Primary urethral cancers represent less than 1% of genitourinary malignancy. Given this is an uncommon disease, there are limited data to guide diagnostic and treatment strategies. Surgical extirpation remains the standard for most patients, with the addition of chemotherapy and radiation therapy in select patients. The surgical approach to urethral cancer depends largely on the location and extent of the tumor.

Primary urethral cancers represent less than 1% of genitourinary malignancy. Given this is an uncommon disease, there are limited data to guide diagnostic and treatment strategies. Surgical extirpation remains the standard for most patients, with the addition of chemotherapy and radiation therapy in select patients. The surgical approach to urethral cancer depends largely on the location and extent of the tumor.

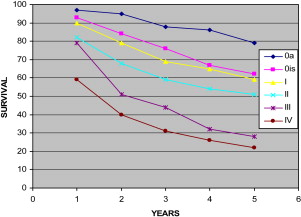

Survival

Survival in men and women depends on the stage ( Fig. 1 ). See Appendix for TNM staging.

Male urethral cancer

The diagnosis of urethral cancer can be elusive. Although most urethral cancers are associated with symptoms (ie, bleeding, lower urinary tract symptoms), concomitant disease may delay diagnosis. In men, urethral cancer is commonly associated with stricture disease, sexually transmitted disease, immunosuppression, or previous urethral surgery or radiation therapy. The mean age at presentation is approximately 60 years.

Anatomic Considerations

The typical epithelial neoplasms in the male urethra are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma, and urothelial carcinoma (UC). Overall, SCC represents the most common histology. Other variant malignancies, such as villous adenocarcinoma are rare ( Fig. 2 ).

Historically, primary cancers of the urethra have been divided into 2 regions: anterior and posterior. Anterior is more common than posterior. Some investigators have described distal urethral cancers to differentiate those from within the bulb or other more proximal locations. In general, distal cancers or penile urethral cancers are diagnosed at an earlier stage and are potentially more amenable to local treatment (organ-preserving). Correspondingly, survival has been more favorable for patients with anterior tumors compared with posterior tumors. A possible explanation for lower stage at diagnosis is that anterior tumors may be more obstructive because of a smaller caliber distal urethral or, associated with signs (ie, a palpable mass). The surgical approach to urethral cancers is dependent on stage and location with less importance on grade and histopathologic type.

Historical Perspective

Thiaudierre is credited with the first description of a male urethral cancer case in 1834. In 1951, McCrea and Furlong reviewed more than 200 patients. The investigators noted that no patient lived more than 10 months from the time of diagnosis without definitive treatment. A follow-up article in the same era reported 5 cases requiring penile amputation and 2 that required radical cystectomy for male urethra carcinoma. These investigators commented that when they reviewed the literature they were “unable to arrive at any decision regarding the value of any specific type of treatment.” Unfortunately, since that time, there have been few data to allow consensus on how to best manage primary male urethral cancer.

In the 1960s, Kaplan and colleagues reported a median survival of only 3 months and the longest survival of 15 months in 46 men who had only palliation or no treatment at all. This report did conclude that radical surgery could be effective and that in most cases adequate local control of the disease would translate into improved survival. In another series of posteriorly located tumors, 5-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) was 30% following radical surgery and 3% without treatment.

In the early 1980s, urologists from MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) detailed the types of exenterative surgery they believed necessary to provide local control of these cancers. The report from MSKCC had more than 50% CSS when neoadjuvant radiation was added to radical excision including inferior pubectomy. Around the same time, Bracken reported on 3 posterior urethral cancers and described a 2-stage procedure that involved an ileal conduit and then an anterior exenteration and total emasculation with en bloc pubectomy. In this report, the men were free of disease at 18 to 60 months follow-up and it was concluded that, “no less radical treatment seems appropriate.” Although not debating the paramount importance of local control, to equate a local recurrence with lethality based on these historic reports does not justify such exenterative surgery in all cases of urethral cancer in the modern era.

Contemporary Series

A MDACC series describes the presentation and treatment of 23 men with urethral cancer between 1979 and 1990 and was a follow-up from their previous report. The overall survival (OS) for this group was 52% at a mean follow-up of 50 months (range 5–156 months). Approximately two-thirds of the patients had tumors in the distal anterior urethra and one-third within the bulb region. The investigators observed that survival was dependent on stage, grade, and location; for instance, patients with fossa navicularis lesions and all grade I tumors were associated with 100% survival at last follow-up. Patients with penile urethral tumors had 60% CSS at a mean follow-up of 48 months and patients with bulbomembranous urethral tumors had 29% CSS at a mean follow-up of 31 months. This report also demonstrated that radiation therapy alone did not provide local disease control and that chemotherapy may be beneficial for patients who present with metastatic disease. Based on the investigators’ experience, they concluded that tumors in the fossa navicularis and penile urethra should be treated with distal urethrectomy and partial penectomy; and tumors in the bulbomembranous urethra should be treated with en bloc resection of the penis, scrotum, prostate, bladder and inferior pubic rami. This was a similar conclusion that had been made in the previous issue of Urologic Clinics of North America on this topic in 1992.

MSKCC has provided the largest and longest single institution series to date of 46 men with primary urethral cancers from 1958 to 1996. Median follow-up was 125 months. Very similar to the MDACC survival data, MSKCC reported 5-year CSS was approximately 50% and the OS was 42%. Location of the lesion was associated with outcome as 26% survival was observed for patients with bulbar tumors compared with 69% for patients with distal anterior urethral tumors. Not surprisingly tumor stage was also associated with outcome as patients with noninvasive lesions (<T1) had 83% OS compared with 36% for invasive lesions (≥T1). Disease-free survival was 38% for patients with distal tumors compared with 14% for patients with tumors in the bulb. As with most series, treatment was not standardized in all patients. A somewhat alarming finding within their study was that survival rates appeared unchanged when they compared 1975 and before with 1976 and after. Any meaningful conclusions are hard to draw from this observation given the relatively small numbers and lack of balance of stage/grade/location distributions within these time periods. Furthermore, these large series from MDACC and MSKCC and others perhaps do not reflect how all men with urethral cancers present, are treated, and their outcomes. There is an inherent bias in these types of reporting as cases sent to tertiary care cancer centers are probably different and more advanced than the cases that are handled within the community. Nonetheless, like the MDACC series, most of the MSKCC series was composed of symptomatic SCCs. There was an obvious difference with the MSKCC series in that two-thirds of cases were located within the bulb and only one-third within the distal anterior urethra, which was the opposite in the MDACC series. Of the 46 cases at MSKCC, 40 underwent surgery alone and 6 had preoperative radiation. It is not clear whether these 6 men had planned resection after radiation or whether they required a salvage surgery. The men who did receive radiation were typically of higher stage (n = 3 for T3 and n = 3 for T4) and did not seem to fare as well. In additionally, Zeidman and colleagues summarized the ineffective results of radiation alone on male urethral cancers. A second primary malignancy was discovered in 9 men during the follow-up, which might be explained by concurrent (n = 10) or previous smoking history (n = 31). Within this report, it is difficult to detail how many if any received postoperative chemotherapy but it seems none received it preoperatively despite concluding that the locally advanced cases should be treated aggressively with preoperative chemotherapy and radiation. When present (n = 14), the distant metastatic site most commonly involved was the lung. This report concluded that newer treatment strategies are needed and the investigators proposed that locally advanced cases should be managed with neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by penectomy for distal anterior urethral lesions and with the addition of an anterior exenteration for more proximal (posterior) lesions.

Another series by Gheiler and colleagues from 1980 to 1996 described the Wayne State experience for 11 men with a mean follow-up of 40 months. Distal lesions and lower-stage lesions fared better than proximal and higher-stage lesions. In particular, with this study, 4 men (T3–4, N0–2) underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by surgical resection and 2 of the 4 were disease-free at follow-up. The investigators acknowledged that the numbers were small but their findings suggested that the addition of this neoadjuvant regimen might result in better survival. They also suggested that Ta-T2N0 cases could be managed surgically perhaps without multimodal therapy but their series on which this statement was based also included about half women.

Another combined (male/female) series from 1958 to 1998 that included 8 men showed that those with higher-stage lesions (T2M1, T3, and T4) were dead of their disease at 10, 56, and 4 months, respectively. With the lower-stage lesions (T1–2) no metastasis developed; 2 underwent transurethral resection alone (TUR) and 1 a wide local excision. Although not the first series to report on organ/penile preservation, perhaps there are cases that definitely do not require a more radical excision. It is not clear that this is true only for the lower-stage lesions but potentially with the inclusion of other modalities, penile preservation can be accomplished. A European study from Mainz, Germany, described the management of male urethral cancers (n = 9) between 1986 and 2006. As expected various treatments (only 2 requiring penectomy) were provided for the anteriorly located cancers (n = 6) and the 3 that involved the prostatic urethra (minimal details provided) involved a TUR alone. With a median follow-up of 20 months all but 1 were disease free. Although the follow-up is short most would believe that survival rates are improving in the current era and 4 of the 6 men had penile-preserving surgery. Most would agree that penile-preserving surgery can be accomplished for the properly selected urethral cancer case.

