Colonic ulcerations can affect the entire colon and rectum, and have variable clinical presentation according to the anatomic location and underlying pathology. Diverse causes may lead to colonic ulceration, such as inflammatory bowel diseases, oral drugs (mostly nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), local or diffuse ischemia, and different intestinal microorganisms. An ulcer may also herald a concealed malignant disease. In most cases, colonic ulcerate is associated with diffuse colitis in the acute setup or with inflammatory bowel diseases, and to the lesser extent the ulceration is defined as solitary. This article focuses on two of the less commonly diagnosed diseases: solitary rectal ulcer syndrome and stercoral ulceration, both related to local tissue ischemia and often seen in the elderly population.

Colonic ulcerations can affect the entire colon and rectum. These ulcerations have variable clinical presentation according to the anatomic location and underlying pathology. Diverse etiologies may lead to colonic ulceration, for example, inflammatory bowel diseases, oral drugs (mostly nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), local or diffuse ischemia, and different intestinal microorganisms. An ulcer may also herald a concealed malignant disease. In most cases, colonic ulceration is associated with diffuse colitis in the acute setup or with inflammatory bowel diseases, and to a lesser extent the ulceration is defined as solitary. This article focuses on two of the less commonly diagnosed diseases: solitary rectal ulcer syndrome and stercoral ulceration, both related to local tissue ischemia and often seen in the elderly population.

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS), as the name implies, consists of several different clinical pathologic processes. These processes, however, end in a mutual common pathway that is associated with reduced blood perfusion of the rectal mucosa, leading to local ischemia and ulceration. SRUS was described in the early nineteenth century by the French anatomist J. Cruvilhier in his report on chronic rectal ulcer. However, the distinctive histopathologic characteristics were defined in 1969 by Madigan and Morson. SRUS is a rare syndrome with a prevalence of less than 1 in 100,000 per year. The current literature comprises case series studies and sporadic case reports.

Clinical Presentation

Due to its rarity, nonspecific signs, and symptoms and various causes, SRUS diagnosis is delayed in many cases. However, chronic constipation, strenuous defecation, bloody and mucous secretions per rectum, and nonspecific pelvic pain are the major complaints encountered by physicians.

Diagnosis

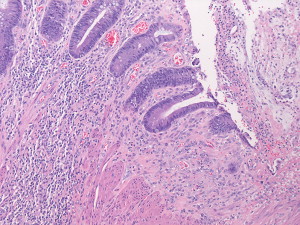

In many cases the initial clinical workup includes endoscopic visualization of the colon, revealing a solitary ulcer on the anterior rectal wall from which biopsies should be taken to rule out a malignant disease. Despite the diverse causes the microscopic changes are analogous, comprising fibromuscular obliteration and disorientation of the muscularis mucosa ( Fig. 1 ).

Etiology

As mentioned earlier, the underlying cause for this type of ulceration is chronic local ischemia of the colonic wall. Although the gradual sequence of this pathology may originate for various reasons, SRUS has been related to several independent clinical settings.

Rectal prolapse and intussusception

Rectal intussusception, which may lead to full-thickness rectal prolapse, results in localized vascular trauma and ischemia, initiating solitary local ulceration.

Paradoxic contraction of the pelvic floor muscles

This uncoordinated sequence of muscle contraction and relaxation required for the defecation process, also called puborectalis syndrome or pelvic outlet obstruction, causes increased pressure inside the rectum and anal canal, generating ischemia and ulceration.

Trauma

Localized rectal trauma, mainly from digitation or self-instrumentation, has been proposed as one of the causes of SRUS. Supportive evidence for anal intercourse as a basis for rectal ulceration do exist; however, conflicting conclusions have been published as well.

Extraneous defecation due to chronic constipation and hard stool mimics the pathogenesis of outlet obstruction when high pressure chronically reduces the mucosal blood flow in the rectum aside from local mechanical-induced tears.

Radiotherapy and ergotamine suppositories

Further supportive evidence for the substantial role of mucosal perfusion and ischemia in the pathogenesis of SRUS is the use of ergotamine suppositories. These strong vasoconstrictors, indicated for treating severe migraine, have been shown to induce local ischemia and ulceration. Radiotherapy, which in the long term affects permanently small blood vessels, has been cited as potentially antecedent to SRUS as well.

Treatment

Because the etiology of SRUS is diverse, the therapeutic approach is variable. After the diagnosis is reached, usually by direct endoscopy and pathology results from biopsies that ruled out malignancy, the next diagnostic step is detecting the underlying pathologic basis of disease. Thorough history-taking to rule out local trauma or behavioral patterns and how to avoid these may be the initial treatment. Further imaging and physiologic studies are usually indicated, including rectal ultrasound, cinedefecography, and contrast enema. These procedures indicate muscle relaxation-related pathologies as well as other mechanical disorders.

Local treatments with steroid or sulfasalazine enemas were not effective in all patients, whereas using a fibrin sealant achieved good results in six patients followed for 1 year. For some underlying pathologies conservative measures such as stool softeners, adequate daily water intake, and cessation of digitation, or stopping the use of relevant suppositories address the clinical signs and symptoms. However, when pelvic outlet obstruction is the source of local ischemia the therapeutic aspects should focus on biofeedback training sessions, educating the patient to control the proper muscle contraction and relaxation sequence.

In some cases when rectal prolapse is diagnosed, surgical intervention is indicated. Choosing the correct surgery, which may vary from a resection using the perineal approach to abdominal operation or even a permanent colostomy, should be made independently for each patient.

Outcomes

Depending on the underlying cause and the chosen treatment, the therapeutic outcomes varies. Several studies of a low volume of patients and short follow-up, describe the outcome of different solutions for patients diagnosed with SRUS. When seven patients were treated by biofeedback alone for symptomatic puborectalis syndrome, an improvement in the symptoms was noted with a follow-up of 6 months. In another series of 13 patients, improvement was documented on clinical symptoms and on quality of life. However, among the 9 patients examined after the treatment the ulceration did not heal completely. Sitzler and colleagues reported the long-term surgical outcomes of 66 patients who underwent 72 procedures for SRUS. This study revealed improvement among 52% of the patients who did not have a colostomy.

Conclusions

SRUS is the final clinical outcome of different pathologic settings associated with compromised perfusion to the rectal mucosa. Identifying the correct foundation allows proper treatment with optimal results.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree