1. Respect the dignity of both patient and caregivers

2. Be sensitive to and respectful of the patient’s and family’s wishes

3. Use the most appropriate measures that are consistent with the choices of the patient or the patient’s legal surrogate

4. Ensure alleviation of pain and management of other physical symptoms

5. Recognize, assess, and address psychological, social, and spiritual problems

6. Ensure appropriate continuity of care by the patient’s primary and/or specialist physician

7. Provide access to therapies that may realistically be expected to improve the patient’s quality of life

8. Provide access to appropriate palliative care and hospice care

9. Respect the patient’s right to refuse treatment

10. Recognize the physician’s responsibility to forego treatments that are futile

Definition

Inconsistent definitions of palliative surgery have made comparing research results difficult, and clinical guidelines have suffered from blurred interpretations [10, 11]. Palliative surgery is defined as any invasive procedure in which the main intention is to mitigate physical symptoms in patients with incurable disease without causing premature death [12]. Accordingly, surgical palliative care comprises the complete spectrum from conventional open surgery to minimally invasive techniques such as endoscopic or percutaneous interventional radiological procedures (Table 25.2). In this context, the traditional limits of surgery are blurred, which underlines the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to the palliative patient. Palliative surgical procedures may include treatment of the tumour, such as bowel resection due to cancer in the presence of incurable distant metastases, which may relieve symptoms and prolong life. However, the treatment of symptoms is the main focus of palliative surgery. The distinction with regard to incomplete tumour resection (e.g. R2 resection) in patients surgically treated with curative intent is important. An operation with primarily curative intent that results in incomplete removal of the tumour and without a main focus on symptom relief is better categorised as non-curative surgery [13].

Table 25.2

Examples of interventions, which might be considered for palliative treatment of symptoms in patients with incurable disease

Technique | Example of indication |

|---|---|

Conventional open surgery | Bowel resection for obstruction or bleeding |

Laparoscopic surgery | Bowel resection, creation of ostomy |

Endoscopic surgery | |

Transanal endoscopic surgery (TEM) | Local resection of rectal tumour |

Self-expanding metal stent | Bowel obstruction, icterus |

Argon plasma coagulation | Tumour reduction, bleeding |

Interventional radiology | |

Percutaneous drainage | Fluid collections |

Stenting procedures | Common bile duct |

Endovascular procedures | Embolization |

The Scientific Evidence for Palliative Surgery

The scientific literature on this topic is complicated by numerous retrospective studies, often with small and heterogeneous study populations and ill-defined end points. In addition, validated QoL instruments have been employed only sporadically [14]. Because of various practical and ethical aspects related to clinical research on this group of patients, prospective randomised controlled trials (RCT) used to be the exception [12]. Accordingly, the lack of scientific evidence is a concern when many important clinical questions are addressed. The everyday clinical practice of palliative surgery has probably been guided more by the surgeons’ personal experience and traditions in many institutions, rather than true scientific evidence. Nevertheless, results from some well-designed prospective (randomised) studies or systematic reviews have provided useful and reliable clinical information, such as celiac plexus block in patients with non-resectable pancreatic cancer [15], the treatment of asymptomatic colorectal cancer with non-resectable synchronous colorectal metastases [16], and palliative relief of gastric outlet syndrome [14, 17]. Yet, the appropriate and timely clinical implementation of this knowledge remains a challenge in many institutions.

Research and Outcome Measures

In modern medicine, treatment effects are evaluated by outcome measures, which are often defined by the treatment provider, i.e. the physician. Common outcome measures to describe the effectiveness of the chosen treatment mostly include postoperative mortality and morbidity, disease-free cancer-specific or overall survival, response rates, and cure rates. Notably, none of these variables are suitable for evaluating QoL. Optimally, the goal of palliative surgery is to meet the patient’s individual needs and expectations [18]. Consequently, the effects of palliative treatment should be evaluated by individual outcome measures. Patients, relatives, and doctors tend to estimate QoL and treatment effects differently because doctors are biased by the wish to help and, necessarily, by judging the clinical situation and treatment effects from their own perspective [19, 20].

Various validated tools are available to measure QoL and assess symptoms. Spitzer et al. [21] published the Quality of Life Index in 1981, which is based on a physician-rated 5-item scale. Another used physician-rated score in widespread use is the ECOG Performance Status [22], which is mainly based on the patient’s ability to participate in daily life activities. Though these scores are helpful to describe the patient’s functional state and fitness, they are unsuitable for measuring the QoL for an individual patient.

The most used symptom score for palliative patients is the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) [23]. This score is based on ten frequent symptoms, including nausea, pain, appetite, and depression, and is a very useful tool for detecting common symptoms and to monitor the effects of treatment by repeated measurements. Also, a number of organ-specific QoL scores are available, including the 36-item Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index for gastrointestinal disorders [24].

More sophisticated QoL scores are available from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). The EORTC QoL-C30 is one of the most frequently used tools for QoL assessment in cancer research [25], with various organ-specific modules available. The scores are validated and translated into numerous languages. Another widespread general tool for QoL assessment is the Medical Outcomes Survey-Short Form (MOS-SF 36) [26].

Nevertheless, quantitative outcome measures, such as survival, are of importance in palliative care as they provide information on the prognostication of a disease. Prognostic information, though limited to subgroups of patients and never to an individual patient, is helpful for counselling patients and their relatives and plays a role when the indications of palliative procedures are contemplated.

Approach to the Palliative Surgical Patient

Palliative patients suffering from an incurable disease, and regarded to be in a hopeless situation, belong to a vulnerable group of individuals. Visiting with these patients and their relatives might be a challenge for many clinicians, which relates to their own emotions, being unable to offer a cure, and the fear of taking any hope away from the patient. Sound principles of surgical palliative care have been described extensively by Krouse et al. [6] (Table 25.1). These principles are based on effective and empathic communication with the patient and his or her family and respect for dignity and patient autonomy. With these principles in mind, the surgeon has extended his communication tools to deal with the palliative surgical patient and his or her family more appropriately, which also includes an emphatic and human contribution to optimised end-of-life care.

Establishing Indications

The feasibility of an operation is not an indication of its performance.

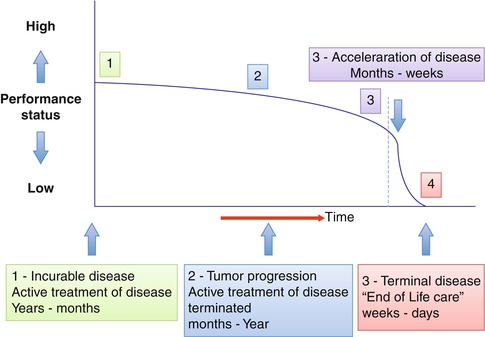

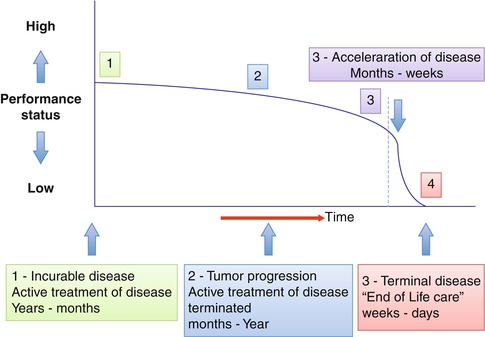

The aim of palliative surgery is to improve QoL. Therefore, indications for palliative surgical procedures depend strongly on the suggested benefit for the patient and anticipated relief of symptoms after intervention. Identifying individual treatment goals for the patient is the first prerequisite in this process. Treatment goals depend on the extent of disease, predominant co-morbidity, patient age, social and psychological context, and spiritual thoughts and wishes. Furthermore, where the patient is in the trajectory of the disease is important to take into account (Fig. 25.1). More complex procedures may be warranted in a younger and fit patient when the diagnosis of incurable cancer is established (Fig. 25.1, Phase 1) in order to achieve local tumour control and prevent the development of symptoms in the later course of the disease. This approach may not be the case for older and more fragile patients. Surgical procedures are usually not indicated in patients with rapidly deteriorating conditions who have a short life expectancy (Fig. 25.1, Phase 3 or 4).

Fig. 25.1

Disease trajectory of patients with incurable malignant disease. Intensity and type of treatment has to be defined according to performance status of the patient during the disease trajectory

The indications for palliative procedures may be coloured by aspects or needs other than pure medical factors. Both health-care providers and relatives may feel an urgent need that “something should be done” for a suffering patient. However, all chosen measures have to be in accordance with the patient’s expectations, wishes, and individual treatment goals; otherwise, those actions are useless and outside the context of appropriate palliative care. In addition, such motivations may threaten the patient’s dignity and autonomy. The dignity and autonomy of the patient are main principles of palliative care, and doctors are obliged to discourage any paternalistic interventions that may result in futile procedures with increased morbidity or mortality. The effects of any intervention are based on physical changes in the body and cannot be easily reversed. Accordingly, any complication in this context is a serious event that would most likely jeopardise the QoL and, thus, causing disastrous consequences for the remaining life of the patient: Above all, do no harm.

Communication

The crucial basis of good communication is a common understanding of the issue in question by the involved participants, i.e. the patient, the patient’s surrogate(s), and the surgeon. Achieving a common understanding of the underlying problems for the palliative surgical patient is the cornerstone of appropriate symptom management. This approach is not specific for palliative care, but common to any field of medicine. It is widely accepted, and even regulated by the legislation in most countries, that all communication with patients be based on full disclosure. Nowadays, rather than being passive recipients of medical care, patients are active participants. However, most doctors may perceive this communication as particularly difficult when they have to break bad news on dismal prognoses. Many surgeons find themselves in such a situation rather frequently, including settings other than cancer (e.g. trauma surgery). Successful communication depends heavily on personal skills but is also a matter of education and training.

Bradley et al. [27] recently defined four areas of end-of-life issues in surgical practice:

1.

The preoperative visit

2.

Discussing a poor prognosis

3.

Adverse outcome due to error

4.

Discussing death

During the preoperative visit, counselling with regard to the medical facts, is only one, albeit important, aspect among others. This is an important opportunity for establishing confidence between the patient, family, and doctor. Confidence is obtained from information based on full disclosure with an attitude of empathy. Empathy means being open to the patient’s thoughts and emotions and should not be confused with sympathy (i.e. to share the patient’s thoughts and emotions).

Exploring the patient’s understanding of his or her position and the treatment goals is one of the most important objectives. Open-ended questions are considered to be the most appropriate, as well as ensuring that the patient is the focus of the conversation. One other important goal is to discuss the need for advance directives, such as the use of ICU facilities or “Do not resuscitate” orders. Doctors may be reluctant to discuss these issues, but most patients appreciate reaching a common understanding on these issues of greatest importance from an end-of-life perspective [28]. Many difficult situations can be avoided if unintended complications or events occur and these aspects have been addressed properly before any intervention.

When palliative interventions are discussed, informing the patient and family of the intention of treatment and the possible outcomes is elementary. Making sure that patients do not misinterpret a palliative intervention as an opportunity to be cured is important. The patient should also be appropriately informed about possible unfavourable aspects associated with any intervention.

Breaking bad news may be one of the greatest challenges, and every surgeon will encounter this regularly in all fields of surgery. Maguire [29] suggested guidelines and strategies for dealing with this situation. In this process, the patients will appreciate openness and honesty, which are important tools for an empathic approach. Knowing which information has been shared with the patient already, how much information the patient wishes and, finally, choosing the appropriate terms are also important. An empathic approach does not exclude information in direct terms; to the contrary, patients demand the truth and will disclose any modifications of it. Honesty and openness, together with the affirmation of a continued will to be engaged, will build up the base for new hope rather than to take hope [6].

Adverse outcomes of interventions are an inherent part of any interventional discipline. Treatment failure may be related to insufficient preoperative investigations, wrong indications, failure to perform the procedure correctly, or other complications and circumstances beyond the surgeon’s control. Most of the aspects addressed with regard to breaking bad news also apply to this situation. However, when the aim of treatment is to improve the patient’s QoL, treatment failure may be perceived as being extremely disastrous for all those involved. Any preoperative efforts to establish a relationship based on mutual confidence would be of greatest importance when things go wrong. Evidence suggests that open disclosure of failures prevents, rather than stimulates, litigation, particularly when the responsible clinician takes the initiative to inform the patient [30]. Patients and surrogates expect an apology from the responsible doctor in most cases, and it is important to meet this desire [31].

Death, and talking about death, may be the point where the doctor reaches deepest into the patient’s life and his or her family within the end-of-life care. Death and dying will be an important issue not only when death occurs. This topic may be taken into consideration and drawn to attention by some patients when the bad news about a serious disease or the dismal prognosis is communicated, or even before a planned operation. The circumstances and the way of sharing this message with the patient and their family are of great importance for coping with the death of a family member. This is true both at the time of death and during the following grieving process.

Clinical Scenarios

Consistent with the uniform treatment goal of curative cancer treatment, i.e. the radical removal of all cancer tissue, uniform guidelines for reaching this goal are based on accumulated evidence. However, in the palliative setting, the identification of the individual treatment goal has to be followed by an individualised route for each patient to reach his or her aims. In illustrative terms, the process of palliative surgical care does not follow the broad highways of guidelines for curative cancer treatment, but rather a twisting narrow path through an unknown landscape. On this path, applying the philosophy of palliative care in clinical decision-making is the most important tool for reaching the destination safely. In other words, the identification and communication of the realistic treatment goals of the individual patient are based on maintaining the patient’s autonomy, dignity, and respect. This approach is fundamental to enabling an appropriate treatment plan for achieving the highest possible QoL.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree