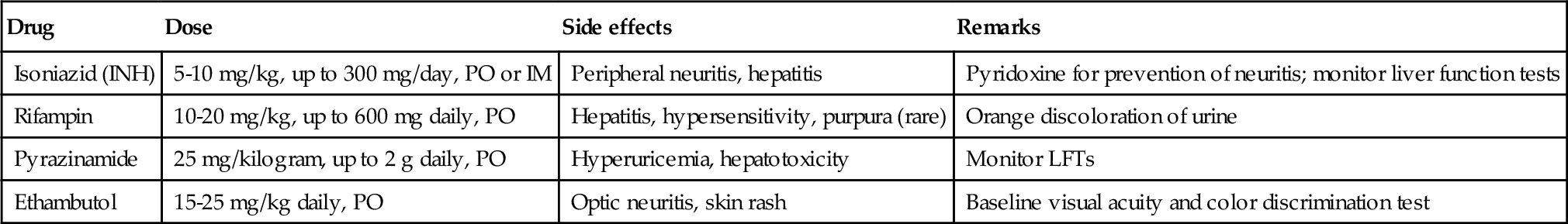

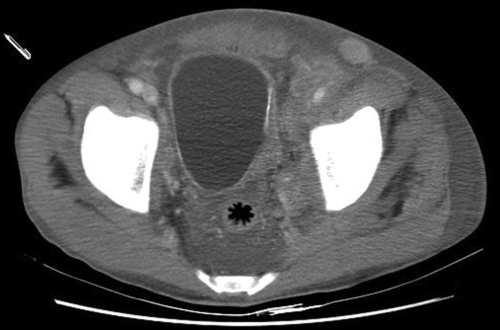

Chapter 5 • Tuberculosis (consumption) reached epidemic proportions in 18th century Europe. Signs of the disease have even been found in mummies dating back to 3000 BCE. • The bacillus causing tuberculosis was identified by Robert Koch in 1882. • Once infected, 5% to 10% of patients exposed to TB will develop active disease in their lifetime. Those with compromised immune systems are at higher risk to become symptomatic. • The largest number of new cases occurs in Asia, but the highest per capita incidence of new TB cases is in sub-Saharan Africa. • In 2011, 1.4 million persons died of tuberculosis; over 95% of deaths occurred in developing nations. • TB is a major cause of mortality in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), causing one fourth of all deaths. Tuberculosis is the most important opportunistic infection in this patient group. • One third of the world’s population has latent TB. Those who are not ill generally cannot transmit the disease. • The genitourinary tract is the second most common extrapulmonary site of involvement, after lymph nodes. Active genitourinary TB presents 5 to 25 years after initial infection. • Host immunity largely determines whether infection occurs or is eliminated at the initial exposure. If not eliminated, mycobacteria then slowly divide within alveolar macrophages, and it takes several weeks before a cellular immune response is mounted. Before the host immune system can limit or destroy the bacteria, hematogenous spread can occur. • Medlar proved in 1949 that the infection spreads from the lungs to the renal cortex by hematogenous dissemination. The kidney is usually the primary organ infected. The renal cortex is favored because of higher oxygen availability. Other parts of the GU tract become involved by direct extension. • Primary sites of genital tract disease include the epididymis in males and the fallopian tubes in females. • At infected foci, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts aggregate to form a granuloma around the bacilli, but the organisms may remain viable and become dormant within the tubercle, resulting in latent infection. • Involved sites may remain dormant for many years, then reactivate and spread by caseation and cavitation. Factors favoring reactivation include diabetes, HIV, malignancy, chemotherapy, or immunosuppressant medications. • Tubercles in the glomeruli may cause parenchymal destruction, then spread into the medulla and result in papillary necrosis or cavitation. Bacilli then enter the urine and travel down to the ureters and bladder. The bacilli in the ureters can cause fibrosis resulting in ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction, ureteral stricture, and bladder inflammation and contracture. • From the lower urinary tract, passage of infected urine into the genital ducts then leads to involvement of the prostate, seminal vesicles, vas deferens, epididymis, and testicle. • Genitourinary TB can also arise from infection and dissemination of attenuated bacilli during intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) therapy for treatment of urothelial carcinoma. In rare cases miliary TB has been reported as a complication of BCG instillation. • Renal involvement may be silent, with only nonspecific symptoms; cases of GU tuberculosis can thus be easily overlooked. • Symptomatic GU tuberculosis is more common in males (2:1), and the earliest signs of infection may be tuberculous epididymitis or cystitis. • Granulomatous prostatitis may occur and is also seen following intravesical therapy with BCG. • Female genital TB can present as infertility, nonspecific pelvic pain, or menstrual alterations. Fallopian tubes are involved in 95% of women with genital TB, where the disease may then spread to the peritoneum. • Definitive diagnosis involves demonstration of mycobacterial organisms in urine culture or histopathologic examination of a biopsied granulomatous lesion. • Majority of patients present with “sterile pyuria”; 20% may have superimposed bacterial infections. • Three to five early-morning urine specimens are preferred because excretion of the organism may be sporadic. Incubation of urine cultures for up to 1 week is required to visualize early colonies on agar-based culture media. • Cultures are essential to determine antibiotic sensitivity but may take up to 6 to 8 weeks. • Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based nucleic acid amplification tests of the urine are reliable, specific, and provide rapid results in diagnosis of tuberculosis. There is a 10% false negative rate. These assays are best used in conjunction with cultures and clinical symptoms to confirm the diagnosis of genitourinary TB. • The Mantoux PPD (purified protein derivative) tuberculin skin test, which is based on a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to intradermal injected antigen, is useful when positive, and a negative TB tine test makes the diagnosis unlikely. • Radiographic findings in genitourinary TB are nonspecific but are important to evaluate extent of disease. Plain radiographs (kidneys-ureters-bladder [KUB], chest x-ray) may show calcification. Intravenous pyelogram (IVP) or computed tomography (CT) urography can demonstrate parenchymal destruction and assess for obstruction. CT imaging can also identify adrenal involvement (5% of active TB cases). • In patients with genitourinary TB, 50% to 75% have chest radiographs that show old or active pulmonary disease. • Cystoscopy is rarely indicated for diagnostic purposes but may be needed to rule out malignancy. Bladder biopsy can cause dissemination of the disease in patients who are not on antituberculous therapy. • Drug sensitive TB is treated with a standard 6-month course, starting with four antimicrobial agents for 1 to 2 months. Then an additional 4 months of rifampin and isoniazid (INH) are used. • Surgical intervention may be necessary for treatment of obstructing lesions or removal of infected tissue (e.g., nonfunctioning renal unit) but should be deferred for 4 to 6 weeks after starting medical therapy. • Supervised, directly observed administration of the medications is recommended to ensure compliance. • Reevaluation with cultures is recommended 3, 6, and 12 months after completion of therapy, with appropriate imaging studies in patients with genitourinary involvement. • Multidrug-resistant TB is most often treatable and can be cured with use of second-line agents. 2. Primary agents include INH, rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol (Table 5-1). Pyridoxine (vitamin B6, 10 to 50 mg daily) should be taken with regimens that include INH to prevent central nervous system (CNS) effects and peripheral neuropathy. 3. Second-line agents include aminoglycosides (streptomycin, capreomycin, kanamycin, amikacin), cycloserine, ethionamide, fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin [Avelox]), aminosalicylic acid, and protionamide. • There are four species of Schistosoma that can cause human infection. Schistosoma hematobium is the pathogen responsible for urinary schistosomiasis, with paired adult worms residing in the perivesical venules. • Genitourinary schistosomiasis is endemic to Africa and the Middle East. • GU infection by S. hematobium leads to hematuria, hydronephrosis, and carcinoma of the bladder. Affected females may have cervicitis and vaginitis, and late manifestations of the female genital tract include infertility and ectopic pregnancy. • The urinary bladder develops sandy “patches” containing schistosome eggs; later in the infection, calcification of these patches occurs. The presence of a calcified bladder on plain radiograph or CT is diagnostic of chronic urinary schistosomiasis (see Figure 5-1). • Larvae migrate through the body and mature into adult male and female worms. The worms, 1 to 2 cm in length, pair and reside in the vesical venules. The female releases 200 to 300 eggs per day into the submucosa of the bladder, a process that can continue for several years. Some of the eggs are excreted in the urine to complete the life cycle, returning to water and the intermediate snail host. • The ova deposited into the bladder submucosa produce an intense inflammatory reaction. • Diagnosis of schistosomiasis can be made by observing schistosome ova in the urine. Terminally spined eggs found in the urine sediment are pathognomonic of S. hematobium, and this remains the gold standard for diagnosis of active infection. • Rectal or bladder biopsy can also be performed for diagnostic purposes. • Serology tests are also available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention but cannot distinguish between previous exposure and acute or chronic infection. • Imaging studies are important to assess for possible obstruction. • Initial contact with cercariae can produce intense pruritus (swimmer’s itch). • After larvae gain access to the systemic circulation, symptoms include fever, cough, malaise, and myalgia. Heavy inoculation can rarely produce a serum sicknesslike syndrome that can be fatal. • Most human hosts become chronically infected, and female worms may produce eggs for years, causing slowly progressive disease. • The eggs elicit a granulomatous inflammatory response that accounts for the typical initial symptoms of painful terminal hematuria, dysuria, hematospermia, and irritative voiding symptoms. • Schistosomal bladder polyps, secondary infection (often by Salmonella

Specific Infections of the Genitourinary Tract

Genitourinary tuberculosis

General considerations: scope of the disease

Pathogenesis

Clinical manifestations and diagnosis

Therapy

Genitourinary schistosomiasis

General considerations

Etiology and pathogenesis

Clinical features

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree