Fig. 24.1

Secretin-stimulated MRI. a Normal result showing normal diameter duct with free flow into jejunum ( arrows) indicating no obstruction at the pancreatico-jejunostomy anastomotic ( PJA). (With permission from [3] © Elsevier). b Abnormal result with distended duct and no flow into jejunum indicating obstruction at the PJA. (With permission from [4] © Elsevier)

Strictures may also be classified potentially by their functional effect on pancreatic exocrine function. While there are many tests that have been used to accomplish this, fecal elastase-1 concentration seems to be most useful in doing so [4, 5].

Exocrine Function of the Pancreas After Pancreato-Jejunostomy or Pancreato-Gastrostomy

Many patients who have PD develop pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and require pancreatic enzyme replacement. The principal putative causes are obstruction of at the pancreatic anastomosis to the jejunum or stomach, the resection of functional pancreatic parenchyma, and underlying diseases of the exocrine pancreas such as chronic pancreatitis or atrophy secondary to malignant obstruction. Until recently, there has been little work in sorting out these causes. As noted above, the use of dynamic MRP to evaluate patency of pancreatic anastomoses to jejunum or stomach and fecal elastase-1 concentration to measure exocrine function have furthered our understanding.

Sho et al. studied 34 post-PD patients who had pancreatojejunostomy with secretin MRP [3]. Secretion into the jejunal loop after secretin stimulation was graded as poor, moderate, or good (Grades 1–3 respectively) by two radiologists. Distention of the jejunal loop in the good secretors was obvious. Patency of the anastomosis could also be seen directly. About one-third of patients were in each group. Symptoms such as diarrhea and pain were present only in 1 of 11 patients in the “good” group, but 10/24 of the patients in the other groups had symptoms. This study established the potential usefulness of secretin MRP in evaluating post-PD symptoms and demonstrated some correlation between the diarrhea/steatorrhea and partial or complete obstruction at the anastomosis. Obviously the ability to differentiate between stenosis at the pancreatico-jejunostomy anastomotic (PJA) and parenchymal hypofunction as the cause of symptoms would be useful in directing therapy.

Pessaux et al. combined secretin MRP and fecal elastase measurements in 19 patients who had had PD with pancreatogastrostomy [4]. Fecal elastase-1 was reduced in almost all patients possibly because of inactivation by gastric acid. Six of 19 patients had significant stenosis or obstruction at the PG and these had the lowest fecal elastase-1 levels. It is unclear whether any of the patients were symptomatic as a result of loss of exocrine function.

Nordback et al. investigated exocrine function in 26 patients who had pancreatic head resection including a few Beger procedures [5]. The anastomotic technique was a two layer invaginating anastomosis with the inner layer picking up duct wall. Patients were evaluated by dynamic MRP using secretin, 3–76 months postoperatively. Pancreatic function was evaluated by measurement of fecal elastase-1 concentration. More than 90 % of patients had severe exocrine insufficiency as assessed by fecal elastase-1 concentration. 66 % had moderate or severe diarrhea. The severity of diarrhea was associated only with a hard pancreas (usually associated with chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer) on multivariate analysis. 16 patients could have the anastomosis evaluated by dynamic MRP and these split almost evenly between total obstruction, partial obstruction, and patent anastomosis. The last had the highest fecal elastase-1 levels recorded. Not surprisingly, anastomosis to smaller ducts was associated with a higher incidence of obstruction. The authors conclude that pancreatic insufficiency under these circumstances is due to a combination of stenosis at the anastomosis and loss of functional parenchyma.

In summary, three studies in a limited number of patients using secretin MRP have described stenosis at the PJA or PGA in some patients. In two of these studies, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency was more prominent in the patients with greater degrees of stenosis and in two of the studies symptoms were also related. However, even patients with patency of the anastomosis usually have some degree of pancreatic insufficiency after PD that seems attributable to loss of parenchymal function. Variations in outcome of such studies are probably attributable to the underlying diagnosis, the time after PD that patients are studied, and whether symptomatic or asymptomatic patients are selected. Nonetheless, this seems to be a potentially fruitful area for future research particularly as endoscopic treatment of PJ strictures is improving and while stenosis of the PG or PJ is usually only one factor in exocrine insufficiency, it is potentially correctable.

Management of Intractable Pain Due to PJA or PGS Stenosis in Surgical Case Series

Several papers have described a small number of patients treated in some cases by operative means.

Reid-Lombardo et al. from the Mayo Clinic followed 122 patients who had PD for benign disease [6]. Selecting patients with benign disease allowed for long follow-up of the group and eliminated the possibility that symptoms were due to recurrence of cancer. Four required treatment for severe pain accompanied by exocrine insufficiency, and in one case pancreatitis accompanied by a pseudocyst for an incidence of 3 % and a cumulative probability rate over 5 years of 4.6 %. Three of the four patients presented in the 1st year after PD. Only one had had a PJA leak after PD. 40 % of the patients had PD for chronic pancreatitis and only one of these developed a stricture at the PJA. Two patients were treated surgically and two endoscopically. Pain was relieved in all four, as was steatorrhea in the three in whom it was present preoperatively.

Morgan et al. from the Medical University of South Carolina, in the largest case series on this subject, reported on 27/237 (11 %) patients who had revisional surgery for stricture at the PJA after PD for benign disease [7]. Their case series is notable for the very high percentage of patients who had PD for chronic pancreatitis—70 % of 237 patients. Also, 89 % of the 27 PJA strictures were in the patients with chronic pancreatitis. The predominance of patients with chronic pancreatitis is different from the reports of Reid-Lombardo et al. [6] and Demirgian et al. [8] (see below). The patients presented with intractable pain and pancreatitis at a mean of 12 months after PJ. Secretin MRP detected a stricture at the PJA in 18 patients. Nine other patients with normal imaging were diagnosed on the clinical grounds of pain and recurrent pancreatitis. Three patients had attempted treatment by ERP and all failed. All 27 had surgical revision of the anastomosis in most cases using the original jejunostomy limb. The pancreatic duct was opened on the anterior surface of a variable distance and reanastomosed to jejunum. There were no postoperative deaths but four patients died in long-term follow-up of causes not directly related to the revisional surgery. More concerning is that only 6 of the remaining 23 patients reported good relief of pain and two of these still used narcotic analgesics frequently. Also two of the patients with a good result were in the group of nine patients diagnosed only on the basis of symptoms (personal communication from first author).

Demirjian et al. described seven patients who developed PJS out of 357 PDs performed over 8 years [8]. 60 % of patients had PD for malignancy and 14 % for chronic pancreatitis. The incidence was 1.4 % in PDs done in their institution. Diagnosis was also by secretin MRP. Unlike the report from the Mayo Clinic, 6/7 patients had had a pancreatic fistula. On the other hand, there did not seem to be correlation to duct size or gland texture at the time of the PD. Only 2/49 cases (4 %) had had PD for chronic pancreatitis. Average time to presentation was more than 3 years. Endoscopic correction was attempted but failed in every case. Reconstruction was attempted in all. Four had reconstruction of the PJ after re-resection of the anastomosis and two had a lateral pancreatojejunostomy. In one case, the procedure was abandoned because of operative difficulty. In mean follow-up of about 2 years, 4/7 remained pain free of pain.

In summary, only a small number of case series regarding the surgical management of intractable pain due to stenosis at the PJA are available for review. The series are not particularly comparable as they differ in the type of patient studied (benign disease, mainly chronic pancreatitis and all patients having PD). Reoperation to correct stenosis at the PJA is technically difficult. It seems that it is less likely to be successful when it is performed in patients who have had PJA for the treatment of chronic pancreatitis. It is likely to be supplanted as first-line therapy by evolving endoscopic techniques (see below).

Pancreatico-Jejunostomy vs Pancreatico-Gastrectomy and Anastomotic Stricture

There have been a number of studies comparing these methods of anastomosis including some randomized trials, but most including the randomized trials have focused on the early results rather than comparisons of late outcomes such as strictures at the PJA vs PGA. Tomimaru et al. studied 42 patients 2 years after pancreatoduodenectomy, 28 who had had PGS and 14 who had had PJS [9]. They noted that pancreatic duct diameter tended to increase more and that pancreatic atrophy was more severe after PGS [9]. Schmidt et al. studied QOL after PGS and PJS at a mean time of 6.4 years after surgery in about 100 patients [10]. In the PG group, there was an increase in steatorrhea as well as intolerance to certain foods. There was no difference in need for enzyme replacement or in onset of diabetes, and global QOL was also not different in the two groups. Ishikawa et al. studied glucose tolerance in 51 patients over a 7-year period. The patients were about equally divided between PJS and PGS. The decline in glucose tolerance after PG was not associated with type of pancreatic anastomosis. Konishi performed a prospective randomized trial of PGS vs PJS and followed the patients for 2 years [11]. They found no difference in change of pancreatic duct diameter or glucose tolerance but the study population was made up of only 25 patients. These results address the problem of stricture only tangentially but they suggest that there probably is not an advantage of one type of anastomosis over the other in retention of pancreatic exocrine function. The data regarding pancreatic endocrine function are probably more reflective of remaining parenchyma than anastomotic stricture.

Endoscopic Techniques for Management of PJA Strictures

Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) has been the traditional endoscopic approach for treatment of symptomatic post pancreatoduodenectomy PJA strictures. It has had limited technical success. More recently, however, multiple additional novel techniques involving direct transgastric puncture of the pancreatic duct under endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) guidance have been described with much better technical and clinical success. In this section, we describe the various endoscopic techniques to treat symptomatic PJA stenoses, the obstacles involved, and the technical and clinical results.

Endoscopic Retrograde Pancreatography (ERP)

The traditional ERP approach involves accessing the pancreatojejunostomy anastomosis (PJA) retrograde through the afferent loop of the gastroenterostomy. There are several challenges involved in performing ERP through the afferent loop for treatment of PJA stenosis, which limit technical success.

First, successfully advancing the endoscope to the PJA is challenging. The afferent limb is often difficult to engage with the side-viewing duodenoscope. Also, the afferent limb may be of variable length (depending on surgeon preference and location of jejunal loop in relation to the transverse mesocolon), sometimes making it impossible to reach the PJA with a standard duodenoscope (124 cm long). In these situations, forward-viewing instruments are required, typically either a pediatric or adult colonoscope (168 cm long) or enteroscope (234 cm long) with or without a balloon overtube. Using a forward-viewing instrument poses several difficulties. First, these instruments lack an elevator, that is, a metal lever at the distal tip of the working channel that provides an extra degree of motion to instruments exiting the tip of the scope. Second, the longer working channel length of colonoscopes and enteroscopes compared to duodenoscopes limits the number and type of instruments, which can be utilized during the procedure. Third, pediatric colonoscopes and enteroscopes have smaller diameter working channels, which limits the caliber of stents that can be used.

The second major difficulty encountered is that a stenotic PJA can be difficult to visualize (Fig. 24.2 ). The PJA is usually 15–20 cm beyond the usually well-visualized choledochojejunostomy and can be located at the stump of the afferent limb or, more commonly, approximately 5 cm proximal to the stump. Visualization of the anastomosis also depends on whether it is an end-to-end or end-to-side anastomosis, the latter being usually more difficult to visualize. When the PJA cannot be visualized, there are ways to help localize it. One method is to administer intravenous secretin and observe for a gush or trickle of pancreatic juice. However, another challenge is transparency of pancreatic juice. Visualization of the juice can be enhanced by spraying the mucosa with a dye, such as methylene blue.

Fig. 24.2

Close-up endoscopic view of a stenotic pancreatojejunal anastomosis ( box). This was located behind a fold. The estimated diameter is 1 mm. (Courtesy of Susana Gonzalez, MD)

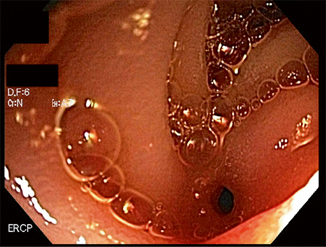

Once the PJA is identified, a variety of catheters and wires may be utilized to achieve deep cannulation of the pancreatic duct. Usually, due to the pinhole size of the PJA, the smallest available 3-4-5 F taper tip catheter loaded with an 0.021ʺ caliber wire is used. Once the PJA is carefully engaged with the catheter, contrast is injected and retrograde opacification of the pancreatic duct is observed fluoroscopically. The wire is then advanced deeply into the pancreatic duct. Another approach is to attempt passage of a wire through the anastomosis prior to injection of contrast. Following wire placement deep into the pancreatic duct (Fig. 24.3 ), passage or balloon dilation of the PJA is performed. Cautery is avoided to reduce the risk of perforation at the PJA. Following dilation, a plastic stent is placed (Fig. 24.4 ). There are multiple different stent types of varying lengths, diameters, and shape (straight versus pigtail). Generally, stents are removed in 6 weeks, and the need for repeat dilation or stenting is assessed at that time (Fig. 24.5 ). However, the optimal duration of stenting is not well established and not evidence based.

Fig. 24.3

Retrograde pancreatogram reveals a mildly dilated and irregular main pancreatic duct and a stenotic PJA ( arrow). A guidewire is then inserted through the stenotic PJA into the pancreatic duct over which balloon dilation and stent placement can be performed. (Courtesy of Susana Gonzalez, MD)

Fig. 24.4

A transanastomotic 5 F plastic stent has been placed into the pancreatic duct ( double arrow). The intraluminal portion of the stent has a pigtail to prevent migration into the pancreatic duct ( arrow). (Courtesy of Susana Gonzalez, MD)

Fig. 24.5

Widely patent pancreatojejunostomy following stent placement. (Courtesy of Susana Gonzalez, MD)

Technical Clinical Results for ERP

Given the limitations described above, technical success rates of ERP for treating PJA strictures are low. Farrell et al. described their technical success with ERCP in 29 patients who were postpancreatoduodenectomy [12]. The afferent limb was successfully intubated in 92 % of cases. Among these patients, ten had pain attributed to a stenotic PJA. Within this group, successful identification of the PJA was achieved in five patients (50 %), three of which had PJA stenosis and underwent stenting with palliation of pain. Chahal et al. reported their experience in 51 patients with pancreatoduodenectomy anatomy [13]. Among the 37 patients in this series undergoing ERCP for pancreatic indications, technical success was achieved in only three (8 %). Technical success in both series was much higher for biliary indications at approximately 80 %. Long-term clinical outcomes regarding palliation of pain and incidence of restenosis were not provided.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree