Starr

David Jayne

Antonio Longo

Introduction

Stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) was described in 2001 as a new technique for the treatment of obstructed defecation associated with distal rectal prolapse (rectocele, intussusception, mucohemorrhoidal prolapse). The original technique involved a double-stapling procedure using two PPH-01® staplers (Ethicon Endosurgery, Europe) to produce a circumferential, full-thickness rectal resection. This technique is referred to as PPH-STARR, or simply STARR. More recently, a reloadable-stapling device specifically designed for STARR has been introduced, the Contour30® Transtar (Ethicon Endosurgery), which allows a sequential full-thickness circumferential rectal resection to be performed. This procedure is referred to as Transtar to distinguish it from PPH-STARR and is described in a subsequent chapter.

Indications

STARR is advocated as a treatment option for patients suffering from obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) because of defined anatomical defects of the distal, subperitoneal rectum. These anatomical defects are readily appreciated on dynamic pelvic floor imaging, by either defecography or magnetic resonance imaging, as a redundancy of the distal rectum, which forms a mechanical obstruction impeding effective rectal evacuation. Most commonly, the mechanical obstruction manifests as a combination of the following:

rectocele

distal rectal intussusception

mucohemorrhoidal prolapse

Frequently, pathological descent of the perineum is present. In 30–40% of cases there will be coexistent other pelvic organ prolapse, which may include enterocele, sigmoidocele, and/or urogenital prolapse. Awareness of other pelvic floor pathology is important is ensuring correct patient selection and maximizing postoperative outcomes.

Whether STARR is of benefit in patients with anismus (pelvic floor dyssynergia) with coexisting rectal redundancy is controversial (1). A trial of conservative treatment with biofeedback therapy, and possibly combining botulinum toxin, should be considered before contemplating STARR.

Contraindications

The following absolute and relative contraindications have been suggested for STARR (2):

Absolute contraindications:

active anorectal sepsis (abscess, fistula, etc.)

concurrent anorectal pathology, including anal stenosis

proctitis (inflammatory bowel disease, radiation proctitis)

chronic diarrhea

Relative contraindications:

presence of foreign material adjacent to the rectum (such as prosthetic mesh from a previous rectocele repair or pelvic floor resuspension)

previous anterior resection or transanal surgery with rectal anastomosis

concurrent psychiatric disorder

There has been much debate about the role of enteroceles in obstructed defecation and whether they precluded treatment with STARR. Initial concerns regarding iatrogenic injury to the small bowel have proven to be unjustified. Current opinion is that STARR is safe in the presence of an enterocele provided appropriate precautions are taken. If doubt remains, laparoscopic reduction of the small bowel can be performed at the same time as STARR (3).

Patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome are a difficult group in whom to predict outcome. Provided mechanical outlet obstruction can be demonstrated on dynamic imaging then STARR may be a reasonable option.

Caution should also be exercised in patients with documented anal sphincter dysfunction. Although defecatory urgency is a recognized feature in approximately 20–40% of patients with ODS, there is a definite incidence of de novo urgency that follows STARR. The exact mechanism for this is unclear, but in the majority of cases it is self-limiting with resolution within 6–12 weeks. It is probable that it is those patients with preexisting anal sphincter dysfunction who are most vulnerable to this complication, and should be appropriately counseled if STARR is considered.

All patients presenting with ODS should have their symptoms quantified using a validated scoring system (4,5). Any history of transanal surgery or obstetric trauma should be documented, and a clinical examination should be performed to assess anal sphincter function, document the presence of rectocele and intussusception, and to exclude other anorectal pathology. Examination of the urogenital organs, preferably in conjunction with a urogynecologist, should be undertaken if relevant symptoms are present. The presence of rectal redundancy, with internal prolapse with or without rectocele, should be verified by dynamic pelvic floor imaging in the form of defecography or dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. If anal sphincter dysfunction is suspected, either on history or on examination, formal evaluation by anorectal manometry, anal electromyography, and endoanal ultrasound is recommended.

STARR can be performed under either spinal or general anesthesia. The lower bowel should be prepared by administration of a phosphate enema to ensure that the rectum

is empty. The patient is placed on the operating table in the supine position. The legs are supported in stirrups with the hips flexed to at least 90 degrees and the table tilted to 30 degree head-down for maximal exposure of the perineum. A single dose of broad-spectrum perioperative antibiotics is administered. An examination under anesthesia is performed to confirm the presence of internal prolapse with or without rectocele and to exclude coexistent pathology and other pelvic organ prolapse.

is empty. The patient is placed on the operating table in the supine position. The legs are supported in stirrups with the hips flexed to at least 90 degrees and the table tilted to 30 degree head-down for maximal exposure of the perineum. A single dose of broad-spectrum perioperative antibiotics is administered. An examination under anesthesia is performed to confirm the presence of internal prolapse with or without rectocele and to exclude coexistent pathology and other pelvic organ prolapse.

The following describes the steps involved in the double-stapled PPH-01 STARR procedure:

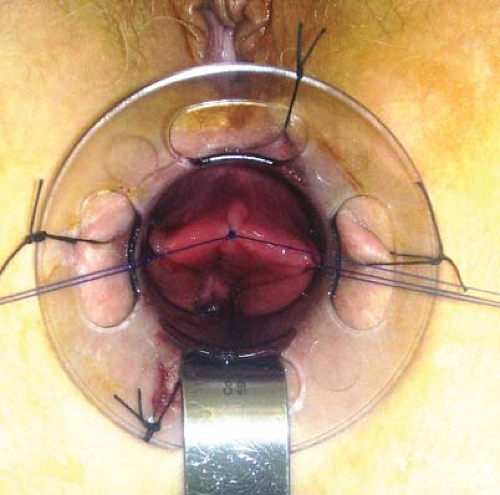

Four 1/0 silk sutures are placed at the anal verge in the 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock positions. Applying traction on the sutures, the anal canal is gently dilated with the anal dilator, following which the CAD33 is introduced and secured at the anal verge with the sutures.

The apex of the prolapse is identified with a dry swab inserted into the rectum and then withdrawn. Three 2/0 prolene traction sutures are placed at the 10, 12, and 2 o’clock positions. The two ends of the 12 o’clock suture are separated and one each tied with the 10 and 2 o’clock sutures such that in total two traction sutures are used to deliver the internal prolapse. A spatula is inserted into the anorectum at the 6 o’clock position between the posterior lip of the CAD33 and the anal canal to exclude the posterior anorectum (Fig. 26.1).

A fully opened PPH-01 stapler is inserted into the rectum such that its anvil lies beyond the area of prolapse. The two traction sutures are passed through the lateral channels in the stapler and are used to deliver the prolapse into the stapler housing. Keeping the stapler in line with the anal canal at all times, the stapler is closed. A digital vaginal examination is performed to ensure that the vaginal wall has not been inadvertently incorporated into the stapler. Thirty seconds is allowed for tissue compression before firing the stapler.

The stapler is opened by one half-turn of the opening mechanism and withdrawn. The resected specimen is retrieved from the stapler housing and should include a full-thickness resection of the anterior rectum (Fig. 26.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree