Fig. 7.1

Laparoscopic trocar placement. Trocar placement plays a key role in facilitating laparoscopic procedures performed for pelvic prolapse and incontinence. Proper positioning of each trocar allows reach of the laparoscopic instruments from the deep pelvis up to the level of the sacrum as well as adequate articulation for suturing and knot-tying. Sufficient distance between trocars is necessary to prevent instrument crossing. For surgeries such as laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, which involves dissection over the sacrum and lower pelvis as well as extensive suturing of graft material to both regions, placement of at least four ports is usually necessary. Multiple port configurations are described in the literature. Placement of a 5- mm trocar is recommended in the umbilicus for the laparoscope, two ports placed 2 cm superior and medial to the anterior iliac spine on each side (typically a 10-mm port on the left and a 5- mm port on the right), and a 5-mm port placed in the midclavicular line at the level of the umbilicus on the side from which the surgeon will suture. The inferior epigastric vessels are the most commonly injured vessels at the time of lateral trocar placement [2]. Although these vessels are not easily visualized, placing the ports lateral to the rectus abdominis muscles usually ensures their avoidance. All trocars should be placed under direct visualization to avoid injury to the internal vasculature and surrounding soft tissues. When placing the initial port through the umbilicus, the table should be level to avoid injury to the greater vessels, and entry should be gained in the manner with which the surgeon is most comfortable. If the patient has a history of midline laparotomy or adhesions are expected, a left upper quadrant approach is recommended. After the entry site is inspected and the upper abdomen is surveyed, the patient should be placed in a steep Trendelenburg position to move the bowels cephalad for good visualization of the pelvis and for placement of the subsequent trocars (From Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography. Copyright © 2010–2013, with permission.)

7.3 Uterovaginal Prolapse Procedures

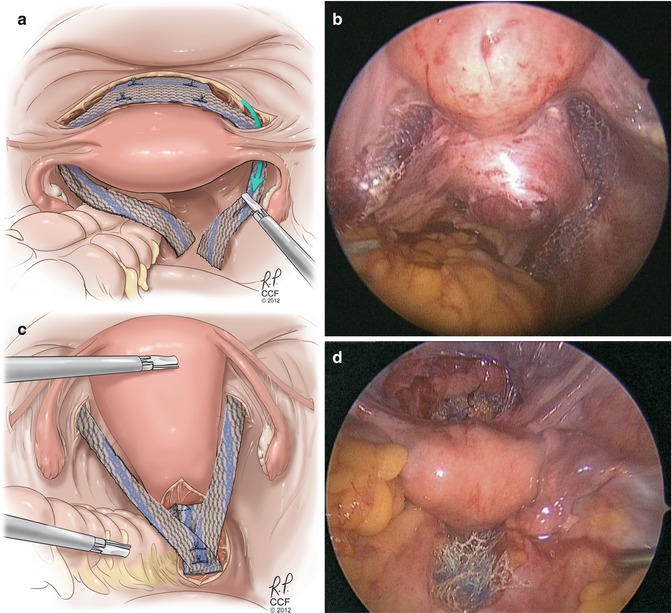

Fig. 7.2

Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension. Uterosacral ligament suspension is a procedure that is commonly performed at the time of hysterectomy for treatment of vaginal vault prolapse. The procedure involves attaching the vaginal vault to the midportion of the uterosacral ligament, which serves to restore the apical support of the vagina. When compared with the transvaginal approach, this type of suspension may decrease the risk of rectal and ureteral injury at the time of placement of the suspension sutures because these structures are easily identified in laparoscopic surgery [7]. Although laparoscopic uterosacral suspension after transvaginal hysterectomy is not very common, these benefits should be considered, especially if concomitant laparoscopic procedures are necessary. A laparoscopic approach can be taken at the time of laparoscopic hysterectomy, especially if no further vaginal reconstruction is needed at the end of the procedure. An Allis clamp can be used to elevate the vaginal cuff to delineate the uterosacral ligaments. Alternatively, a vaginal probe can be used to elevate the vagina, demarcating the uterosacral ligaments. Care is taken to avoid tenting the peritoneum close to the ureter on the ipsilateral side so as to not obstruct the ureter when the suspension sutures are tied down. A releasing peritoneal incision between the ligament and the ureter can be made in order to reduce peritoneal tension and subsequent ureteral kinking from suture placement. (a) A permanent or delayed absorbable suture is placed through the midportion of the uterosacral ligament (at the level of the ischial spine) with lateral to medial needle placement and then secured to the ipsilateral posterior and anterior vaginal cuffs. (b) One or two sutures can be placed on each side of the vagina, extracorporeal or intracorporeal knot-tying technique can be employed to suspend the vagina, (c) and the cuff is closed in an uninterrupted fashion

While there is sparse literature on outcomes from laparoscopic uterosacral ligament suspension because most studies do not follow patients beyond 2 years, the reported cure rate ranges from 76 to 90 % [8, 9]. Additionally, the laparoscopic approach has also been shown to have a lower risk of ureteral injury than transvaginal uterosacral suspension [7] and therefore may be a safe alternative to transvaginal surgery.

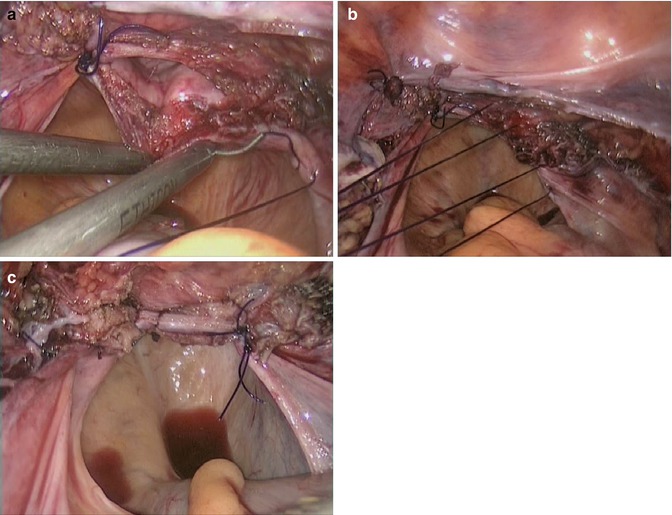

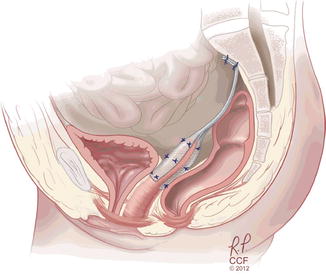

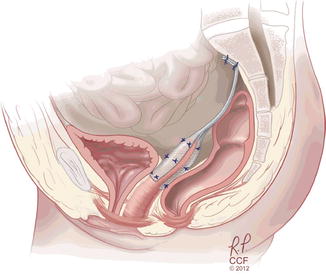

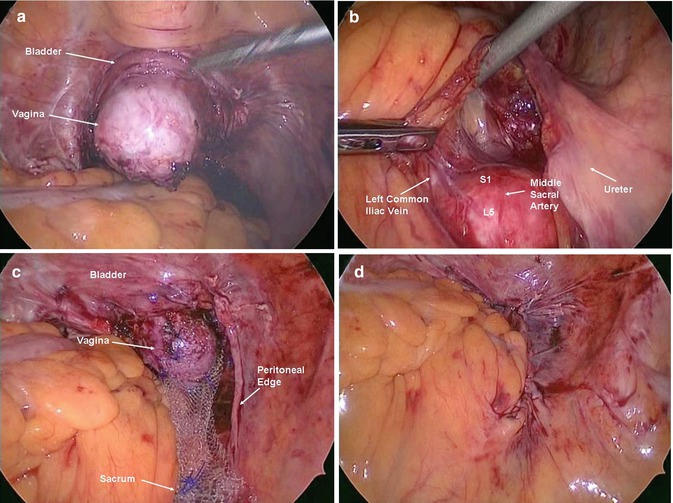

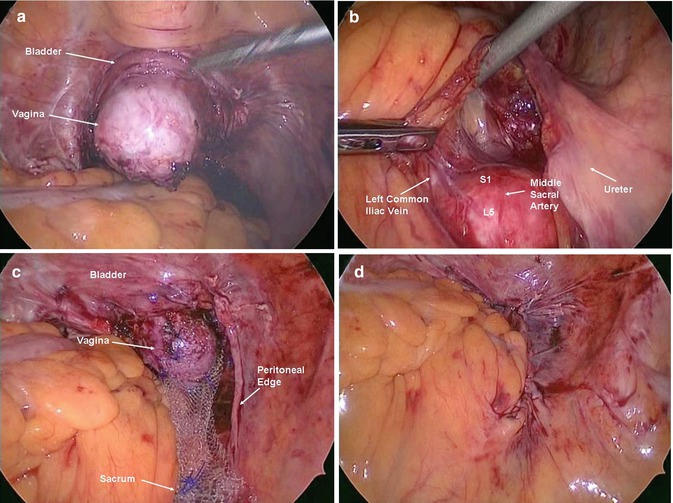

Fig. 7.3

Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy has become an alternative to open abdominal sacrocolpopexy for repair of vaginal vault prolapse. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy is considered the gold standard for vault prolapse and has demonstrated superior anatomic outcomes compared to transvaginal suspension procedures [10]; however, the operation is associated with a higher complication rate. A laparoscopic approach aims at bridging the gap between the advantages of vaginal surgery, namely, decreased morbidity and faster patient recovery, and the surgical success rates of abdominal sacrocolpopexy [10]. For young women who are sexually active with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, reconstruction with a sacrocolpopexy procedure is beneficial because the success rates are high because the procedure adequately restores normal pelvic anatomy and maintains vaginal length [11]. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy involves suspension of the vagina to the sacral promontory using a bridging graft that can be made of biologic or synthetic materials. The graft is sutured to the anterior as well as the posterior vagina and then to the anterior longitudinal ligament of the sacrum. We strongly believe that the minimally invasive approach to sacrocolpopexy should not have alterations from the open approach. The exact same steps, suture type and number, and graft should be used with open or laparoscopic surgery (From Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography. Copyright © 2012–2013, with permission)

Patient positioning is critical |

Place egg crate or other anti-slip device directly below patient to prevent movement during operation. |

Position buttocks slightly beyond end of table so that vaginal manipulation is possible. |

Both arms are tucked and protected. |

Once intra-abdominal access is gained, steep Trendelenburg positioning helps move the small bowel into the upper abdomen, |

Two knowledgeable assistants are necessary |

One works intra-abdominally and helps with retraction. |

One works vaginally and manipulates the vagina and rectum to optimize visualization. |

Side dock the robot, either parallel or at a 45-degree angle, to the table. |

Placement of ports is integral to procedure success. |

Ensure there is enough space between the robot arms to prevent collision. |

If the colon is redundant, an epiploica can be sutured temporarily to the left anterior abdominal wall to improve visualization. |

If hysterectomy is planned, a supracervical hysterectomy should be considered because the cervix may help to decrease future mesh erosions. Alternatively, a vaginal hysterectomy can be performed prior to a laparoscopic repair. |

Given the lack of tactile feedback in robotic surgery, identification of the sacral promontory can be challenging. Using laparoscopy initially, this area can be identified and marked with a cautery before docking the robot. |

Care should be taken to avoid the intervertebral disc while placing the sacral sutures. Deep stitches through the disc and periosteum should be avoided because cases of osteomyelitis have been reported after robotic sacrocolpopexy. |

A barbed suture can be used to close the peritoneum. |

Convert to laparotomy when necessary. Patient safety is of utmost importance |

The most commonly used material is a large-pore polypropylene mesh, which has proven to have fewer complications because of its favorable synthetic properties [11]. The technique of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy using graft placement begins with proper positioning of the patient in the low lithotomy position using Allen stirrups so that there is access to the vagina during the operation. A sponge stick or end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) sizer should be placed in the vagina for manipulation of the apex. A Foley catheter is placed in the bladder for continuous drainage throughout the operation. After intraperitoneal access is gained and laparoscopic trocars are placed, the small bowel should be gently placed into the upper abdomen and the sigmoid colon deviated to the left pelvis as much as possible. If manual retraction of the sigmoid colon is not adequate, a temporary suture can be placed through the epiploica of the colon, passed through a trocar on the left side of the patient, and clamped to the drapes, with removal of the suture at the end of the procedure. The ureters are identified bilaterally; it is important to note their location throughout the duration of the case. Attention is then turned to the sacrum, and the sacral promontory is identified so that the presacral space may be entered.

Fig. 7.4

(a) The important landmarks of the presacral space include the aortic bifurcation, the common and internal iliac vessels, the sigmoid colon, and the right ureter. Notably, the left common iliac vessel is located medial to the iliac artery and is particularly vulnerable to injury during this procedure, as are the internal iliac vessels, the right ureter, and the middle sacral artery. Once all structures are identified, a longitudinal peritoneal incision is made over the sacral promontory. Dissection is done carefully to reveal the bony promontory as well as the anterior longitudinal ligament, which will later serve as the attachment point for the graft. Approximately 4 cm of exposure is necessary, and this is achieved by using blunt dissection or electrocauterization of the subperitoneal fat. Caution should be taken to avoid the presacral venous plexus as well as the middle sacral vein and artery, which are often encountered during this dissection. Dissection caudally through the peritoneum and subperitoneal fat is carried down to the level of the posterior culde-sac. The rectum and right ureter are visualized at all times during this part of the procedure as the course of the dissection is located between these two structures. (b) The vagina is elevated cephalad using a sponge stick or EEA sizer, the peritoneum overlying the anterior vaginal apex is incised transversely, and the bladder is dissected off the anterior vagina using sharp dissection, creating a 4- to 5-cm pocket. If this plane is difficult to establish, the bladder can be filled in a retrograde fashion to find the correct dissection plane. Similarly, the peritoneum overlying the posterior vagina is incised, and dissection is done overlying the vagina and extending into the posterior cul-de-sac, creating a 4- to 5-cm pocket. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the rectum during this part of the surgery. If the rectum is hard to delineate, a second EEA sizer should be introduced into the rectum, and with manipulation of the vaginal and rectal EEA sizers, the correct dissection plane is identified. If the patient has concomitant defecatory dysfunction and/or rectal prolapse, the posterior dissection is sometimes carried down to the level of the perineal body. In most cases, however, the 4- to 5-cm pocket is sufficient. Once dissection is complete, the graft is prepared. A lightweight polypropylene mesh is currently most commonly used. The mesh is fashioned into two arms that are approximately 4 Å~ 15 cm in size. The graft is first attached to the posterior vaginal wall using 4–6 permanent or delayed-absorbable No. 0 or 2-0 sutures in an interrupted fashion, 1–2 cm apart from each other. Sutures are placed through the fibromuscular tissue of the vagina but not through the underlying epithelium. S1 1st sacral vertebral body, L5 5th lumbar vertebral body. (c) The graft extends approximately half-way down the posterior vaginal wall. The second arm of the graft is then attached to the anterior vaginal wall in a similar fashion. Delayed absorbable sutures should be used for the most distal stitches close to the bladder to avoid suture erosion and fistulization. The vagina is then elevated with the sponge stick or EEA sizer toward the sacral promontory. The graft is trimmed to the appropriate length and then sutured to the anterior longitudinal ligament using a stiff but small half-curved tapered needle with two to three permanent No. 0 monofilament sutures. (d) The peritoneum is then closed over the exposed graft with absorbable suture. After cystoscopy, a vaginal examination is performed, and a posterior colporrhaphy and perineorrhaphy are performed if needed

A review of abdominal sacrocolpopexy reported the success rate when defined as lack of apical vaginal prolapse postoperatively from 78 to 100 % [12]. The median reoperation rates for pelvic organ prolapse and for stress urinary incontinence in the studies that reported these outcomes were 4.4 % (range, 0–18.2 %) and 4.9 % (range, 1.2–30.9 %), respectively. A randomized, controlled trial of sacrocolpopexy with and without concomitant Burch colposuspension at 2-year follow-up had reassuring anatomic outcomes, with 95 % of subjects having excellent objective outcomes for the vaginal apex (within 2 cm of total vaginal length), with 2 % of subjects demonstrating stage III prolapse, and 3 % of subjects undergoing reoperation for prolapse [13]. These subjects also demonstrated improved urinary, defecatory, and sexual function based on validated questionnaires. Although most of the literature has been focused on abdominal sacrocolpopexy, there are emerging data on the laparoscopic approach. A comprehensive review looking at over 1,000 patients in 11 series who underwent laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy revealed that the conversion rates and operative times had decreased substantially with increased experience in performing this procedure [10]. The mean follow-up for these series was 24.6 months with an average patient satisfaction rate of 94.4 % and a 6.2 % prolapse reoperation rate [10]. From this review, the authors concluded that a laparoscopic approach to sacrocolpopexy upholds the outcomes of the gold standard of abdominal sacrocolpopexy and is a very good minimally invasive option for patients with vaginal vault prolapse [10].

7.3.1 Laparoscopic Hysteropexy

Hysterectomy is often done at the time of surgical repair for uterine and uterovaginal prolapse. Uterine preservation techniques have largely been employed in women with uterovaginal prolapse desiring future fertility. However, there has been a small shift in this practice as more women are requesting uterine preservation for other important reasons, including issues of sexuality, body image, cultural preferences, and the concern for earlier-onset menopause after hysterectomy [11]. The risk of unanticipated pathology in asymptomatic women remains low [14]; however, it is important to determine which patients are appropriate candidates for uterine-preserving surgery. Uterine-preserving surgery is contraindicated in women with a history of cervical dysplasia, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, postmenopausal bleeding, and risk factors for endometrial carcinoma. Additionally, women who choose to undergo hysteropexy should be counseled about the need for continued cancer surveillance and potential risks associated with future pregnancies [15].

Most procedures that aim to suspend the vaginal apex are performed in a similar fashion to those performed with hysterectomy, with some necessary modifications [11]. The minimally invasive abdominal procedures most commonly described in the literature include laparoscopic uterosacral ligament suspension and laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy. Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament suspension is performed similarly to vaginal vault suspension to the uterosacral ligaments. The uterus is suspended to a portion of the ligament on each side, preferably using permanent suture. Additionally, the uterosacral ligaments can be shortened with sutures, providing additional support. This procedure is favorable because it restores normal anatomy while preserving the uterus. Furthermore, it carries little risk for subsequent pregnancy and delivery. The only study to compare laparoscopic hysteropexy via uterosacral ligament suspension to vaginal hysterectomy with subsequent vaginal vault suspension is a retrospective cohort study of 50 patients [16]. The authors found that hysteropexy patients had better vault suspension as measured by the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification examination postoperatively and experienced fewer failures as measured by reoperation rates when compared to the vaginal vault suspension group [16].