Fig. 14.1

Multiple Randall’s plaques in the papilla (black arrow)

This hole in the urinary tract is where the pelvis of the kidney joins the ureter, called the UPJ, or ureteral pelvic juncture (Fig. 14.2). This is the first anatomical narrowing of the urinary tract. Here, stones can get trapped and block the flow of urine from the renal pelvis into the ureter. This interruption of flow results in the back up of urine into the kidney. This causes the kidney to swell, or properly termed hydronephrosis. Hydronephrosis can be graded as mild, moderate or severe, depending on how swollen the kidney becomes. Ultimately, the back of urine in the kidney can cause this intractable pain, referred to as flank pain or renal colic. This is the typical pain that brings a patient to the ER for treatment. Left untreated, the back up of urine may become infected, resulting in a kidney infection, also referred to as pyelonephritis.

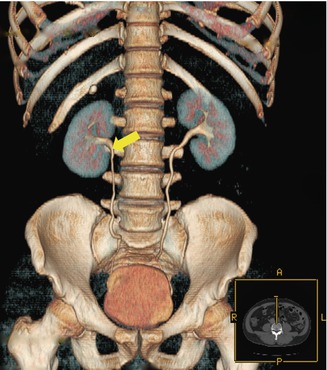

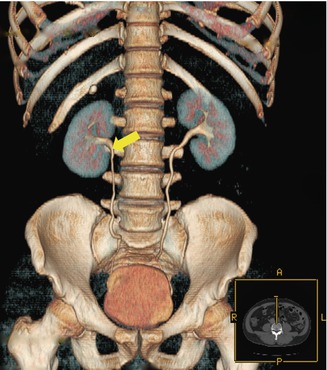

Fig. 14.2

3D CT Scan reconstruction of the urinary tract. The ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) is identified (yellow arrow)

Straight to the Point

Now that this stone is in the UPJ, the stone has several fates:

1.

It can remain where it is. This is the typical scenario that if the stone does not move and it continues to obstruct the ureter and there is progressive hydronephrosis, surgical intervention is typically required. This is the typical patient that goes to the ER where the patient may require urinary diversion with a stent or nephrostomy tube.

2.

It can continue forward into a deeper portion of the ureter toward the bladder. If the stone is small enough, it may advance further down the ureter, also referred to antegrade progression. If fortunate enough, the stone may advance down to the bladder and voided out with urination. The ureter has two other narrowed points where the stone can become blocked. The stone may get stuck at the level where the ureter crosses the iliac vessels or in the lowest point of the ureter, referred to as the UVJ, or ureteral pelvic juncture.

3.

It can propel backwards into the renal pelvis. The stone moving back into the kidney is called retrograde movement. In this last scenario, the stone has the potential to bounce back and forth between the kidney and ureter. This is what is I refer to as the “ping pong” effect. The stone bounces back and forth from the renal pelvis to the ureter, and then back again. When the stone bounces back into the renal pelvis, the pain typically resolves as the obstruction is relieved and urine is able to pass the stone down the ureter into the bladder and ultimately through the urethra. Upon entering and obstructing the ureter again, there is back of urine within the kidney, causing hydronephrosis and the flank pain can return.

The Point of No Return

There is a point of no return. The stone has migrated down the ureter where the stone is distal enough not to bounce back to kidney. As the stone moves down the ureter, the flank pain can begin to radiate down to the groin. As the stone approaches the bladder, the symptoms begin to change. The stone moves into the ureter that traverses the bladder, called the intramural ureter. The stone in this location results in irritation to bladder muscle, resulting in irritative voiding symptoms, including frequency or urination, urgency of urination and even urge incontinence. Patients may also have burning with urination, or dysuria. These symptoms are very similar to symptoms of a UTI, however, the urine culture is typically negative for an infection.

Point Well Taken

Stone in the ureteral portion of the bladder presents differently in men and women. In men, the pain in the bladder can radiate to the testicle on the same side, referred to as the ipsilateral testicle. In women, the pain may be referred to the ipsilateral labia or possible pain within the vagina. I tell my patients that the objective interpretation of pain in this location is that this is a pending stone for passage since the stone is in it’s most distal location before entering the bladder.

In both men and women, a stone in the distal ureter needs to be differentiated from other disease processes, also called the differential diagnosis. Pain presenting in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen needs to be differentiated from appendicitis. Pain in the left lower quadrant should be differentiated from diverticulitis. Refer to your primary care physician or urologist who can do the appropriate examination and testing to make this differentiation and appropriate diagnosis.

The Point of the Matter

Most episodes of acute flank pain will be related to the kidney in origin. However, one must be aware of factors that can cause colic-like symptoms. This pain may be muscle-skeletal in origin. Pre-dating the onset of pain, patients may recall lifting or pulling something heavy that results in sharp flank pain that mimics pain associated with a stone. To differentiate stone pain from muscle skeletal pain, I ask patients to do a simple test. Placing your hands on your flank, rotate from side to side and from front to back. If the pain proves to be worse in one position and relieved in another, there is a good chance that this pain is muscle-skeletal in origin. If this pain displayed presents with the same intensity on the affected side regardless of the position they are in, this could represent pain that is renal in nature.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree