Colonic diverticulosis is a common, usually asymptomatic, entity of Western countries, with an incidence that increases with age. When these diverticula become infected and inflamed, patients can present with a wide variety of clinical manifestations. Management of acute, uncomplicated diverticulitis can often be treated successfully with antibiotics alone and the decision to proceed with more aggressive measures such as surgical intervention is made on a case-by-case basis. The treatment algorithm for diverticular disease continues to evolve as the pathophysiology, etiology, and natural history of the disease becomes better understood.

Colonic diverticulosis is mainly an asymptomatic disease of Western countries, which first began to be recognized as a widespread problem in the 20th century. Infection and inflammation of these diverticula was first described in the late 1890s by Graser and later linked to the clinical symptoms in the early 1900s by Beer. Most colonic diverticula are acquired, with the incidence increasing with age. Less than 2% of patients younger than 30 years old have diverticulosis, whereas more than 40% of patients older than 60, and 60% by age 80 years, acquire diverticula. It is estimated that 10% to 25% of patients with diverticulosis go on to develop diverticulitis. In the United States this results in approximately 130,000 hospitalizations per year and significant cost to the health care system.

In 95% of cases, diverticula are located in the sigmoid and left colon. Right-sided colonic diverticula are rare in Western countries, although with increasing age there is a tendency for the diverticula to not only increase in number but also to develop more proximally in the colon. In Asian countries, the main distribution of diverticula (up to 70%) is right-sided and may have a more genetic influence.

The clinical picture for diverticulitis is one defined by a spectrum of presentations. Patients can present with a mild, isolated attack or can have severe and recurrent disease. In addition, a subset of patients present with complicated disease and some have “smoldering” disease. A new disease entity known as SCAD (Segmental Colitis Associated with Diverticula) has been described recently and may involve a different pathophysiology than classic diverticulitis.

Not only has the etiology of diverticulitis become more complex than previously believed but the treatment algorithms have also evolved. The main components of treatment historically have been antibiotics and surgery. Less invasive nonsurgical procedures, along with new data suggesting the disease may not be as virulent as once believed, have recently questioned some of the surgical dogma that has guided treatment for many years.

Pathophysiology and etiology

Diverticula of the colon are not true diverticula (involving all three layers of the colonic wall) but pseudodiverticula, in which only herniation of the mucosal and submucosal layers is present. Despite being commonly seen and treated, the exact etiology of diverticular disease remains unknown. The Industrial Revolution brought with it “roller milling,” which removed up to two-thirds of the fiber content in foods, and the decrease in dietary fiber seen during this period correlates well with the beginning of symptomatic diverticular disease. This led to wide support of the theory that lack of dietary fiber is the main cause of diverticulosis.

A host of anatomic factors may work in conjunction with increased intraluminal pressures to lead to the pathogenesis of diverticula. Unlike other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, the colon is unique in that the outer muscular layer does not completely envelop it. The outer muscle layers coalesce to form 3 distinct bands, the taeniae coli, which run along the length of the colon. In addition, there are intrinsic weaknesses in the colon wall that develop where the vasa recta penetrate. The development of diverticula most commonly occurs along the mesenteric border of the antimesenteric taeniae, which corresponds to where the vasa recta are closest to the mesentery.

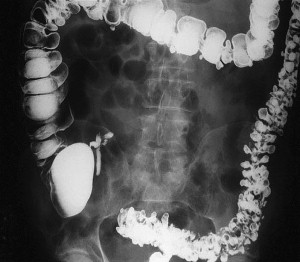

Another structural difference in the colon of patients with diverticular disease relates to the thickness of the colon and the fact that collagen cross-linking increases with age. This may in part explain why pan-diverticular disease develops in some patients ( Fig. 1 ). It was initially believed that the colon became thickened with diverticular disease because of hypertrophy. On the contrary, follow-up studies revealed that microscopically there was no evidence of hypertrophy and that the changes were secondary to increased deposition of elastin. This deposition results in highly contractile normal muscle, contributing to the increased luminal pressures. In addition, it has been shown that the amount of collagen cross-linking increases with age, especially in individuals older than 40 years. As the cross-linking increases, the colon becomes more rigid, losing the compliance that is necessary to accommodate the increased pressures.

Segmentation is a phenomenon that occurs in the colon that leads to formation of isolated areas of extremely high intraluminal pressure. Segmentation occurs when two haustra that are near each other contract simultaneously and create a short segment of colon that is essentially a closed loop, leading to high pressures. This condition, along with studies demonstrating colonic hypermotility in the setting of diverticular disease, suggests that motility has some impact on the development of diverticula.

The interplay of colonic wall structure, colonic motility, and the amount of dietary fiber likely leads to the formation of diverticula in the colon. The etiology of why inflammation of the diverticula occurs and diverticulitis develops is not well understood. Symptoms from diverticulitis occur when there is microperforation or free perforation of a diverticulum. Following this event variable amounts of disease progression can occur, ranging from mild inflammatory changes to free perforation and abscess. The process that is poorly understood relates to the factors that lead to the perforation of the diverticulum. The predominant theory is based on inflammation being the main cause of perforation, although perforation can occur in the setting of no inflammation when high intraluminal pressures are present. There are many factors that most likely act in conjunction to cause the inflammation. Some of the factors implicated include obstruction of diverticulum, stasis, alteration in local bacterial microflora, and local ischemia. Symptoms still may persist after there is documented resolution of inflammation. Heightened visceral hypersensitivity may account for some of the symptoms observed. Studies have shown that colonic nerves may be damaged secondary to the inflammation, and this may lead to hyperinnervation and subsequently, persistence of symptoms.

Symptoms and staging

Pain in the left lower quadrant associated with low-grade fevers, change in bowel movements, and mild leukocytosis are the classic clinical signs and symptoms of diverticulitis. A redundant sigmoid lying in the right iliac fossa occasionally can present with right-sided pain and thus be mistaken for acute appendicitis. Associated colonic symptoms can include obstipation, diarrhea, or increased mucus production. Abdominal distension secondary to ileus, as well as nausea or vomiting, can be present. Inflammatory processes that abut the bladder can lead to urinary urgency or frequency.

A pericolonic abscess secondary to perforated diverticulitis causes localized peritonitis. Involvement of the small intestine in a phlegmon can lead to obstruction. Fistulizing diverticulitis leads to specific symptoms related the organs involved. Colovesical fistulas can present as pneumaturia, fecaluria, or recurrent urinary tract infections. Enterocolonic fistulas have the potential to lead to severe diarrhea, especially if the small bowel involved is proximal. Passing stool through the vagina is the hallmark of colovaginal fistulas, and women with previous hysterectomy are at highest risk for fistula formation to the exposed vaginal cuff.

The vast majority of patients with diverticulosis are asymptomatic and therefore do not require any further treatment. Symptomatic patients can be subclassified into four main groups ( Table 1 ). Complicated diverticulitis is defined as diverticular disease associated with obstruction, stricture, fistula, abscess, or perforation. Diverticular bleeding is usually not associated with diverticulitis and often presents as sudden and vigorous bright red lower gastrointestinal bleeding, which is usually self limiting. The Hinchey staging system has been used to differentiate severity of disease in the setting of acute diverticulitis associated with abscess ( Box 1 ).

| Symptomatic Diverticulitis | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Isolated, uncomplicated | Single episode of acute diverticulitis |

| Recurrent, uncomplicated (chronic) | Multiple, discrete episodes of acute diverticulitis |

| Complicated | Acute diverticulitis associated with abscess, fistula, obstruction, perforation, or stricture |

| Smoldering | Acute diverticulitis associated with ongoing, chronic symptoms |

Stage I

Paracolic abscess confined to mesentery of colon

Stage II

Distant abscess in pelvis or retroperitoneum

Stage III

Purulent peritonitis

Stage IV

Feculent peritonitis

Symptoms and staging

Pain in the left lower quadrant associated with low-grade fevers, change in bowel movements, and mild leukocytosis are the classic clinical signs and symptoms of diverticulitis. A redundant sigmoid lying in the right iliac fossa occasionally can present with right-sided pain and thus be mistaken for acute appendicitis. Associated colonic symptoms can include obstipation, diarrhea, or increased mucus production. Abdominal distension secondary to ileus, as well as nausea or vomiting, can be present. Inflammatory processes that abut the bladder can lead to urinary urgency or frequency.

A pericolonic abscess secondary to perforated diverticulitis causes localized peritonitis. Involvement of the small intestine in a phlegmon can lead to obstruction. Fistulizing diverticulitis leads to specific symptoms related the organs involved. Colovesical fistulas can present as pneumaturia, fecaluria, or recurrent urinary tract infections. Enterocolonic fistulas have the potential to lead to severe diarrhea, especially if the small bowel involved is proximal. Passing stool through the vagina is the hallmark of colovaginal fistulas, and women with previous hysterectomy are at highest risk for fistula formation to the exposed vaginal cuff.

The vast majority of patients with diverticulosis are asymptomatic and therefore do not require any further treatment. Symptomatic patients can be subclassified into four main groups ( Table 1 ). Complicated diverticulitis is defined as diverticular disease associated with obstruction, stricture, fistula, abscess, or perforation. Diverticular bleeding is usually not associated with diverticulitis and often presents as sudden and vigorous bright red lower gastrointestinal bleeding, which is usually self limiting. The Hinchey staging system has been used to differentiate severity of disease in the setting of acute diverticulitis associated with abscess ( Box 1 ).

| Symptomatic Diverticulitis | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Isolated, uncomplicated | Single episode of acute diverticulitis |

| Recurrent, uncomplicated (chronic) | Multiple, discrete episodes of acute diverticulitis |

| Complicated | Acute diverticulitis associated with abscess, fistula, obstruction, perforation, or stricture |

| Smoldering | Acute diverticulitis associated with ongoing, chronic symptoms |

Stage I

Paracolic abscess confined to mesentery of colon

Stage II

Distant abscess in pelvis or retroperitoneum

Stage III

Purulent peritonitis

Stage IV

Feculent peritonitis

Evaluation and workup

The workup of a patient suspected of having diverticulitis begins with thorough history taking and physical examination. It is important to try and characterize the pain and also assess for possible complications of the disease. Important history and symptoms to be elucidated include character and location of the pain, associated symptoms (fevers, chills, change in bowel habits, nausea, vomiting), and evidence of a complication (obstructive symptoms, pneumaturia, fecaluria, urinary tract infections, foul vaginal discharge). The differential diagnosis for lower abdominal pain that a practitioner should keep in mind includes appendicitis, urinary tract infection, irritable bowel syndrome, nephrolithiasis, gynecologic problems, infectious or ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancy.

Laboratory evaluation should include complete blood cell count with differential analysis and urinalysis. The goal of imaging for acute diverticulitis is to define the location of disease, the extent of inflammation, and the presence of any complications. Multiple modalities have been used and studied in this setting, including plain radiographs, contrast enema, ultrasound, and computed tomography (CT). Barium enema is the most sensitive test to diagnose diverticulosis. Although barium enema is an excellent test for defining luminal abnormalities of the colon, it does not visualize extraluminal manifestations of disease well. Contrast studies may reveal extravasation of contrast, luminal narrowing, tethering, strictures, and fistulas. In the presence of acute inflammation, only water-soluble contrast should be employed due to the risk of extravasation or perforation during the study. Barium peritonitis can be a life-threatening complication.

CT has become the imaging modality of choice for acute diverticulitis due to its sensitivity and specificity. CT can assess intraluminal and extraluminal colonic pathology, evaluate the pericolonic tissue, define involvement of adjacent organs, and rule out other pathology such as appendicitis or gynecologic abnormalities ( Fig. 2 ). Another aspect that makes CT the test of choice in assessing acute diverticulitis is that it allows for therapeutic intervention, such as percutaneous drainage of abscesses.

Cystography can be helpful to evaluate suspected colovesical fistulas, although these fistulas can be difficult to demonstrate radiographically. Even if these fistulas cannot be visualized, the presence of acute diverticulitis and air in the bladder, in the absence of urinary instrumentation, is generally diagnostic for colovesical fistula. Endoscopy is another modality that is often considered in the workup of diverticulitis. However, most experts believe that colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy is not indicated in the acute setting, as there may be an increased chance of perforation or aggravating the inflammation.

Following resolution of the acute diverticulitis episode it is vital to investigate the entire colon to rule out potential confounding diagnosis that can mimic diverticulitis, such as cancer or inflammatory bowel disease. About 3% to 5% of cases of diverticulitis are actually adenocarcinomas mimicking the symptoms of diverticular disease. In addition to colonoscopy and barium enema, the use of CT colonography has increased in screening these patients for synchronous lesions. CT colonography is equivalent to colonoscopy in identifying significant lesions in the setting of diverticular disease. In addition, colonoscopy can be difficult in patients with extensive diverticular disease, and colonography would render colonoscopy unnecessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree