Fig. 14.1

A sagittal view of the female pelvic floor. All measurements are taken with the vaginal orifice (hymen) as the midpoint with a value of 0. Points within the vaginal cavity are negative and points outside the vaginal cavity are positive (From Bump et al. [4]; with permission)

Table 14.1

Staging criteria for POP-Q

POP-Q staging criteria | |

|---|---|

Stage 0 | Aa, Ap, Ba, Bp = −3 and C or D ≤ − (tvl – 2) cm |

Stage I | Stage 0 criteria not met and leading <−1 cm |

Stage II | Leading edge ≥ −1 cm but ≤+1 cm |

Stage III | Leading edge > +1 cm but <+ (tvl – 2) cm |

Stage IV | Leading edge ≥ +(tvl – 2) cm |

14.2 Prolapse Quantification

In order to describe pelvic floor dysfunction as it relates to gynecology, an objective system to quantify prolapse has been developed [4]. As described in Fig. 14.1, the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system allows for a quick, one-line dissemination of the severity of pelvic organ prolapse, allowing the reader to understand the degree and type of prolapse (anterior versus posterior). Given this quantification system, a staging protocol, as described in Table 14.1, was concurrently developed.

14.3 Patient Care for Single-Port Pelvic Floor Repair

14.3.1 Preoperative

Women typically appear at the clinic with prolapse symptoms, which may include vaginal bulge, pelvic pain, sexual dysfunction (including dyspareunia), and urinary or fecal dysfunction. A standardized, comprehensive history that addresses prolapse, urinary, bowel, and sexual symptoms is completed. A physical examination, including assessment of the pelvic floor utilizing the POP-Q system, a cough test, and a Q-tip test are also performed. Perineal ultrasound analyzing detrusor and bladder neck caliber is carried out. The patient is further investigated with cystometric urodynamic studies, if indicated.

All patients are offered a vaginal support device to reduce vaginal bulge in the form of a ring pessary if they are sexually active or a mushroom pessary if they are not active. Conservative management is recommended initially for a minimum of 3–6 months and includes pelvic floor exercises, the use of estrogen cream if it is not contraindicated, lifestyle changes (including a reduction in caffeine intake and addressing constipation), reducing weight, reducing intra-abdominal pressure by decreasing heavy lifting (modifying gym activities such as lying down when lifting weights and increasing repetition with decreased load when lifting), and managing asthma or smoking (decreased coughing). Patients are advised to prolong the conservative management period until their family is complete. All patients are given bowel preparation the day before any laparoscopic pelvic floor surgery.

14.3.2 Consent Visit

If the patient’s symptoms persist and she desires surgical management, she is asked to speak with the surgeon and her partner or support person about the postoperative period. They are informed about intraoperative prolapse staging, where 29 % of prolapses are upgraded and 9 % are downgraded, and subsequent modifications to the surgery that may be made owing to intraoperative findings [5]. Patients are reminded that pelvic floor repair is a major operation requiring strict and lifelong lifestyle management postoperatively. They are told about the risks of mesh repair as well as the limited data on the use of mesh in gynecology. This is an important aspect of the treatment because women with active lifestyles are prone to organ prolapse and, because the procedure is relatively pain-free postoperatively, they may relapse and compromise successful outcomes. Hence, strict follow-up visits at 1 week for detection of early complications, then 6 weeks, 3, 6, and 12 months, and annually thereafter are required.

14.3.3 Postoperative

An indwelling catheter (IDC) and vaginal pack are inserted immediately after the operation and removed the next day. A deep vein thrombosis prevention protocol is followed, and laxative medication in the form of a bulking agent is administered. It is recommended that patients stay in the hospital until there is no significant postvoid residual (<20 %) and the bowels are active.

Good patient selection, sound surgical skills, and postoperative patient lifestyle changes are cornerstones of a successful pelvic floor repair surgery.

14.4 Instruments, Ergonomics, and Learning Curve

14.4.1 Instruments (Commonly Used in LESS Pelvic Floor Repair)

30-degree, 5-mm bariatric scopes or 5-mm flexible scopes (Olympus; Center Valley, PA)

Ligosure roticulating instruments (Covidien; Mansfield, MA)

Endostitch (Covidien; Mansfield, MA) with Ethibond sutures (Ethicon; Somerville, NJ) or a straight needle-holder utilizing V-loc (Covidien; Mansfield, MA)

Straight tooth and bowel graspers

Roticulating graspers

Smoke evacuator

Suction irrigation

Covidien (Mansfield, MA) or GelPOINT single-port surgical device (Applied Medical; Rancho Santa Margarita, CA)

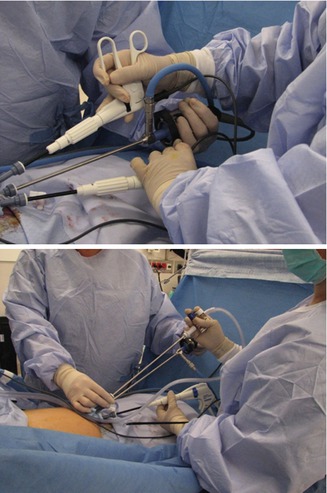

Fig. 14.2

Proper ergonomics are vitally important in a LESS procedure. Because of the single port access to the intra-abdominal cavity, the degrees of freedom are limited compared to those in conventional multiport laparoscopy. A surgical plan taking into account these limitations is important in producing successful outcomes for LESS pelvic floor repair. Note how the surgeons are standing as midline as possible with their arms in neutral positions and bodies facing away from the patient’s head

14.4.2 Ergonomics

When using single-site ports of any kind, the ergonomics of the instruments will become crucial in performing the surgery. There are two important points regarding ergonomics in LESS pelvic floor repair. First, the operation can be cumbersome if a proper approach has not been thought through owing to the single fulcrum point at the abdomen as well as crowding of the instruments (Fig. 14.2). Second, there are issues regarding the body positioning of the surgeon and the assistant.

Unlike conventional laparoscopy in which crossing of instruments is discouraged, such a maneuver becomes necessary at times in LESS. Crossing instruments is safe because of the insulating properties of roticulating graspers. This requires retraining for many conventional laparoscopic surgeons. Furthermore, the surgeon needs to be aware of possible instrument crowding issues. Thus, in order to minimize surgery time as well as reduce frustration, the surgeon needs to plan out the order and positioning of the instruments, taking into account the patient’s anatomy, body mass index (BMI), and any surgical procedures performed previously on this patient prior to making an incision.

The operation is easier if a 5-mm bariatric 30° scope is used with a highly experienced assistant who will need to have both hands constantly on the camera and light lead to provide the best possible view. It is advisable to commence with the scope on the right side or most cephalic channel to enable the assistant to push the camera down toward the patient and away from the midline. The surgeon should place the instruments in a way that is physically most comfortable. As the operation proceeds, changing the channels of the instruments or changing the operating side may be required; therefore the surgeon should stand as close as possible to the head of the patient and in the midline. This provides the most accessible plane for operating on the pelvic floor. This is a particularly important point in LESS gynecology because of the limited degrees of freedom with a single-port approach and subsequent problems with needing to lean over patients (Fig. 14.2).

14.4.3 Learning Curve

A short learning curve for LESS requires sound anatomic knowledge, conventional laparoscopic surgical experience, and proficiency with laparoscopic suturing. Furthermore, an understanding of current surgical procedures for pelvic floor repair is highly valued, since the approaches to these do not change significantly with the transabdominal approach (LESS versus multiport laparoscopy).

With regard to LESS versus conventional laparoscopic transabdominal pelvic floor repair surgeries, it has been noted that LESS takes more time (which decreases with experience) and is more strenuous if the ergonomics of the patient or operator have not been properly thought through. Current data are only available as case reports; however, the data from these reports appear encouraging both for patients and for surgeons [6]. This is probably because the surgeries themselves are the same, but the approach to them is simply being modified (single-port) in order to improve cosmesis and minimize invasiveness. Thus, the learning curve for a surgeon when training in LESS mainly deals with port insertion and ergonomics.

Prior to utilizing a LESS approach, as occurred with this chapter’s first author, it is beneficial to have advanced skills in conventional laparoscopic pelvic floor repair surgeries utilizing Verress needles to establish the pneumoperitoneum. When switching to LESS, the author required approximately ten port insertions with the Covidien device (Mansfield, MA) in order to demonstrate efficiency and accuracy in the port insertion technique. This was achieved in dry laboratories, animal laboratories, and in the operating theater under supervision. Subsequently, the insertion of the GelPOINT port (Applied Medical; Rancho Santa Margarita, CA) required only one practice insertion with instruction in order to achieve proficiency. This was achieved following approximately 200 LESS procedures utilizing Covidien ports. Initially, port insertion took 7–10 min, but with practice (~25 procedures), this decreased to approximately 3–4 min per insertion.

14.5 Establishing the Pneumoperitoneum and Inserting the Port

14.5.1 Covidien SILS Port

All pelvic floor repair LESS procedures are performed under general anesthesia with the patient in the lithotomy position. Once the patient is prepared and draped, a periumbilical nerve block is performed by injecting 5 mL of 0.5 % bupivicaine and adrenaline at each of the 3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock positions. A 15–20-mm vertical transumbilical skin incision is made. The rectus sheath is grasped with two graspers and a sharp incision made through the fascia with the tip of a scalpel, allowing intraperitoneal access. The incision is stretched with an artery clip and opened to its maximum opening width, which should accommodate the insertion of two S-retractors. A scalpel is used to extend the sheath incision to 2.5 cm under the skin without extending the skin incision.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree