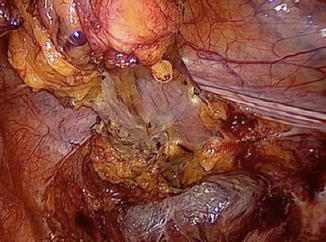

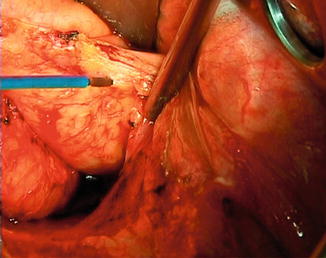

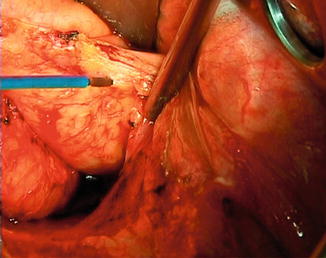

Fig. 4.1

Carcinoma threatening the mesorectal fascia on the left

Total Mesorectal Excision (TME) Current Controversies

TME is the key surgical objective [1–19]—can it however be achieved as well or better by laparoscopy, or by the da Vinci robot? When truly necessary, can the poor results so often obtained by the ‘standard’ APE be improved upon by superior access—e.g. the Kocher–Holm position face down with excision of the coccyx? All these are controversial issues (Fig. 4.2).

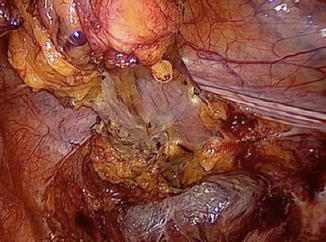

Fig. 4.2

A near perfect TME specimen (PO Nystrom)

Current priorities include better visualisation and more precise dissection, improved haemostasis and less collateral damage by diathermy (e.g. the use of TriVerse monopolar and LigaSure bipolar electricity). Gradually, surgeons, open, laparoscopic and robotic, are learning to recognise all the components of the autonomic nervous system of the pelvis which surround the TME. Indeed, surgeons are rewriting the anatomy books as surgical technology advances. The preservation of these crucial nerves depends a great part of human happiness and dignity.

There are few branches of surgery where care and effort in the craft of surgery yield so much benefit to our patients or where surgical anatomy is so important and advancing so rapidly.

Objectives

These are cure of cancer, local control of a disease where local failure causes great misery, keeping permanent stomas to a minimum and avoidance of collateral damage’. As a basic principle of any cancer operation, the block of tissue to be removed should be precisely defined and subjected to scrutiny by an independent pathologist. Thus, surgical anatomy and histopathologic audit should become exact sciences in their own right and surgical practice refined to include meaningful judgement of the oncologic quality of the specimen. It is rewarding to report that naked-eye evaluation of the excised specimen has become mandatory in Germany. Our own teaching workshops always emphasise the importance of ‘specimen-orientated surgeons’—i.e. surgeons whose first priority during the procedure is the quality of the fascial-covered untorn envelope of tissue that constitutes an optimal TME specimen.

Definition of the Rectum Itself

Unfortunately, this varies across the world, and all actual definitions are inherently unsatisfactory. For simplicity, we choose arbitrarily to define it as the bowel up to 15 cm above the anal verge (patient conscious). The low rectum is also arbitrarily defined as up to 6 cm, the mid as 6–12 and the upper as 12–15 cm.

Partial Mesorectal Excision (PME)

Height measurement, by general agreement, is from the anal verge in the conscious patient using a rigid sigmoidoscope. In the new world of MRI, the MRI height should also be recorded, and there is an argument for considering as truly ‘low’ cancers extending below the origins of the levator muscles on the coronal slice. Heights measured under anaesthesia need to be from the dentate line since the external sphincter dilates and retracts (add about 1.5 cm). Care is necessary: any instrument can push a mobile tumour up; flexible ones often give falsely high measurement. With these qualifications, it can be said that, in our view, most cancers with the lower edge at or below 12 cm should have TME as the key component of a radical cancer operation because the mesorectum is the primary field of lymphovascular spread (Fig. 4.3).

Fig. 4.3

The pelvis after laparoscopic PME

The decision as to whether the smaller partial mesorectal excision is adequate is finally confirmed after the mobilisation has been completed to the point where the mesorectum must be liberated from the adherent inferior hypogastric plexus—the region is usually referred to as the ‘lateral ligament’. It has long been convention and a very sound rule, borrowed from German surgical practice, that a minimum of 5 cm of mesentery should always be excised both proximal and distal to any colorectal cancer. Whilst lowering of muscle tube margin may safely be reduced to 1 cm in the interest of anal conservation, we have always believed that if less than a total mesorectal excision for a high tumour is contemplated, a minimum of 5 cm of the mesorectum distal to the lower edge of the cancer must be dissected in the perimesorectal (holy) plane. If, therefore, after initial mobilisation there is a clear 5 cm of mesorectum, then tapering into the mesentery, in the interest of making a more minor operation and a higher anastomosis, becomes acceptable.

The operation then becomes perimesorectal mobilisation, mesorectal transection, anterior resection and primary anastomosis for rectal cancers above around 12 cm. Either 5 cm of mesorectum distal to the tumour or the whole mesorectum must be removed intact with the same preoccupation with clear circumferential margins.

Oncologic Envelopes to Be Excised

There is a need for real understanding of where the satellites of cancer commonly occur since the ideal radical cancer operation should encompass only the common fields of spread that do not exact too high a penalty from the patient. The design of the optimal operation that modern surgery can now offer should take into account the field of spread amenable to surgical removal with the primary tumour, the disabilities inflicted by each component of the surgery and the point in time at which cure becomes impossible by local surgery because metastases have already become established. TME is by far the most important oncologic unit of cure in rectal cancer. A perfect surgery is achieved without inflicting lasting morbidity only if the surgical anatomy of TME is fully understood. Preoperative assessment should supplement full clinical and endoscopic appraisal with a computed tomography (CT) scan of the whole body for metastatic spread, and a specialised magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is necessary for the most precise picture of the primary cancer, its locoregional spread and the anatomical relations of the mesorectum and its contained malignancy.

The Embryologic Basis of Cancer Surgery: Exemplified by Colorectal Cancer: ‘The Holy Plane’ or ‘Holy Space’

Conceptually, TME has a basis in scientific thought which is attractive to all members of the modern multidisciplinary team with background training in basic science. The theory behind it is that all lymphovascular cancer spread will tend, initially at least, to remain within the embryologic hindgut ‘envelope’. The gut of the pre-10 mm embryo extruded itself and secondarily became ‘plastered’ back onto the retroperitoneal structures and into the developing pelvis: it retains its midline lymphovascular integrity, and its artery arises from the front of the aorta. It remains separated from the surrounding paired organs and parietes by a collagenous cobweb of areolar tissue. This allows a degree of movement and is recognisable by the surgeon as a ‘surgical dissection plane’ and is developed by traction and countertraction into an almost entirely avascular space—‘the holy space’. In a number of publications, the authors have drawn attention to the ‘holy plane of rectal surgery’ and attempted to point out the value of painstakingly following this perimesorectal avascular plane around the midline hindgut into the depths of the pelvis as a practical surgical policy. Doing so was eventually shown to improve local recurrence rates in a dramatic way. Straying into the field of cancer spread within the mesorectum was, and still is in conventional practice, an extremely common cause of involved surgical margins and potential residual pelvic disease: straying out can damage the autonomic nerve layers and is a common cause of impotence. Publications from the Karolinska Hospital, Solna, Sweden, demonstrate that more than one-half of all local recurrences are associated with residues of mesorectum left behind by the surgeon. Thus, inadequate TME, i.e. incomplete emptying of the central compartment (within the nerve layer), is a far more important cause of failure than ignoring the internal iliac and other compartments outside the visceral mesorectal ‘core’. This is of great practical importance because, although a challenging dissection, TME is a standard reproducible teaching operation. The lateral compartments are surgically much more difficult and much less rewarding—perhaps best left to a few high-volume specialist surgeons along with other extended procedures such as sacrectomy. In summary, TME anatomy describes the precise ‘emptying’ of the posterial central compartment of the pelvis and the anatomical composition of the relations of each part of the mesorectal surface.

The basic TME hypothesis is essentially that embryology defies the oncologic envelope that encompasses the primary field of all locoregional spread—lymphatic, vascular, perineural and ‘random’. Distally, this tapering hindgut ‘package’, surrounded by the ‘holy plane’, is inserted into the funnel-shaped sloping levator muscles, which merge and overlap with the skeletal external sphincters distally.

The Anatomy of the Mesorectum for the Surgeon: The Planes of the Pelvis

Surgical Anatomy

The original idea of TME was born from the practice of surgery. The mesorectum only becomes a reality for each individual surgeon from enthusiasm for slow, meticulous, painstaking dissection in difficult but achievable planes. These, once recognised and identified, become the defining objectives of the surgery and the redefined building blocks of the anatomy.

The innermost ‘holy plane’ is that which surrounds the midline hindgut within its lymphovascular envelope of visceral fascia—the core—whilst the two surrounding lamellae comprise a neural layer and a Wolffian ridge layer, which develop from the paired structures outside the hindgut. This concept has been made easier to comprehend by the Japanese comparison with the layers of an onion—or perhaps the core of the posterior of two onions separated by Denonvilliers’ septum.

Much of the surgery of the whole gastrointestinal tract is a question of pursuing the planes between embryologically distinct lymphovascular entities. The careful and thoughtful surgeon who is mobilising any part of the large intestine by sharp dissection becomes aware of surgically satisfying planes, which assume special value in his or her journey down into the pelvis. The mesorectum is a complete fatty and lymphovascular surround on all aspects of the middle third of the rectum, which constitutes the greater part of the organ and the most common site for cancer. In the upper third, the anterior aspect is covered only by peritoneum with ‘mesorectum and mesorectosigmoid’ at the back and the sides as the peritoneal reflection tapers forward towards the ‘cul-de-sac’ or recto-vesical pouch. In the lower third of the rectum, little or no fatty tissue intervenes between the anterior aspect of the rectum and the back of the prostate. Posteriorly, the prostate has an important posterior condensed fascial covering called Denonvilliers’ septum. The upper part of the septum is usually adherent to the anterior mesorectal fat of the middle third so that the surgeon must divide this layer from above to enter the plane between the rectum and the prostate in the male. How low this line of division should be may vary according to the position of the cancer—for a very low anterior tumour, it is essential to divide it very low so that the tumour is well cleared anteriorly, preferably with Denonvilliers’ fascia as an extra safety layer. In posterior or higher tumours, the surgeon will give greater priority to avoiding damage to the converging nerves lateral to the edges of Denonvilliers’ septum. In all cases, a u-shaped incision in the septum must be made so as to clear the tumour safely whilst preserving the converging nerves laterally. In the female, the middle third has only a rather thin and tenuous fatty layer between the rectum and vagina with Denonvilliers’ fascia being often scant and difficult to identify; certainly, a recognisable condensed ‘septum’ is often not found as in the male. Is this perhaps because of its dissolution during childbirth or sexual activity? Denonvilliers’ septum is recognised by some embryologists as the downward prolongation of the peritoneum, which has become distally obliterated as a cavity. As we become more fastidious in our dissections, two layers of the septum begin to become apparent. It is now clear to surgeons that, in the male at least, this trapezoidal ‘bib’ with defined lateral margins just medial to the important neurovascular bundles is indeed a reality, and with improving technique, two layers may indeed become apparent (Fig. 4.4).

Fig. 4.4

Denonvilliers’ septum

Posteriorly and posterolaterally, the areolar plane is well defined around the globular expanding bilobed mesorectum. A condensation of the fascia called the rectosacral ligament—or Waldeyer’s fascia—often presents a barrier to the surgeon posteriorly below the promontory. It is essential that this be positively divided with either diathermy or scissors. Beyond it, the forward angulation demands strong anterodistal retraction to facilitate direct visualisation. Understanding the importance of this forward angulation is critical to mastering the traction and countertraction instruments necessary in open, laparoscopic and robotic TME. Confusingly, the middle third of the rectum is often called the horizontal segment because MRIs are typically viewed as if the patient is vertical (Fig. 4.5).

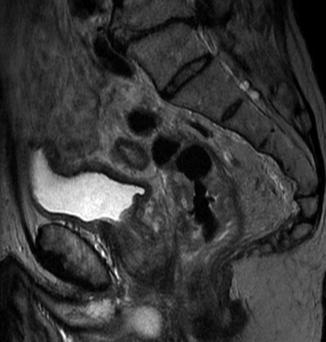

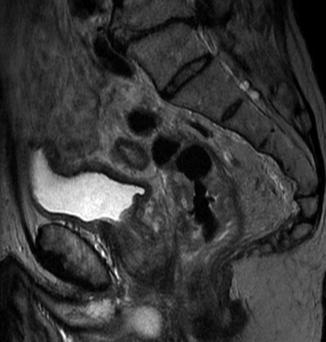

Fig. 4.5

Sagittal MRI cancer at 5 cm posteriorly

The crucial anatomical reality is that this segment is angled posteriorly relative to the anal canal by almost a right angle. The ‘horizontal’ segment follows the curve of the sacrum, and the upper third angles backwards to merge with the sigmoid.

Histopathology Audit

For proper independent audit, the surgeon should not cut the specimen except to open the bowel away from the tumour to let in the formalin. Completeness and intactness of the specimen are crucial factors—ideally it should be one recognisable block of tissue with a fascial covering. Its anatomical orientation and former relations should be identifiable. ‘Specimen-orientated surgery’ has become an established practice, and recognition of the features of the TME specimen and the freedom of its margins from cancer involvement are the key factors of audit. In most cases, naked-eye inspection provides quality control, with microscopic examination of any suspected areas of margin involvement as a logical primary audit objective for the surgeon.

Visual inspection of the front of a well-performed TME specimen should show three clear landmarks:

The cut edge of the peritoneal reflection and the whole ‘cul-de-sac’

The smooth shiny anterior surface of the anterior mesorectum of the middle third—Denonvilliers’ fascia—or the rectogenital septum (upper half)

The anterior aspect of the anorectal muscle—in the lowest anterior resections or abdominoperineal excision (APE) specimens only

Laterally, the fatty mesorectum expands distally beyond an anteroposterior groove made by the nervi erigentes so that an embryologically perfect specimen has a lateral dilatation distally—corresponding with the part related to the inside of the levator muscles beyond their origins from the pelvic sidewall. Posteriorly, a perfect specimen exhibits perfectly curved ‘buttocks’ with a central midline groove corresponding to the anococcygeal raphe (the pubococcygeus muscle) with distal dilatations from beyond the nerve pillars (Fig. 4.6).

Fig. 4.6

Posterior aspect of a TME, ‘the buttocks’

Modern Imaging: Fine-Slice High-Resolution MRI

Brown, Blomqvist and others have shown us that specialised fine-slice high-resolution MRI can visualise this ‘holy plane’ before the surgery and thus predict the detail of the oncologic specimen that the surgeon endeavours to remove and its relationship to the tentacles of tumour. The recent ‘MERCURY’ study from the Pelican Centre in Basingstoke has demonstrated reliable equivalence between MRI prediction and histopathologic reality. It also demonstrates that a 1-mm mesorectal ‘clearance’ does indeed predict a ‘safe margin’ provided the surgeon is faithfully following the ‘holy plane’. Surprisingly, it is not a component of any staging system; extra-mural vascular invasion was an even more important prognostic indicator than nodal involvement at the N1 level. Some may take this as an indication for giving preoperative CRT to all patients with EMVI.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree