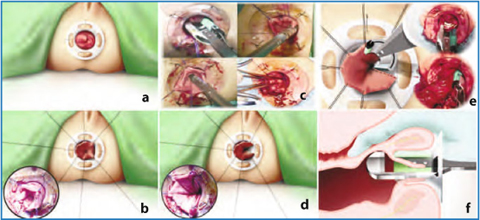

Fig 14.1

STARR technique. a Rectal prolapse evaluated by exposing it through the circular anal dilator with a mounted gauze swab. b Three separate one-half (180°) purse-string sutures are made to include the mucosa, submucosa, and rectal muscle wall, 1–2 cm above the apex of the hemorrhoidal ring. c The staple line is carefully inspected and eventually reinforced using reabsorbable 2-0/3-0 stitches at the end of the resection of the anterior rectal wall and subsequently after the resection of the posterior wall

Starting from the anterior rectal wall, the posterior wall must be protected by a retractor inserted in the anal canal through the lower hole of the CAD.

By introducing the purse-string anoscope in the CAD, three separate one-half (180°) purse-string sutures can be made, including the mucosa, submucosa, and rectal muscle wall, 1–2 cm above the apex of hemorrhoidal ring, in order to include both the top of the rectocele and the internal rectal prolapsed tissue (Fig. 14.1b). Polypropylene 2-0 sutures are usually used.

The opened circular stapler should be inserted into the anal canal through the CAD, with the anvil placed above the purse-strings. By using traction on the purse-strings, the prolapsed tissue is brought into the housing when closing the stapler. During this maneuver the posterior vaginal wall should be carefully inspected in order to avoid its entrapment in the staple line. Sometimes a minimal mucosal bridge left between the two edges of the anastomosis and can be removed with scissors.

At the end of the first resection, the staple line should be carefully inspected and eventually reinforced by using reabsorbable 2-0/3-0 stitches (Fig. 14.1c). This also to improve hemostasis.

The same procedure should be repeated for the posterior rectal wall. The retractor should now be inserted into the upper hole of the CAD.

The so-called “dog ear”, a protuberance that remains at the lateral intersections of the staple lines at the end of the procedure, should be oversewn.

14.3.2 Safety and Efficacy

Since its introduction, several studies have been conducted to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of STARR [9–11].

According to the data reported by the Italian, German, and European STARR registries, STARR is a safe procedure with a morbidity rate of 34% [5–7]. The most common reported complication is defecatory urgency, which affects 20–25% of patients. Although it is present in more than one-fifth of patients, the defecatory urgency tends to resolve spontaneously within a few weeks, with a very low percentage of patients continuing to have symptoms after 1 year [4–11].

Postoperative persistent pain is another complication of STARR. This complication has been reported with variable incidence (0.5–7%) in the various series described in the literature [5–11]. The pain seems to be mainly related to mistakes in surgical technique, such as the inappropriate placement of a low staple line. This is because different surgeons have different levels of familiarity with stapled-aided colonproctology techniques.

Less common, but always present in the various case series, is postoperative bleeding. This is reported in 5% of patients and often requires a reintervention [4–7].

Other complications include staple line complications (minor bleeding, infection, or partial dehiscence), fecal incontinence, septic events, and postsurgical stenosis; these occur in a small minority of patients [5–11]. Acute urinary retention reported by some authors seems to be more related to subarachnoid anesthesia rather than surgical technique [5–11].

Rectovaginal fistula, dyspareunia, and rectal necrosis are extremely uncommon, and only a few single cases have been reported [5–11].

The effectiveness of STARR in the treatment of ODS has been demonstrated by several studies [5–11]. The European STARR registry showed that symptoms of ODS were reduced after 12 months in 2,224 (78%) of 2,838 patients treated by STARR [6].

Also, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recently recognized the efficacy of STARR, but stressed that, although there are limited data on this procedure, there are particularly good-quality comparative data and studies reporting on long-term outcomes [12].

Only a few trials with a median follow-up of more than 1 year have been reported. These, despite the small number of enrolled patients, appear to confirm good results for STARR in the correction of rectocele and rectal prolapse, with only a small percentage of patients reporting a worsening of symptoms [13–15].

Of note is a recently published randomized controlled trial that showed an advantage in terms of reduced intraoperative bleeding and operative time with the use of PPH03 instead of PPH01 (Ethicon EndoSurgery) [16].

Recently, the introduction of newly circular staplers with a more spacious housing, also called “high-volume circular staplers”, may be able improve the results of STARR, but no good-quality data or comparative studies are yet available on the use of these devices [17].

14.4 TRANSTARR

14.4.1 Surgical Technique

Bowel-rectum preparation and antibiotic prophylaxis are recommended before this procedure. The patient should be in the lithotomy position and under general or spinal anesthesia.

The first step is the introduction of a CAD after careful dilatation of the anal verge with the obturator provided in the TRANSTARR kit. The surgeon must check that the dentate line is protected directly below the anal dilator. The CAD must be secured to the perianal skin with four stitches at 2, 4, 8 and 10 o’clock (Fig. 14.2a).

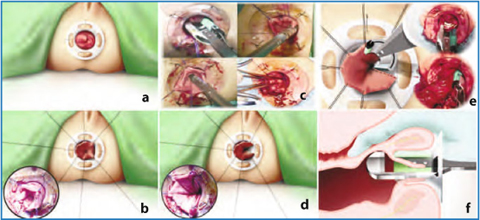

Fig. 14.2

TRANSTARR technique. a A circular anal dilator is introduced and secured to perianal skin with four stitches at 2, 4, 8 and 10 o’clock. b 4–5 polypropylene 2-0 sutures are placed in the form of parachute cords to control the prolapse during the resection. c Longitudinal opening of the prolapse with one firing of the Transtar CCS-30, with a linear stapler or between two Kocher clamps. d Rectal prolapse opened longitudinally. e Circumferential rectal resection with the Contour Transtar. f The posterior vaginal wall is inspected with a finger during the resection of the anterior rectal wall to prevent its entrapment in the staple line, as this can result in formation of a rectovaginal fistula

The prolapsed tissue should be pulled gently out through the CAD using a gauze pad and Allis forceps to evaluate the extent of the prolapse and assess the amount of tissue to be resected.

With the aid of the Allis forceps, the rectal wall should be unfolded to expose the apex of the prolapse in order to place 4–5 polypropylene 2-0 stitches, resembling parachute cords (Fig. 14.2b). The sutures must be positioned with two or three full-thickness bites to gain a solid traction on the prolapse. This maneuver must be performed with the use of the access suture anoscope provided with theTRANSTARR kit, being careful not to inadvertently catch some tissue from the opposite rectal wall or the vagina. These stitches allow the surgeon to achieve symmetrical traction of the prolapse around its circumference and to obtain good tissue control during resection.

The initial step provides a longitudinal opening of the prolapse with one firing of the CCS-30 Transtar (Fig. 14.2c). However, in presence of a large prolapse, this is not always easy and it often makes the loading of the prolapsed tissue between stapler jaws more difficult because of the presence of an irregular staple line or bundled tissue. To overcome this, it has been proposed that the prolapse be opened longitudinally with a linear stapler (but this increases the cost of the procedure), or by using two Kocher clamps placed at 2 and 4 o’clock to grab the prolapsed tissue, and then opening the prolapse with a cautery between the clamps (Fig. 14.2c, d) [18, 19].

Another one or two polypropylene 2-0 stitches should be placed on both sides of the deep vertex of the prolapse opening, to handle the prolapse during its insertion between the CCS-30 jaws for the first transverse firing. These stitches also act as a reference for the start and end-points of the circumferential resection, allowing the surgeon to prevent spiraling of the staple line. In fact, if the stapler is not well positioned at the bottom of the prolapse opening or it is not perpendicular to the rectum, an irregular or spiraling resection will result, thereby increasing the risk of complications. Using traction on the parachute stitches, it is then possible to start the circumferential rectal resection (Fig. 14.2e).

This maneuver is performed counterclockwise by ensuring that the stapler is placed at the base of the prolapse and perpendicular to the CAD. It is important not to bundle the tissue between the stapler jaws and to maintain the stapler at the same depth, using the CAD as a reference, to reduce the risk of spiraling and the formation of dog ears at the beginning and end of the mechanical suture. During the resection of the anterior rectal wall, the surgeon must be careful not to entrap the posterior vaginal wall in the suture, which can result in formation of a rectovaginal fistula (Fig. 14.2f). This can be achieved by pulling the posterior vaginal wall upward, and inspecting the vagina before firing the stapler.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree