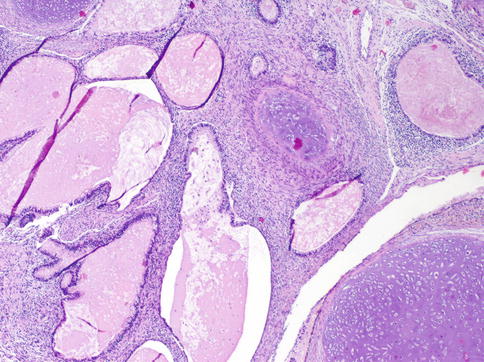

Composed of tissue components deriving from all three germinal layers–endo-, ecto-, and mesoderm. Thus, the gross morphology depends on the distribution and amount of single tumor components (Fig. 4.34).

Fig. 4.34

Microscopic features of testicular teratoma showing cartilaginous areas and small cysts lined by glandular epithelium

On the cut surface, glassy nodules representing cartilaginous areas, small cysts filled either with mucus or with laminated keratin, and pigmented areas can be recognized. In children the appearance is usually multicystic. Compared with other GCTs the consistency is always significantly more firm.

4.7.2 Variants

Mature teratomas contain cysts lined by squamous or glandular epithelium of enteric type or ciliated respiratory type epithelium, and cysts can be filled with mucus or keratin. Organoid structures mimicking gut or bronchous are made of the corresponding epithelium encircled by smooth muscle. Neuroendocrine cells may be present.

Mesodermal tissue is always represented by smooth muscle and mostly also by hyaline cartilage; bone with or without hematopoietic marrow is less common. Differentiated liver, prostate, pancreas, and thyroid are rarities Neuroglia with ependymal differentiation is also a rather common component. Pigmented retinal epithelium can occasionally be seen.

Immature teratomas contain an undifferentiated spindle cell mesenchymal stroma and small immature glands. Also the squamous epithelium is arranged in solid nests without keratinization. Other components are primitive neuroepithelium, renal blastema resembling Wilms tumor, rhabdomyoblasts, and fetal adipose tissue with lipoblasts.

Dermoid cyst consists of cysts lined by epidermis with skin, hair follicle, and sebaceous glands. This teratoma type is common in the ovary but remains extremely rare in the testis and some authors challenge it malignant potential.

Monodermal teratomas are those tumors in which a tissue component deriving from one germinal layer overgrows the other. The most frequent form is the primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET).

The most common monodermal differentiated tumor is the epidermoid cyst which accounts for 1 % of all intrascrotal tumors and can arise at any age. They have a thin whitish wall and are filled with horny material arranged in a laminated layer (onionskin-like).

The cyst is lined by an epidermis-like layer of squamous epithelium. Some authors regard the cyst as a teratoma only in cases when the surrounding testicular tissue presents IGCNU cells. Otherwise the cyst is considered to be a tumor-like lesion.

If a non-germ cell tumor arises from a somatic tissue component, it is classified as teratoma with somatic type malignancy. Such malignancies become clinically important only if the somatic malignancy reaches a field of view by low magnification (4× objective).

Sarcomas, in particular rhabdomyosarcoma, are the most common. But PNET tumors and squamous and adenocarcinomas have also been observed. Somatic type differentiation is seen in 4 % of patients with metastatic disease (Table 4.9).

Table 4.9

Somatic type malignancies seen in testicular teratoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma< div class='tao-gold-member'>Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access