Penile-preserving Surgery

In the previous Urologic Clinics of North America , Zeidman and colleagues presented 7 series of conservatively managed male urethral cancers. Of the 19 men, cases were handled by either local excision, fulguration, or TUR (surgical details without precision). Seven were SCCs and 7 were transitional cell cancers (TCCs). Eleven were in the distal urethra and 6 were in the bulb and all were free of disease at follow-up. Within this series, Mandler and Pool had 3 men whom were managed with local excision in the distal urethra (1 SCC, 2 TCC, grade and T stage not provided) and follow-up was not short at 2, 10, and 20 years. In 3 of the more modern series provided, conservatively managed patients (ie, penile-preserving) were performed at MSKCC (n = 13), MDACC (n = 2), and Wayne State (n = 4), and all had disease-free status at follow-up. Nonetheless, these are probably highly selected cases and this is not an endorsement for penile-preserving surgery for all cases of urethral cancer. A low-grade and low-stage distal urethral cancer might be properly suited for distal urethrectomy and partial or radical penectomy in terms of local control but could definitely constitute over treatment and the sequelae of penile loss. On the other hand, in the properly evaluated and motivated patient with urethral cancer, penile-preserving surgery could be doable without compromising cancer control. Most of these cases outlined earlier have involved lower-stage and probably lower-grade lesions; however, further discussion focuses more on advanced stages as well as a series of penile-preserving cases.

Baskin and Turzan first reported on a case involving neoadjuvant chemoradiation for SCC of the anterior urethra in 1992. The patient then underwent a distal urethrectomy and had a pT0 response. The rationale and regimen of neoadjuvant chemoradiation for SCC of the penis or urethra, which has paralleled other anatomic sites such as the anus, is outlined elsewhere in this issue.

Bird and Coburn described 3 men with invasive SCC urethral cancers (T3, corporal cavernosa invasion) located within the bulb and/or penile urethra who did not want emasculation. Neither neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy was provided. Within this case report, the surgical approach is described for phallus preservation along with the glans penis with a subcutaneous penectomy/urethrectomy. No local recurrences were seen but distant progression was present during follow-up. These lesions were also away from the glans and not fixed to the skin. On this later note outlined by these investigators, such a surgery could still be accomplished even if a wide ellipse of skin is taken. This article also clearly showed that the glans penis can survive via the vascular tributaries within the penile skin. Given that such a phallus is nonfunctional, it is not known if patients would be better served with this approach or have a penectomy and go onto phallic reconstruction as detailed elsewhere in the issue.

Davis and colleagues report on their series of conservatively managed penile and urethral carcinomas. There was only 1 case of male urethral cancer (SCC) who underwent a urethrectomy alone for a T2 lesion within the bulb. The patient eventually succumbed to the disease without local recurrence 2 years later as a result of progression that started with pelvic lymphadenopathy. This case also highlights the need to potentially manage lymph node drainage prophylactically as a node dissection was not performed or detailed in this report.

Kent and colleagues presented successful management of a case of urethral TCC with squamous differentiation in the distal urethra diagnosed as a T1 by initial TUR and was also N+. MVAC chemotherapy was provided as well as salvage chemotherapy and the patient was rendered pT0 and was free of recurrence locally and systemically at 39 months. This case and those outlined earlier highlight that metastasis still drives survival and that management of the primary should take this into account and not subject the patient to surgery on the primary lesion that may have little effect on the CSS.

These cases involved the distal anterior urethra. The next case involves an invasive SCC of the bulb. Penile preservation was accomplished and surgery was a complete urethrectomy along with a nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. The bladder was left in situ and bladder neck closure was performed with a Mitrofanoff reconstruction. Surgical pathology revealed a T4 secondary to involvement of testicular tunica and surgery also required an orchiectomy. Adjuvant pelvic chemoradiation was provided and at 15 months the patient was disease-free. This case shows that the native bladder can often be used as it is frequently unaffected by bulb lesions or primary male urethral cancers in general. It also highlights the resourcefulness of the surgeons. Cadaveric tensor fascia lata was used to reconstruct the tunica of the ventral corpora cavernosal bodies in their attempt to preserve erectile functioning and efforts to maintain adequate surgical margins. The surgical approaches are obviously evolving from earlier recommendations of emasculation and anterior exenteration along with inferior pubectomy and other attempts at organ preservation.

The largest series to date, and the most contemporary, on penile-preserving surgery for distal urethral cancers without preoperative treatment comes from the United Kingdom. The presentation and outcome of 18 men treated consecutively is outlined for a 5-year time period. The median follow-up was only 21 months. A surgical treatment and reconstruction algorithm was created and presented within this report based on the exact location of the lesions. There have been no local recurrences to date, 6 of the men did have nodal disease, and there have been 2 cancer-related deaths. Obviously such a series will need to withstand the test of time over a longer follow-up but it underscores the point that most of the time any systemic component of cancer will drive survival. An additional highlight of this report is the issue of what constitutes appropriate surgical margins in urethral cancer. Former dogmatic teaching in the surgical management of penile cancer was a 2 cm margin but this was not based on high-level evidence and more recent studies have questioned the necessity of such a margin. In this study by Smith and colleagues, 8 men had margins less than 5 mm but it is hard to know exactly where the margin was taken. When it comes to urethral cancer, there is really a vacuum of recommendations. Penile cancer margins are primarily based on the skin; however, this does not readily apply to urethral cancer. Margins in urethral cancer encompass the proximal and distal urethral segments as well as the dorsally located corpora cavernosa bodies and ventrally the penile skin. This article also highlighted the usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for surgically planning in penile cancer or with management in general, and its potential applicability in urethral cancer.

Although not a pure surgical series, Cohen and colleagues have presented their series from the Lahey Clinic of 18 men with invasive urethral cancer treated between 1991 and 2006 with the same concurrent chemoradiation protocol. Half of the tumors were located in the penile urethra and the other half in the bulbomembranous urethra. Ninety-five percent of the cases were SCC. A complete response (CR) was seen in 15/18 or 83% and the reported 5-year OS was 60% and a CSS of 83%. In the 3 nonresponders to the chemoradiation, salvage surgery (details not provided) was performed but all died of their disease. There was a reported local recurrence rate of 30% or 5/15 who had an initial CR and 4 of these underwent salvage surgery. Thus, 10 of 18 men had a durable CR and of these 10, 3 required a complex urethral reconstruction. All the men essentially required posttreatment management of treatment-related stricture disease with most having cystoscopic intervention (except for the cases requiring salvage surgery and the 3 having a complex urethral reconstruction). This center kept the same treatment algorithm for this rare malignancy during this time period and provides these unique data. There is no doubt that surgery alone cannot be curative in some locally advanced lesions of the urethra. Unfortunately, the timing and/or the exact role of the other treatment modalities is not precisely known. Furthermore, the nature of the biopsies are not described in this study; for instance, did they debulk the lesions endoscopically or perform an open local excision or just take the biopsy before the chemoradiation?

When a surgeon is considering a penile-preserving operation for cancer of the urethra, the first step is assessing the primary lesion and whether it is amenable to such an operation. An examination along with cystoscopy and retrograde urethrography is essential and at times an MRI scan can be useful. Fig. 3 illustrates the potential use of MRI. A biopsy should be performed to determine the histologic subtype especially if neoadjuvant chemotherapy is considered. The biopsy, usually done endoscopically, can also help determine the grade and potential stage/local depth.

During consideration of a penile-preserving operation, there is a balance between oncologic principles (local control), functionality (ability to void standing and erectile function), and the patient’s desires along with his comorbidity and the rest of his metastatic work-up. In cases that cannot be managed with penile preservation, consideration should be given to a preoperative plastic surgery consultation along with evaluation by psychiatry for body image changes. Furthermore, for those cases managed conservatively, the exact nature of the surveillance timing or methods are not known. The obvious choices are cystoscopy and cytology along with examination and potentially the incorporation of imaging. Figs. 4 and 5 are examples of penile preservation.

Lymph Node Management

The role of lymph node dissection in the management of urethral cancers is even less clear than how to manage the primary. The management of lymphatic drainage and controversies in ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy as well as imaging of the groins are highlighted in different articles in this issue. Prophylactic groin dissection for urethral cancers was felt to be controversial dating back to the 1960s. On the other hand, MDACC reports demonstrated that cures are possible with limited lymph node disease. The biology of urethral SCC can mirror that of penile SCC; thus, lymph node dissection should be considered for limited nodal disease or neoadjuvant chemotherapy incorporated for cN2 disease or higher. A prophylactic node dissection could be planned for high-grade T1 lesions or higher. Lesions involving the fossa and penile urethra typically involve the groin nodes primarily; however, lesions in the bulb and posterior urethra can also involve the pelvic lymph nodes so surgery should take this into account.

Primary Prostatic Urethral Cancer

Primary cancers involving the prostatic urethra are even more rare than those involving the anterior urethra. In the previous issue of Urologic Clinics of North America , Zeidman and colleagues presented survival data on 16 prostatic urethral cancers with an estimated 5-year survival rate of 25%. Further details are not known. Cheville and colleagues presented Mayo Clinic data on 50 prostate UCs or TCCs but approximately two-thirds had a history of bladder cancer. Noninvasive prostatic urethral disease along with disease involving only the ducts or acini had a 5-year CSS of 100%. On the other hand, prostate TCC stromal involvement had a 5-year CSS of 45%. Palou and colleagues recently reviewed urothelial carcinomas of the prostate as part of a consensus conference. Primary cancers are rare without a history of or concomitant bladder cancer. This type of cancer can be frequently understaged and usually requires an extensive TUR along with bladder interrogation to determine its exact involvement and consideration of a transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate. Primary noninvasive prostatic urethral cancer could be managed in the same way as noninvasive bladder cancer. On the other hand, there are no data supporting any optimal treatment or support for a radical prostatectomy or radical cystoprostatectomy for the rare, invasive, organ-confined, primary cancer of the prostatic urethra. The surgical approach needs to be geared to the stage of the cancer (see Appendix for TNM stage).

Summary

Surgery plays an instrumental role in the management of male urethral cancers. At times it might be enough for a cure and at other times it might not. Exactly which cases benefit from chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy is unresolved. Even in cases that are managed exclusively with chemoradiation, the urologist plays a role in establishing the diagnosis but is also involved in the morbidity of the treatment on the urethra. Overall, the urologist should involve colleagues within medical and radiation oncology when it comes to invasive lesions. Given the rarity of these lesions, clinical trials or guidelines have not been established. The outcomes seem most dependent on the stage and grade at presentation as well as the location along the male urethra. The first step in the process should be assessment of the primary in terms of stage and extent as well as a metastatic work-up. There is no doubt that over time radiographic imaging and reconstructive surgery efforts have improved. With proper selection, penile-preserving surgery should be considered in the management of male urethral cancers. In addition, surgical management of lymph node drainage should be considered for those cases involving invasive lesions and should parallel those of penile SCC.

Male urethral cancer

The diagnosis of urethral cancer can be elusive. Although most urethral cancers are associated with symptoms (ie, bleeding, lower urinary tract symptoms), concomitant disease may delay diagnosis. In men, urethral cancer is commonly associated with stricture disease, sexually transmitted disease, immunosuppression, or previous urethral surgery or radiation therapy. The mean age at presentation is approximately 60 years.

Anatomic Considerations

The typical epithelial neoplasms in the male urethra are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma, and urothelial carcinoma (UC). Overall, SCC represents the most common histology. Other variant malignancies, such as villous adenocarcinoma are rare ( Fig. 2 ).

Historically, primary cancers of the urethra have been divided into 2 regions: anterior and posterior. Anterior is more common than posterior. Some investigators have described distal urethral cancers to differentiate those from within the bulb or other more proximal locations. In general, distal cancers or penile urethral cancers are diagnosed at an earlier stage and are potentially more amenable to local treatment (organ-preserving). Correspondingly, survival has been more favorable for patients with anterior tumors compared with posterior tumors. A possible explanation for lower stage at diagnosis is that anterior tumors may be more obstructive because of a smaller caliber distal urethral or, associated with signs (ie, a palpable mass). The surgical approach to urethral cancers is dependent on stage and location with less importance on grade and histopathologic type.

Historical Perspective

Thiaudierre is credited with the first description of a male urethral cancer case in 1834. In 1951, McCrea and Furlong reviewed more than 200 patients. The investigators noted that no patient lived more than 10 months from the time of diagnosis without definitive treatment. A follow-up article in the same era reported 5 cases requiring penile amputation and 2 that required radical cystectomy for male urethra carcinoma. These investigators commented that when they reviewed the literature they were “unable to arrive at any decision regarding the value of any specific type of treatment.” Unfortunately, since that time, there have been few data to allow consensus on how to best manage primary male urethral cancer.

In the 1960s, Kaplan and colleagues reported a median survival of only 3 months and the longest survival of 15 months in 46 men who had only palliation or no treatment at all. This report did conclude that radical surgery could be effective and that in most cases adequate local control of the disease would translate into improved survival. In another series of posteriorly located tumors, 5-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) was 30% following radical surgery and 3% without treatment.

In the early 1980s, urologists from MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) detailed the types of exenterative surgery they believed necessary to provide local control of these cancers. The report from MSKCC had more than 50% CSS when neoadjuvant radiation was added to radical excision including inferior pubectomy. Around the same time, Bracken reported on 3 posterior urethral cancers and described a 2-stage procedure that involved an ileal conduit and then an anterior exenteration and total emasculation with en bloc pubectomy. In this report, the men were free of disease at 18 to 60 months follow-up and it was concluded that, “no less radical treatment seems appropriate.” Although not debating the paramount importance of local control, to equate a local recurrence with lethality based on these historic reports does not justify such exenterative surgery in all cases of urethral cancer in the modern era.

Contemporary Series

A MDACC series describes the presentation and treatment of 23 men with urethral cancer between 1979 and 1990 and was a follow-up from their previous report. The overall survival (OS) for this group was 52% at a mean follow-up of 50 months (range 5–156 months). Approximately two-thirds of the patients had tumors in the distal anterior urethra and one-third within the bulb region. The investigators observed that survival was dependent on stage, grade, and location; for instance, patients with fossa navicularis lesions and all grade I tumors were associated with 100% survival at last follow-up. Patients with penile urethral tumors had 60% CSS at a mean follow-up of 48 months and patients with bulbomembranous urethral tumors had 29% CSS at a mean follow-up of 31 months. This report also demonstrated that radiation therapy alone did not provide local disease control and that chemotherapy may be beneficial for patients who present with metastatic disease. Based on the investigators’ experience, they concluded that tumors in the fossa navicularis and penile urethra should be treated with distal urethrectomy and partial penectomy; and tumors in the bulbomembranous urethra should be treated with en bloc resection of the penis, scrotum, prostate, bladder and inferior pubic rami. This was a similar conclusion that had been made in the previous issue of Urologic Clinics of North America on this topic in 1992.

MSKCC has provided the largest and longest single institution series to date of 46 men with primary urethral cancers from 1958 to 1996. Median follow-up was 125 months. Very similar to the MDACC survival data, MSKCC reported 5-year CSS was approximately 50% and the OS was 42%. Location of the lesion was associated with outcome as 26% survival was observed for patients with bulbar tumors compared with 69% for patients with distal anterior urethral tumors. Not surprisingly tumor stage was also associated with outcome as patients with noninvasive lesions (<T1) had 83% OS compared with 36% for invasive lesions (≥T1). Disease-free survival was 38% for patients with distal tumors compared with 14% for patients with tumors in the bulb. As with most series, treatment was not standardized in all patients. A somewhat alarming finding within their study was that survival rates appeared unchanged when they compared 1975 and before with 1976 and after. Any meaningful conclusions are hard to draw from this observation given the relatively small numbers and lack of balance of stage/grade/location distributions within these time periods. Furthermore, these large series from MDACC and MSKCC and others perhaps do not reflect how all men with urethral cancers present, are treated, and their outcomes. There is an inherent bias in these types of reporting as cases sent to tertiary care cancer centers are probably different and more advanced than the cases that are handled within the community. Nonetheless, like the MDACC series, most of the MSKCC series was composed of symptomatic SCCs. There was an obvious difference with the MSKCC series in that two-thirds of cases were located within the bulb and only one-third within the distal anterior urethra, which was the opposite in the MDACC series. Of the 46 cases at MSKCC, 40 underwent surgery alone and 6 had preoperative radiation. It is not clear whether these 6 men had planned resection after radiation or whether they required a salvage surgery. The men who did receive radiation were typically of higher stage (n = 3 for T3 and n = 3 for T4) and did not seem to fare as well. In additionally, Zeidman and colleagues summarized the ineffective results of radiation alone on male urethral cancers. A second primary malignancy was discovered in 9 men during the follow-up, which might be explained by concurrent (n = 10) or previous smoking history (n = 31). Within this report, it is difficult to detail how many if any received postoperative chemotherapy but it seems none received it preoperatively despite concluding that the locally advanced cases should be treated aggressively with preoperative chemotherapy and radiation. When present (n = 14), the distant metastatic site most commonly involved was the lung. This report concluded that newer treatment strategies are needed and the investigators proposed that locally advanced cases should be managed with neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by penectomy for distal anterior urethral lesions and with the addition of an anterior exenteration for more proximal (posterior) lesions.

Another series by Gheiler and colleagues from 1980 to 1996 described the Wayne State experience for 11 men with a mean follow-up of 40 months. Distal lesions and lower-stage lesions fared better than proximal and higher-stage lesions. In particular, with this study, 4 men (T3–4, N0–2) underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by surgical resection and 2 of the 4 were disease-free at follow-up. The investigators acknowledged that the numbers were small but their findings suggested that the addition of this neoadjuvant regimen might result in better survival. They also suggested that Ta-T2N0 cases could be managed surgically perhaps without multimodal therapy but their series on which this statement was based also included about half women.

Another combined (male/female) series from 1958 to 1998 that included 8 men showed that those with higher-stage lesions (T2M1, T3, and T4) were dead of their disease at 10, 56, and 4 months, respectively. With the lower-stage lesions (T1–2) no metastasis developed; 2 underwent transurethral resection alone (TUR) and 1 a wide local excision. Although not the first series to report on organ/penile preservation, perhaps there are cases that definitely do not require a more radical excision. It is not clear that this is true only for the lower-stage lesions but potentially with the inclusion of other modalities, penile preservation can be accomplished. A European study from Mainz, Germany, described the management of male urethral cancers (n = 9) between 1986 and 2006. As expected various treatments (only 2 requiring penectomy) were provided for the anteriorly located cancers (n = 6) and the 3 that involved the prostatic urethra (minimal details provided) involved a TUR alone. With a median follow-up of 20 months all but 1 were disease free. Although the follow-up is short most would believe that survival rates are improving in the current era and 4 of the 6 men had penile-preserving surgery. Most would agree that penile-preserving surgery can be accomplished for the properly selected urethral cancer case.

Penile-preserving Surgery

In the previous Urologic Clinics of North America , Zeidman and colleagues presented 7 series of conservatively managed male urethral cancers. Of the 19 men, cases were handled by either local excision, fulguration, or TUR (surgical details without precision). Seven were SCCs and 7 were transitional cell cancers (TCCs). Eleven were in the distal urethra and 6 were in the bulb and all were free of disease at follow-up. Within this series, Mandler and Pool had 3 men whom were managed with local excision in the distal urethra (1 SCC, 2 TCC, grade and T stage not provided) and follow-up was not short at 2, 10, and 20 years. In 3 of the more modern series provided, conservatively managed patients (ie, penile-preserving) were performed at MSKCC (n = 13), MDACC (n = 2), and Wayne State (n = 4), and all had disease-free status at follow-up. Nonetheless, these are probably highly selected cases and this is not an endorsement for penile-preserving surgery for all cases of urethral cancer. A low-grade and low-stage distal urethral cancer might be properly suited for distal urethrectomy and partial or radical penectomy in terms of local control but could definitely constitute over treatment and the sequelae of penile loss. On the other hand, in the properly evaluated and motivated patient with urethral cancer, penile-preserving surgery could be doable without compromising cancer control. Most of these cases outlined earlier have involved lower-stage and probably lower-grade lesions; however, further discussion focuses more on advanced stages as well as a series of penile-preserving cases.

Baskin and Turzan first reported on a case involving neoadjuvant chemoradiation for SCC of the anterior urethra in 1992. The patient then underwent a distal urethrectomy and had a pT0 response. The rationale and regimen of neoadjuvant chemoradiation for SCC of the penis or urethra, which has paralleled other anatomic sites such as the anus, is outlined elsewhere in this issue.

Bird and Coburn described 3 men with invasive SCC urethral cancers (T3, corporal cavernosa invasion) located within the bulb and/or penile urethra who did not want emasculation. Neither neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy was provided. Within this case report, the surgical approach is described for phallus preservation along with the glans penis with a subcutaneous penectomy/urethrectomy. No local recurrences were seen but distant progression was present during follow-up. These lesions were also away from the glans and not fixed to the skin. On this later note outlined by these investigators, such a surgery could still be accomplished even if a wide ellipse of skin is taken. This article also clearly showed that the glans penis can survive via the vascular tributaries within the penile skin. Given that such a phallus is nonfunctional, it is not known if patients would be better served with this approach or have a penectomy and go onto phallic reconstruction as detailed elsewhere in the issue.

Davis and colleagues report on their series of conservatively managed penile and urethral carcinomas. There was only 1 case of male urethral cancer (SCC) who underwent a urethrectomy alone for a T2 lesion within the bulb. The patient eventually succumbed to the disease without local recurrence 2 years later as a result of progression that started with pelvic lymphadenopathy. This case also highlights the need to potentially manage lymph node drainage prophylactically as a node dissection was not performed or detailed in this report.

Kent and colleagues presented successful management of a case of urethral TCC with squamous differentiation in the distal urethra diagnosed as a T1 by initial TUR and was also N+. MVAC chemotherapy was provided as well as salvage chemotherapy and the patient was rendered pT0 and was free of recurrence locally and systemically at 39 months. This case and those outlined earlier highlight that metastasis still drives survival and that management of the primary should take this into account and not subject the patient to surgery on the primary lesion that may have little effect on the CSS.

These cases involved the distal anterior urethra. The next case involves an invasive SCC of the bulb. Penile preservation was accomplished and surgery was a complete urethrectomy along with a nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. The bladder was left in situ and bladder neck closure was performed with a Mitrofanoff reconstruction. Surgical pathology revealed a T4 secondary to involvement of testicular tunica and surgery also required an orchiectomy. Adjuvant pelvic chemoradiation was provided and at 15 months the patient was disease-free. This case shows that the native bladder can often be used as it is frequently unaffected by bulb lesions or primary male urethral cancers in general. It also highlights the resourcefulness of the surgeons. Cadaveric tensor fascia lata was used to reconstruct the tunica of the ventral corpora cavernosal bodies in their attempt to preserve erectile functioning and efforts to maintain adequate surgical margins. The surgical approaches are obviously evolving from earlier recommendations of emasculation and anterior exenteration along with inferior pubectomy and other attempts at organ preservation.

The largest series to date, and the most contemporary, on penile-preserving surgery for distal urethral cancers without preoperative treatment comes from the United Kingdom. The presentation and outcome of 18 men treated consecutively is outlined for a 5-year time period. The median follow-up was only 21 months. A surgical treatment and reconstruction algorithm was created and presented within this report based on the exact location of the lesions. There have been no local recurrences to date, 6 of the men did have nodal disease, and there have been 2 cancer-related deaths. Obviously such a series will need to withstand the test of time over a longer follow-up but it underscores the point that most of the time any systemic component of cancer will drive survival. An additional highlight of this report is the issue of what constitutes appropriate surgical margins in urethral cancer. Former dogmatic teaching in the surgical management of penile cancer was a 2 cm margin but this was not based on high-level evidence and more recent studies have questioned the necessity of such a margin. In this study by Smith and colleagues, 8 men had margins less than 5 mm but it is hard to know exactly where the margin was taken. When it comes to urethral cancer, there is really a vacuum of recommendations. Penile cancer margins are primarily based on the skin; however, this does not readily apply to urethral cancer. Margins in urethral cancer encompass the proximal and distal urethral segments as well as the dorsally located corpora cavernosa bodies and ventrally the penile skin. This article also highlighted the usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for surgically planning in penile cancer or with management in general, and its potential applicability in urethral cancer.

Although not a pure surgical series, Cohen and colleagues have presented their series from the Lahey Clinic of 18 men with invasive urethral cancer treated between 1991 and 2006 with the same concurrent chemoradiation protocol. Half of the tumors were located in the penile urethra and the other half in the bulbomembranous urethra. Ninety-five percent of the cases were SCC. A complete response (CR) was seen in 15/18 or 83% and the reported 5-year OS was 60% and a CSS of 83%. In the 3 nonresponders to the chemoradiation, salvage surgery (details not provided) was performed but all died of their disease. There was a reported local recurrence rate of 30% or 5/15 who had an initial CR and 4 of these underwent salvage surgery. Thus, 10 of 18 men had a durable CR and of these 10, 3 required a complex urethral reconstruction. All the men essentially required posttreatment management of treatment-related stricture disease with most having cystoscopic intervention (except for the cases requiring salvage surgery and the 3 having a complex urethral reconstruction). This center kept the same treatment algorithm for this rare malignancy during this time period and provides these unique data. There is no doubt that surgery alone cannot be curative in some locally advanced lesions of the urethra. Unfortunately, the timing and/or the exact role of the other treatment modalities is not precisely known. Furthermore, the nature of the biopsies are not described in this study; for instance, did they debulk the lesions endoscopically or perform an open local excision or just take the biopsy before the chemoradiation?

When a surgeon is considering a penile-preserving operation for cancer of the urethra, the first step is assessing the primary lesion and whether it is amenable to such an operation. An examination along with cystoscopy and retrograde urethrography is essential and at times an MRI scan can be useful. Fig. 3 illustrates the potential use of MRI. A biopsy should be performed to determine the histologic subtype especially if neoadjuvant chemotherapy is considered. The biopsy, usually done endoscopically, can also help determine the grade and potential stage/local depth.